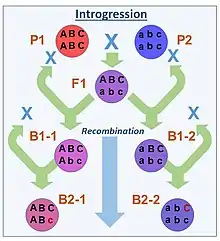

Introgressive hybridization, also known as introgression, is the flow of genetic material between divergent lineages via repeated backcrossing. In plants, this backcrossing occurs when an generation hybrid breeds with one or both of its parental species.

Source of variation

Although some genera of plants hybridize and introgress more easily than others, in certain scenarios, external factors may contribute to an increased rate of hybridization. The phenomenon known as Hybridization of the Habitat echoes this idea, explaining that disturbances in a natural habitat can lead to species which typically do not hybridize and backcross to do so with relative ease. Plant breeders also manipulate their subjects to hybridize in order to optimize their hardiness, appearance, or whatever desired traits they want to select for.[1] This type of hybridization has been particularly impactful for the production of many crop species, including but not limited to: certain types of rice, corn, wheat, barley, and rye. Natural introgression can occur with many genera and species, but manipulating the gene pool with artificial/forced introgression is useful for honing in on desired characteristics, such as drought tolerance or pest resistance.[2]

Background

In the early days of hybrid research, it was commonly believed that there was insufficient evidence of hybridization in nature because hybridization would mostly produce sterile or unfit offspring. Through experimentation and improved phylogenetic testing capabilities, we now see that the ability to produce fertile hybrid offspring varies by genus, within the plant kingdom.[3] A few examples of species with the capacity to produce fertile hybrids are given below.

Examples of natural introgression

Irises

One of the most significant early studies of plant hybridization involved three species of irises. Although they commonly form crosses where their natural habitats overlap, there is no evidence that Iris fulva, Iris hexagona, or Iris brevicaulis are closely related and their phenotypic differences (color/pattern/size) are distinct. Once introgression occurs, the resulting offspring display a wide array of color combinations, as well as varying flower size. Iris fulva shows a tendency for asymmetrical introgression, where it transfers more genetic material into hybrid offspring than either Iris hexagona or Iris brevicaulis.[4]

Sunflowers

Differential introgression of chloroplasts and nuclear genomes was first seen among the common sunflower (Helianthus annuus ssp. texanus). Within a particular region, the population showed differences in morphological features which indicated there may be hybridization with H. debilis ssp cucumenifolius. Researchers discovered that these H. a. texanus contained chloroplast DNA from H. d. cucumennfolius, indicating introgression had occurred in one direction.[5]

Poplars

Hybridization among poplars is common where ever populations overlap, however the degree of introgression varies greatly depending on the species. One study exploring the extent of introgression among three species of poplar trees (P. balsamifera, P. angustifolia and P. trichocarpa) conducted along the Rock Mountain range in the U.S. and Canada found extensive introgression in areas of species converge. Genomic sequencing even showed a trispecies hybrid in these overlapping areas. [6] Another study found a hybrid zone in Utah where there was a unidirectional flow of introgression between P. angustifolia and P. fremontii.[7]

Examples of artificial introgression

Wheat

Introgression has played a major role in the development of wheat for crop production. One of the ways crop species can be manipulated is by crossing them with wild type species. For instance, the wild wheat relative species Agropyron elongatum has been crossed and introgressed with the domesticated wheat Triticum aestivum. Consequently, the resulting hybrids have a higher water stress adaptation and higher root and shoot biomass. Both of these modifications can improve the fitness of the crop.[8]

Daffodils

Daffodils (genus Narcissus) are able to produce semi-fertile or fertile offspring, even from wide crosses. The ability of daffodils, such as the yellow trumpet Narcissi and Poets’ Narcissi to hybridize and backcross allows for the vast variety of options modern-day gardeners have to select from.[3] Although daffodils do hybridize and introgress in nature, artificial introgression allows for breeders to take species that are geographically separated and make unique crosses that would not appear naturally.

References

- ↑ Anderson, E.; Stebbins, G. L. (1954). "Hybridization as an Evolutionary Stimulus". Evolution. 8 (4): 378. doi:10.2307/2405784. JSTOR 2405784.

- ↑ Hao, Ming; Zhang, Lianquan; Ning, Shunzong; Huang, Lin; Yuan, Zhongwei; Wu, Bihua; Yan, Zehong; Dai, Shoufen; Jiang, Bo; Zheng, Youliang; Liu, Dengcai (2020-03-06). "The Resurgence of Introgression Breeding, as Exemplified in Wheat Improvement". Frontiers in Plant Science. 11: 252. doi:10.3389/fpls.2020.00252. ISSN 1664-462X. PMC 7067975. PMID 32211007.

- 1 2 Anderson, Edgar (1948). "Hybridization of the Habitat". Evolution. 2 (1): 1–9. doi:10.2307/2405610. JSTOR 2405610.

- ↑ Anderson, Edgar (1949). Introgressive hybridization. New York: J. Wiley. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.4553.

- ↑ Cruzan, Mitchell B. (2018). Evolutionary biology : a plant perspective. New York, NY. ISBN 978-0-19-088268-6. OCLC 1050360688.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Chhatre, Vikram E.; Evans, Luke M.; DiFazio, Stephen P.; Keller, Stephen R. (2018). "Adaptive introgression and maintenance of a trispecies hybrid complex in range-edge populations of Populus". Molecular Ecology. 27 (23): 4820–4838. doi:10.1111/mec.14820. ISSN 1365-294X. PMID 30071141. S2CID 51908670.

- ↑ Vanden Broeck, An; Villar, Marc; Van Bockstaele, Erik; VanSlycken, Jos (2005). "Natural hybridization between cultivated poplars and their wild relatives: evidence and consequences for native poplar populations". Annals of Forest Science. 62 (7): 601–613. doi:10.1051/forest:2005072. ISSN 1286-4560.

- ↑ Placido, Dante F.; Campbell, Malachy T.; Folsom, Jing J.; Cui, Xinping; Kruger, Greg R.; Baenziger, P. Stephen; Walia, Harkamal (2013-02-20). "Introgression of Novel Traits from a Wild Wheat Relative Improves Drought Adaptation in Wheat". Plant Physiology. 161 (4): 1806–1819. doi:10.1104/pp.113.214262. ISSN 0032-0889. PMC 3613457. PMID 23426195.