Jujiro Wada (Japanese: 和田重次郎) (ca. 1872-5 March 1937) was a Japanese adventurer and entrepreneur who achieved fame for his exploits in turn-of-the-20th-century Alaska and Yukon Territory.

Early life

According to his own account, Wada was born on February 12, 1872,[1] in Ehime Prefecture, Japan, to wealthy parents. Wada said that he arrived in San Francisco in late 1891, and that his purpose of traveling to the United States was to attend Yale University.[2]

Researcher Yuji Tani provides an alternative story. According to Tani, Wada was born on January 6, 1875, in Komatsu, Ehime Prefecture. He was the second son of a former samurai fallen on hard times, and his father died when Jujiro was four. Subsequently, Jujiro and his mother went to live with his mother's relatives in what is today Matsuyama City. In 1886, when he was 13 or 14 years of age (by Japanese counting, which would mean 12 or 13 by American), Jujiro went to work at Toda-Seishi Company, which was a local paper factory. In 1890, he went to work for the Yamaya Transport Company in Mitsuhama. Meanwhile, he heard tales about the fabulous wealth of America.[3]

According to subsequent US immigration data, Wada took a steamship to San Francisco in March 1890.[4] However, according to his own account, he stowed away aboard a ship out of Kobe in 1891.[3]

Whaling

Wada was a cabin boy and cook aboard the Pacific Steam Whaling Company's bark Balaena from March 1892 until October 1894. During this time, the ship was hunting baleen whales in the North Pacific and Arctic Oceans.[5] Wada learned English during this voyage. His teacher was the ship's master, H. Havelock Norwood.[6][7]

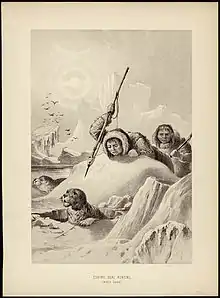

Wada returned to Alaska in 1895, this time as a shore hunter at Utqiagvik.[3] Shore hunters hunted whales using land-based boats, and also hunted caribou with which to provision visiting whale ships. Wada worked for the Cape Smythe Whaling and Trading Company. The local manager was Charles Brower.[8] This is probably when and where Wada learned to handle sled dogs and speak Alaska native languages.

In 1896, Wada returned to Japan to see his mother. He was in Japan about three months.[3]

Following his trip to Japan, Wada returned to Alaska, where he went back to working as a shore whaler at Utqiagvik.[9] In September 1897, an early freeze trapped eight ships of the U.S. whaling fleet in the ice off Point Barrow. Naturalist Edward Avery "Ned" McIlhenny (of the Tabasco sauce family) and two assistants were then living at the Point Barrow refuge station, and during the next few months, the McIlhenny party and the Barrow shore whalers helped the crews of the stranded whale ships.[10]

Prospector and cook

Wada was in San Francisco during 1898-1899,[11] and in August 1914, a young girl from San Francisco calling herself Helen Wada Silveira wrote the postmaster in Fairbanks, claiming to be Wada's daughter. She wrote a message to the Fairbanks Times and when presented to him by an acquaintance, Wada replied back, calling her "Himeko."[12] Her sixteen children and their families live throughout Northern California today.

Wada was in Nome during 1901.[11][13] He apparently spent the winter of 1901-1902 in Seattle, because on May 26, 1902, he arrived in Skagway on a steamer out of Seattle.[14]

From Skagway, Wada caught a different ship to St. Michael, and then took a gasoline launch up the Koyukuk River. In August 1902, Wada took a job as a cook for E.T. Barnette, who had established a trading post on the banks of the Chena River that subsequently became the site of modern Fairbanks.[15][16]

Fairbanks

On December 28, 1902, Wada drove one of Barnette's dog teams into Dawson City to tell the Canadians about the recent gold strikes near Fairbanks.[17] Reporter Casey Moran of the Yukon Sun subsequently wrote a front-page story whose headline screamed "Rich Strike Made in the Tanana."[14] The story caused several hundred miners to leave Dawson City for Fairbanks, where most were disappointed to find that prices were high and the best sites were already staked. An angry mob approached Barnette's store, and threatened violence against both Barnette and Wada. Nonetheless, said Wada in September 1907:[18]

The story that I was about to be hanged for causing a thought-to-be-fake stampede was not correct. The fact is that the miners held a meeting to decide as to the price of flour then being offered by one of the trading companies. They thought the price exorbitant. It was rumored that the miners had a rope on my neck, and were about to hoist me. Now that is not true. The other part of the story, that I showed a copy of the [Seattle] Post-Intelligencer saying that several years before I had rescued a party of shipwrecked whalers in the Arctic in dead of winter is true. I did show that paper to let some of the boys know I had been up North, but it was not in a plea to save my neck.

More trials

After this experience, Wada left Fairbanks for Nome, where, in July 1903, he was arrested on the charge of failing to report the sale of 40 mink pelts. He paid the fine, and left town.[19]

During the winter of 1904-1905, Wada was hunting seals along the Beaufort Sea.[20] He was accompanied by several Indians. In August 1906, he was back in Nome. He promptly lost the money he'd made selling pelts in a card game, and he was arrested yet again, this time because some of the money he'd lost belonged to his Indian companions. The two Indians testified against him, but an all-white jury acquitted him anyway.[21] Wada was arrested a third time, in Candle, on the same charges, and he spent the rest of the year in and out of court.[6]

Marathon runner

Needing money to pay his lawyers, Wada began running indoor marathon races. These were gambling events, in which prizes were measured in thousands of dollars. Wada ran well, too, winning a Nome marathon in March 1907.[22] Said the Dawson Daily News on May 6, 1908:

All the Japanese boys in town had wagered their last cent of money on their fellow countryman, and their confidence in their man was never lost. Wada was the surprise of the race. Many people believed that he would make a strong showing, but only a few had given the dark-skinned boy credit for the wonderful powers of endurance which he displayed ... During the entire race he was off the track but once -- and for only six minutes, the actual time consumed in changing his shoes. While on the run he ate a little raw egg and some tomato, drank a little mineral water, and that was all.

In August 1907, Wada took his money to Vancouver, British Columbia. The Vancouver Daily Province of August 7, 1907 reported that Wada was a fine storyteller, a favorite being the one about the time he trained two polar bear cubs to pull his sled.

After a month in Vancouver, Wada returned to Dawson City. He secured a dog team, and then drove to Rampart, Alaska, to do some prospecting.[23] He visited whalers wintering at Herschel Island on March 15, 1908.[24] He left the whalers on March 21, and returned to Dawson City via Rampart House, Yukon Territory. It was on this trip that Wada, running short of dog food, reportedly fed the animals his sealskin pants. "Fortunately," he said, "the spring days were so warm that I did not suffer so keenly as such a sacrifice would have entailed in winter."[23] Then, after filing some mining claims and buying a new worsted suit and brown derby, Wada caught a series of steamers to Nome.[25]

Wada left Nome on December 18, 1908, and arrived in Fairbanks on January 11, 1909. This meant his sustained rate by dog team was about 35 miles per day. The reason for this haste was an indoor marathon scheduled for January 15, 1909. Wada finished second.[26]

Wada signed up to run in Fairbanks' Independence Day Marathon, which was scheduled for July 1, 1909, but he fell ill and so didn't participate.[27][28] After recovering, Wada went south, to run in more long-distance races. On October 7, 1909, he ran a 20-mile race in Vancouver, British Columbia. He lost.[29] He was scheduled to run an officially sanctioned marathon in Seattle on October 17, but did not. The winner, Henri St. Yves, set a world record in that race (2 hours, 32 minutes, 9 and 1/5 seconds).[30]

Establishing the Iditarod Trail

.jpg.webp)

Wada left Seattle on November 24, 1909. The Seattle Times published later that day recorded his departure. Said the newspaper article:

Clad in a suit of blue serge with white starched collar, Jayerio [sic] Wada, a well known Japanese Alaskan musher, who left for Seward on the Yucatan, of the Alaska Steamship Company, this morning, resembled an agent for an Oriental firm rather than a veteran adventurer ... Wada, as he ran up the gang plank, was recognized by several Alaskans, who were on the pier to witness the sailing of the steamship, he turned and said: 'Good luck everybody. Follow me and you all will have money.'

After arriving in Seward, Wada and Alfred Lowell, Dick Butler, and Frank Cotter helped pioneer the Iditarod Trail.[31] After finishing this project, Wada returned to Seattle. From Seattle, he went to Louisiana, where he visited Edward McIlhenny, probably to raise money for further expeditions.[27] He returned to Alaska via Seattle in April 1911.[32]

In early 1912, Wada was in the Kuskokwim area, looking for traces of a Japanese man known locally as Allen, who had disappeared there. On March 11, 1912, Wada was in Iditarod.[33] In July 1912, he and his partner, John Baird, made a gold strike on the Tulasak River.[34] Wada took about $12,000 in gold with him when he went to Seattle to report the findings to his backers, who included McIlhenny and the Guggenheim brothers.[35]

Wada returned to Seward in November 1912. He brought with him two sled loads of mining equipment, another sled load of miscellaneous supplies, and four Japanese companions who would serve as assistant dog drivers.[36] The Japanese and their twenty dogs then drove to the Bear Creek strike. Wada remained at the Bear Creek site until February 1913.[37]

Late life

Wada went to Seattle for a short while, then he returned to Alaska in May 1913.[38] That same year, he was described in John Underwood's Alaska, an Empire in the Making, as one of Alaska's best long-distance dog sled drivers.[39]

In 1915, a man named Ernest Blue wrote in the Cordova Daily Times that Wada was a Japanese spy asserting that Blue had seen cash and a map of Alaska in Wada's possession.[3] This story reappeared in 1923 and during WWII.[40] During May 1915, Wada was in San Pedro, California, working at Van Camp's tuna packing plant, but left town swiftly after receiving a phone call. As with many stories about Wada, the published accounts are contradictory. In the Seattle Times on May 15, 1916, Wada insisted the phone call was a job offer in Alaska, and he traveled to New York. However, on page 217 of Tani, 1995, Wada wrote a letter to his friend Sunada, written on Van Camp Sea Food Company stationery. that reads, "Sorry to say but I am compelled to leave here ... otherwise they will kill me."[41]

During 1917-1918, Wada resumed prospecting in the Yukon, mostly along High Cache Creek. In 1919, he went to the Northwest Territories.

On September 6, 1920, he entered New York State via Niagara Falls. He listed his last residence as Herschel Island, Northwest Territories, and his employer as E.F. Lufkin. He listed his height as 5'2", his hair as black, and his complexion as dark.[42]

From 1920-1923, he was trapping foxes on the Upper Porcupine. He also searched for gold around Herschel Island and for oil around Fort Norman (modern Norman Wells).[43] His business partners during this time included the veteran trader Poole Field.[44][45][46][47]

Wada left Canada in April 1923.[48] On May 3, 1923, he arrived at Ketchikan aboard the SS Princess Mary. He listed himself as a citizen of Canada, but was not allowed entry into Alaska because he had no passport.[49]

His subsequent whereabouts are not currently documented, but in 1930, he was in Chicago, Illinois. In May 1934, he was in Seattle, having recently arrived from San Francisco. During January 1936, he was in Green River, Wyoming. During the winter of 1936-1937, he was in Redding, California.[50]

He died at the San Diego County hospital on March 5, 1937. The cause of death was listed as peritonitis caused by diverticulitis.[1]

Wada was buried at county expense, probably in the city-owned Mount Hope cemetery. But he was not forgotten, at least not in Alaska and the Yukon, and in 2007, a Yukon Quest sled dog race was dedicated to his memory.[51]

References

- 1 2 County of San Diego--Standard Certificate of Death #37-023109, filed March 11, 1937.

- ↑ Cotter, Frank. "Ju Wada As I Knew Him," Japanese-American Courier, July 3, 1937, p 2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Miyahara, Fumiko. "The tale of the Yukon's dog-mushing Samurai," Yukon News, March 13, 1996, 14, summarizing the Japanese-language Orora ni kakeru samurai (Samurai Who Ran to the Northern Lights) by Yuji Tani. Japan: Yama to Keikoku, 1995; Ronald Inouye, "Jujiro Wada: musher, long distance runner, and Fairbanks co-founder?" Fairbanks News-Miner, September 13, 2009, http://newsminer.com/news/2009/sep/13/jujiro-wada-musher-long-distance-runner-and-fairba/%5B%5D

- ↑ Ancestry.com. Border Crossings: From Canada to U.S., 1895-1956 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: The Generations Network, Inc., 2007. Arrival date September 6, 1920, age 46, born about 1874, in Iyo, Japan.

- ↑ Dates of service are from John R. Bockstoce, Steam Whaling in the Western Arctic. New Bedford, Massachusetts: Old Dartmouth Historical Society, 1977, p. 114.

- 1 2 DeArmond, Robert N. "This is My Country," Alaska Magazine, March 1988, pp. 37-38.

- ↑ A photo of Wada in Dawson City appears on a site dedicated to H. H. Norwood.

- ↑ Brower, Charles D. Fifty Years Below Zero: A Lifetime of Adventure in the Far North. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press, 1994.

- ↑ Dawson Daily News, October 18, 1909; Dawson Daily News, January 11, 1913; Seattle Times, May 9, 1916. Wada's accounts of his participation appear in Seattle Times, September 18, 1909, and Dawson Daily News, September 22, 1909.

- ↑ Bockstoce, John. "The Arctic Whaling Disaster of 1897," Arctic Whaling, 1977, pp. 27-42.

- 1 2 Kagan, Norm. "Wada the Wanderer." Archived 2013-02-22 at archive.today

- ↑ Dawson Daily News, September 5, 1914; Fairbanks Times, August 5, 1914.

- ↑ Seattle Post-Intelligencer, July 21, 1912.

- 1 2 Yukon Sun, January 17, 1903.

- ↑ Cole, Terrence. E.T. Barnette: The Strange Man Who Founded Fairbanks. Anchorage, Alaska: Northwest Publishing Co., 1981.

- ↑ Hedrick, Basil & Savage, Susan. "Steamboats on the Chena: The Founding & Development of Fairbanks, Alaska." Epicenter Press, Inc., 1988.

- ↑ A photo of Barnette's dog team appears on page 217 of E. Tappan Adney, The Klondike Stampede, Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1994. The rig shows five dogs in a row, but a photo of the fan harness that Wada often used appears on pages 219-220.

- ↑ Dawson Daily News, September 28, 1907.

- ↑ Seattle Times, July 27, 1903.

- ↑ Yukon Daily News, September 22, 1909.

- ↑ Dawson Daily News, December 10, 1906.

- ↑ Hunt, William R. North of 53 Degrees: The Wild Days of the Alaska-Yukon Mining Frontier. New York: Macmillan, 1974, 163.

- 1 2 Dawson Daily News, April 27, 1908.

- ↑ Dawson Daily News, April 28, 1908.

- ↑ Dawson Daily News, April 29, 1908; Seattle Post-Intelligencer, July 5, 1908.

- ↑ Dawson Daily News, February 2, 1909; Seward Weekly Gateway, January 30, 1909; Yukon World, January 30, 1909.

- 1 2 Dawson Daily News, July 8, 1912

- ↑ Seattle Times, August 19, 1909.

- ↑ Seattle Times, October 8, 1909.

- ↑ Seattle Times, October 18, 1909.

- ↑ Seward Weekly Gateway, December 4, 1909; Seward Weekly Gateway, January 15, 1910; Seward Weekly Gateway, February 5, 1910; Frank Cotter, Japanese-American Courier, July 17, 1937.

- ↑ Seattle Times, April 11, 1911; Seattle Times, July 12, 1912.

- ↑ Fairbanks Daily Times, March 12, 1912.

- ↑ Fairbanks Daily Times, June 15, 1912; Seattle Post-Intelligencer, July 21, 1912.

- ↑ Seattle Times, October 30, 1912; Letter of Agreement between Jujiro Wada and E.A. McIlhenny dated September 14, 1912, in McIlhenny Company Archives; Mary J. Barry. Seward, Alaska: A History of the Gateway City, Part I: Prehistory to 1914. Anchorage, Alaska: Self-published, 1987.

- ↑ Seattle Times, November 23, 1912; Dawson Daily News, January 11, 1913.

- ↑ Fairbanks Daily Times, February 18, 1913.

- ↑ Seattle Times, May 2, 1913.

- ↑ Underwood, John Jasper. Alaska, an Empire in the Making. New York: Dodd, Mead, and Co., 1913, pp. 320-321.

- ↑ "How the Japs Spied on Alaska 50 Years Ago," The American Weekly, date unknown but circa 1943.

- ↑ Tani, Yuji. Samurai Who Ran to the Northern Lights. Japan: Yama to Keikoku, 1995.

- ↑ Ancestry.com. Border Crossings: From Canada to U.S., 1895-1956 (database on-line). Provo, UT, USA: The Generations Network, Inc., 2007.

- ↑ Newport, Rhode Island, Mercury, December 17, 1921.

- ↑ Daniel, Hawthorne. "The Canadian Oil Rush, Limited," World's Work, 43, December 1921; Winnipeg Evening Tribune, March 22, 1922.

- ↑ Northwest Territories Archives Archived 2011-05-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Struzik, Ed. Ten Rivers: Adventure Stories from the Arctic. Winnipeg, Manitoba: CanWest Books, 2005, p. 23.

- ↑ Film of Poole Field Archived 2007-07-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Dawson Daily News, May 17, 1923.

- ↑ Ancestry.com. Alaska Alien Arrivals, 1906-1949 (database on-line). Provo, UT, USA: The Generations Network, Inc., 2006. Original data: Alaska. Alphabetical Index of Alien Arrivals at Eagle, Hyder, Ketchikan, Nome, and Skagway, Alaska, June 1906-August 1946. Washington, D.C.: National Archives. Micropublication M2016. 1 roll.

- ↑ Svinth, Joseph R. "Tall Tales and True Stories: Ju Wada, Sourdough," unpublished paper read for the Alaska Historical Society, September 2002.

- ↑ "Yukon Quest - East Meets West at the Yukon Quest." January 25, 2007 Archived September 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine