Islam in Albania (1800–1912) refers to the period that followed on after the conversion to Islam by a majority of Albanians in the 17th and 18th centuries. By the beginning of 19th century Islam had become consolidated within Albania and little conversion occurred. With the Eastern Crisis of the 1870s and its geo-political implications of partition for Albanians, the emerging National Awakening became a focal point of reflection and questioned the relationship between Muslim Albanians, Islam and the Ottoman Empire. These events and other changing social dynamics revolving around Islam would come to influence how Albanians viewed the Muslim faith and their relationship to it. Those experiences and views carried on in the 20th century had profound implications on shaping Islam in Albania that surfaced during the communist era.

Background

At the beginning of the 19th century Albanians were divided into three religious groups. Catholic Albanians who had some Albanian ethno-linguistic expression in schooling and church due to Austrian protection and Italian clerical patronage.[1] Orthodox Albanians under the Patriarchate of Constantinople had liturgy and schooling in Greek and toward the late Ottoman period mainly identified with Greek national aspirations.[1][2][3][4] While Muslim Albanians during this period formed around 70% of the overall Balkan Albanian population in the Ottoman Empire with an estimated population of more than a million.[1] With the rise of the Eastern Crisis, Muslim Albanians became torn between loyalties to the Ottoman state and the emerging Albanian nationalist movement.[5] Islam, the Sultan and the Ottoman Empire were traditionally seen as synonymous in belonging to the wider Muslim community.[6] While the Albanian nationalist movement advocated self-determination and strived to achieve socio-political recognition of Albanians as a separate people and language within the state.[7] Between 1839 and 1876, the Ottoman Empire initiated modernising government reforms during the Tanzimat period and the Albanian Ottoman elite opposed them, in particular of having Ottoman officials from other parts of the empire sent to govern Ottoman Albanian areas and the introduction of a new centralised military recruitment system.[8]

National Awakening and Islam

The Russo-Ottoman war of 1878 and the threat of partition of Ottoman Albanian inhabited areas amongst neighbouring Balkan states at the Congress of Berlin led to the emergence of the League of Prizren (1878–81) to prevent those aims.[5] The league began as an organisation advocating Islamic solidarity and restoration of the status quo (pre-1878).[5] In time it also included Albanian national demands such as the creation of a large Albanian vilayet or province which led to its demise by the Ottoman Empire.[9] The Ottoman Empire viewed Muslim Albanians as a bulwark to further encroachment by Christian Balkan states to its territory.[6] It therefore opposed emerging Albanian national sentiments and Albanian language education amongst its Muslim component that would sever Muslim Albanians from the Ottoman Empire.[6] During this time the Ottoman Empire appealed to pan-Islamic identity and attempted to console Muslim Albanians for example by employing mainly them in the Imperial Palace Guard and offering their elite socio-political and other privileges.[6][10] Of the Muslim Albanian elite of the time, though there were reservations regarding Ottoman central government control they remained dependent on state civil, military and other employment.[11] For that elite, remaining within the empire meant that Albanians were a dynamic and influential group in the Balkans, while within an independent Albania connoted being surrounded by hostile Christian neighbours and open to the dictates of other European powers.[11] Wars and socio-political instability resulting in increasing identification with the Ottoman Empire amongst some Muslims within the Balkans during the late Ottoman period made the terms Muslim and Turk synonymous.[12] In this context, Muslim Albanians of the era were conferred and received the term Turk while preferring to distance themselves from ethnic Turks.[12][13] This practice has somewhat continued amongst Balkan Christian peoples in contemporary times who still refer to Muslim Albanians as Turks, Turco-Albanians, with often pejorative connotations and historic negative socio-political repercussions.[14][15][16][17][18][13] During this time small numbers of Slavic Muslims, Bosniaks from the Herzegovina Mostar area migrated due to the Herzegovina Uprising (1875) and Slavic Muslims expelled (1878) by Montenegrin forces from Podgorica both settled in a few settlements in north-western Albania.[19][20][21][22]

These geo-political events nonetheless pushed Albanian nationalists, including large numbers of Muslims, to distance themselves from the Ottomans, Islam and the then emerging pan-Islamic Ottomanism of Sultan Abdulhamid II.[7][23] Another factor overlaying these concerns during the Albanian National Awakening (Rilindja) period were thoughts that Western powers would only favour Christian Balkan states and peoples in the anti Ottoman struggle.[23] During this time Albanian nationalists conceived of Albanians as a European people who under Skanderbeg resisted the Ottoman Turks that later subjugated and cut the Albanians off from Western European civilisation.[23] Another measure for nationalists promoting the Skanderbeg myth among Albanians was for them to turn their backs on their Ottoman heritage which was viewed as being the source of the Albanians' predicament.[24][25] From 1878 onward Albanian nationalists and intellectuals, some who emerged as the first modern Albanian scholars were preoccupied with overcoming linguistic and cultural differences between Albanian subgroups (Gegs and Tosks) and religious divisions (Muslim and Christians).[26] Muslim (Bektashi) Albanians were heavily involved with the Albanian National Awakening producing many figures like Faik Konitza, Ismail Qemali, Midhat Frashëri, Shahin Kolonja and others advocating for Albanian interests and self-determination.[7][27][28][29][30] Representing the complexities and interdependencies of both Ottoman and Albanians worlds, these individuals and others during this time also contributed to the Ottoman state as statesmen, military personnel, religious figures, intellectuals, journalists and being members of Union and Progress (CUP) movement.[10][27][31] Such figures were Sami Frashëri who reflecting on Islam and Albanians viewed Bektashism as a milder syncretic form of Islam with Shiite and Christian influences that could overcome Albanian religious divisions through mass conversion to it.[23] The Bektashi Sufi order during the late Ottoman period, with around 20 tekkes in Southern Albania also played a role during the Albanian National Awakening by cultivating and stimulating Albanian language and culture and was important in the construction of national Albanian ideology.[1][32][33][34][35]

Late Ottoman period

During the late Ottoman period, Muslims inhabited compactly the entire mountainous and hilly hinterland located north of the Himarë, Tepelenë, Këlcyrë and Frashëri line that encompasses most of the Vlorë, Tepelenë, Mallakastër, Skrapar, Tomorr and Dishnicë regions.[36] There were intervening areas where Muslims lived alongside Albanian speaking Christians in mixed villages, towns and cities with either community forming a majority or minority of the population.[36] In urban settlements Muslims were almost completely a majority in Tepelenë and Vlorë, a majority in Gjirokastër with a Christian minority, whereas Berat, Përmet and Delvinë had a Muslim majority with a large Christian minority.[36] A Muslim population was also located in Konispol and some villages around the town.[36] While the Ottoman administrative sancaks or districts of Korçë and Gjirokastër in 1908 contained a Muslim population that numbered 95,000 in contrast to 128,000 Orthodox inhabitants.[37] Apart from small and spread out numbers of Muslim Romani, Muslims in these areas that eventually came to constitute contemporary southern Albania were all Albanian speaking Muslims.[36][38] In southern Albania during the late Ottoman period being Albanian was increasingly associated with Islam, while from the 1880s the emerging Albanian National Movement was viewed as an obstacle to Hellenism within the region.[39][40] Some Orthodox Albanians began to affiliate with the Albanian National movement causing concern for Greece and they worked together with Muslim Albanians regarding shared social and geo-political Albanian interests and aims.[40][41][42]

In central and southern Albania, Muslim Albanian society was integrated into the Ottoman state.[43] It was organised into a small elite class owning big feudal estates worked by a large peasant class, both Christian and Muslim though few other individuals were also employed in the military, business, as artisans and in other professions.[43][44] While northern Albanian society was little integrated into the Ottoman world.[45] Instead it was organised through a tribal structure of clans (fis) of whom many were Catholic with others being Muslim residing in mountainous terrain that Ottomans often had difficulty in maintaining authority and control.[45] When religious conflict occurred it was between clans of opposing faiths, while within the scope of clan affiliation religious divisions were sidelined.[46] Shkodër was inhabited by a Muslim majority with a sizable Catholic minority.[45] In testimonies of the late Ottoman period they describe the Muslim conservatism of the Albanian population in central and northern Albania which in places such as Shkodër was expressed sometimes in the form of discrimination against Catholic Albanians.[46][47][48] Other times Muslim and Catholic Albanians cooperated with each other for example forming the Shkodër committee during time of the League of Prizren.[46] In matrimonial affairs during the Ottoman period it was permissible for Muslim males to marry Christian females and not vice versa.[49] During the 19th century however, in areas of Northern Albania powerful and observant Catholics married Muslim women who converted upon marriage.[49] Conversions to Islam from Christianity by Albanians still occurred during the early years of the 20th century.[50]

Mosque of Neshat Pasha in Vlorë.

Mosque of Neshat Pasha in Vlorë. Et'hem Bey Mosque, one of the oldest mosques in Tiranë.

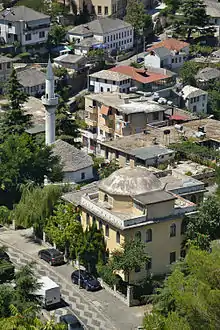

Et'hem Bey Mosque, one of the oldest mosques in Tiranë..jpg.webp) Bazaar Mosque in Gjirokastër.

Bazaar Mosque in Gjirokastër. Kokonozi Mosque in Tiranë.

Kokonozi Mosque in Tiranë. Teqe Mosque in Gjirokastër.

Teqe Mosque in Gjirokastër. Tanners' Mosque in Tiranë.

Tanners' Mosque in Tiranë.

In 1908 the Young Turk revolution, in part instigated by Muslim Albanian Ottoman officials and troops with CUP leanings deposed Sultan Abdul Hamit II and installed a new government which promised reforms.[31][51][52][53] In 1908, an alphabet congress with Muslim, Catholic and Orthodox delegates in attendance agreed to adopt a Latin character-based Albanian alphabet and the move was considered an important step for Albanian unification.[54][55][56][51] Opposition toward the Latin alphabet came from some Albanian Muslims and clerics who with the Ottoman government preferred an Arabic-based Albanian alphabet, due to concerns that a Latin alphabet undermined ties with the Muslim world.[54][55][56] Due to the alphabet matter, relations between Albanian nationalists, many of whom were Muslim, and Ottoman authorities broke down.[51] In the late Ottoman period Bektashi Muslims in Albania distanced themselves from Albanian Sunnis who opposed Albanian independence.[57] The Ottoman government was concerned that Albanian nationalism might inspire other Muslim nationalities toward such initiatives and threaten the Muslim-based unity of the empire.[58] Overall Albanian nationalism was a reaction to the gradual breakup of the Ottoman Empire and a response to Balkan and Christian national movements that posed a threat to an Albanian population that was mainly Muslim.[59] Albanian nationalism was supported by many Muslim Albanians and the Ottomans adopted measures to repress it which toward the end of Ottoman rule resulted in the occurrence of two Albanian revolts.[58][60] The first revolt was during 1910 in northern Albania and Kosovo reacting toward the new Ottoman government policy of centralization.[61] The other revolt in the same areas was in 1912 that sought Albanian political and linguistic self-determination under the bounds of the Ottoman Empire and with both revolts many of the leaders and fighters were Muslim Albanians.[62][52] These Albanian revolts and eventual independence (1912) were turning points that impacted the Young Turk government which increasingly moved from a policy direction of pan-Ottomanism and Islam toward a singular national Turkish outlook.[10][63] With a de-emphasis of Islam, the Albanian national movement gained the strong support of two Adriatic sea powers Austria-Hungary and Italy who were concerned about pan-Slavism in the wider Balkans and Anglo-French hegemony purportedly represented through Greece in the area.[42]

See also

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 Gawrych 2006, pp. 21–22.

- ↑ Skendi 1967a, p. 174.

- ↑ Nitsiakos 2010, p. 56. "The Orthodox Christian Albanians, who belonged to the rum millet, identified themselves to a large degree with the rest of the Orthodox, while under the roof of the patriarchate and later the influence of Greek education they started to form Greek national consciousness, a process that was interrupted by the Albanian national movement in the 19th century and subsequently by the Albanian state."; p. 153. "The influence of Hellenism on the Albanian Orthodox was such that, when the Albanian national idea developed, in the three last decades of the 19th century, they were greatly confused regarding their national identity."

- ↑ Skoulidas 2013. para. 2, 27.

- 1 2 3 Gawrych 2006, pp. 43–53.

- 1 2 3 4 Gawrych 2006, pp. 72–86.

- 1 2 3 Gawrych 2006, pp. 86–105.

- ↑ Jelavich 1983, p. 363.

- ↑ Gawrych 2006, pp. 60–70.

- 1 2 3 Karpat 2001, pp. 369–370.

- 1 2 Kokolakis 2003, p. 90."Άσχετα από τις επιφυλάξεις που διατηρούσε απέναντι στην κεντρική εξουσία, η ηγετική μερίδα των Τουρκαλβανών παρέμενε εξαρτημένη από τους κρατικούς «λουφέδες» που αποκόμιζαν οι εκπρόσωποι της στελεχώνοντας τις πολιτικές και στρατιωτικές θέσεις της Αυτοκρατορίας• γνώριζε άλλωστε καλά ότι το αλβανικό στοιχείο θα έπαιζε πολύ σημαντικότερο ρόλο στα Βαλκάνια στα πλαίσια μιας ενιαίας Οθωμανικής Αυτοκρατορίας, παρά ως πυρήνας ενός κράτους χωριστού, τριγυρισμένου από εχθρικά χριστιανικά βασίλεια και εκτεθειμένου στις μηχανορραφίες των ευρωπαϊκών δυνάμεων." "[Regardless of the reservations maintained against the central power, the leading portion of Muslim Albanians remained dependent on the state "lufedes" realized by being the representatives recruited in the civil and military posts of the Empire, they also knew well that the Albanian element would play a very important role in the Balkans in a single Ottoman Empire, rather than in a core of a separate state, surrounded by hostile Christian kingdoms and exposed to the machinations of the European powers]."

- 1 2 Karpat 2001, p. 342."After 1856, and especially after 1878, the terms Turk and Muslim became practically synonymous in the Balkans. An Albanian who did not know one word of Turkish thus was given the ethnic name of Turk and accepted it, no matter how much he might have preferred to distance himself from the ethnic Turks."

- 1 2 Hart 1999, p. 197."Christians in ex-Ottoman domains have frequently and strategically conflated the terms Muslim and Turk to ostracize Muslim or Muslim-descended populations as alien (as in the current Serb-Bosnian conflict; see Sells 1996), and Albanians, though of several religions, have been so labeled."

- ↑ Megalommatis 1994, p. 28."Muslim Albanians have been called "Turkalvanoi" in Greek, and this is pejorative."

- ↑ Nikolopoulou 2013, p. 299. "Instead of the term "Muslim Albanians", nationalist Greek histories use the more known, but pejorative, term "Turkalbanians".

- ↑ League of Nations (October 1921). "Albania". League of Nations –Official Journal. 8: 893. "The memorandum of the Albanian government… The memorandum complains that the Pan-Epirotic Union misnames the Moslem Albanians as "Turco-Albanians""

- ↑ Mentzel 2000, p. 8. "The attitude of non Muslim Balkan peoples was similar. In most of the Balkans, Muslims were "Turks" regardless of their ethno-linguistic background. This attitude changed significantly, but not completely, over time."

- ↑ Blumi 2011, p. 32. "As state policy, post- Ottoman "nations" continue to sever most of their cultural, socioeconomic, and institutional links to the Ottoman period. At times, this requires denying a multicultural history, inevitably leading to orgies of cultural destruction (Kiel 1990; Riedlmayer 2002). As a result of this strategic removal of the Ottoman past—the expulsion of the "Turks" (i.e., Muslims); the destruction of buildings; the changing of names of towns, families, and monuments; and the "purification" of languages—many in the region have accepted the conclusion that the Ottoman cultural, political, and economic infrastructure was indeed an "occupying," and thus foreign, entity (Jazexhi 2009). Such logic has powerful intuitive consequences on the way we write about the region's history: If Ottoman Muslims were "Turks" and thus "foreigners" by default, it becomes necessary to differentiate the indigenous from the alien, a deadly calculation made in the twentieth century with terrifying consequences for millions."

- ↑ Tošić 2015, pp. 394–395.

- ↑ Steinke & Ylli 2013, p. 137 "Das Dorf Borakaj (Borak/Borake), zwischen Durrës und Tirana in der Nähe der Kleinstadt Shijak gelegen, wird fast vollständig von Bosniaken bewohnt. Zu dieser Gruppe gehören auch die Bosniaken im Nachbarort Koxhas."; p. 137. "Die Bosniaken sind wahrschlich nach 1875 aus der Umgebung von Mostar, und zwar aus Dörfern zwischen Mostar und Čapljina, nach Albanien gekommen... Einzelne bosnische Familien wohnen in verschiedenen Städten, vie in Shijak, Durrës. Die 1924 nach Libofsha in der Nähe von Fier eingewanderte Gruppe ist inzwischen sprachlich fast vollständig assimiliert, SHEHU-DIZDARI-DUKA (2001: 33) bezeichnet sie ehenfalls als bosniakisch."

- ↑ Gruber 2008, p. 142. "Migration to Shkodra was mostly from the villages to the south-east of the city and from the cities of Podgorica and Ulcinj in Montenegro. This was connected to the independence of Montenegro from the Ottoman Empire in the year 1878 and the acquisition of additional territories, e.g. Ulcinj in 1881 (Ippen, 1907, p. 3)."

- ↑ Steinke & Ylli 2013, p. 9. "Am östlichen Ufer des Shkodrasees gibt es heute auf dem Gebiet von Vraka vier Dörfer, in denen ein Teil der Bewohner eine montenegrinische Mundart spricht. Es handelt sich dabei um die Ortschaften Boriçi i Madh (Borić Veli), Boriçi i Vogël (Borić Mali/Borić Stari/Borić Vezirov), Gril (Grilj) und Omaraj (Omara), die verwaltungstechnisch Teil der Gemeinde Gruemira in der Region Malësia e Madhe sind. Ferner zählen zu dieser Gruppe noch die Dörfer Shtoji i Ri und Shtoji i Vjetër in der Gemeinde Rrethinat und weiter nordwestlich von Koplik das Dorf Kamica (Kamenica), das zur Gemeinde Qendër in der Region Malësia e Madhe gehört. Desgleichen wohnen vereinzelt in der Stadt sowie im Kreis Shkodra weitere Sprecher der montenegrinischen Mundart. Nach ihrer Konfession unterscheidet man zwei Gruppen, d.h. orthodoxe mid muslimische Slavophone. Die erste, kleinere Gruppe wohnt in Boriçi i Vogël, Gril, Omaraj und Kamica, die zweite, größere Gruppe in Boriçi i Madh und in Shtoj. Unter den in Shkodra wohnenden Slavophonen sind beide Konfessionen vertreten... Die Muslime bezeichnen sich gemeinhin als Podgoričani ‘Zuwanderer aus Podgorica’ und kommen aus Zeta, Podgorica, Tuzi usw."; p. 19. "Ohne genaue Quellenangabe bringt ŠĆEPANOVIĆ (1991: 716–717) folgende ,,aktuelle" Zahlen:... Veliki (Mladi) Borić 112 Familien, davon 86 podgoričanski, 6 crnogorski und 20 albanische Familien. STOPPEL (2012: 28) sagt Folgendes über die Montenegriner in Albanien: ,,hierbei handelt es sich um (nach Erhebungen des Helsinki-Komitees von 1999 geschätzt,, etwa 1800–2000 serbisch-sprachige Personen in Raum des Shkodra-Sees und im nördlichen Berggrenzland zu Montenegro, die 1989 eher symbolisch mit ca. 100 Personen angegeben und nach 1991 zunächst überwiegend nach Jugoslawien übergewechselt waren". p. 20. "Außer in Boriçi i Madh und auch in Shtoj, wo die Slavophonen eine kompakte Gruppe innerhalb des jeweiligen Ortes bilden, sind sie in anderen Dorfern zahlenmäßig bedeutunglos geworden."; p. 131. "In Shtoj i Vjetër leben heute ungefähr 30 und in Shtoj i Ri 17 muslimische Familien, d.h Podgoričaner."

- 1 2 3 4 Endresen 2011, pp. 40–43.

- ↑ Misha 2002, p. 43.

- ↑ Endresen 2010, p. 249.

- ↑ Kostov 2010, p. 40.

- 1 2 Skendi 1967a, pp. 181–189.

- ↑ Skoulidas 2013. para. 19, 26.

- ↑ Shaw & Shaw 1977, p. 254.

- ↑ Takeyh & Gvosdev 2004, p. 80.

- 1 2 Gawrych 2006, pp. 140–169.

- ↑ Skendi 1967a, p. 143.

- ↑ Merdjanova 2013, p. 41.

- ↑ Petrovich 2000, p. 1357.

- ↑ Stoyanov 2012, p. 186.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kokolakis 2003, p. 53."Με εξαίρεση τις ολιγομελείς κοινότητες των παλιών Ρωμανιωτών Εβραίων της Αρτας και των Ιωαννίνων, και την ακόμη ολιγομελέστερη ομάδα των Καθολικών της Αυλώνας, οι κάτοικοι της Ηπείρου χωρίζονται με το κριτήριο της θρησκείας σε δύο μεγάλες ομάδες, σε Ορθόδοξους και σε Μουσουλμάνους. [With the exception of a few members of the old communities such as Romaniote Jews of Arta and Ioannina, and even small groups of Catholics in Vlora, the residents of Epirus were separated by the criterion of religion into two major groups, the Orthodox and Muslims.]"; p. 54. "Η μουσουλμανική κοινότητα της Ηπείρου, με εξαίρεση τους μικρούς αστικούς πληθυσμούς των νότιων ελληνόφωνων περιοχών, τους οποίους προαναφέραμε, και τις δύο με τρεις χιλιάδες διεσπαρμένους «Τουρκόγυφτους», απαρτιζόταν ολοκληρωτικά από αλβανόφωνους, και στα τέλη της Τουρκοκρατίας κάλυπτε τα 3/4 περίπου του πληθυσμού των αλβανόφωνων περιοχών και περισσότερο από το 40% του συνόλου. [The Muslim community in Epirus, with the exception of small urban populations of the southern Greek-speaking areas, which we mentioned, and 2-3000 dispersed "Muslim Romani", consisted entirely of Albanian speakers, and in the late Ottoman period covered approximately 3/4 of population ethnic Albanian speaking areas and more than 40% of the total area."; pp.55–56. "Σ' αυτά τα μέρη οι μουσουλμανικές κοινότητες, όταν υπήρχαν, περιορίζονταν στο συμπαγή πληθυσμό ορισμένων πόλεων και κωμοπόλεων (Αργυρόκαστρο, Λιμπόχοβο, Λεσκοβίκι, Δέλβινο, Παραμυθιά). [In these parts of the Muslim communities, where present, were limited to compact population of certain towns and cities (Gjirokastër, Libohovë, Leskovik, Delvinë, Paramythia).]", pp. 370, 374.

- ↑ Stoppel 2001, pp. 9–10."In den südlichen Landesteilen hielten sich Muslime und Orthodoxe stets in etwa die Waage: So standen sich zB 1908 in den Bezirken (damals türkischen Sandschaks) Korca und Gjirokastro 95.000 Muslime und 128.000 Orthodoxe gegenüber, während 1923 das Verhältnis 109.000 zu 114.000 und 1927 116.000 zu 112.000 betrug. [In the southern parts of the country, Muslims and Orthodox were broadly always balanced: Thus, for example in 1908 were in the districts (then Turkish Sanjaks) Korçë and Gjirokastër 95,000 Muslims and in contrast to 128,000 Orthodox, while in 1923 the ratio of 109,000 to 114,000 and 1927 116,000 to 112,000 it had amounted too.]"

- ↑ Baltsiotis 2011. para. 14. "The fact that the Christian communities within the territory which was claimed by Greece from the mid 19th century until the year 1946, known after 1913 as Northern Epirus, spoke Albanian, Greek and Aromanian (Vlach), was dealt with by the adoption of two different policies by Greek state institutions. The first policy was to take measures to hide the language(s) the population spoke, as we have seen in the case of "Southern Epirus". The second was to put forth the argument that the language used by the population had no relation to their national affiliation... As we will discuss below, under the prevalent ideology in Greece at the time every Orthodox Christian was considered Greek, and conversely after 1913, when the territory which from then onwards was called "Northern Epirus" in Greece was ceded to Albania, every Muslim of that area was considered Albanian."

- ↑ Kokolakis 2003, p. 56. "Η διαδικασία αυτή του εξελληνισμού των ορθόδοξων περιοχών, λειτουργώντας αντίστροφα προς εκείνη του εξισλαμισμού, επιταχύνει την ταύτιση του αλβανικού στοιχείου με το μουσουλμανισμό, στοιχείο που θ' αποβεί αποφασιστικό στην εξέλιξη των εθνικιστικών συγκρούσεων του τέλους του 19ου αιώνα. [This process of Hellenization of Orthodox areas, operating in reverse to that of Islamization, accelerated the identification of the Albanian element with Islam, an element that will prove decisive in the evolution of nationalist conflicts during the 19th century]"; p. 84. "Κύριος εχθρός του ελληνισμού από τη δεκαετία του 1880 και ύστερα ήταν η αλβανική ιδέα, που αργά μα σταθερά απομάκρυνε την πιθανότητα μιας σοβαρής ελληνοαλβανικής συνεργασίας και καθιστούσε αναπόφευκτο το μελλοντικό διαμελισμό της Ηπείρου. [The main enemy of Hellenism from the 1880s onwards was the Albanian idea, slowly but firmly dismissed the possibility of serious Greek-Albanian cooperation and rendered inevitable the future dismemberment of Epirus.]"

- 1 2 Vickers 2011, pp. 60–61. "The Greeks too sought to curtail the spread of nationalism amongst the southern Orthodox Albanians, not only in Albania but also in the Albanian colonies in America."

- ↑ Skendi 1967a, pp. 175–176, 179.

- 1 2 Kokolakis 2003, p. 91. "Περιορίζοντας τις αρχικές του ισλαμιστικές εξάρσεις, το αλβανικό εθνικιστικό κίνημα εξασφάλισε την πολιτική προστασία των δύο ισχυρών δυνάμεων της Αδριατικής, της Ιταλίας και της Αυστρίας, που δήλωναν έτοιμες να κάνουν ό,τι μπορούσαν για να σώσουν τα Βαλκάνια από την απειλή του Πανσλαβισμού και από την αγγλογαλλική κηδεμονία που υποτίθεται ότι θα αντιπροσώπευε η επέκταση της Ελλάδας. Η διάδοση των αλβανικών ιδεών στο χριστιανικό πληθυσμό άρχισε να γίνεται ορατή και να ανησυχεί ιδιαίτερα την Ελλάδα." "[By limiting the Islamic character, the Albanian nationalist movement secured civil protection from two powerful forces in the Adriatic, Italy and Austria, which was ready to do what they could to save the Balkans from the threat of Pan-Slavism and the Anglo French tutelage that is supposed to represent its extension through Greece. The dissemination of ideas in Albanian Christian population started to become visible and very concerning to Greece]."

- 1 2 Gawrych 2006, pp. 22–28.

- ↑ Hart 1999, p. 199.

- 1 2 3 Gawrych 2006, pp. 28–34.

- 1 2 3 Duijzings 2000, pp. 162–163.

- ↑ Clayer 2003, pp. 2–5, 37. "Between 1942 (date of the last census taking into account the denominational belonging) or 1967 (date of religion's banning) and 2001, the geographical distribution of the religious communities in Albania has strongly changed. The reasons are first demographic: groups of population, mainly from Southern Albania, came to urban settlements of central Albania in favour of the institution of the Communist regime, during the 1970s and 1980s, Northern Catholic and Sunni Muslim areas have certainly experienced a higher growth rate than Southern Orthodox areas. Since 1990, there were very important population movements, from rural and mountain areas towards the cities (especially in central Albania, i.e. Tirana and Durrës), and from Albania towards Greece, Italy and many other countries".

- ↑ Odile 1990, p. 2.

- 1 2 Doja 2008, pp. 58–59.

- ↑ Doja 2008, p. 59.

- 1 2 3 Nezir-Akmese 2005, p. 96.

- 1 2 Poulton 1995, p. 66.

- ↑ Shaw & Shaw 1977, p. 287.

- 1 2 Skendi 1967a, pp. 370–378.

- 1 2 Duijzings 2000, p. 163.

- 1 2 Gawrych 2006, pp. 182.

- ↑ Massicard 2013, p. 18.

- 1 2 Nezir-Akmese 2005, p. 97.

- ↑ Puto & Maurizio 2015, p. 183."Nineteenth-century Albanianism was not by any means a separatist project based on the desire to break with the Ottoman Empire and to create a nationstate. In its essence Albanian nationalism was a reaction to the gradual disintegration of the Ottoman Empire and a response to the threats posed by Christian and Balkan national movements to a population that was predominantly Muslim."

- ↑ Shaw & Shaw 1977, p. 288.

- ↑ Gawrych 2006, pp. 177–179.

- ↑ Gawrych 2006, pp. 190–196.

- ↑ Bloxham 2005, p. 60.

Sources

- Baltsiotis, Lambros (2011). "The Muslim Chams of Northwestern Greece: The grounds for the expulsion of a "non-existent" minority community". European Journal of Turkish Studies. 12.

- Bloxham, Donald (2005). The Great Game of Genocide: Imperialism, Nationalism, and the Destruction of the Ottoman Armenians. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-150044-2.

- Blumi, Isa (2011). Reinstating the Ottomans, Alternative Balkan Modernities: 1800–1912. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 978-0-230-11908-6.

- Clayer, Nathalie (2003). "God in the 'Land of the Mercedes.' The Religious Communities in Albania since 1990". In Jordan, Peter; Kaser, Karl; Lukan, Walter (eds.). Albanien: Geographie – historische Anthropologie – Geschichte – Kultur – postkommunistische Transformation [Albania: Geography – Historical Anthropology – History – Culture – postcommunist transformation]. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. pp. 277–314. ISBN 978-3-631-39416-8.

- Doja, Albert (2008). "Instrumental Borders of Gender and Religious Conversion in the Balkans". Religion, State & Society. 36 (1): 55–63. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.366.8652. doi:10.1080/09637490701809738.

- Duijzings, Gerlachlus (2000). Religion and the politics of identity in Kosovo. London: Hurst & Company. ISBN 978-1-85065-431-5.

- Endresen, Cecilie (2010). ""Do not look to church and mosque"? Albania's post-Communist clergy on nation and religion". In Schmitt, Oliver Jens (ed.). Religion und Kultur im albanischsprachigen Südosteuropa. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. pp. 233–258. ISBN 978-3-631-60295-9.

- Endresen, Cecilie (2011). "Diverging images of the Ottoman legacy in Albania". In Hartmuth, Maximilian (ed.). Images of Imperial Legacy: Modern Discourses on the Social and Cultural Impact of Ottoman and Habsburg Rule in Southeast Europe. Berlin: Lit Verlag. pp. 37–52. ISBN 978-3-643-10850-0.

- Hart, Laurie Kain (1999). "Culture, Civilization, and Demarcation at the Northwest Borders of Greece". American Ethnologist. 26 (1): 196–220. doi:10.1525/ae.1999.26.1.196. JSTOR 647505.

- Gawrych, George (2006). The Crescent and the Eagle: Ottoman Rule, Islam and the Albanians, 1874-1913. London: IB Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-287-5.

- Gruber, Siegfried (2008). "Household structures in urban Albania in 1918". The History of the Family. 13 (2): 138–151. doi:10.1016/j.hisfam.2008.05.002.

- Jelavich, Barbara (1983). History of the Balkans. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-27459-3.

- Karpat, Kemal (2001). The Politicization of Islam: Reconstructing Identity, State, Faith, and Community in the Late Ottoman State. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-028576-0.

- Kokolakis, Mihalis (2003). Το ύστερο Γιαννιώτικο Πασαλίκι: χώρος, διοίκηση και πληθυσμός στην τουρκοκρατούμενη Ηπειρο (1820–1913) [The late Pashalik of Ioannina: Space, administration and population in Ottoman ruled Epirus (1820–1913)]. Athens: EIE-ΚΝΕ. ISBN 978-960-7916-11-2.

- Kostov, Chris (2010). Contested Ethnic Identity: The Case of Macedonian Immigrants in Toronto 1900-1996. Oxford: Peter Lang. ISBN 978-3-0343-0196-1.

- Massicard, Élise (2013). The Alevis in Turkey and Europe: Identity and Managing Territorial Diversity. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-66796-8.

- Megalommatis, M. Cosmas (1994). Turkish-Greek Relations and the Balkans: A Historian's Evaluation of Today's Problems. Cyprus Foundation.

- Mentzel, Peter (2000). "Introduction: Identity, confessionalism, and nationalism". Nationalities Papers. 28 (1): 7–11. doi:10.1080/00905990050002425.

- Merdjanova, Ina (2013). Rediscovering the Umma: Muslims in the Balkans Between Nationalism and Transnationalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-046250-5.

- Misha, Piro (2002). "Invention of a Nationalism: Myth and Amnesia". In Schwanders-Sievers, Stephanie; Fischer, Bernd J. (eds.). Albanian Identities: Myth and History. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 33–48. ISBN 9780253341891.

- Nezir-Akmese, Handan (2005). The Birth of Modern Turkey: The Ottoman Military and the March to WWI. London: IB Tauris. ISBN 978-1-85043-797-0.

- Nikolopoulou, Kalliopi (2013). Tragically Speaking: On the Use and Abuse of Theory for Life. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 9780803244870.

- Nitsiakos, Vassilis (2010). On the Border: Transborder Mobility, Ethnic Groups and Boundaries Along the Albanian-Greek Frontier. Berlin: LIT Verlag. ISBN 978-3-643-10793-0.

- Odile, Daniel (1990). "The historical role of the Muslim community in Albania". Central Asian Survey. 9 (3): 1–28. doi:10.1080/02634939008400712.

- Petrovich, Michael B. (2000). "Religion and ethnicity in Eastern Europe". In Hutchinson, John; Smith, Anthony D. (eds.). Nationalism: Critical concepts in political science. London: Psychology Press. pp. 1356–1381. ISBN 978-0-415-20109-4.

- Poulton, Hugh (1995). Who are the Macedonians?. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 9781850652380.

- Puto, Artan; Maurizio, Isabella (2015). "From Southern Italy to Istanbul: Trajectories of Albanian Nationalism in the Writings of Girolamo de Rada and Shemseddin Sami Frashëri, ca. 1848–1903". In Maurizio, Isabella; Zanou, Konstantina (eds.). Mediterranean Diasporas: Politics and Ideas in the Long 19th Century. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4725-7666-8.

- Shaw, Stanford J.; Shaw, Ezel Kural (1977). History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey: Volume 2, Reform, Revolution, and Republic: The Rise of Modern Turkey 1808–1975. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29166-8.

- Skendi, Stavro (1967a). The Albanian national awakening. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-4776-1.

- Skoulidas, Elias (2013). "The Albanian Greek-Orthodox Intellectuals: Aspects of their Discourse between Albanian and Greek National Narratives (late 19th - early 20th centuries)". Hronos. 7. Archived from the original on 2019-09-23. Retrieved 2016-11-19.

- Steinke, Klaus; Ylli, Xhelal (2013). Die slavischen Minderheiten in Albanien (SMA). 4. Teil: Vraka – Borakaj. Munich: Verlag Otto Sagner. ISBN 978-3-86688-363-5.

- Stoyanov, Yuri (2012). "Contested Post-Ottoman Alevi and Bektashi Identities in the Balkans and their Shi'ite Component". In Ridgeon, Lloyd VJ (ed.). Shi'i Islam and Identity: Religion, Politics and Change in the Global Muslim Community. New York: IB Tauris. pp. 170–209. ISBN 978-1-84885-649-3.

- Stoppel, Wolfgang (2001). Minderheitenschutz im östlichen Europa (Albanien) [Protection of minorities in Eastern Europe (Albania)] (PDF) (Report). Cologne: Universität Köln. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2016-11-19.

- Takeyh, Ray; Gvosdev, Nikolas K. (2004). The receding shadow of the prophet: The rise and fall of radical political Islam. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-97628-6.

- Tošić, Jelena (2015). "City of the 'calm': Vernacular mobility and genealogies of urbanity in a southeast European borderland". Southeast European and Black Sea Studies. 15 (3): 391–408. doi:10.1080/14683857.2015.1091182.

- Vickers, Miranda (2011). The Albanians: a modern history. London: IB Tauris. ISBN 978-0-85773-655-0.