John Montresor | |

|---|---|

A portrait of John Montresor, by John Singleton Copley, circa 1771 | |

| Born | 22 April 1736 Gibraltar |

| Died | June 1799 (aged 63) Maidstone, Kent, England |

| Allegiance | Kingdom of Great Britain |

| Service/ | Corps of Engineers |

| Rank | Captain |

| Unit | 48th Regiment of Foot |

| Battles/wars | |

| Relations | James Gabriel Montresor (father) Susanna Haswell Rowson (cousin) Robert Haswell (cousin) Henry Montresor (son) |

Captain John Montresor (22 April 1736 – June 1799) was a British military engineer and cartographer in North America.

Early life

Born in Gibraltar on 22 April 1736 to the British military engineer James Gabriel Montresor and his first wife, Mary Haswell, John Montresor spent his early life there (and presumably on Menorca, where his father was briefly stationed). He was in England between 1746 and 1750 and attended Westminster School. He learned the principles of engineering from his father and in his later teens served as assistant engineer to his father at Gibraltar.

French and Indian Wars

In 1754, he accompanied his father to America and served as an ensign in the 48th Regiment of Foot on the expedition to Fort Duquesne, also performing as a supernumerary engineer. In the defeat that followed, he was wounded but survived to learn of his promotion to lieutenant days before the battle. He remained in America, serving along the Mohawk River and at Fort Edward abd then accompanying British forces to Halifax. In 1758, he was commissioned a practicing engineer in the Corps of Engineers, and as such was present at the siege of Louisbourg, and later, at that of Quebec, there drawing one of the last known portraits of General Wolfe, who died in the deciding battle.

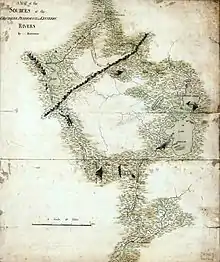

With the defeat of the French, Montresor was sent to neighbouring villages and as far afield as Cape Breton, using the language of his Huguenot ancestors to elicit oaths of allegiance. He was also twice sent overland from Quebec to Boston with dispatches, on one of these journeys, in a mid-winter blizzard, being reduced to eating belt and shoe leather in order to avoid starvation. He also, during this period, performed various surveys and prepared maps of Acadia, the Saint Lawrence River, and of his route along the Kennebec River. (The journal of this last expedition through the wilds of Maine would fall into enemy hands in the American Revolution, and was used as a guide by Benedict Arnold in his expedition against Quebec.)

During Pontiac's Rebellion, he carried dispatches and led troops to besieged Fort Detroit. He designed and built fortifications on the Niagara River at Fort Niagara and Fort Erie as well as a series of blockhouses and an early gravity railroad along the Niagara Portage between 1762 and 1764.

Montresor's journal of 1764 contains the first written reference to 'Buffalo Creek',[1] from which Buffalo, New York, derives its name.

Revolutionary-era America

Stationed at Fort George (the former site of Fort William Henry) in 1765, he witnessed rioting in Albany and New York City in response to the Stamp Act, and in the same year was promoted to captain lieutenant, and engineer extraordinary, as well as barrackmaster for ordnance in North America. Over the next several years, he surveyed the boundary between New York and New Jersey, and he repaired or constructed barracks and fortifications in Boston, New York City, the Bahamas, and Philadelphia, where he would build a fortification on Mud Island. In 1772, he was elected a member of the American Philosophical Society.[2] During this period, he also took a six-month leave in England and spent time on Bermuda. He also purchased an island in New York Harbor which would be called Montresor's Island (now Randall's Island).

He was in Boston at the outset of the American Revolutionary War and marched with Percy to relieve the British troops returning from Concord. He was appointed chief engineer in America and captain in late 1775. He was present at the Battle of Long Island the next year, and was present at the execution of Nathan Hale on 22 September 1776. It is said that he kindly sheltered Hale in his office, giving him pen and paper to write final letters to his family, and that the execution moved him deeply. He was sent to the rebel lines under flag of truce to report the event and conveyed Hale's last words to William Hull. Having been superseded as chief engineer, he was placed as aide-de-camp on the staff of General William Howe but was later reinstated as chief engineer. On 13 January 1777, his home on Montresor's Island was burned.

In 1777, he was involved in the military campaigns in New Jersey, and present at the action at Quibbleton. He also participated at Brandywine later that year, and accompanied the army to Philadelphia where he launched the attack that destroyed his own Mud Island defences. He directed the construction of new defences for the city, including the first pontoon bridge at Gray's Ferry on the Schuylkill River. Along with John André, he was one of the planners of the lavish ball, the Mischianza, given in Philadelphia in honor of General Howe.

Again superseded in his role as chief engineer, he returned to England and in March 1779 resigned from the army, bringing to an end over two decades of American service, all reported in journals (although many of these were lost).

Retirement and death

In England, he was called before Parliament to testify on the conduct of the war and on several occasions was required to support his expenditures during his various campaigns (for which he is said to have been imprisoned at one point). He purchased an estate at Belmont, Kent, had a residence at Portland Place, London, and he served as director of the French Hospital. He toured Europe in 1785 and 1786, visiting France, Germany and Switzerland. In his later years, his accounts came under scrutiny, and much of his property was seized by the state to recover disallowed expenses. He died in Maidstone Prison, where he was incarcerated, apparently in connection with his outstanding debts, in June 1799.[3]

Family

Montresor's romantic life has been the subject of much writing. He married at New York 1 March 1764, Frances Tucker, who was born in New York, 23 April 1744, daughter of Thomas Tucker of Bermuda, stepdaughter of Reverend Samuel Auchmuty and half-sister of General Sir Samuel Auchmuty. She returned to England with her husband, and survived him, dying 28 June 1828, at Rose Hill, Kent. By her, he had, with others, General Sir Henry Tucker Montresor, General Sir Thomas Gage Montresor, and Mary Lucy Montresor, who became the first wife of General Sir Frederick William Mulcaster (half-brother of Capt Sir William Howe Mulcaster).

In addition to these relationships, he also had other more irregular connections. A surviving letter from Detroit in 1763 mentions the death of an apparent mistress, "poor Nancy", and that he had been "on the Common" since. Likewise, he made a small grant for the support of the child of the daughter of a local English farmer, of which John was the father.

Finally, his name appears broadly as the father of Frances, the second wife of Ethan Allen. Born to a Mohawk Valley woman on, Ethan Allen would later record, 4 April 1760. After Frances's mother died, she was adopted by her maternal aunt, Margaret, and her husband, Crean Brush, one-time secretary of the Assembly of the Colony of New York. As to her paternity, when her daughter Frances "Fanny" Allen entered Hôtel-Dieu in 1808, her mother's maiden name was recorded as Montresor. Her tombstone names her Montezuma, while an 1858 history written using family information calls her Frances Montuzan, relating that her father was a British colonel killed in the French and Indian War. Popular opinion makes John Montresor the father of Frances due in no small part to his role in a popular best-selling novel of the time.

Fiction

John Montresor has gained a certain notoriety beyond his historical role due to the writings of his first-cousin Susanna Haswell Rowson. One of the main characters in her popular novel Charlotte Temple, John Montraville, was based, at least in part, on Montresor. In the sequel, Lucy Temple, Charlotte's Daughter, Montraville is even said to have lived at Portland Place, once Montresor's residence. In the original novel, Montraville seduces the title character, an innocent English schoolgirl, and induces her to run away to America. He then abandons her, destitute and pregnant, to die in childbirth. Some authors have taken this to be a verbatim account of an event in Montresor's life with only the name changed (the author subtitles the work, "A Tale of Truth"), but others see in it a fictionalized account of the circumstances surrounding the birth of the future Frances Allen. However, the tale also bears strong similarity to one told of General John Burgoyne, and it seems likely that the author had broader inspiration for her tale.

References

- ↑ Severance, Frank H. (1902). "The Achievements of Captain John Montresor". In Buffalo Historical Society (ed.). Buffalo Historical Society Publications. Buffalo, NY: Bigelow Brothers. p. 15. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ↑ "APS Member History".

- ↑ Court documents relating to his trial can be found at the Public Records Office, Kew Gardens, London.

General

- Finigan, H.: "Montresor Papers on microfilm" David Library of the American Revolution, Washington's Crossing, PA

- Skull, G. D., The Montresor Journals, Collections of the New York Historical Society for the Year 1881.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1894). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 38. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 328–329.

- "John Montrésor" Dictionary of American Biography XIII, 101–102.

- Montrésor, Frank Montrésor, "Memoirs of the Montresors", mss. 1941, Library of Congress.

- Montrésor, F. M., "Captain John Montrésor in Canada", Canadian Historical Review, vol. 5 (1924), pp. 336–340.

- Montresor pedigree, Proceedings of the Huguenot Society of London, 1917, facing p. 293, along with "Notes and Jottings in connection with the Montresor Pedigree", ibid, pp. 293–300.

Family and fiction

- Montresor, F. M., "Who was Ethan Allen's wife?", New York Historical and Biographical Record, vol. 75 (1944), pp. 29–30.

- Buehner, Terry L., Green Mountain Women, thesis, University of Vermont, 1992, pp. 113–139.

- Hall, Benjamin H., History of Eastern Vermont, (New York: Appleton & Co) 1858, pp. 604.

- Parker, Patricia L., Susanna Rowson, (Boston: Twayne) 1986