.jpg.webp) Charles de Gaulle in 1961 | |

| Presidency of Charles de Gaulle 8 January 1959 – 28 April 1969 | |

| Party | |

|---|---|

| Election | |

| Seat | Élysée Palace |

|

| |

Charles de Gaulle's tenure as the 18th president of France officially began on 8 January 1959. In 1958, during the Algerian War, he came out of retirement and was appointed President of the Council of Ministers (Prime Minister) by President René Coty. He rewrote the Constitution of France and founded the Fifth Republic after approval by referendum. He was elected president later that year, a position to which he was re-elected in 1965 and held until his resignation on 28 April 1969.

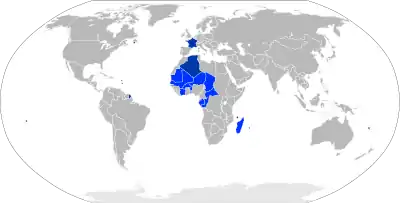

When the war in Algeria threatened to bring the unstable Fourth Republic to collapse, the National Assembly brought him back to power during the May 1958 crisis. He founded the Fifth Republic with a strong presidency, and he was elected to continue in that role. He managed to keep France together while taking steps to end the war, much to the anger of the Pieds-Noirs (ethnic Europeans born in Algeria) and the armed forces. He granted independence to Algeria and acted progressively towards other French colonies. In the context of the Cold War, de Gaulle initiated his "politics of grandeur", asserting that France as a major power should not rely on other countries, such as the United States, for its national security and prosperity. To this end, he pursued a policy of "national independence" which led him to withdraw from NATO's integrated military command and to launch an independent nuclear strike force that made France the world's fourth nuclear power. He restored cordial Franco-German relations to create a European counterweight between the Anglo-American and Soviet spheres of influence through the signing of the Élysée Treaty on 22 January 1963.

De Gaulle opposed any development of a supranational Europe, favouring Europe as a continent of sovereign nations. De Gaulle openly criticised the United States intervention in Vietnam. In his later years, his support for the slogan "Vive le Québec libre" and his two vetoes of Britain's entry into the European Economic Community generated considerable controversy in both North America and Europe. Although reelected to the presidency in 1965, he faced widespread protests by students and workers in May 1968, but had the Army's support and won an election with an increased majority in the National Assembly. De Gaulle resigned in 1969 after losing a referendum in which he proposed more decentralisation.

Founding of the Fifth Republic

The French Fourth Republic had suffered from a lack of political consensus, a weak executive, and governments forming and falling in quick succession since 1946. With no party or coalition able to sustain a parliamentary majority, prime ministers found themselves unable to risk their political position with unpopular reforms.[1] The republic began to collapse during the Algerian War, and especially after the May 1958 crisis, wherein elements of the French Armed Forces staged a coup d'état in French Algeria and demanded that Charles de Gaulle return to power, leading to fears that France as a whole would descend into civil war.[2][3]: 383–389 President René Coty publicly asked de Gaulle to help reform France's institutions.[3]: 396 De Gaulle accepted, under the precondition that a new constitution would be introduced to create a powerful presidency in which a sole executive, the first of which was to be himself, ruled for seven-year periods. Another condition was that he be granted extraordinary powers for a period of six months. De Gaulle's newly formed cabinet was approved by the National Assembly on 1 June 1958, by 329 votes against 224, while he was granted the power to govern by ordinances for a six-month period, as well as the task to draft a new Constitution.[4]

1958 indirect French presidential election

In the November 1958 legislative election, Charles de Gaulle and his supporters won a comfortable majority. On 21 December, he was elected President of France by the electoral college with 78% of the vote; he was inaugurated in January 1959. As head of state, he also became, ex officio, the Co-Prince of Andorra.[5]

Algerian War

Upon becoming president, de Gaulle was faced with the urgent task of finding a way to bring to an end the bloody and divisive war in Algeria.[6] His intentions were obscure. He had immediately visited Algeria and declared, Je vous ai compris—'I have understood you', and each competing interest had wished to believe it was them that he had understood. The settlers assumed he supported them and would be stunned when he did not. In Paris, the left wanted independence for Algeria. Although the military's near coup had contributed to his return to power, de Gaulle soon ordered all officers to quit the rebellious Committees of Public Safety. Such actions greatly angered the pieds-noirs and their military supporters.[7]

He faced uprisings in Algeria by the pied-noirs and the French armed forces. On assuming the prime minister role in June 1958, he immediately went to Algeria, and neutralised the army there, with its 600,000 soldiers. The Algiers Committee of Public Safety was loud in its demands on behalf of the settlers, but de Gaulle made more visits and sidestepped them. For the long term he devised a plan to modernize Algeria's traditional economy, deescalated the war, and offered Algeria self-determination in 1959. A pied-noir revolt in 1960 failed, and another attempted coup failed in April 1961. French voters approved his course in a 1961 referendum on Algerian self-determination. De Gaulle arranged a cease-fire in Algeria with the March 1962 Evian Accords, legitimated by another referendum a month later. It gave victory to the FLN, which came to power and declared independence. The long crisis was over.[8]

Although the Algerian issue was settled, Prime Minister Michel Debré resigned over the final settlement and was replaced with Georges Pompidou on 14 April 1962. France recognised Algerian independence on 3 July 1962, and a blanket amnesty law was belatedly voted in 1968, covering all crimes committed by the French army during the war. In just a few months in 1962, 900,000 Pied-Noirs left the country. After 5 July, the exodus accelerated in the wake of the French deaths during the Oran massacre of 1962.

With the conclusion of the Algerian War, de Gaulle was now able to seek his two main objectives: the reform and development of the French economy, and the promotion of an independent foreign policy and a strong presence on the international stage. This was named by foreign observers the "politics of grandeur" (politique de grandeur).[9]

Assassination attempts

De Gaulle was targeted for death by the Organisation armée secrète (OAS), in retaliation for his Algerian initiatives. Several assassination attempts were made on him; the most famous occurred on 22 August 1962, when he and his wife narrowly escaped from an organized machine gun ambush on their Citroën DS limousine. De Gaulle commented "Ils tirent comme des cochons" ("They shoot like pigs").[10] The attack was arranged by Colonel Jean-Marie Bastien-Thiry at Petit-Clamart.[11]: 381 Bastien-Thiry was later executed by firing squad on 11 March 1963, the last execution done by this method in France.[12]

It is claimed that there were at least 30 assassination attempts against de Gaulle throughout his lifetime.[13][14][15]

Economic policy

In the immediate post-war years France was in poor shape; wages remained at around half prewar levels, the winter of 1946–1947 did extensive damage to crops, leading to a reduction in the bread ration, hunger and disease remained rife and the black market continued to flourish.[16] After 1948, things began to improve dramatically with the introduction of Marshall Aid—large scale American financial assistance given to help rebuild European economies and infrastructure. This laid the foundations of a meticulously planned program of investments in energy, transport and heavy industry, overseen by the government of Prime Minister Georges Pompidou.

De Gaulle oversaw tough economic measures to revitalise the country, including the issuing of a new franc (worth 100 old francs).[17] Less than a year after taking office, he was confronted with national tragedy, after the Malpasset Dam in Var collapsed in early December, killing over 400 in floods. Internationally, he rebuffed both the United States and the Soviet Union, pushing for an independent France with its own nuclear weapons and strongly encouraged a "Free Europe", believing that a confederation of all European nations would restore the past glories of the great European empires.[11]: 411, 428

Aided by these projects, the French economy recorded growth rates unrivalled since the 19th century. In 1964, for the first time in nearly 100 years[18] France's GDP overtook that of the United Kingdom for a time. This period is still remembered in France with some nostalgia as the peak of the Trente Glorieuses ("Thirty Glorious Years" of economic growth between 1945 and 1974).[19]

In 1967, de Gaulle decreed a law that obliged all firms over certain sizes to distribute a small portion of their profits to their employees. By 1974, as a result of this measure, French employees received an average of 700 francs per head, equivalent to 3.2% of their salary.[20]

Nuclear weapons programme

As early as April 1954 while out of power, de Gaulle argued that France must have its own nuclear arsenal as nuclear weapons were seen as a national status symbol and a way of maintaining international prestige with a place at the 'top table' of the United Nations. Full-scale research began again in late 1954 when Prime Minister Pierre Mendès France authorized a plan to develop the atomic bomb; large deposits of uranium had been discovered near Limoges in central France, providing the researchers with an unrestricted supply of nuclear fuel. France's independent Force de Frappe (strike force) came into being soon after de Gaulle's election with his authorization for the first nuclear test.

With the cancellation of Blue Streak, the US agreed to supply Britain with its Skybolt and later Polaris weapons systems, and in 1958, the two nations signed the Mutual Defence Agreement forging close links which have seen the US and UK cooperate on nuclear security matters ever since. Although at the time it was still a full member of NATO, France proceeded to develop its own independent nuclear technologies—this would enable it to become a partner in any reprisals and would give it a voice in matters of atomic control.[21]

After six years of effort, on 13 February 1960, France became the world's fourth nuclear power when a high-powered nuclear device was exploded in the Sahara some 700 miles south-south-west of Algiers.[22] In August 1963, France decided against signing the Partial Test Ban Treaty designed to slow the arms race because it would have prohibited it from testing nuclear weapons above ground. France continued to carry out tests at the Algerian site until 1966, under an agreement with the newly independent Algeria. France's testing program then moved to the Mururoa and Fangataufa Atolls in the South Pacific.

In November 1967, an article by the French Chief of the General Staff (but inspired by de Gaulle) in the Revue de la Défense Nationale caused international consternation. It was stated that the French nuclear force should be capable of firing "in all directions"—thus including even America as a potential target. This surprising statement was intended as a declaration of French national independence and was in retaliation to a warning issued long ago by Dean Rusk that US missiles would be aimed at France if it attempted to employ atomic weapons outside an agreed plan. However, criticism of de Gaulle was growing over his tendency to act alone with little regard for the views of others.[23] In August, concern over de Gaulle's policies had been voiced by Valéry Giscard d'Estaing when he queried 'the solitary exercise of power'.[24]

Direct elections

In September 1962, de Gaulle sought a constitutional amendment to allow the president to be directly elected by the people and issued another referendum to this end. After a motion of censure voted by the parliament on 4 October 1962, de Gaulle dissolved the National Assembly and held new elections. Although the left progressed, the Gaullists won an increased majority—this despite opposition from the Christian democratic Popular Republican Movement (MRP) and the National Centre of Independents and Peasants (CNIP) who criticised de Gaulle's euroscepticism and presidentialism.[25][26]

De Gaulle's proposal to change the election procedure for the French presidency was approved at the referendum on 28 October 1962 by more than three-fifths of voters despite a broad "coalition of no" formed by most of the parties, opposed to a presidential regime. Thereafter, the president was to be elected by direct universal suffrage for the first time since Louis Napoleon in 1848.[27]

1965 re-election

In December 1965, de Gaulle returned as president for a second seven-year term. In the first round he did not win the expected majority, receiving 45% of the vote. Both of his main rivals did better than expected; the leftist François Mitterrand received 32% and Jean Lecanuet, who advocated for what Life described as "Gaullism without de Gaulle", received 16%.[28] De Gaulle won a majority in the second round, with Mitterrand receiving 44.8%.[29]

Foreign policy

His expression, "Europe, from the Atlantic to the Urals", has often been cited throughout the history of European integration. It became, for the next ten years, a favourite political rallying cry of de Gaulle's. His vision stood in contrast to the Atlanticism of the United States and Britain, preferring instead a Europe that would act as a third pole between the United States and the Soviet Union. By including in his ideal of Europe all the territory up to the Urals, de Gaulle was implicitly offering détente to the Soviets. As the last chief of government of the Fourth Republic, de Gaulle made sure that the Treaty of Rome creating the European Economic Community was fully implemented, and that the British project of Free Trade Area was rejected, to the extent that he was sometimes considered as a "Father of Europe".[30]

NATO

De Gaulle hosted a superpower summit on 17 May 1960 for arms limitation talks and détente efforts in the wake of the 1960 U-2 incident between United States President Dwight Eisenhower, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, and United Kingdom Prime Minister Harold Macmillan.[31] De Gaulle's warm relations with Eisenhower were noticed by United States military observers at that time. De Gaulle told Eisenhower: "Obviously you cannot apologize but you must decide how you wish to handle this. I will do everything I can to be helpful without being openly partisan." When Khrushchev condemned the United States U-2 flights, de Gaulle expressed to Khrushchev his disapproval of 18 near-simultaneous secret Soviet satellite overflights of French territory; Khrushchev denied knowledge of the satellite overflights. Lieutenant General Vernon A. Walters wrote that after Khrushchev left, "De Gaulle came over to Eisenhower and took him by the arm. He took me also by the elbow and, taking us a little apart, he said to Eisenhower, 'I do not know what Khrushchev is going to do, nor what is going to happen, but whatever he does, I want you to know that I am with you to the end.' I was astounded at this statement, and Eisenhower was clearly moved by his unexpected expression of unconditional support". General Walters was struck by de Gaulle's "unconditional support" of the United States during that "crucial time".[32] De Gaulle then tried to revive the talks by inviting all the delegates to another conference at the Élysée Palace to discuss the situation, but the summit ultimately dissolved in the wake of the U-2 incident.[31]

In February 1966, France withdrew from the NATO Military Command Structure but remained within the organisation. De Gaulle, haunted by the memories of 1940, wanted France to remain the master of the decisions affecting it, unlike in the 1930s when it had to follow in step with its British ally. He also ordered all foreign military personnel to leave France within a year.[11]: 431 This latter action was particularly badly received in the US, prompting Dean Rusk, the US Secretary of State, to ask de Gaulle whether the removal of American military personnel was to include exhumation of the 50,000 American war dead buried in French cemeteries.[33]

European Economic Community (EEC)

De Gaulle, who in spite of recent history admired Germany and spoke excellent German,[34] as well as English,[35] established a good relationship with the aging West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer—culminating in the Elysee Treaty in 1963—and in the first few years of the Common Market, France's industrial exports to the other five members tripled and its farm export almost quadrupled. The franc became a solid, stable currency for the first time in half a century, and the economy mostly boomed. Adenauer however, all too aware of the importance of American support in Europe, gently distanced himself from the general's more extreme ideas, wanting no suggestion that any new European community would in any sense challenge or set itself at odds with the US. In Adenauer's eyes, the support of the US was more important than any question of European prestige.[36]

De Gaulle vetoed the British application to join the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1963, famously uttering the single word 'non' into the television cameras at the critical moment, a statement used to sum up French opposition towards Britain for many years afterwards.[37] Macmillan said afterwards that he always believed that de Gaulle would prevent Britain joining, but thought he would do it quietly, behind the scenes. He later complained privately that "all our plans are in tatters".[33]

During the establishment of the European Economic Community (EEC), de Gaulle helped precipitate the Empty Chair Crisis, one of the greatest crises in the history of the EEC. It involved the financing of the Common Agricultural Policy, but almost more importantly the use of qualified majority voting in the EC (as opposed to unanimity). In June 1965, after France and the other five members could not agree, de Gaulle withdrew France's representatives from the EC. Their absence left the organisation essentially unable to run its affairs until the Luxembourg compromise was reached in January 1966.[38] De Gaulle succeeded in influencing the decision-making mechanism written into the Treaty of Rome by insisting on solidarity founded on mutual understanding.[39] He vetoed Britain's entry into the EEC a second time, in June 1967.[40]

Recognition of the People's Republic of China

In January 1964, France was, after the UK, among the first of the major Western powers to open diplomatic relations with the People's Republic of China (PRC), which was established in 1949 and which was isolated on the international scene.[41] By recognizing Mao Zedong's government, de Gaulle signaled to both Washington and Moscow that France intended to deploy an independent foreign policy.[41] The move was criticized in the United States as it seemed to seriously damage US policy of containment in Asia.[41] De Gaulle justified this action by "the weight of evidence and reason", considering that China's demographic weight and geographic extent put it in a position to have a global leading role.[41] De Gaulle also used this opportunity to arouse rivalry between the USSR and China, a policy that was followed several years later by Henry Kissinger's "triangular diplomacy" which also aimed to create a Sino-Soviet split.[41]

Six-Day War

With tension rising in the Middle East in 1967, de Gaulle on 2 June declared an arms embargo against Israel, just three days before the outbreak of the Six-Day War. This, however, did not affect spare parts for the French military hardware with which the Israeli armed forces were equipped.[42] This was an abrupt change in French policy. In 1956, France, Britain and Israel had cooperated in an elaborate effort to retake the Suez Canal from Egypt. Israel's air force operated French Mirage and Mystère jets in the Six-Day War, and its navy was building its new missile boats in Cherbourg. Though paid for, their transfer to Israel was now blocked by de Gaulle's government. But they were smuggled out in an operation that drew further denunciations from the French government. The last boats took to the sea in December 1969, directly after a major deal between France and now-independent Algeria exchanging French armaments for Algerian oil.[43]

Under de Gaulle, following the independence of Algeria, France embarked on foreign policy more favorable to the Arab side. President de Gaulle's position in 1967 at the time of the Six-Day War played a part in France's new-found popularity in the Arab world.[44] Israel turned towards the United States for arms, and toward its own industry. In a televised news conference on 27 November 1967, de Gaulle described the Jewish people as "this elite people, sure of themselves and domineering".[45]

In his letter to David Ben-Gurion dated 9 January 1968, de Gaulle explained that he was convinced that Israel had ignored his warnings and overstepped the bounds of moderation by taking possession of Jerusalem, and Jordanian, Egyptian, and Syrian territory by force of arms. He felt Israel had exercised repression and expulsions during the occupation and that it amounted to annexation. He said that provided Israel withdrew its forces, it appeared that it might be possible to reach a solution through the UN framework which could include assurances of a dignified and fair future for refugees and minorities in the Middle East, recognition from Israel's neighbours, and freedom of navigation through the Gulf of Aqaba and the Suez Canal.[46]

Nigerian Civil War

The Eastern Region of Nigeria declared itself independent under the name of the Independent Republic of Biafra on 30 May 1967. On 6 July, the first shots in the Nigerian Civil War were fired, marking the start of a conflict that lasted until January 1970.[47] Under de Gaulle's leadership, France embarked on a period of interference outside the traditional French zone of influence. A policy geared toward the break-up of Nigeria put Britain and France into opposing camps. From August 1968, when its embargo was lifted, France provided limited and covert support to the Biafra rebels. Although French arms helped to keep Biafra in action for the final 15 months of the civil war, its involvement was seen as insufficient and counterproductive. The Biafran chief of staff stated that the French "did more harm than good by raising false hopes and by providing the British with an excuse to reinforce Nigeria."[48]

Vietnam War

In September 1966, in a famous speech in Phnom Penh in Cambodia, he expressed France's disapproval of the US involvement in the Vietnam War, calling for a US withdrawal from Vietnam as the only way to ensure peace.[49] De Gaulle considered the war to be the "greatest absurdity of the twentieth century".[50] De Gaulle conversed frequently with George Ball, United States President Lyndon Johnson's Under Secretary of State, and told Ball that he feared that the United States risked repeating France's tragic experience in Vietnam, which de Gaulle called "ce pays pourri" ("the rotten country"). Ball later sent a 76-page memorandum to Johnson critiquing Johnson's current Vietnam policy in October 1964.[51]

Vive le Québec libre!

In July 1967, de Gaulle visited Canada, which was celebrating its centenary with a world fair in Montreal, Expo 67. On 24 July, speaking to a large crowd from a balcony at Montreal's city hall, de Gaulle shouted "Vive le Québec libre! Vive le Canada français! Et vive la France!" (Long live free Quebec! Long live French Canada, and long live France!).[53] The Canadian media harshly criticized the statement, and Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson stated that "Canadians do not need to be liberated".[54] De Gaulle abruptly left Canada two days later, without proceeding to Ottawa as scheduled.[55] The speech was heavily criticized in both Canada and France,[56][57] but was seen as a watershed moment by the Quebec sovereignty movement.[58][59]

May 1968

De Gaulle's government was criticized within France, particularly for its heavy-handed style. While the written press and elections were free, and private stations such as Europe 1 were able to broadcast in French from abroad, the state's ORTF had a monopoly on television and radio. This monopoly meant that the government was in a position to directly influence broadcast news. In many respects, Gaullist France was conservative, Catholic, and there were few women in high-level political posts (in May 1968, the government's ministers were 100% male).[60] Many factors contributed to a general weariness of sections of the public, particularly the student youth, which led to the events of May 1968.

The mass demonstrations and strikes in France in May 1968 severely challenged De Gaulle's legitimacy. He and other government leaders feared that the country was on the brink of revolution or civil war. On 29 May, De Gaulle disappeared without notifying Prime Minister Pompidou or anyone else in the government, stunning the country. He fled to Baden-Baden in Germany to meet with General Massu, head of the French military there, to discuss possible army intervention against the protesters. De Gaulle returned to France after being assured of the military's support, in return for which De Gaulle agreed to amnesty for the 1961 coup plotters and OAS members.[61][62]

In a private meeting discussing the students' and workers' demands for direct participation in business and government he coined the phrase "La réforme oui, la chienlit non", which can be politely translated as 'reform yes, masquerade/chaos no.' It was a vernacular scatological pun meaning 'chie-en-lit, no' (shit-in-bed, no). The term is now common parlance in French political commentary, used both critically and ironically referring back to de Gaulle.[63]

But de Gaulle offered to accept some of the reforms the demonstrators sought. He again considered a referendum to support his moves, but on 30 May, Pompidou persuaded him to dissolve parliament (in which the government had all but lost its majority in the March 1967 elections) and hold new elections instead. The June 1968 elections were a major success for the Gaullists and their allies; when shown the spectre of revolution or civil war, the majority of the country rallied to him. His party won 352 of 487 seats,[64] but de Gaulle remained personally unpopular; a survey conducted immediately after the crisis showed that a majority of the country saw him as too old, too self-centered, too authoritarian, too conservative, and too anti-American.[61]

Retirement

De Gaulle resigned the presidency at noon, 28 April 1969,[65] following the rejection of his proposed reform of the Senate and local governments in a nationwide referendum. In an eight-minute televised speech two days before the referendum, De Gaulle warned that if he was "disavowed" by a majority of the voters, he would resign his office immediately. This ultimatum, coupled with increased De Gaulle fatigue among the French, convinced many that this was an opportunity to be rid of the 78-year-old general and the reform package was rejected. Two months later Georges Pompidou was elected as his successor.[66]

Legacy and evaluations

Because he commissioned the new constitution and was responsible for its overall framework, de Gaulle is sometimes described as the author of the constitution, although it was effectively drafted during the summer of 1958 by the Gaullist Michel Debré. The draft closely followed the propositions in de Gaulle’s speeches at Bayeux in 1946,[67] leading to a strong executive and to a rather presidential regime – the President being granted the responsibility of governing the Council of Ministers.[68][69]

Grosser argued that the enormous French effort to become independent of Washington in nuclear policy by building its own "force de frappe" had been a failure. The high budget cost came at the expense of weakening France's conventional military capabilities. Neither Washington nor Moscow pays much attention to the French nuclear deterrent one way or another. As a neutral force in world affairs, France does have considerable influence over its former colonies, much more than any other ex-colonial power. But the countries involved are not powerhouses, and the major neutral nations at the time, such as India, Yugoslavia and Indonesia, paid little attention to Paris.[70] He did not have a major influence at the United Nations.[71] While the French people supported and admired the foreign policy of Charles de Gaulle at the time and in retrospect, he made it all himself with scant regard to French public or elite opinion.[72][73]

References

- ↑ Philip M. Williams, Crisis and Compromise: Politics in the Fourth Republic (1958)

- ↑ Crozier, Brian; Mansell, Gerard (July 1960). "France and Algeria". International Affairs. Blackwell Publishing. 36 (3): 310. doi:10.2307/2610008. JSTOR 2610008. S2CID 153591784.

- 1 2 Jonathan, Fenby (2010). The General Charles de Gaulle and the France he saved. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9781847394101.

- ↑ W. Scott Haine (2000). The History of France. Greenwood Press. p. 180. ISBN 9780313303289.

- ↑ "Landslide Vote Repeated for de Gaulle – President of Fifth Republic – Sweeping Powers". The Times. 22 December 1958.

- ↑ Charles Sowerwine, France since 1870: Culture, Society and the Making of the Republic (2009) pp. 296–316

- ↑ Alexander Harrison, Challenging De Gaulle: The OAS and the Counterrevolution in Algeria, 1954–1962 (Praeger, 1989).

- ↑ Martin Evans, Algeria: France's Undeclared War (2012) excerpt and text search Archived 16 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Kolodziej, Edward A (1974). French International Policy under de Gaulle and Pompidou: The Politics of Grandeur. p. 618.

- ↑ Michael Mould (2011). The Routledge Dictionary of Cultural References in Modern French. Taylor & Francis. p. 331. ISBN 978-1-136-82573-6.

- 1 2 3 Crawley, Aidan (1969). De Gaulle: A Biography. Bobbs-Merrill Co. ISBN 978-0-00-211161-4. Archived from the original on 21 September 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ↑ "'Close shave!' How De Gaulle escaped assassin's bullets 60 years ago". France 24. 21 August 2022. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ↑ Willsher, Kim (22 August 2022). "France remembers De Gaulle's close escape depicted in The Day of the Jackal". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ↑ Ledsom, Alex (25 June 2018). "How Charles de Gaulle Survived Over Thirty Assassination Attempts". Culture Trip. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ↑ MacIntyre, Ben (24 July 2021). "The Jackal's lessons for would-be assassins". The Sunday Times. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ↑ Macksey, Kenneth (1966) Purnell's History of the Second World War: No. 123. "The Liberation of Paris"

- ↑ "New Year Brings in New Franc". The Times. 2 January 1960.

- ↑ France's GDP was slightly higher than the UK's at the beginning of the 19th century, with the UK surpassing France around 1870. See e.g., Maddison, Angus (1995). L'économie mondiale 1820–1992: analyse et statistiques. OECD Publishing. p. 248. ISBN 978-92-64-24549-5. Archived from the original on 14 December 2021. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ↑ Haine, W. Scott (1974). Culture and Customs of France. Westport CT: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2006. p. 315. ISBN 978-0-313-32892-3.

- ↑ The New France: A Society in Transition 1945–1977 (Third Edition) by John Ardagh

- ↑ "Marshal Juin Defended – General de Gaulle on Moral Issue". The Times. 8 April 1954.

- ↑ "Weekend of Rejoicing in France". The Times. 15 February 1960.

- ↑ Ledwidge p. 341

- ↑ "Independents Fear for France's Future – Gaullist Policy Queried". The Times. 18 August 1967.

- ↑ "De Gaulle Challenge to Parliament – To Retire if Referendum not Approved – Call to Nation before Debate on Censure Motion". The Times. 5 October 1962.

- ↑ "De Gaulle against the Politicians – Clear Issue for October Referendum – Assembly Election Likely after Solid Censure Vote". The Times. 6 October 1962.

- ↑ ""Yes" Reply for Gen. De Gaulle – Over 60 p.c. of Valid Votes – President Likely to Keep Office". The Times. 29 October 1962.

- ↑ "De Gaulle Has an Opposition". Life. 17 December 1965. p. 4. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- ↑ "France Again Elects Gen. De Gaulle – M. Mitterrand Concedes Within 80 Minutes – Centre Votes Evenly Divided". The Times. 20 December 1965.

- ↑ Warlouzet, 'De Gaulle as a Father of Europe Archived 19 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine' in Contemporary European History, 2011

- 1 2 1960: East-West summit in tatters after spy plane row Archived 23 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine. BBC.co.uk; accessed 7 June 2016.

- ↑ Walter, Vernon A. (2007) [1974]. "General De Gaulle in Action: 1960 Summit Conference". Studies in Intelligence. 38 (5). Archived from the original on 27 September 2012. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- 1 2 Holland, Robert (1991) Fontana History of England – Britain & the World Role

- ↑ Régis Debray (1994) Charles de Gaulle: Futurist of the Nation translated by John Howe, Verso, New York, ISBN 0-86091-622-7; a translation of Debray, Régis (1990) A demain de Gaulle Gallimard, Paris, ISBN 2-07-072021-7

- ↑ Rowland, Benjamin M. (16 August 2011). Charles de Gaulle's Legacy of Ideas. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-6454-9. Archived from the original on 8 April 2017. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Time, 8 August 1960

- ↑ Richards, Denis & Quick, Antony (1974) Twentieth Century Britain

- ↑ "France Ends Boycott of Common Market – No Winners or Losers after Midnight Agreement". The Times. 31 January 1966.

- ↑ "De Gaulle and Europe". Fondation Charles de Gaulle. Archived from the original on 18 November 2006.

- ↑ "European NAvigator (ENA) – General de Gaulle's second veto". Archived from the original on 23 February 2010. Retrieved 22 October 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gosset, David (8 January 2009). "A Return to De Gaulle's 'Eternal China'". Greater China. Asia Times. Archived from the original on 19 January 2009. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- ↑ "French Emphasis on Long-Term Issues". The Times. 7 June 1967.

- ↑ Geller, Doron "The Cherbourg Boats". Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ↑ "De Gaulle and the Third World". Fondation Charles de Gaulle. Archived from the original on 18 November 2006.

- ↑ "France-Israel: from De Gaulle's arms embargo to Sarkozy's election". Ejpress.org. Archived from the original on 2 September 2013.

- ↑ "Text of de Gaulle's Answer to Letter From Ben-Gurion". The New York Times. 10 January 1968. Archived from the original on 22 July 2018. Retrieved 22 July 2018.

- ↑ "920 Days of Fighting, Death and Hunger". The Times. 12 January 1970.

- ↑ Saha, Santosh C. (2006). Perspectives on Contemporary Ethnic Conflict: Primal Violence Or the Politics of Conviction?. Lanham MD: Lexington Books. pp. 184, 344. ISBN 978-0-7391-1085-0.

- ↑ "Allocution prononcée à la réunion populaire de Phnom-Penh, 1er septembre 1966" [Address by the President of the French Republic (General de Gaulle), Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 1 September 1966]. Fondation Charles de Gaulle. 2008. Archived from the original on 18 November 2008.

- ↑ Gowland, David; Turner, Arthur: Reluctant Europeans: Britain and European Integration, 1945–1998 Archived 14 December 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Routledge, p. 166. Accessed on 31 October 2019.

- ↑ Karnow, Stanley (1983). Vietnam: A History. New York: The Viking Press. p. 405. ISBN 9780670746040. OCLC 779626081.

- ↑ Samy Mesli, historien. "Charles de Gaulle au Québec 24 juillet 1967". Fondation Lionel-Groulx, 2017—2018 (in French). Charles de Gaulle au Québec en 1967. Retrieved 6 August 2023.

- ↑ Depoe, Norman (24 July 1967). "Vive le Québec libre!". On This Day. CBC News. Archived from the original on 1 May 2012.

- ↑ Gillan, Michael (26 July 1967). "Words unacceptable to Canadians: De Gaulle Rebuked by Pearson". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. pp. 1, 4.

- ↑ George Sherman, "De Gaulle Ends Visit in Canadian Dispute," The Evening Star, 26 July 1967, p. 1.

- ↑ "Gen De Gaulle Rebuked by Mr Pearson – Canada Rejects Efforts to Destroy Unity – Quebec Statements Unacceptable". The Times. London, UK. 26 July 1967.

- ↑ Spicer, Keith (27 July 1967). "Paris perplexed by De Gaulle's Quebec conduct". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. p. 23.

- ↑ "Levesque pays tribute to Charles de Gaulle". The Leader-Post. Regina, Saskatchewan. Reuters. 1 November 1977. p. 2. Archived from the original on 14 December 2021. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ↑ "De Gaulle and "Vive le Québec Libre"". The Canadian Encyclopedia. 2012. Archived from the original on 19 January 2012.

- ↑ "Les femmes et le pouvoir". 29 May 2007. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 13 January 2009.

of the first eleven governments of the Fifth Republic, four contained no women whatsoever.

- 1 2 Dogan, Mattei (1984). "How Civil War Was Avoided in France". International Political Science Review. 5 (3): 245–277. doi:10.1177/019251218400500304. JSTOR 1600894. S2CID 144698270.

- ↑ "Autocrat of the Grand Manner". The Times. 28 April 1969.

- ↑ Crawley (p. 454) also writes that de Gaulle was undoubtedly using the term in his barrack-room style to mean 'shit in the bed'. De Gaulle had said it first in Bucharest while on an official visit from which he returned on 19 May 1968. Pompidou told the press that de Gaulle used the phrase after the cabinet meeting on 19 May.

- ↑ "Dropping the Pilot". The Times. 11 July 1968.

- ↑ "Press Release re Resignation". Fondation Charles de Gaulle. 2008. Archived from the original on 18 November 2008.

- ↑ Serge Berstein; Jean-Pierre Rioux (2000). The Pompidou Years, 1969–1974. Cambridge UP. pp. 4–8. ISBN 978-0-521-58061-8. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- ↑ Charles De Gaulle (June 16, 1946). "Discours de Bayeux [Speech of Bayeux]" (in French). charles-de-gaulle.org. Archived from the original on May 17, 2011.

- ↑ Bell, John; Boyron, Sophie; Whittaker, Simon (2008-03-27). Principles of French Law. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199541393.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-954139-3.

- ↑ Elliott, Jeanpierre & Vernon 2006, p. 69–70.

- ↑ Kulski 1966, pp. 314–320.

- ↑ Kulski 1966, pp. 321–389.

- ↑ Grosser, French foreign policy under De Gaulle (1967) pp 128–144.

- ↑ Kulski 1966, pp. 37–38.

Bibliography

- Elliott, Catherine; Jeanpierre, Eric; Vernon, Catherine (2006). French Legal System (Second ed.). Harlow, England: Pearson/Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-1161-3. OCLC 70107160.

- Kulski, Władysław Wszebór (1966). De Gaulle and the World: The Foreign Policy of the Fifth French Republic. Syracuse UP. ISBN 978-0815600527.

Further reading

Politics

- Berstein, Serge, and Peter Morris. The Republic of de Gaulle 1958–1969 (The Cambridge History of Modern France) (2006) excerpt and text search

- Cameron, David R. and Hofferbert, Richard I. "Continuity and Change in Gaullism: the General's Legacy." American Journal of Political Science 1973 17(1): 77–98. ISSN 0092-5853, a statistical analysis of the Gaullist voting coalition in elections 1958–73 Fulltext: . JSTOR 2110475.

- Cogan, Charles G. "The Break-up: General de Gaulle's Separation from Power," Journal of Contemporary History Vol. 27, No. 1 (Jan. 1992), pp. 167–199, re: 1969 . JSTOR 260783.

- Diamond, Robert A. France under de Gaulle (Facts on File, 1970), highly detailed chronology 1958–1969. 319pp

- Furniss, Edgar J. Jr. De Gaulle and the French Army. (1964)

- Gough, Hugh and Horne, John, eds. De Gaulle and Twentieth-Century France. (1994). 158 pp. essays by experts

- Hauss, Charles. Politics in Gaullist France: Coping with Chaos (1991) online edition Archived 28 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Hoffmann, Stanley. Decline or Renewal? France since the 1930s (1974) online edition Archived 2008-12-03 at the Wayback Machine

- Jackson, Julian. "General de Gaulle and His Enemies: Anti-Gaullism in France Since 1940," Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 6th Ser., Vol. 9 (1999), pp. 43–65 . JSTOR 3679392.

- Merom, Gil. "A 'Grand Design'? Charles de Gaulle and the End of the Algerian War," Armed Forces & Society(1999) 25#2 pp: 267–287 online

- Nester, William R. De Gaulle's Legacy: The Art of Power in France's Fifth Republic (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014)

- Northcutt, Wayne. Historical Dictionary of the French Fourth and Fifth Republics, 1946–1991 (1992)

- Pierce, Roy, "De Gaulle and the RPF—A Post-Mortem," The Journal of Politics Vol. 16, No. 1 (Feb. 1954), pp. 96–119 . JSTOR 2126340.

- Rioux, Jean-Pierre, and Godfrey Rogers. The Fourth Republic, 1944–1958 (The Cambridge History of Modern France) (1989)

- Shepard, Todd. The Invention of Decolonization: The Algerian War and the Remaking of France. (2006). 288 pp.

- Williams, Philip M. and Martin Harrison. De Gaulle's Republic (1965) online edition Archived 28 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

Foreign policy

- Bozo, Frédéric. Two Strategies for Europe: De Gaulle, the United States and the Atlantic Alliance (2000)

- Gordon, Philip H. A Certain Idea of France: French Security Policy and the Gaullist Legacy (1993) online edition Archived 2008-04-21 at the Wayback Machine

- Grosser, Alfred. French foreign policy under De Gaulle (Greenwood Press, 1977)

- Hoffmann, Stanley. "The Foreign Policy of Charles de Gaulle." in The Diplomats, 1939–1979 (Princeton University Press, 2019) pp. 228–254. online

- Kolodziej, Edward A. French International Policy under de Gaulle and Pompidou: The Politics of Grandeur (1974) online edition Archived 28 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Kulski, W. W. De Gaulle and the World: The Foreign Policy of the Fifth French Republic (1966) online free to borrow

- Logevall, Fredrik. "De Gaulle, Neutralization, and American Involvement in Vietnam, 1963–1964," Pacific Historical Review 61#1 (Feb. 1992), pp. 69–102 . JSTOR 3640789.

- Mahan, E. Kennedy, De Gaulle and Western Europe. (2002). 229 pp.

- Mangold, Peter. The Almost Impossible Ally: Harold Macmillan and Charles de Gaulle. (2006). 275 pp. IB Tauris, London, ISBN 978-1-85043-800-7

- Martin, Garret Joseph. General de Gaulle's Cold War: Challenging American Hegemony, 1963–1968 (Berghahn Books; 2013) 272 pages

- Moravcsik, Andrew. "Charles de Gaulle and Europe: The New Revisionism." Journal of Cold War Studies (2012) 14#1 pp: 53–77.

- Nuenlist, Christian. Globalizing de Gaulle: International Perspectives on French Foreign Policies, 1958–1969 (2010)

- Newhouse, John. De Gaulle and the Anglo-Saxons (New York: Viking Press, 1970)

- Paxton, Robert O. and Wahl, Nicholas, eds. De Gaulle and the United States: A Centennial Reassessment. (1994). 433 pp.

- White, Dorothy Shipley. Black Africa and de Gaulle: From the French Empire to Independence. (1979). 314 pp.