Joseph Agricol Viala | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 22 February 1778 Avignon, Papal States (modern France) |

| Died | 8 July 1793 (aged 15) Caumont-sur-Durance, Vaucluse, France |

| Allegiance | First French Republic |

| Service/ | Army |

Joseph Agricol Viala (22 February 1778 – 6 July 1793) was a child hero in the French Revolutionary Army. He was killed at age 15, though he is most often portrayed as a younger child of 11–13.[1]

Life

Viala was living in Avignon when, in 1793, a federalist revolt broke out in the Midi after the fall of the Girondins in Paris. Supported by the British, the French Royalists allied themselves with the Federalists and took control of Toulon and Marseille. Faced with this uprising, the Revolutionary soldiers were forced to abandon Nîmes, Aix and Arles to the insurgents and fall back on Avignon. The inhabitants of Lambesc and Tarascon joined up with the rebels from Marseilles and together they headed for the Durance in order to march on Lyon, which had also revolted against the central government in Paris. The rebels hoped to destroy the Convention and put an end to the French Revolution.

Joseph Agricol Viala was a nephew of Agricol Moureau, a Jacobin from Avignon, editor of the Courrier d'Avignon and administrator of the département of Vaucluse. Joseph Agricol thus became commander of the "Espérance de la Patrie", a National Guard formed wholly of young men from Avignon.[2]

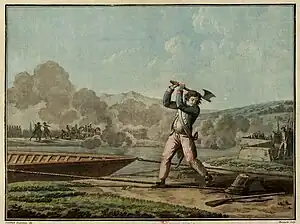

On hearing news of the approach of the rebels from Marseille, at the start of July 1793, the Republican forces (mainly those from Avignon) gathered to stop the rebels crossing the Durance. Viala attached himself to the national guards from Avignon. Numerically inferior, their only solution was to cut the ropes of the bac de Bonpas under enemy fire. To do so, they had to cross a road completely exposed to rebel fire and behind which the Revolutionary forces had dug in. Despite its necessity, the Revolutionary forces were reluctant to undertake such a hazardous mission. According to accounts of the event, the 12-year-old Viala grabbed a hatchet, launched himself at the cable and started to cut it. He was the subject of several musket volleys and he was mortally wounded by a musket ball from one of them. One account stated:

In vain they tried to hold him back ; he braved the danger and no one could stop him from carrying out his audacious plan. He seized a sapper's hatchet, he shot at the enemy several times with his musket, then, despite the musket balls whistling around him he reached the river bank and, seizing his hatchet, struck the rope with vigour. Luck seemed to be with him at first; he nearly completed his perilous task without being hit, when at that moment a musket ball pierced his breast. He still managed to get up ; but he fell again with great force, crying out [in Provencal dialect] "M’an pas manqua ! Aquo es egaou ; more per la libertat." ("They haven't missed me! All is equal - I die for liberty."). Then he expired after the sublime farewell, without a complaint or regret.[3]

Viala's attempt was unable to stop the rebels crossing the Durance, however. Nevertheless, it allowed the Revolutionary forces to carry out an ordered retreat without being able to pick up Viala's body. According to tradition, the Revolutionary soldier who heard Viala's last words tried to pick up the body but had to retreat before he could do so. This left the body to be insulted and mutilated by the advancing Royalists before they crossed the river. Learning of her son's death, Viala's mother said "Yes [...] he died for the fatherland!".

Honours

18th century

Viala and Bara were the best known child heroes of the French Revolution, though Viala was later and thus less well-known - indeed, the Jacobin press did not invoke his memory before pluviôse an II. It was above all the speech made by Robespierre before the Convention on 18 floréal which contributed to the spread of Viala's mythology. In that speech, Robespierre stated "By what fate or by what ingratitude has one yet hero younger and worthier of posterity been left forgotten?". At the request of Barère, the assembly voted that Viala be honoured in the Panthéon, though the ceremony had to be postponed from 30 messidor to 10 thermidor and was then cancelled on Robespierre's fall on 9 Thermidor. Even so, during the month of prairial, Payan published a Précis historique sur Agricol Viala which contributed to Viala's rising popularity. A civic festival was organised in Avignon on 30 messidor "in honour of Bara and Viala".[2] An engraving of Viala's face was also distributed to all primary schools.

The engraver Pierre-Michel Alix (1762–1817) produced a head-and-shoulders portrait of Viala. Louis Emmanuel Jadin (1768–1853) wrote the one-act play Agricol Viala, ou Le jeune héros de la Durance (Agricol Viala, or The young hero of the Durance), put on in Paris on 1 July 1794. 1794 also saw the composition of the marching song the Chant du départ, whose fourth stanza is placed in a child's mouth and mentions both Bara and Viala. The 1795-launched ship Viala was named after him.

19th and 20th centuries

In 1822, the sculptor Antoine Allier created a life-size bronze monument to Viala, showing him nude and from behind, with his right hand placed on a hatchet and his left arm gripping a pole with a ring and a length of rope. After being given by the Louvre to the town museum, it was set up on place Gustave-Charpentier, in the suburb of Boulogne-sur-Mer, in June 1993.

Under the French Third Republic, histography and scholarly literature contributed to renewed interest in the figures of Viala and Bara.[2] Viala is also one of the 660 figures whose names are engraved on the Arc de triomphe (he appears on the 18th column as VIALA) and the rue Viala, in the 15e arrondissement of Paris, bears his name.[4]

Controversies

In the historiographical struggle between pro- and anti-Revolutionary figures, local anti-Revolutionary historians have tried to establish that Viala provoked the rebels with rude gestures. Other than Viala, it seems above all to have been his uncle (known as the "homme rouge" or "red man") who had been seen doing this.[2]

References

- ↑ Perna, Antonia (2021). "Bara and Viala, or Virtue Rewarded: The Memorialization of Two Child Martyrs of the French Revolution". French History. 35 (2): 192–218. doi:10.1093/fh/craa071.

- 1 2 3 4 Vovelle, Michel (2005). "Viala, Agricol Joseph". In Soboul, Albert (ed.). Dictionnaire historique de la Révolution française (in French). Paris: Quadrige. p. 1087.

- ↑ Mullié, Charles, ed. (1852). "Joseph Agricol Viala". Biographie des célébrités militaires des armées de terre et de mer de 1789 à 1850 (in French). Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- ↑ "rue Viala". paris.fr (in French). 9 June 2008. Archived from the original on January 7, 2013. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

External links

![]() Media related to Joseph Agricol Viala at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Joseph Agricol Viala at Wikimedia Commons