Jajinci

Јајинци | |

|---|---|

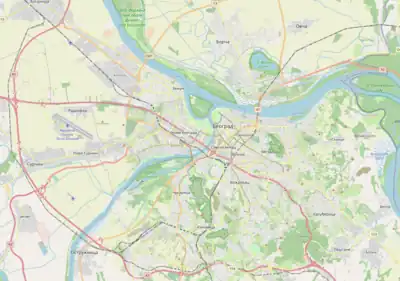

Jajinci Location within Belgrade | |

| Coordinates: 44°44′N 20°29′E / 44.733°N 20.483°E | |

| Country | |

| Region | |

| Municipality | Voždovac |

| Area | |

| • Total | 5.13 km2 (1.98 sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Area code | +381(0)11 |

| Car plates | BG |

Jajinci (Serbian Cyrillic: Јајинци, pronounced [jâjiːntsi]) is an urban neighborhood located in the municipality of Voždovac, in Belgrade, Serbia. It was the site of the worst carnage in Serbia during World War II when German occupational forces executed nearly 80,000 people, many of them prisoners of the nearby Banjica concentration camp. Jewish women and children from German Sajmište concentration camp, killed in a special gas truck on their way to Belgrade were also buried here.

Location

Jajinci is located in the Lipnica creek valley. Once a small village far from downtown Belgrade, Jajinci today has grown into one continuous metropolitan area with the rest of the city. It borders the neighborhoods of Banjica on the north, Kumodraž on the east, and Selo Rakovica on the south. The eastern border of the neighborhood is marked by the Jelezovac creek, which also forms a border with the municipality of Rakovica.

Characteristics

Boža Radulović, merchant, brought the first car in Belgrade on 3 April 1903, and hired a photographer Sreten Kostić as his driver. Kostić, who later became a professional, even a royal driver, built a house in Jajinci in the 1920s, close to the popular kafana "Župa". There, at the curve on the Avala Road, Kostić placed the first modern traffic sign in Belgrade, which said држи десно, or "keep right". Thanks to him, Avala Road became the first concrete paved street in Belgrade, and Župa location became a pitstop in the first races organized in the city. In 2018, two streets in the vicinity of the former kafana were named after Sreten Kostić and Župa.[1][2][3]

The settlement spreads from the central street, the Boulevard of Liberation, which starts in central Belgrade (the Slavija square). A former village and separate settlement, Jajinci is today a local community (mesna zajednica) within the municipality of Voždovac. Unlike neighboring Banjica, it was never developed with high modern buildings and remained a settlement of smaller, family houses, but did evolve from agricultural into a typical suburban area with most inhabitants working in Belgrade.

A large rasadnik (nursery garden) is located in the north of the neighborhood, and the "Jajinci" memorial park is in the southern section.

Arrangement of the large forest area within the memorial park began in the 1950s. By 2010, the forested complex covered 81.45 hectares (201.3 acres).[4]

In September 2023 city's plan for urbanization of the southwest section of the neighborhood, along the Jakova Galusa Street, was announced. In the area of 12 ha (30 acres) numerous commercial and residential structures are planned, which would lift a number of inhabitants in this section from 357 to 1,050.[5]

Mala Utrina

A western sub-settlement of Jajinci located along the lower course of the Lipovica creek, near where it flows into the Jelezovac. It is a direct extension of the rasadnik in the north.

It is situated 500 m (1,600 ft) from the Banjica direction. As of 2018, it still lacked proper communal infrastructure.[6]

Maxima

A southern sub-settlement of Jajinci. Because of luxury houses, mansions and villas, people call this part of Jajinci New Dedinje.

Population

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1910 | 458 | — |

| 1921 | 489 | +6.8% |

| 1931 | 922 | +88.5% |

| 1948 | 875 | −5.1% |

| 1953 | 1,080 | +23.4% |

| 1961 | 2,572 | +138.1% |

| 1971 | 3,879 | +50.8% |

| 1981 | 4,386 | +13.1% |

| 1991 | 4,396 | +0.2% |

| 2002 | 6,986 | +58.9% |

| 2011 | 8,876 | +27.1% |

| Source: [7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17] | ||

Jajinci was a separate settlement until 1972 when it was officially annexed into the Belgrade City Proper (uža teritorija grada). In the 20th century it experienced constant population growth until the 1990s. The Yugoslav Wars brought a large influx of refugees, and Jajinci continued to grow in the early 2000s.

World War II

A former military shooting ground near Jajinci was used by the Nazis as an execution place for almost 80,000 people in the period between 1941 and 1944, most of them Serbs, Jews and Roma. Victims were mostly gathered and sent to the execution by the occupational Nazi forces in Serbia, but also by the Independent State of Croatia authorities and the Serbian Quisling regime. Many of them were prisoners, either Communists or public figures opposing the German occupation, from the Banjica concentration camp, but the detainees and prisoners from Staro Sajmište concentration camp, and Gestapo's and special police prisons. Jajinci is the largest World War II execution site in Serbia.[18]

First arrangement of the area into an open memorial was finished in 1951.[18] A large memorial park, with a monument to the victims, was opened on 20 October 1964, marking the 20th anniversary of the Partisan army entering Belgrade.

City authorities tried to construct the proper memorial for a long time. In 1987, city announced the third design competition for the memorial. Among 42 submitted works, the commission decided for the work of Vojin Stojić. Architect Bogdan Bogdanović, head of the commission, noted that such work can't be done in concrete, as suggested by the author, so instead a sculpture of stainless steel was made. It was officially dedicated in 1988.[19]

Green and flat area of the Memorial Park Jajinci served as an open picnic and excursion area for decades, variously used for pets, sunbathing, children's birthdays, sports activities and auto races. Deeming such use of the area with tens of thousands of executed victims buried under the ground anti-civilized, Belgrade Museum of Genocide Victims officially asked the government on 29 December 2021 to become administrator of the memorial. The government remained silent until November 2022 when videos and photos of quads revving engines and speeding over the burial ground surfaced. Though this wasn't the first time it happened, this time it caused a public outcry, and government decided to hand over the memorial park to the museum via the expedited procedure.[20]

References

- ↑ Moderni žurnal (12 March 2018). "Kako je Boža Radulović zadužio Beograd" [How Boža Radulović obliged Belgrade]. Auto Museum Belgrade (in Serbian).

- ↑ Službeni list Grada Beograda, No. 119/18 (PDF). City of Belgrade. 21 December 2018. p. 57. ISSN 0350-4727.

- ↑ Momčilo Petrović (5 March 2023). Први семафор [First traffic light]. Politika-Magazin, No. 1327 (in Serbian). p. 23.

- ↑ Anica Teofilović; Vesna Isajlović; Milica Grozdanić (2010). Пројекат "Зелена регулатива Београда" - IV фаѕа: План генералне регулације система зелених површина Београда (концепт плана) [Project "Green regulations of Belgrade" - IV phase: Plan of the general regulation of the green area system in Belgrade (concept of the plan)] (PDF). Urbanistički zavod Beograda. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-01-15. Retrieved 2020-05-08.

- ↑ Daliborka Mučibabić (7 September 2023). Градитељски преображај насеља Јајинци [Architectural makeover of Jajinci neighborhood]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 15.

- ↑ Zdravko Zdravković (8 March 2018). "Kanalizacija kao Potemkinova sela" [Sewage like Potemkin village]. Politika (in Serbian).

- ↑ Претходни резултати пописа становништва и домаће стоке у Краљевини Србији 31 декембра 1910 године, Књига V, стр. 12 [Preliminary results of the census of population and husbandry in Kingdom of Serbia on 31 December 1910, Vol. V, page 12]. Управа државне статистике, Београд (Administration of the state statistics, Belgrade). 1911.

- ↑ Final results of the census of population from 31 January 1921. Kingdom of Yugoslavia - General State Statistics, Sarajevo. June 1932.

- ↑ Final results of the census of population from 31 March 1931. Kingdom of Yugoslavia - General State Statistics, Belgrade. 1937.

- ↑ Final results of the population census of March 15th 1948, Volume IX, Population by ethnic nationality. Federal Statistical, Belgrade. 1954.

- ↑ Popis stanovništva 1953, Stanovništvo po narodnosti (pdf). Savezni zavod za statistiku, Beograd.

- ↑ Popis stanovništva 1961, Stanovništvo prema nacionalnom sastavu (pdf). Savezni zavod za statistiku, Beograd.

- ↑ Popis stanovništva 1971, Stanovništvo prema nacionalnom sastavu (pdf). Savezni zavod za statistiku, Beograd.

- ↑ Osnovni skupovi stanovništva u zemlji – SFRJ, SR i SAP, opštine i mesne zajednice 31.03.1981, tabela 191. Savezni zavod za statistiku (txt file). 1983.

- ↑ Stanovništvo prema migracionim obeležjima – SFRJ, SR i SAP, opštine i mesne zajednice 31.03.1991, tabela 018. Savezni zavod za statistiku (txt file).

- ↑ Popis stanovništva po mesnim zajednicama, Saopštenje 40/2002, page 4. Zavod za informatiku i statistiku grada Beograda. 26 July 2002.

- ↑ Stanovništvo po opštinama i mesnim zajednicama, Popis 2011. Grad Beograd – Sektor statistike (xls file). 23 April 2015.

- 1 2 Rajna Popović (18 December 2022). "Jajinci će konačno postati spomen-područje" [Jajinci will finally become a memorial area]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 08.

- ↑ Špiro Solomun (20 November 2019). "Memorijali Beograda" [Memorials of Belgrade]. Politika (in Serbian). pp. 26–27.

- ↑ Politika's Society desk (15 November 2022). "Muzej žrtava genocida preuzima brigu o spomen-području Jajinci" [Museum of Genocide Victims taking over care of the Memorial Park Jajinci]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 07.