In mathematics and theoretical physics, an invariant differential operator is a kind of mathematical map from some objects to an object of similar type. These objects are typically functions on , functions on a manifold, vector valued functions, vector fields, or, more generally, sections of a vector bundle.

In an invariant differential operator , the term differential operator indicates that the value of the map depends only on and the derivatives of in . The word invariant indicates that the operator contains some symmetry. This means that there is a group with a group action on the functions (or other objects in question) and this action is preserved by the operator:

Usually, the action of the group has the meaning of a change of coordinates (change of observer) and the invariance means that the operator has the same expression in all admissible coordinates.

Invariance on homogeneous spaces

Let M = G/H be a homogeneous space for a Lie group G and a Lie subgroup H. Every representation gives rise to a vector bundle

Sections can be identified with

In this form the group G acts on sections via

Now let V and W be two vector bundles over M. Then a differential operator

that maps sections of V to sections of W is called invariant if

for all sections in and elements g in G. All linear invariant differential operators on homogeneous parabolic geometries, i.e. when G is semi-simple and H is a parabolic subgroup, are given dually by homomorphisms of generalized Verma modules.

Invariance in terms of abstract indices

Given two connections and and a one form , we have

for some tensor .[1] Given an equivalence class of connections , we say that an operator is invariant if the form of the operator does not change when we change from one connection in the equivalence class to another. For example, if we consider the equivalence class of all torsion free connections, then the tensor Q is symmetric in its lower indices, i.e. . Therefore we can compute

where brackets denote skew symmetrization. This shows the invariance of the exterior derivative when acting on one forms. Equivalence classes of connections arise naturally in differential geometry, for example:

- in conformal geometry an equivalence class of connections is given by the Levi Civita connections of all metrics in the conformal class;

- in projective geometry an equivalence class of connection is given by all connections that have the same geodesics;

- in CR geometry an equivalence class of connections is given by the Tanaka-Webster connections for each choice of pseudohermitian structure

Examples

- The usual gradient operator acting on real valued functions on Euclidean space is invariant with respect to all Euclidean transformations.

- The differential acting on functions on a manifold with values in 1-forms (its expression is

in any local coordinates) is invariant with respect to all smooth transformations of the manifold (the action of the transformation on differential forms is just the pullback). - More generally, the exterior derivative

that acts on n-forms of any smooth manifold M is invariant with respect to all smooth transformations. It can be shown that the exterior derivative is the only linear invariant differential operator between those bundles. - The Dirac operator in physics is invariant with respect to the Poincaré group (if we choose the proper action of the Poincaré group on spinor valued functions. This is, however, a subtle question and if we want to make this mathematically rigorous, we should say that it is invariant with respect to a group which is a double cover of the Poincaré group)

- The conformal Killing equation

is a conformally invariant linear differential operator between vector fields and symmetric trace-free tensors.

Conformal invariance

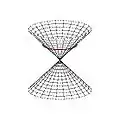

The sphere (here shown as a red circle) as a conformal homogeneous manifold.

The sphere (here shown as a red circle) as a conformal homogeneous manifold.

Given a metric

on , we can write the sphere as the space of generators of the nil cone

In this way, the flat model of conformal geometry is the sphere with and P the stabilizer of a point in . A classification of all linear conformally invariant differential operators on the sphere is known (Eastwood and Rice, 1987).[2]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Penrose and Rindler (1987). Spinors and Space Time. Cambridge Monographs on Mathematical Physics.

- ↑ M.G. Eastwood and J.W. Rice (1987). "Conformally invariant differential operators on Minkowski space and their curved analogues". Commun. Math. Phys. 109 (2): 207–228. Bibcode:1987CMaPh.109..207E. doi:10.1007/BF01215221. S2CID 121161256.

References

- Slovák, Jan (1993). Invariant Operators on Conformal Manifolds. Research Lecture Notes, University of Vienna (Dissertation).

{{cite book}}: External link in|title= - Kolář, Ivan; Michor, Peter; Slovák, Jan (1993). Natural operators in differential geometry (PDF). Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-03-30. Retrieved 2011-01-05.

- Eastwood, M. G.; Rice, J. W. (1987). "Conformally invariant differential operators on Minkowski space and their curved analogues". Commun. Math. Phys. 109 (2): 207–228. Bibcode:1987CMaPh.109..207E. doi:10.1007/BF01215221. S2CID 121161256.

- Kroeske, Jens (2008). "Invariant bilinear differential pairings on parabolic geometries". PhD Thesis from the University of Adelaide. arXiv:0904.3311. Bibcode:2009PhDT.......274K.

- ↑ Dobrev, Vladimir (1988). "Canonical construction of intertwining differential operators associated with representations of real semisimple Lie groups". Rep. Math. Phys. 25 (2): 159–181. Bibcode:1988RpMP...25..159D. doi:10.1016/0034-4877(88)90050-X.