| Iraqi Ground Forces | |

|---|---|

| القوات البرية العراقية | |

Iraqi Ground Forces' insignia | |

| Founded | 1921 |

| Country | |

| Type | Army |

| Role | Ground warfare |

| Size | "190,000 Army/Aviation Command/Special Forces" (2023)[1] est. 180,000, inc CTS[2] |

| Part of | Iraqi Armed Forces |

| Garrison/HQ | Baghdad |

| Colors | Red |

| Anniversaries | Army Day (January 6)[3] |

| Equipment | List of current equipment of the Iraqi Ground Forces |

| Engagements |

|

| Decorations | Military awards and decorations |

| Commanders | |

| President of Iraq | Abdul Latif Rashid |

| Prime Minister of Iraq | Mohammed Shia' Al Sudani |

| Insignia | |

| Identification symbol |  |

| Flag |  |

The Iraqi Ground Forces (Arabic: القوات البرية العراقية), or the Iraqi Army (Arabic: الجيش العراقي), is the ground force component of the Iraqi Armed Forces. It was formerly known as the Royal Iraqi Army up until the coup of July 1958.

The Iraqi Army in its modern form was first created by the United Kingdom during the inter-war period of de facto British control of Mandatory Iraq. Following the invasion of Iraq by U.S. forces in 2003, the Iraqi Army was rebuilt along U.S. lines with enormous amounts of U.S. military assistance at every level. Because of the Iraqi insurgency that began shortly after the invasion, the Iraqi Army was later designed to initially be a counter-insurgency force.[4][5] With the withdrawal of U.S. troops in 2010, Iraqi forces have assumed full responsibility for their own security.[6] A New York Times article suggested that, between 2004 and 2014, the U.S. had provided the Iraqi Army with $25 billion in training and equipment in addition to an even larger sum from the Iraqi treasury.[7]

The Army extensively collaborated with Iraqi Popular Mobilization Forces during anti-ISIL operations.

History

The modern Iraqi armed forces were established by the United Kingdom during their mandate over Iraq after World War I.[8] Before that, from 1533 to 1918, Iraq was under the rule of the Ottoman Empire and fought as part of the Military of the Ottoman Empire. At first, the British created the Iraq Levies, comprising several battalions of troops whose main mission was to garrison the bases of the Royal Air Force (RAF) with which London controlled Iraq. The Levies were adequate for their intended mission of defending airfields of RAF Iraq Command, but the threat of war with the newly forming Republic of Turkey forced the British to expand Iraq's indigenous military forces.[8]

Ankara claimed the Ottoman vilayet of Mosul as part of their country, during their resistance to the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire. This province corresponds to the northern third of modern Iraq, mainly Iraqi Kurdistan, and includes the rich oilfields of Kirkuk.[8] In 1920, Turkish troops penetrated into Iraqi Kurdistan and forced out small British garrisons out of as-Sulaymaniyyah and Rawanduz in eastern Kurdistan. This led the British to form the Iraqi Army on 6 January 1921 (later to be marked as Iraqi Army Day),[9] followed by the Iraqi Air Force in 1927. The British recruited former Ottoman officers to man junior and middle ranks of the new Iraqi officer corps, with senior commands being manned by British officers, as well as most training positions.[8]

The Musa al-Kadhim Brigade consisted of ex-Iraqi-Ottoman officers, whose barracks were located in Kadhimyah. The United Kingdom provided support and training to the Iraqi Army and the Iraqi Air Force through a small military mission based in Baghdad;[10] providing weapons and training to defeat the anticipated Turkish invasion of northern Iraq.

Royal Iraqi Army

In August 1921, the British installed Hashemite King Faisal I as the client ruler of Mandatory Iraq. Faisal had been forced out as the King of Syria by the French in the aftermath of the Franco-Syrian War in 1920. Likewise, British authorities selected Sunni Arab elites from the region for appointments to government and ministry offices in Iraq. The British and the Iraqis formalized the relationship between the two nations with the Anglo-Iraqi Treaty of 1922. With Faisal's ascension to the throne, the Iraqi Army became the Royal Iraqi Army (RIrA).

In 1922, the army totalled 3,618 men. This was well below the 6,000 men requested by the Iraqi monarchy and even less than the limit set by the British of 4,500. Unattractive salaries hindered early recruiting efforts. At this time, the United Kingdom maintained the right to levy local forces like the British-officered Iraq Levies which were under direct British control. With a strength of 4,984 men, the Iraq Levies outnumbered the army.

In 1924, the army grew to 5,772 men and, by the following year, had grown even more to reach 7,500 men - maintaining this size until 1933. The force's order of battle consisted of:[11]

- Six infantry battalions,

- Three cavalry regiments,

- Two mountain regiments,

- One field artillery battery.

By the late 1920s, the threat of Turkish attack diminished, with the Iraqi army refocusing on new, internal missions. While the British command still worried about both Turkish and Persian encroachment on the Iraqi territory - as both of these states were considerably more cohesive and with superior armies -, the new focus shifted towards internal security against centrifugal forces menacing to breakdown the country.

Those threats to the integrity of the nascent Iraqi state were separatist revolts by the Kurds and by the powerful tribes of western and southern Iraq.[8] The British concluded the Iraqi army was not capable of handling either the Turks or the Persians, with the RAF (supported by the Iraq Levies) shouldering the full responsibility for external defense.[12] Henceforth, the Iraqi army was increasingly relegated to internal security duties. Nevertheless, the army enjoyed considerable prestige, with the country's elites seeing the army as a national consolidating force:[12]

- A strong army ensured Sunni dominance over the Shia majority;

- Said strong army would allow Baghdad to control the independent tribes who resisted centralization;

- The army would create a national identity.

With the majority under control, the unruly tribes kept in line and a national identity across the heterogeneous population, the army would serve as a modernizing and socializing force that would help to weld together the backward Ottoman vilayets into a modern, unified Iraqi nation.[13]

There were doubts about the army's actual capabilities, however. In 1928, the number of British officers commanding Iraqi units was increased because Iraqi officers were slow to adapt to modern warfare.[14] The army's first real test occurred in 1931, when Kurdish leader Ahmed Barzani unified a number of Kurdish tribes and rose up in open revolt. Iraqi army units were badly mauled by tribesmen under Shaykhs Mahmud and Mustafa Barzani. The Iraqi army's dismal performance did not impress, and the situation required the intervention of British troops to restore order.[12]

In 1932, the Kingdom of Iraq was granted official independence.[12] This was in accordance with the Anglo-Iraqi Treaty of 1930, whereby the United Kingdom would end its official mandate on the condition that the Iraqi government would allow British advisers to take part in government affairs, allow British military bases to remain, and a requirement that Iraq assist the United Kingdom in wartime.[15]

The new state was weak and the regime survived for only four years, when it was toppled in a coup d'état in 1936. Upon achieving independence in 1932, political tensions arose over the continued British presence in Iraq, with Iraq's government and politicians split between those considered pro-British and those who were considered anti-British. The pro-British faction was represented by politicians such as Nuri as-Said who did not oppose a continued British presence. The anti-British faction was represented by politicians such as Rashid Ali al-Gaylani who demanded that remaining British influence in the country be removed.[15] In 1936, General Bakr Sidqi, who had won a reputation from suppressing tribal revolts (and also responsible for the ruthless Simele massacre), was named Chief of the General Staff and successfully pressured King Ghazi bin Faisal to demand that the Cabinet resign.[16] From that year to 1941, five army coups occurred during each year led by the chief officers of the army against the government to pressure the government to concede to Army demands.[15]

1941 coup

In early April 1941, during World War II, Rashid Ali al-Gaylani and members of the anti-British "Golden Square" launched a coup d'état against the current government. Prime Minister Taha al-Hashimi resigned and Rashid Ali al-Gaylani took his place as Prime Minister. Rashid Ali also proclaimed himself chief of a "National Defence Government." He did not overthrow the monarchy, but installed a more compliant regent. He also attempted to restrict the rights of the British which were granted them under the 1930 treaty.

The Golden Square was commanded by the "Four Colonels":[17]

- Colonel Salah ed-Din es-Sabbagh, commander of the 3rd Infantry Division;

- Colonel Kamal Shahib, commander of the 1st Infantry Division;

- Colonel Fahmi Said, commander of the Independent Mechanized Brigade;

- Colonel Mahmud Salman, chief of the Air Force.

Although Iraq was nominally independent, Britain de facto still governed the country, exercising veto over Iraqi foreign and national security policy. The Iraqi high command saw the opportunity to rid themselves of their colonial master when Britain saw itself in a vulnerable position against Nazi Germany. The golpistas were supported by the pro-Nazi and anti-Jewish Grand Mufti of Jerusalem Haj Amin al-Husseini, the German ambassador Fritz Grobba and Arab guerrilla leader Fawzi al-Qawuqji.[17]

On April 30, Iraqi Army units took the high ground to the south of RAF Habbaniya. An Iraqi envoy was sent to demand that no movements, either ground or air, were to take place from the base. The British refused the demand and then themselves demanded that the Iraqi units leave the area at once. In addition, the British landed forces at Basra and the Iraqis demanded that these forces be removed.

At 0500 hours on 2 May 1941, the Anglo-Iraqi War broke out between the British and Rashid Ali's new government when the British at RAF Habbaniya launched air strikes against the Iraqis. By this time, the army had grown significantly. It had four infantry divisions with some 60,000 men.[18][10] At full strength, each division had three infantry brigades (3 battalions each) plus supporting units - including artillery brigades.[10] The Iraqi 1st and 3rd Divisions were stationed in Baghdad. The 2nd Division was stationed in Kirkuk, and the 4th Division was in Al Diwaniyah, on the main rail line from Baghdad to Basra.

Also based within Baghdad was the Independent Mechanized Brigade composed of:[19]

- Light Tank Company (Fiat L3/35 tankettes);

- Armoured car company (14 Vickers Crossley);

- Two battalions of "mechanized" infantry;

- One "mechanized" machine-gun company;

- One "mechanized" artillery brigade.

All these "mechanized" infantry units were transported by trucks. The authorized manpower of the Iraqi Infantry Brigades at full strength were of 26 officers and 820 other ranks, 46 Bren light machine guns; 8 Vickers heavy machine guns (in two platoons of 4 MGs each) and 4 anti-air Lewis guns.[19]

Hostilities between the British and the Iraqis lasted from 2 May to 30 May 1941. The German government despatched an aviation unit, Fliegerführer Irak, and Italy send limited assistance, but both were too late and far from adequate. Britain pulled together a small force from its armies in the Levant, which handily defeated the much larger but thoroughly incompetent Iraqi army and air force,[12] marched on Baghdad and ousted the military commanders (that were sentenced to death by hanging) and their prime minister, Rashid Ali al-Gaylani. In their place the British re-installed Nuri al-Said, which dominated the politics of Iraq until the overthrow of the monarchy and his assassination in 1958. Nuri al-Said pursued a largely pro-western policy during this period.[15] The army was not disbanded, however. Instead, it was maintained to hinder possible German offensive actions via the southern parts of the Soviet Union.

1948 Arab–Israeli War

The 1948 Arab–Israeli War was the first combat experience of independent Iraqi forces after the Second World War, and its first war outside its territory. Baghdad joined the Arab states in their opposition to the creation of the Jewish national homeland in Palestine, and in May 1948 sent a sizeable force to help crush the recently independent state of Israel. The Iraqi Army by then boasted 21,000 men in 12 brigades, with the Royal Iraqi Air Force having a force of 100 aircraft (mostly British);[20] sending initially 5,000 men in four infantry brigades and an armoured battalion with corresponding support personnel. Iraq continuously sent reinforcements to its expeditionary force, peaking at 15–18,000 men.[20] Iraq also contributed 2,500 volunteers to the Arab Liberation Army (ALA), an irregular force commanded by the former Ottoman officer Fawzi al-Qawuqji.[21][22]

Before the Arab League resolution to attack Israel, the ALA was used to fight the Jewish settlements, launching its first offensive in February 1948.[23]> With a force around 6,000 men it was mainly organized by Syria, with 2,500 Syrian volunteers providing a third of the force,[23] with another third provided by the Iraqis; the rest being Arab Palestinians, Lebanese and other Muslims. Its commander Fawzi was also Syrian, with the costs being paid by members of the Arab League.

Iraqi forces received their baptism of fire with the ALA defending Zefat in April and May 1948.[20] A force of 600 Syrian and Iraqi ALA irregulars were sent to defend this key town, which controlled access between the Huleh Valley and the Sea of Galilee (Lake Kinneret). Zefat was protected by two police forts built into the rock of the hills, forming a formidable position; and also a priority target for the Haganah.[20] The strength of the natural position allowed the ALA, together with some local Arab militiamen, to defeat two Israeli attacks by elements of the Golani Brigade in April.[20] The Israelis brought a new battalion in May and immediately took one of the forts. With the arrival of another battalion, the Israelis assaulted the town itself under cover of mortar fire but the Arabs succeeded in forcing back repeated assaults. Four days after the first attack in the town, the Israelis attacked at night under cover of a rainstorm and surprised the defenders.[20] The Arabs resisted fiercely and forced the Israelis to fight house to house but ultimately were ejected from the town. After this defeat, the Arab force gave up the last police fort without a fight and withdrew.[20]

On 25 April, the Israeli Irgun Zvi Leumi assaulted the Arab town of Jaffa with 600 men,[20] initiating Operation Hametz, but were stopped cold by a similar-sized force of Iraqi ALA irregulars in house to house combat; forcing the Irgun to ask for help from the Haganah after two days of fighting.[20] Heavy fighting continued with British units intervening on behalf of the Arabs and losing a number of tanks against Irgun ambushes. Jaffa would fall to the Israelis on 13 May.

On 29 April, units of the élite Palmach assaulted positions on the Katamon Ridge south of Jerusalem held by Iraqi ALA irregulars.[24] The Palmach secured a foothold with a surprise night attack that took the monastery dominating the ridge. In the morning the Iraqis launched a furious counterattack that evolved into an extremely tough fight, but eventually the Iraqis called off their attack to regroup; at noon the Israelis were reinforced by another battalion.[25] This new balance of combat power lead the exhausted and bloodied Iraqis to decide they did not possess the strength to dislodge the Israelis, and they retired from the field. After these defeats, the ALA took several months to resume operations, but by then most of its Iraqi contingent had joined the main Iraqi expeditionary force that had arrived in northern Samaria.[25]

The first Iraqi forces of the expeditionary force reached Transjordan in early April 1948, with one infantry brigade and a supporting armoured battalion under the command of General Nur ad-Din Mahmud.[25] On 15 May, Iraqi engineers built a pontoon bridge across the Jordan River, allowing the combat units to cross into Palestine. Over 3,000 Iraqi soldiers with armor and air support were unable to defeat less than 50 lightly armed Jewish defenders. After the crossing, the Iraqis immediately launched a frontal assault against the Israeli settlement of Gesher, only to be quickly driven back.[25] The Iraq army tried again the next day, with their armour attacking from the south and their infantry from the north. The double envelopment was poorly implemented - lacking infantry-tank coordination - which left the Israelis with the breathing space to redeploy their small force along internal lines and defeat each attack in turn.[25] The Iraqis launched clumsy frontal assaults, with the unprotected tanks and armoured cars being easily destroyed by AT hunter-killer teams. Several days later, Mahmud tried to attack another Jewish settlement in the same area, but the troops did not scout their route properly and got ambushed before they could even reach the target settlement. These defeats convinced the Iraqi army to abandon this sector of the front and try their luck elsewhere.[25]

The expeditionary force moved into the Nablus–Jenin–Tulkarm strategic triangle in May,[25] that being the West Bank region of northern Samaria. That was a key sector for the Arab war effort because it was the ideal jumping point for an attack westward against Haifa to split the narrow Israeli corridor along the Mediterranean coast (which was only 15 km wide) and break the country in half; it would also guard the right flank of the Transjordanian Arab Legion, which was concentrated to the south, around the Jerusalem corridor. Previously, this sector had been held by elements of the ALA that were too weak to pose much of a threat to the Israelis, but the arrival of the powerful Iraqi force led the Arabs to believe they would be able to cut Israel in two. While setting down the Iraqis were reinforced by another infantry brigade and another armoured battalion. The build-up continued steadily, with the expeditionary force reaching seven or eight infantry brigades, an armoured brigade and three air force squadrons.[26][27]

In late May, the Haganah launched a major assault against the Arab Legion's positions in the Latrun police fort on the Jerusalem-Tel Aviv road.[28] The Israeli attacks were extremely heavy, prompting the Jordanians to plead with the Iraqis to attack to draw off Israeli forces from Latrum; either northwest toward Haifa or north into Galilee. The Iraqi army was slow to respond and only launched two half-hearted attacks that were easily defeated by local Israeli forces.[28] Nevertheless, Haganah commanders pinpointed the Iraqi presence, by its size and location, to be a dangerous threat in a possible offensive. The Israelis decided to launch a preemptive attack south from Galilee to take Jenin, and possibly Nablus, and cut the Iraqi supply lines across the Jordan River. To achieve that the Israelis would employ three brigades: Alexandroni, Carmeli and Golani.[28]

At the same time, the Iraqis were planning the exact offensive the Israelis feared. As the first truce was approaching, the general headquarters of the Arab forces in Zarqaa ordered the commander of the Iraqi forces in Shechem to take control of a number of Israeli settlements in order to strengthen their position at the ceasefire talks. It was decided to take control of the port of Netanya, as it was considered an essential target and an important commercial center, and it would split Israeli communications between north and south - thus denying the Israelis movement between their internal lines.

The Israeli preemptive offensive began on the night of 28 May and caught the Iraqis by surprise. The plan called for the Alexandroni Brigade to make a diversionary attack against Tulkarm, while the Golanis would drive south toward Jenin; holding the high ground to the north. Then, the Carmeli Brigade would exploit the success passing though the Golani's lines and seize the town itself. The Golani attack to the north made good progress - despite the Alexandronis failing to execute their feint - and took a series of hills, villages and police posts en route to Nablus. The Iraqi defenders responded slowly and Israeli infantry repreatedly occupied key positions before Iraqi armoured car battalions arrived. The Golanis outmaneuvered the Iraqi forces in a series of skirmishes, outflanking and mauling them before they could retreat on multiple occasions. The Iraqis kept launching determined attacks against positions already occupied by the Israelis who, by then dug in, easily threw them back. The Israelis were now in a good position to assault Jenin.[29]

Iraqi reinforcements kept arriving north and when the Carmeli Brigade took over the spearhead of the Israeli attack, it began to run into them. An Iraqi brigade had fortified itself in the city by the time the Israelis reached Jenin on 3 June, and on the two hills dominating the city from the south. The Carmelis launched a clumsy frontal night assault but still managed to push off the Iraqis off both hills in a protracted battle. The next morning the Iraqis brought up fresh forces and counterattacked with a reinforced battalion, with artillery support and inaccurate (albeit helpful) airstrikes, that eventually retook the southwestern hill from the exhausted Israelis. A fierce battle developed for control of Jenin itself, and although in a continuous stalemate, the Iraqi commander kept feeding fresh troops into the fight until the Israelis concluded that holding the town was not worth the price in casualties and pulled back to the hills north of Jenin.[30] They suffered heavy casualties in the Israeli attack on Jenin, but they managed to hold on to their positions and could absorb the losses. Overall, the Iraqi troops distinguished themselves at Jenin, even impressing their Israeli opponents.[31] Active Iraqi involvement in the war effectively ended at this point.

By the beginning of 1951, British General Sir Brian Robertson, Commander-in-Chief, Middle East Land Forces, was keen to upgrade the Iraqi Army as part of a wider effort to defend against a feared Soviet invasion in the event of war. A British MELF advisory team was dispatched there in November–December 1950. The team estimated that Iraqi's forces of the time, two divisions and a mechanized brigade, but deemed ill-equipped and 'not up to establishment' [full strength] would have to be increased, and a total of four divisions, three additional brigades, and more artillery units would be needed. The shortage of trained technical personnel was 'grave,' and the Iraqis were 'incapable of maintaining even the limited equipment already in their possession.'[32] In January 1951 the British Military Attaché deemed that the Iraqi Army's ability '..to wage modern warfare against a first class enemy is practically nil ... in its present state, the Iraqi army would be entirely incapable of remaining an effective force for more than ten hours of battle ... [it] must be used in war in cooperation with a field force of efficiency and stamina' which would have to do most of the fighting.[33]

In May 1955 the British finally withdrew from Iraq. The Iraqi authorities said during the withdrawal negotiations that a motorised infantry brigade was to be formed, based at the previous RAF Habbaniya, a location that had been occupied by the British Iraq Levies.[34]

Republic declared

The Hashemite monarchy lasted until 1958, when it was overthrown through a coup d'état by the Iraqi Army, known as the 14 July Revolution. King Faisal II of Iraq along with members of the royal family were murdered. The coup brought Abd al-Karim Qasim to power. He withdrew from the Baghdad Pact and established friendly relations with the Soviet Union.

When Qāsim distanced himself from Abd an-Nāsir, he faced growing opposition from pro-Egypt officers in the Iraqi army. `Arif, who wanted closer cooperation with Egypt, was stripped of his responsibilities and thrown in prison. When the garrison in Mosul rebelled against Qāsim's policies, he allowed the Kurdish leader Barzānī to return from exile in the Soviet Union to help suppress the pro-Nāsir rebels.

The creation of the new Fifth Division, consisting of mechanized infantry, was announced on 6 January 1959, Army Day.[35] Qāsim was also promoted to the rank of general.

In 1961, an Army build up close to Kuwait in conjunction with Iraqi claims over the small neighbouring state, led to a crisis with British military forces (land, sea, and air) deployed to Kuwait for a period. In 1961, Kuwait gained independence from Britain and Iraq claimed sovereignty over Kuwait. As in the 1930s, Qasim based Iraq's claim on the assertion that Kuwait had been a district of the Ottoman province of Basra, unjustly severed by the British from the main body of Iraqi state when it had been created in the 1920s.[36] Britain reacted strongly to Iraq's claim and sent troops to Kuwait to deter Iraq. Qāsim was forced to back down and in October 1963, Iraq recognized the sovereignty of Kuwait.

Qāsim was assassinated in February 1963, when the Ba'ath Party took power under the leadership of General Ahmed Hasan al-Bakr (prime minister) and Colonel Abdul Salam Arif (president). Nine months later `Abd as-Salam Muhammad `Arif led a successful coup against the Ba'ath government. On 13 April 1966, President Abdul Salam Arif died in a helicopter crash and was succeeded by his brother, General Abdul Rahman Arif. Following the Six-Day War of 1967, the Ba'ath Party felt strong enough to retake power (17 July 1968). Ahmad Hasan al-Bakr became president and chairman of the Revolutionary Command Council (RCC).

Six-Day War

During the Six-Day War, the Iraqi 3rd Armoured Division was deployed in eastern Jordan.[37] However, the Israeli attack against the West Bank unfolded so quickly that the Iraqi force could not organise itself and reach the front before Jordan ceased fighting. Repeated Israeli airstrikes also held them up so that by the time they did reach the Jordan River the entire West Bank was in Israeli hands. During the course of the Jordanian Campaign ten Iraqis were killed and 30 Iraqis were wounded, especially as the main battle was in Jerusalem. Fighting also raged in other areas of the West Bank, where Iraqi commandos and Jordanian soldiers defended their positions.[38]

Barzānī and the Kurds who had begun a rebellion in 1961 were still causing problems in 1969. The secretary-general of the Ba`th party, Saddam Hussein, was given responsibility to find a solution. It was clear that it was impossible to defeat the Kurds by military means and in 1970 a political agreement was reached between the rebels and the Iraqi government.

Following the Arab defeat in 1967, Jordan became a hotbed of Palestinian activity. During this time PLO elements attempted to create a Palestinian state within Jordan caused the Jordanians to launch their full military force against the PLO. As they were doing this Syria invaded Jordan and Iraq moved a brigade in Rihab, Jordan. Otherwise the only Iraqi activity was that they fired upon some Jordanian aircraft.

Yom Kippur War

Iraq sent a 60,000 man expeditionary force to the Syrian front during the Yom Kippur War. It consisted of the 3rd and 6th Armoured Divisions, two infantry brigades, twelve artillery battalions, and a special forces brigade. The two armoured divisions were, Pollack says, 'unquestionably the best formations of the Iraqi Army.'[37] Yet during their operations on the Golan Heights, their performance was awful in virtually every category of military effectiveness. Military intelligence, initiative, and small unit independent action was virtually absent.[39]

After the war, Iraq started a major military build-up. Active duty manpower doubled, and so did number of divisions, from six to twelve, of which four were now armoured and two mechanised infantry.[40]

Iran–Iraq war

Later, Saddam Hussein, looking to build fighting power against Iran soon after the outbreak of the Iran–Iraq War doubled the size of the Iraqi Army. In 1981, Pollack writes it numbered 200,000 soldiers in 12 divisions and 3 independent brigades, but by 1985, it reached 500,000 men in 23 divisions and nine brigades. An April 1983 CIA estimate suggests that Iraq had at that time five armoured; seven infantry; and two mechanised infantry divisions with ten more forming ("several are probably already operational").[41] The first new divisions were created in 1981 when the 11th and 12th Border Guard Divisions were converted into infantry formations and the 14th Infantry Division was formed.[42] Yet the rise in number of divisions is misleading, because during the war Iraqi divisions abandoned a standard organisation with permanent ('organic') brigades assigned to each division. Instead division headquarters were assigned a mission or sector and then assigned brigades to carry out the task - up to eight to ten brigades on some occasions.[43]

The war came at a great cost in lives and economic damage - a half a million Iraqi and Iranian soldiers as well as civilians are believed to have died in the war with many more injured and wounded - but brought neither reparations nor change in borders. The conflict is often compared to World War I,[44] in that the tactics used closely mirrored those of the 1914–1918 war, including large scale trench warfare, manned machine-gun posts, bayonet charges, use of barbed wire across trenches and on no-mans land, human wave attacks by Iran, and Iraq's extensive use of chemical weapons (such as mustard gas) against Iranian troops and civilians as well as Iraqi Kurds.

Invasion of Kuwait and the Persian Gulf War

By the eve of the Invasion of Kuwait which led to the 1991 Persian Gulf War, the army was estimated to number 1,000,000 men.[45] Just before the Persian Gulf War began, the force comprised 47 infantry divisions plus 9 armoured and mechanised divisions, grouped in 7 corps.[46] This gave a total of about 56 army divisions, and total land force divisions reached 68 when the 12 Iraqi Republican Guard divisions were included. Eisenstadt notes that four Republican Guards security divisions were formed between the invasion of Kuwait and the outbreak of war. They remained in Iraq during the war.[46] Although the coalition ground forces believed they faced approximately 545,000 Iraqi troops at the beginning of the ground campaign,[47] the quantitative descriptions of the Iraqi army at the time were exaggerated, for a variety of reasons.[48] Many of the Iraqi troops were also young, under-resourced and poorly trained conscripts. Saddam did not trust the army; among counterbalancing security forces was the Iraqi Popular Army.

The wide range of suppliers of Iraqi equipment resulted in a lack of standardization. It additionally suffered from poor training and poor motivation. The majority of Iraqi armoured forces still used old Chinese Type 59s and Type 69s, Soviet-made T-55s & T-62s from the 1950s and 1960s, and some T-72s from the 1970s in 1991. These vehicles were not equipped with up-to-date equipment, such as thermal sights or laser rangefinders, and their effectiveness in modern combat was very limited. The Iraqis failed to find effective countermeasures to the thermal sights and the sabot rounds used by M1 Abrams, Challenger 1 and other tanks of the Allied forces. U.S. M1A1s could effectively engage and destroy Iraqi tanks from well outside the distance (e.g. 8,200 ft to Iraqi ranges of 6,600 ft) that Iraqi tanks could engage.

The Iraqi tank guns were supplied with older generation steel core penetrators which, while perfectly well suited to older Iranian tanks, against the advanced Chobham Armour of the latest US and British tanks of the coalition the results were disastrous. The Iraqi forces also failed to utilize the advantage that could be gained from using urban warfare — fighting within Kuwait City — which could have inflicted significant casualties on the attacking forces. Urban combat reduces the range at which fighting occurs and can negate some of the technological advantage that well equipped forces enjoy. Iraqis also tried to use Soviet military doctrine, but the implementation failed due to the lack of skill of their commanders and the preventive air strikes of the USAF and RAF on communication centers and bunkers.

While the exact number of Iraqi combat casualties has yet to be firmly determined, sources agree that the losses were substantial. Immediate estimates said up to 100,000 Iraqis were killed. More recent estimates indicate that Iraq probably sustained between 20,000 and 35,000 fatalities, though other figures still maintain fatalities could have been as high as 200,000.[49] A report commissioned by the U.S. Air Force, estimated 10,000-12,000 Iraqi combat deaths in the air campaign and as many as 10,000 casualties in the ground war.[50] This analysis is based on Iraqi prisoner of war reports. It is known that between 20,000 and 200,000 Iraqi soldiers were killed. According to the Project on Defense Alternatives study,[51] 3,664 Iraqi civilians and between 20,000 and 26,000 military personnel were killed in the conflict. 75,000 Iraqi soldiers were wounded in the fighting.

The International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) estimated the army's composition immediately after the 1991 war as six 'armoured'/'mechanised' divisions, 23 infantry divisions, eight Republican Guard divisions and four Republican Guard internal security divisions.[52] Jane's Defence Weekly for 18 July 1992 stated that 10,000 troops from five divisions were fighting against Shia Muslims in the southern marshlands.

The IISS gave the Iraqi Army's force structure as of 1 July 1997 as seven Corps headquarters, six armoured or mechanised divisions, 12 infantry divisions, six RGF divisions, four Special Republican Guard Brigades, 10 commando, and two Special Forces Brigades.[53] It was estimated to number 350,000 personnel, including 100,000 recently recalled reservists.[53]

U.S. invasion 2003

In the days leading up to the U.S. 2003 invasion of Iraq and the following Iraq War, the army consisted of 375,000 troops, organized into five corps. In all, there were 11 infantry divisions, 3 mechanized divisions, and 3 armored divisions. The Republican Guard consisted of between 50,000 and 60,000 troops (although some sources indicate a strength of up to 80,000).

In January 2003, before the start of the invasion of Iraq in March 2003, the force was primarily located in eastern Iraq. The five corps were organised as follows:

- 1st Corps, near Kirkuk consisted of the 5th Mechanized Division, 2nd Infantry Division, 8th Infantry Division and the 38th Infantry Division.[54]

- 2nd Corps, near Diyala (CNN)[55] had the 3rd Armored Division (HQ Jalawia), 15th Infantry Division (HQ Amerli), and 34th Infantry Division.[54]

- 3rd Corps, near An Nasiriyah and the Kuwaiti border, had the 6th Armored Division, the 51st Mechanized Division, and the 11th Infantry Division.[56] The 11th Infantry Division defended An Nasiriyah and As Samawah to the southeast on the approaches to An Nasiriyah.[57]

- 4th Corps, near Amarah and the border with Iran, included the 10th Armored Division, 14th Infantry Division and 18th Infantry Division.[58]

- 5th Corps (Iraq), with its headquarters at Mosul, covering border areas with Syria and Turkey, had the 1st Mechanised Division, and the 4th, 7th, and 16th Infantry Divisions.[59]

- Western Desert Force, consisting of an armored infantry division and other units in western Iraq. Malovany's description of deployments generally follows this pattern; A special headquarters was established on the eve of the war called the "Great Day" to command forces defending the Anbar district in west Iraq and the axes leading from it towards Baghdad.[60]

During the 2003 invasion of Iraq the Iraqi Army was defeated in a number of battles, including by Task Force Viking in the north, and the Battle of Nasiriyah and the Battle of Baghdad. The Iraqi Army was disbanded by Coalition Provisional Authority Order Number 2 issued by U.S. Administrator of Iraq Paul Bremer on May 23, 2003, after its decisive defeat.[61] Bremer said that it was not feasible to reconstitute the armed forces. His justifications for the disbandment included postwar looting, which had destroyed all the bases; that the largely Shiite draftees of the army would not respond to a recall plea from their former commanders, who were primarily Sunnis, and that recalling the army "would be a political disaster because to the vast majority of Iraqis it was a symbol of the old Baathist-led Sunni ascendancy".[62]

Formations of the army, 1922–2003

Corps

- 1st Corps – established before Iran-Iraq War.

- 2nd Corps – reorganised as an armoured corps for the 1991 Gulf War, comprising the 17th Armoured Division and the 51st Mechanised Division

- 3rd Corps – established before Iran-Iraq War. In 1978 reported to be headquartered at Nasariyah and to consist of 1st and 5th Mechanised Divisions and 9th Armoured Division. In 2003, Nasiriyah was the headquarters of the Iraqi Army's 3rd Corps, composed of the 11th ID, 51st Mech ID, and 6th Armored Division—all at around 50 percent strength. The 51st operated south covering the oilfields, and the 6th was north near Al Amarah, which left three brigade-sized elements of the 11th ID to guard the An Nasiriyah area.[63]

- 4th Corps – established 22 October 1981 to take over the northern sector of Khuzestan Province, including Basitin, Shush, and Dezful sectors. Maj Gen Hisham Sahab al-Fakhri, previously 10th Armoured Division commander, was appointed as the corps commander. 1st Mechanised, 10th Armoured, and 14th Infantry Division were allocated to the corps, leaving 3rd Corps with 3rd and 9th Armoured, 5th Mechanised, and 11th Infantry Divisions.[64]

Senior generals of the Iraq Army at the Gizlani military base in Mosul, 1960's.

Senior generals of the Iraq Army at the Gizlani military base in Mosul, 1960's. - 5th Corps

- 6th Corps – Malovany 2017 writes that on 25 March 1985, an army meeting chaired by Saddam in Baghdad decided to transform the East Tigris Headquarters into a regular corps, the 6th Corps. It was to be reinforced with four additional divisions; as the 35th Division had been transferred to the 4th Corps, and the 32nd Division was with the East Tigris HQ, the new line-up would consist of the 32nd Division as before; the 12th Armoured Division and 2nd Infantry Division transferred both from the 2nd Corps; the 4th Infantry Division, and the 25th Infantry Division from the 4th Corps.[65] Malovany adds on the same page that during 1986 two more divisions joined the 6th Corps, an infantry division ("apparently the 50th") and the "Marshes" Division.

- 7th Corps

- Jihad Forces (Persian Gulf War of 1991)

Infantry and mechanised divisions

- 1st Division, active from at least 1941. 1st Mechanised Division in Persian Gulf War and Iraq War. Reformed after 2003.

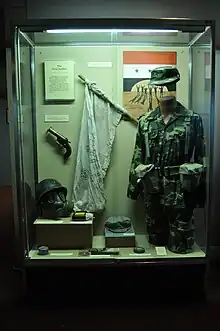

Exhibit "The Iraqi soldier" about the Gulf War in Fort Lewis Military Museum.

Exhibit "The Iraqi soldier" about the Gulf War in Fort Lewis Military Museum. - 2nd Division, active from at least 1941

- 3rd Division, active from at least 1941. Served in Iran–Iraq War

- 4th Division, active from at least 1941. As 4th Mountain Infantry Division, served in Iran–Iraq War.

- 5th Division, activated 1959. Served in Iran–Iraq War. As 5th Mechanised Division, fought in Battle of Khafji.

- 7th Division, served in Iran–Iraq War

- 8th Division. As 8th Mountain Infantry Division, served in Iran–Iraq War.

- 11th Division, served in Iran–Iraq War, Persian Gulf War

- 14th Division

- 15th Division, served in Iran–Iraq War (Operation Beit-ol-Moqaddas)

- 16th, 18th, 19th, 20th, 21st, 22nd, 23rd, 24th, 25th Divisions,

- 26th, 27th,[66] 28th, 28th, 30th, 31st, 33rd, 34th, 36th, 37th, 38th Divisions

- 39th, 42nd, 44th, 45th, 46th, 47th, 48th, 49th, 50th Divisions

- 51st Mechanised Division (Iraq) (serious morale problems before invasion; expected anti-Saddam regime outbreaks in Basra and Az Zubayr, had contingency plans for 'terminating enemy agents and mobs.'[67] Surrendered during Iraqi Freedom 22 March 2003[68])

- 53rd, 54th, 56th Divisions

- Eisenstadt reported 'about eight infantry divisions remain unaccounted for' as of March 1993.[46]

Armoured divisions up to 2003

- 3rd Armoured Division, active by 1967, served in Yom Kippur War, Iran–Iraq War

- 6th Armoured Division, served in Yom Kippur War, Iran–Iraq War

- 9th Armoured Division (Iraq), served in Iran–Iraq War, disbanded after First Battle of Basrah/Operation Ramadan, July 1982.[69] Reformed after 2003.

- 10th Armoured Division, served in Iran–Iraq War, in Persian Gulf War with Jihad Forces (corps)

- 12th Armoured Division, served in Iran–Iraq War, Persian Gulf War with Jihad Forces (corps)

- 17th Armoured Division[70]

- 52nd Armoured Division, sat passive then elements destroyed by British 1st Armoured Division during Operation Granby/Battle of Norfolk in February 1991.[71]

Brigades

The 65th Special Forces Brigade, 66th Special Forces Brigade, 68th Special Forces Brigade, and 440th Marine Brigade were active during the Persian Gulf War.[72]

Rebuilding an Army from 2003

Based on Bush administration expectations that coalition forces would be welcomed as liberators after the overthrow of the Hussein regime,[73] prewar planners had only been expecting little if any resistance from the Iraqi people. Thus the new army was initially focused on external defence operations. The new Army was originally intended to comprise 27 battalions in three divisions numbering 40,000 soldiers in three years time.[74] Vinnell Corporation was engaged to train the first nine battalions.[75]

The Coalition Military Assistance Training Team (CMATT), headed by Major General Paul Eaton, was organized by the Department of Defense with the responsibility of training and development of the new army. On August 2, 2003, the first battalion of new Iraqi Army recruits started a nine-week training course at a training base in Qaraqosh. They graduated on October 4, 2003.[76] In the interim, the new army had been formally established by Coalition Provisional Authority Order 22 of August 18, 2003.[77]

In April 2004, several Iraqi battalions refused to fight as part of the force engaged in the First Battle of Fallujah.[78] The Fifth Battalion was among the new Iraqi units that fought in Fallujah.[79] In June 2004, the CMATT was dissolved, and passed on its responsibilities to the Multi-National Security Transition Command – Iraq (MNSTC-I) (initially headed by Lt. Gen. David Petraeus) with the new focus on providing security for the Iraqi people from the emerging threat posed by the Iraqi insurgency.[80]

While the regular army was being formed, U.S. commanders around the country needed additional troops more quickly, and thus the Iraqi Civil Defense Corps (which became the Iraqi National Guard by July 2004)[81] was formed. Coalition commanders formed these militia-type units separately in each area; only later were they gradually brought together as one force. There were several instances where they have refused to take military action against fellow Iraqis, such as in Fallujah, deserted, or allegedly aided the resistance. It is alleged that most guardsmen were drawn from the Shia majority in Southern Iraq or the Kurdish majority in northern Iraq, rather than from the Sunni area which they were ordered to attack. In September 2004, a senior member of the National Guard, General Talib al-Lahibi was arrested on suspicion of having links with insurgent groups.[82] In December 2004, it was announced that the Iraqi National Guard would be dissolved.[83] At this time its strength was officially over 40,000 men. Its units became part of the army. The absorption of the ING by the regular army appears to have taken place on January 6, 2005, Iraqi Army Day.[84]

On August 14, 2004, the NATO Training Mission - Iraq was established to assist the Iraqi military, including the army. On September 20 the provisional Fallujah Brigade dissolved after being sent in to secure the city. The Fallujah Brigade experiment of using former insurgents to secure a city was not repeated.

Army training was transferred from Vinnell Corporation to the United States Department of Defense supported by U.S. allies. It was impeded by domestic instability, infiltration by insurgents, and high desertion rates. By June 2005, the number of battalions in the new army had grown to around 115. Out of this number, it was deemed that 80 were able to carry out operations in the field with Coalition support limited to logistics and strategic planning, whilst another 20-30 battalions still needed major Coalition support to carry out their operations. As of October 5, 2005 the Iraqi Army had 90 battalions trained well enough to be "deployed independently", without United States help.[85]

On May 3, 2006, a significant command-and-control development took place. The Iraqi Army command and control center opened in a ceremony at the Iraqi Ground Forces Command (IFGC) headquarters at Camp Victory.[86] The IGFC was established to exercise command and control of assigned Iraqi Army forces and, upon assuming Operational Control, to plan and direct operations to defeat the Iraqi insurgency. At the time, the IFGC was commanded by Lt. Gen. Abdul-Qadar. In 2006 the ten planned divisions began to be certified and assume battlespace responsibility: the 6th and 8th before June 26, 2006, the 9th on June 26, 2006, the 5th on July 3, 2006, the 4th on August 8, 2006, and the 2nd on December 21, 2006. After divisions were certified, they began to be transferred from U.S. operational control to Iraqi control of the IGFC. The 8th Division was transferred on September 7, 2006,[87][88] and the 3rd Division on December 1, 2006. Another unspecified division also was transferred to IGFC control.[89] Also transferred to the Iraqi chain of command were smaller logistics units: on November 1, 2006, the 5th Motor Transport Regiment (MTR) was the fifth of nine MTRs to be transferred to the Iraqi Army divisions. 2007 plans included, MNF-I said, great efforts to make the Iraqi Army able to sustain itself logistically.[90]

As of June 26, 2006, three Iraqi divisions, 18 brigades and 69 battalions were responsible for their own areas of operations (including two police commando battalions).[91]

2008

.jpg.webp)

On March 25, 2008, the Iraqi Army launched its first solely planned and executed high-profile division-level operation, Operation Charge of the Knights in Basra. They received Multi-National Force – Iraq support only in air support, logistics and via embedded advisors. Also, a British infantry brigade, part of Multi-National Division South-East, and stationed in Basra, were ready in a tactical overwatch role. Their participation was limited to the provision of embedded training teams.

In April–June 2008, two brigades of the Iraqi Army 11th Division, supported by US forces, moved into the southern third of Sadr City. They were tasked to stop rocket and mortar attacks on US bases and the Green Zone. Following the Siege of Sadr City—a month of fighting—the Mahdi Army agreed to let Iraqi forces into the remaining portion of the city. On May 20, troops from the Iraqi Army 3rd Brigade of the 1st (Iraqi Reaction Force) Division and a brigade from the 9th Division moved into the northern districts of Sadr City and began clearing operations.

In May, Iraqi army forces launched Operation Lion's Roar (later renamed to Operation Mother of Two Springs) in Mosul and surrounding areas of Nineveh Governorate. Iraq became one of the top purchasers of U.S. military equipment with the Iraqi army trading its AK-47 assault rifles for the more accurate U.S. M-16 and M-4 rifles, among other equipment.[92]

In June 2008 the army moved troops to the southern Maysan Governorate. Following a four-day amnesty for insurgents to turn over weapons, the Iraqi Army moved into the provincial capital Amarah.

In late 2008, United States personnel were worried by Prime Minister Maliki's attempt to exert control over the Iraqi Army and police by proliferating regional operations commands. "Using the Baghdad Operations Command as his precedent, Maliki created other regional commands in Basrah, Diyala, the mid-Euphrates region, and Ninawa, and others would follow. Initially coalition leaders welcomed the idea of regional commands that could create unity of Iraqi effort, but their enthusiasm faded as Maliki began to use the new headquarters to bypass the formal chain of command,"[93] which came to resemble the operating mode of the Saddam Hussein regime.

Divisions are forming engineer, logistics, mortar, and other units by identifying over-strength units, such as the Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR) battalions and other headquarters elements, and then transferring them as needed.

Problems include infiltration and an insufficient US advisory effort. Former members of the Special Republican Guard, members of the intelligence services, senior level officials of the Ba'ath Party, people affiliated with terrorist organizations, and anyone with human rights violations or crimes against humanity were prohibited from entering the new army.[77] However the army was infiltrated by a multitude of groups ranging from local militias to foreign insurgents. This has led to highly publicized deaths and compromised operations (perhaps the most prominent being the attack on a US military base near Mosul in December 2004. More than 20 people, including 13 American servicemen, were killed when a suicide bomber wearing an Iraqi military uniform detonated his vest inside a dining tent).[94]

2011

In 2011 Lieutenant General Michael Barbero, Commanding General, MNSTC-I, made an assessment of the Iraqi Armed Forces' shortcomings. Michael Gordon summarized Barbero's findings as:

"..for all the U.S. efforts, Iraq’s special operations forces continued being flown to their targets on American helicopters and relied heavily on U.S. intelligence to plan their missions. Iraqi tank crews, artillery batteries, and infantry battalions had been trained separately and were not practiced in combined arms warfare.

Logistics remained a challenge, and the Iraqi Army had an enormous and costly maintenance backlog. The Iraqis had no counter-battery radar system to pinpoint the location of rocket attacks on the Green Zone—the fortified sanctuary that served as the seat of the Iraqi government—or, as yet, an air force that could protect the nation’s skies. In short, Barbero concluded, Iraq had a “checkpoint army” that was very much a work in progress."[95]

The response from Iraqi officials was that U.S. troops would have to stay longer.

2012

Each of the joint and multi-agency operational commands also include the Department of Border Enforcement, Federal Police, Emergency Police, Oil Police, FPS, etc. in their command as well as Iraqi Army.

As of the Fall of 2012, the Iraqi Army was organized as follows:

- National Operations Center – Baghdad

- Baghdad Operational Command – Baghdad[96] – Lt. Gen. Abud Qanbar

- Karkh Area Command (KAC) – Western Baghdad. Responsible for the Kadhimiyah, Karkh, Mansour, Bayaa, and Doura Security Districts.

- Rusafa Area Command (RAC) – Eastern Baghdad. Responsible for the Adhamiyah, Rusafa, Sadr City, New Baghdad, and Karadah Security Districts.

- 6th Motorised Division – Western Baghdad.

- 9th Armored Division – Taji – Division certified and assumes responsibility of the battle space of the northern Baghdad Governorate on June 26, 2006.[97]

- 11th Infantry Division – East Baghdad (probably planned to become a mechanized division).

- 17th Commando Division – HQ Mahmadiyah The 17th Division commander has been reported as Staff Maj. Gen. Ali Jassam Mohammad.

- Ninewa Operational Command – Mosul.[98] The command dissolved in 2014, but them was reformed in April 2015.[99] It held responsibility for all anti-ISIS operations in Ninewa Province.[100]

- 2nd Division – dissolved and collapsed in Fall of Mosul, mid 2014[101]

- 3rd Motorised Division – Al-Kasik dissolved after defeat by ISIS in 2014

- 15th Division Formed in 2015

- 16th Division - 75th, 76, 91st Brigades[100]

- Diyala Operational Command – Sulamaniyah, Diyala, Kirkuk, Salahadin

- 4th Motorised Division – Tikrit – Division certified on August 8, 2006.[102]

- 5th Infantry Division (Iron) – Diyala Governorate – Division certified on July 3, 2006.[103]

- 12th Motorized Division – Tikrit – split off from 4 Division in mid-2008.

- Basra Operations Command – Basrah

- 8th Commando Division – HQ Diwaniyah

- 10th Division – Nasiriyah

- 14th Division – HQ Basrah[104] – division commander Maj. Gen. Abdul Aziz Noor Swady al Dalmy[105]

- Anbar Operational Command – Ramadi

- 1st Infantry Division – suffered heavy casualties from ISIS in Fallujah in 2014[106]

- 7th Infantry Division – Ramadi, West Al Anbar Province – transferred to Iraqi Ground Forces Command on November 1, 2007.[107]

- Baghdad Operational Command – Baghdad[96] – Lt. Gen. Abud Qanbar

U.S. Military Transition Teams

Up until 2010–2011, all Iraqi Army battalions were supposed to have had embedded U.S. Military transition teams. The MiTTs provided intelligence, communications, fire support, logistics and infantry tactics advice. Larger scale operations were often done jointly with U.S. forces. The training aimed to make the battalion self-sustainable tactically, operationally and logistically so that the battalion would have been prepared to take over responsibility for a particular area.

As of March 2007, the United States Department of Defense reported that 6000 advisors in 480+ teams were embedded with Iraqi units.[108] However, in April, the Congressional Research Service reported that only around 4000 U.S. forces were embedded with Iraqi units at a rate of 10 per battalion.[109] Former U.S. Army analyst Andrew Krepinevich argued that the roughly twelve advisors per Iraqi battalion (approximately 500 troops) was less than half the sufficient amount needed to efficiently implement the combat advisory effort.[110] Krepinevich argues that officers try to avoid taking on advisory tasks due to the US Army's practice of prioritising the promotion of officers that have served with a U.S. unit over ones that have served with foreign forces.[111]

Advisors remained after all U.S. combat brigades left Iraq in August 2010.[112] These troops were required to leave Iraq by 31 December 2011 under an agreement between the U.S. and Iraqi governments.[113]

2014–2016

In the summer of 2014, large elements of the Iraqi army were routed by a much smaller and less well-equipped force from the Islamic State. "[N]ineteen Iraqi Army brigades and six Federal Police brigades disintegrated, a quarter of Iraq's security forces. These losses comprised all of the Ninawa-based 2nd and 3rd Iraqi Army divisions; most of the Salah al-Din-based 4th Iraqi Army division; all of the Kirkuk-based 12th Iraqi Army division; plus at least five southern Iraqi Army brigades that had previously been redeployed to the Syrian border."[114] Islamic State managed to conquer large swaths of Al Anbar Governorate and Iraq's second largest city, Mosul.

Budget problems continued to hinder the manning of combat support and combat service support units. The lack of soldiers entering boot camp is forcing Iraqi leaders at all levels to face the dual challenge of manning and training enabler units out of existing manpower. In the 2015 Pentagon budget, a further $1.3 billion has been requested to provide weapons for the Iraqi Army.[7] However, the New York Times reported that "some of the weaponry recently supplied by the army has already ended up on the black market and in the hands of Islamic State fighters". The same November 2014 article contended that corruption is endemic in the Iraqi Army. It quoted Col. Shaaban al-Obeidi of the internal security forces, who told the paper: "Corruption is everywhere." The article claimed that one Iraqi general is known as "chicken guy" because of his reputation for selling the soldiers' poultry provisions.[7]

_March_2020.jpg.webp)

In late June 2014, after the large-scale Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant offensive in the north of Iraq, it was reported that ISIL ""took the weapons stores of the 2nd and 3rd [Iraqi army] divisions in Mosul, the 4th division in Salah al Din, the 12th division in the areas near Kirkuk, and another division in Diyala (the 5th Division)," said Jabbar Yawar, secretary-general of the Kurkish Ministry of Peshmerga Affairs.[115]

Reuters reported that the 5th Division (Iraq), located in Diyala Governorate, was by October 2014 reporting to informal "militias' chain of command," not to the Iraqi Army, according to several U.S. and coalition military officials.[116]

A much later report from Small Wars Journal said that in "..2013 and 2014 the 7th Division of the Iraqi Army, 99% Sunni, fought IS virtually alone, until it was almost completely destroyed."[117]

The October 2014 Reuters report quoted Lieutenant General Mick Bednarek, Chief of the Office of Security Cooperation, in Iraq from 2013 until July 2014, as estimating that "the army has only five functioning divisions ... whose fighting readiness ranges between 60 and 65 percent."

The new government under Haider al-Abadi dismissed the Iraqi Ground Forces Command commander General Ali Ghaidan Majid (circa September 2014) and the Iraqi Army chief of operations, General Aboud Kanbar. Lieutenant General Riyadh Tawfiq, the former head of the Ninewa Operational Command, was appointed as the new head of the IGFC and the Mosul Liberation Command.[118]

Michael Knights wrote in 2016 that the rebuilding from the mid-2014 disaster had been steady but "very slow". "By January 2015 a fair number of brigades had been salvaged and a couple of new brigades were built but the overall frontline combat strength of the ISF was halved due to attrition in the manning of each brigade. [U]nits were weaker and many were too demoralized or lightly equipped to do more than hold in place. A year later, by January 2016, significant progress has been made in terms of available forces albeit largely by shuffling around personnel and raising around a dozen new and very small 1,000-strong brigades."[119] The new 15th and 16th Divisions have been identified, which appear to comprise some of the new brigades that Knights mentions, including the 71st, 72nd, 73rd, 75th, and 76th.

Structure

_training_April_2011.jpg.webp)

The Iraqi Army began the Anglo-Iraqi War with a force of four divisions. A fifth was formed in 1959. By the outbreak of the Iran–Iraq War, the force had grown to nine divisions. By 1990, with wartime expansion, the force had grown greatly to at least 56 divisions, making the Iraqi army the fourth largest army in the world and one of the strongest in the Middle East. After the defeat in the Persian Gulf War in 1991, force size dropped to around 23 divisions, as well as Republican Guard formations. The new army formed after 2003 was initially planned to be three divisions strong, but was then raised to ten divisions, and more later.

The U.S. House Armed Services Committee commented in 2007 that "It is important to note that in the initial fielding plan, five army divisions would be tied to the regions from where they were recruited and the other five would be deployable throughout Iraq. This was partially due to the legacy of some army divisions being formed from the National Guard units and has caused some complications in terms of making these forces available for operations in all areas of Iraq, and the military becoming a truly national, non-sectarian force."[120]

According to the United States Department of Defense Measuring Safety and Security in Iraq report of August 2006, plans at that time called for the Iraqi Army to be built up to an approximately 137,500-person force. This was based around an Army with 9 infantry divisions and one mechanised division consisting of 36 brigades and 112 battalions. Nine Motorized Transportation Regiments, 5 logistics battalions, 2 support battalions, 5 Regional Support Units, and 91 Garrison Support Units were intended to provide logistics and support for each division, with Taji National Depot providing depot-level maintenance and resupply. Each battalion, brigade, and division headquarters was to be supported by a Headquarters and Service Company (HSC) providing logistical and maintenance support. The army was also planned to include 17 Strategic Infrastructure Battalions and an Iraqi Special Operations Forces brigade of two battalions.[121]

The Iraqi Army consists of nine regional joint commands. The Joint Operational Commands fall under the command of the National Operations Center. The Iraqi Ground Forces Command does not directly command the army's divisions.

As of July 2009, the Iraqi Army had 14 divisions (1st-12th, 14th, and 17th, the designation 13 not being used), containing 56 brigades or 185 combat battalions. The designations "15th" and "16th" had been reserved for forces to be formed from the Kurds (which did not eventuate). Each division had four line brigades, an engineering regiment, and a support regiment. However both the 6th Division and the 17th Division only had three manoeuvre brigades each. By April 2010, the combat battalion total had risen to 197 combat battalions.

Three of the 56 brigades are not Iraqi Ground Forces Command combatant brigades and were not assigned to a division. They are the Baghdad Brigade formed in the fall of 2008, the 1st Presidential Brigade formed in January 2008, and the 2nd Presidential Brigade formed in the spring of 2009.

After the Fall of Mosul to ISIS, a number of new Iraqi formations and units were created. Among them was (finally) a division numbered "16th" which was "new" when the 82nd Airborne Division's 3rd Brigade arrived in 2015, and operational by November 2015 after fighting in Ramadi.[122] In November 2014 the first units of the new 15th and 16th Divisions held graduation ceremonies.[123]

The Institute for the Study of War said in their 29 December 2014 situation report that "..The 19th Division is a new military formation intended to include members from the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and 12th IA divisions that melted away during the rapid advance of ISIS in June 2014. This formation will almost certainly include volunteer fighters, most likely displaced persons from Mosul, who reside in refugee camps. The.. sectarian composition of the unit will be important to watch. The formation of the division was initially proposed by Defense Minister Khaled al-Obaidi on November 4, 2014 during a visit to Iraqi Kurdistan. During that visit he requested assistance from the Kurdistan Regional Government [with] basing the new division in Iraqi Kurdistan and giving the force responsibility for clearing Mosul."[124] The 19th Division was not listed in either the Institute's 2017 listing of units, or the IISS Military Balance 2022.

In late 2020, the International Institute for Strategic Studies estimated that the Army was about 180,000 strong, with three SF brigades, a ranger brigade HQ which supervised one ranger battalion; the 9th Armoured Division (2 armoured brigades, 2 mech bdes); the 5th, 8th & 10th Divisions with four mechanised infantry brigades each; the 7th Mechanised Division with 2 mech inf bde and 1 inf bde; the 6th Motorised Division with three motorised infantry brigades and an infantry brigade; the 14th Motorised Division with five motorised and infantry brigades; the 1st Infantry Division with two infantry brigades; the 11th Infantry Division with three light inf brigades; the 15th Infantry Division with five infantry brigades; the 16th Infantry Division with two infantry brigades; the 17th Commando Division with four infantry brigades; the independent 17th Infantry Brigade; and the Prime Minister's Security Force division of three infantry brigades.[125]

The Counter-Terrorism Service is a Ministry of Defence (Iraq) funded component that reports directly to the Prime Minister of Iraq.[126]

Rank insignia

Training

There are three levels of troop capability in the new army: one, two, and three. Level three refers to troops that have just completed basic training, level two refers to troops that are able to work with soldiers, and level one refers to troops that can work by themselves.

Members of NATO Training Mission – Iraq (NTM-I) opened a Joint Staff College in ar Rustamiyah in Baghdad on September 27, 2005, with 300 trainers. Training at bases in Norway, Italy, Jordan, Germany, and Egypt has also taken place and 16 NATO countries have allocated forces to the training effort.[127]

The Multi-National Force Iraq has also conducted a variety of training programs for both enlisted soldiers and officers including training as medics, engineers, quartermasters, and military police. Beyond the various courses and programs being held in-country, both American staff colleges and military academies have begun taking Iraqi applicants, with Iraqi cadets being enrolled at both the United States Military Academy and the US Air Force Academy.[128]

Recruits and enlisted soldiers

Iraqi Army recruits undergo a standard eight-week[109] basic training course that includes basic soldiering skills, weapons marksmanship and individual tactics. Former soldiers are eligible for an abbreviated three-week "Direct Recruit Replacement Training" course designed to replace regular basic training to be followed by more training once they have been assigned to a unit.

Soldiers later go on to enroll in more specific advanced courses targeted for their respective fields. This could involve going to the Military Intelligence School, the Signal School, the Bomb Disposal School, the Combat Arms Branch School, the Engineer School, and the Military Police School.

Officers

The Iraqi Armed Service and Supply Institute located in Taji plays a significant role in training aspiring Iraqi non-commissioned officers and commissioned officers. The training is based on the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst model, chosen in part due to its shorter graduation time compared to West Point. Much of the Iraqi officer training programme is copied directly from the Sandhurst course.

Equipment

Virtually all of the equipment used by the former Iraqi Army was either destroyed by the U.S. and British forces during the 2003 invasion, or was looted during the chaotic aftermath shortly after the fall of the Hussein regime. Among these were more than 20,000 sets of body armor.[129] Four T-55 tanks however have been recovered from an old army base in al-Muqdadiyah and are now in service with the 1st Division.

In February 2004 the U.S. government announced that Nour USA was awarded a $327,485,798 contract to procure equipment for both the Iraqi Army and the Iraqi National Guard; however, this contract was canceled in March 2004 when an internal Army investigation (initiated due to complaints from losing bidders) revealed that Army procurement officers in Iraq were violating procedures with sloppy contract language and incomplete paperwork. On May of that same year the U.S. Army Tank-automotive and Armaments Command (TACOM) stated that they would award a contract worth $259,321,656 to ANHAM Joint Venture in exchange for procuring the necessary equipment (and providing its required training) for a minimum of 15 and a maximum of 35 battalions. The minimum bid would begin to be delivered immediately and further orders could be placed until the maximum of 35 battalion sets or September 2006 after the first order was fully delivered.

In May 2005, Hungary agreed to donate 77 T-72s to the Iraqi Army, with the refurbishment contract going to Defense Solutions to bring the tanks up to operational status for an estimated 4.5 million dollars US.[130] After a delay in the payment of funds from the Iraqi government,[131] the 9th Mechanised Division received the tanks at its headquarters in Taji over a three-day period starting on November 8, 2005.[130]

On July 29, 2005, the United Arab Emirates gained approval to purchase 180 M113A1 APCs in good condition from Switzerland, with the intent to transfer them to Iraq as a gift. Domestic political opposition in Switzerland successfully froze the sale, fearing that the export would violate the country's longstanding tradition of neutrality as well as perhaps make Switzerland a target for terrorism.[132]

173 M113s, 44 APC Talhas, and 100 FV103 Spartans were donated by Jordan, Pakistan and UAE. 600 AMZ Dzik-3 (Ain Jaria) APCs were ordered in Poland (option for 1,200) for delivery by Jan 2007. 573 Otokar Akrep APCs for delivery by Jan 2007. 756 Iraqi Light Armored Vehicles (option for 1,050) for delivery by November 2008.[133][134] Greece donated 100 BMP-1 to the Iraqi Army.

713 M1114 and 400 M1151 HMMWVs purchased for IA with delivery complete by end July 2006.

Serbia has signed a US$230m deal with Iraq to sell weapons and military equipment, the defence ministry said in March 2008. It did not specify the weapons but Serbian military experts believe they include Serbian-made CZ-99 hand guns, Zastava M21 5.56 mm assault rifles, Zastava M84 machine guns, anti-tank weapons (M79 "Osa", Bumbar, and M90 "Strsljen"), ammunition and explosives and about 20 Lasta 95 basic trainer aircraft. Iraq's defence Minister Abdul-Qadir al-Obaidi visited Belgrade in September and November to discuss boosting military ties with Serbia.[135][136]

In August 2008, the United States proposed military sales to Iraq, which will include the latest upgraded M1A1 Abrams battle tanks, attack helicopters, Stryker armored vehicles, modern radios, all to be valued at an estimated $2.16 billion.[137]

In December 2008, the United States approved a $6 billion arms deal with Iraq that included 140 M1A1 Abrams tanks and 400 Stryker combat vehicles for elite Iraqi army units.[138]

In December 2009, Ukraine has signed a deal to deliver $550 million worth of arms to Iraq, the agreement with the Iraqi ministry of defense calls for Ukraine to produce and deliver 420 BTR-4 armored personnel carriers, six AN-32B military transport planes and other military hardware to Iraq.[139]

In February 2009, the United States Department of Defense announced it had struck deals with Iraq that would see Baghdad spend $5 billion on U.S.-made weapons, equipment and training.[140]

In 2016, Iraq finalized an order with Uralvagonzavod for 73 T-90S and SK tanks. The T-90SK is a command variant equipped additional radios and navigation equipment. As of 2018, 36 had been delivered and have been assigned to 35th Brigade of the 9th Armored Division.

Uniforms and personal weapons

The average Iraqi soldier is equipped with an assortment of uniforms ranging from the Desert Camouflage Uniform, the 6 color "Chocolate Chip" DBDU, the woodland-pattern BDU, the U.S. Marine Corps MARPAT, or Jordanian KA7. Nearly all have a PASGT ballistic helmet, Generation I OTV ballistic vest, and radio. Their light weapons consist of stocks of Cold War-era arms, namely the Tabuk series of Zastava M-70 copies and derivatives like the Tabuk Sniper Rifle, the Soviet AKM and the Chinese Type 56 assault rifles, the Zastava M72 and PKM machine guns, and Al-Kadesih sniper rifle though they have received assistance from the U.S. in the form of American-made weapons, including M16A2 and M16A4 rifles and M4 carbines.

However weapons registration is poor. A 2006 report by the Special Inspector General for Iraq Reconstruction (SIGIR) notes that out of the 370,000 weapons turned over to the U.S. since the fall of Saddam's regime, only 12,000 serial numbers have been recorded.[141] The lack of proper accounting for these weapons makes the acquisition of small arms by anti-governmental forces such as insurgents or sectarian militias much easier.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Central Intelligence Agency (2 May 2023). "Iraq". World Fact Book.

- ↑ IISS 2022, p. 328.

- ↑ Al-Marashi & Salama 2008, p. 206 Al-Marashi and Salama note that the eighty-third anniversary of Iraqi Army Day was celebrated in 2004.

- ↑ "Measuring Security and Stability in Iraq" (PDF). U.S. Department of Defense. August 2006. p. 52. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2007-09-11. Retrieved 2007-09-07.

- ↑ "The Gulf Military Balance in 2010" (PDF). Center for Strategic and International Studies. 22 April 2010. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 August 2010. Retrieved 3 July 2013.

- ↑ "Iraq Withdrawal: U.S. Abandoning Plans To Keep Troops In Country". The Huffington Post. 15 October 2011. Archived from the original on 30 December 2011. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Graft Hobbles Iraq's Military In Fighting Isis". The New York Times. 23 November 2014. Archived from the original on 13 October 2017. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Pollack 2002, p. 148.

- ↑ Al-Marashi & Salama 2008, p. 206.

- 1 2 3 Lyman 2005, p. 25.

- ↑ Al-Marashi & Salama 2008, pp. 23–24.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Pollack 2002, p. 149.

- ↑ Simon 1986, pp. 116–119.

- ↑ Simon 1986, p. 116.

- 1 2 3 4 Ghareeb & Dougherty 2004.

- ↑ Finer 1962, pp. 157–158.

- 1 2 Lyman 2005, p. 21.

- ↑ Playfair et al. 2004, p. 182.

- 1 2 Lyman 2005, p. 26.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Pollack 2002, p. 150.

- ↑ O'Ballance, Edgar (1956). The Arab-Israeli War, 1948. London: Faber & Faber. pp. 84, 115.

- ↑ Dupuy 1978, p. 18.

- 1 2 Pollack 2002, p. 448.

- ↑ Pollack 2002, pp. 150–151.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Pollack 2002, p. 151.

- ↑ Dupuy 1978, p. 51.

- ↑ Lorch, Netanel (1961). The Edge of the Sword: Israel's War of Independence 1947-1949. London: G. P. Putnam's Sons. p. 169.

- 1 2 3 Pollack 2002, p. 153.

- ↑ Tal, David (2004). War in Palestine, 1948: Strategy and Diplomacy. London: Routledge. p. 232. ISBN 978-0-203-49954-2. OCLC 647395884.

- ↑ Malovany 2017, pp. 41–43.

- ↑ Malovany 2017, p. 43.

- ↑ Levey 2004, p. 63.

- ↑ Levey 2004, p. 64.

- ↑ Solomon (Sawa) Solomon, "The Assyrian Levies, The Final Chapter" Archived 2011-07-22 at the Wayback Machine, Nineveh Magazine 4Q,93, V16, No4.

- ↑ The Times, 'New Division for Iraq Army,' 7 January 1959

- ↑ Tripp, Charles. A History of Iraq. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2002, p.165

- 1 2 Pollack 2002, p. 167.

- ↑ Follow me- The story of the Six Day War 2. Six Day War- Tom Segev

- ↑ Pollack 2002, pp. 173–175, citing among others Tzvi Ofer, 'The Iraqi Army in the Yom Kippur War,' transl. 'Hatzav,' Tel Aviv: Ma'arachot, 1986, p.128-65. Pollack notes that the various accounts of Iraqi operations on the Golan Heights are highly contradictory. He relies on Ofer, 1986, which is an Israeli General Staff critique of the official Iraqi General Staff analysis of the battle.

- ↑ Pollack 2002, p. 182.

- ↑ Prospects for Iraq, 1 April 1983, accessed September 2020.

- ↑ Pollack 2002, p. 207.

- ↑ Pollack 2002, p. 208.

- ↑ Abrahamian, Ervand, A History of Modern Iran, Cambridge, 2008, p.171

- ↑ Brassey's, IISS Military Balance 1989-90, p.101

- 1 2 3 Eisenstadt 1993, p. 124.

- ↑ Watts, Barry D. (1995). Gordon, Michael R. (ed.). ""Friction in the Gulf War"". Naval War College Review. 48 (4): 94, 106n. ISSN 0028-1484. JSTOR 44637661.

- ↑ Norman Friedman, "Desert Victory," United States Naval Institute Press (distributed by Airlife Publishing Ltd. in UK), 1992/93, ISBN 1-55750-255-2, pages 117-119, 443, 446.

- ↑ Fisk 2005, p. 853.

- ↑ Keaney, Thomas; Eliot A. Cohen (1993). Gulf War Air Power Survey. Department of the Air Force. ISBN 0-16-041950-6.

- ↑ "Wages of War - Appendix 2: Iraqi Combatant and Noncombatant Fatalities in the 1991 Gulf War". Archived from the original on 2009-04-16. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

- ↑ IISS Military Balance 1992-3

- 1 2 IISS 1997.

- 1 2 Fontenot, Degen & Tohn 2004, p. 153.

- ↑ Deployed 'east of Baghdad,' according to Cordesman 2003

- ↑ Malovany 2017, pp. 662–663; Cordesman 2003, p. 46.

- ↑ Fontenot, Degen & Tohn 2004, p. 101, 138.

- ↑ Malovany 2017, pp. 662–663; Cordesman 2003, p. 46; Fontenot, Degen & Tohn 2004, pp. 101, 138.

- ↑ Cordesman 2003, pp. 45–46.

- ↑ Malovany 2017, pp. 662–663.

- ↑ Iraqi Security and Military Force Developments: A Chronology, 2, 4, 6, 7 Archived 2008-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Bremer III, L. Paul (2007-09-06). "How I Didn't Dismantle Iraq's Army". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2009-04-23. Retrieved 2010-05-04.

- ↑ Rohr, Karl. "Fighting Through the Fog of War". Marine Corps Gazette. Archived from the original on December 1, 2008. Retrieved 29 December 2008.

- ↑ Malovany 2017, p. 168.

- ↑ Malovany 2017, p. 277.

- ↑ See Gulf War Air Power Survey, Vol. I, pg 68/97.

- ↑ Craig Smith, "In Documents, Glimpses of Failed Plan for Defence," New York Times, 10 April 2003, cited in Ahmed S. Hashim, Insurgency and Counter-insurgency in Iraq, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, New York, 2006, 9.

- ↑ "CNN.com - Iraqi army division gives up fight - Mar. 22, 2003". edition.cnn.com. Archived from the original on 2016-07-10. Retrieved 2018-05-27.

- ↑ Pollack 2002, p. 205.

- ↑ Malovany 2017, pp. 244, 245, 267, 288.

- ↑ Kenneth Pollack, Armies of Sand, 2019, 162.

- ↑ Eisenstadt 1993.

- ↑ Spearin 2008, p. 229.

- ↑ Wright & Reese 2008, pp. 433–434.

- ↑ Charles Tiefer, "The Iraq Debacle: The Rise and Fall of Procurement-Aided Unilateralism as a Paradigm of Foreign War," University of Pennsylvania Journal of Int'l Law 29 (2007).

- ↑ Wright & Reese 2008, pp. 433–436.

- 1 2 Wright & Reese 2008, p. 435.