| |

| Formation | 23 June 1894 |

|---|---|

| Founder | Pierre de Coubertin Demetrios Vikelas |

| Type | Sports federation (Association organized under the laws of the Swiss Confederation) |

| Headquarters | Olympic House, Lausanne, Switzerland |

Membership | 107 active members, 41 honorary members, 206 individual National Olympic Committees |

Official language | French (reference language), English, and the host country's language when necessary |

| Thomas Bach[1] | |

Vice Presidents | Ng Ser Miang[1] John Coates Nicole Hoevertsz Juan Antonio Samaranch Salisachs |

Director General | Christophe De Kepper |

| Website | olympics |

| Anthem: Olympic Anthem Motto: Citius, Altius, Fortius – Communiter (Latin: Faster, Higher, Stronger – Together) | |

.jpg.webp)

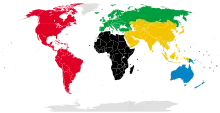

The International Olympic Committee (IOC; French: Comité international olympique, CIO) is a non-governmental sports organisation based in Lausanne, Switzerland.

It was founded in 1894 by Pierre de Coubertin and Demetrios Vikelas, it is the authority responsible for organising the modern (Summer, Winter, and Youth) Olympic Games.[2]

The IOC is the governing body of the National Olympic Committees (NOCs) and of the worldwide Olympic Movement, the IOC's term for all entities and individuals involved in the Olympic Games. As of 2020, 206 NOCs officially were recognised by the IOC. Its president is Thomas Bach.

Mission

Its stated mission is to promote Olympism throughout the world and to lead the Olympic Movement:[3]

- To encourage and support the promotion of ethics and good governance in sport;

- To support the education of youth through sport;

- To ensure that the spirit of fair play prevails and violence is avoided;

- To encourage and support the organization, development, and coordination of sport and sports competitions;

- To ensure the regular celebration of the Olympic Games;

- To cooperate with competent public or private organizations and authorities endeavouring to place sport at the service of humanity and thereby to promote peace;

- To take action to strengthen the unity, independence, political neutrality, and autonomy of the Olympic Movement;

- To encourage and support elected representatives of athletes, working with the IOC Athletes' Commission as their official representative;

- To encourage and support the promotion of women in sport in pursuit of equality between men and women;

- To protect clean athletes and the integrity of sport, by leading the fight against doping, and by taking action against all forms of manipulation of competitions and related corruption;

- To encourage and support measures relating to the medical care and health of athletes;

- To oppose any political or commercial abuse of sport and athletes;

- To encourage and support the efforts of sports organisations and public authorities to provide for the social and professional future of athletes;

- To encourage and support the development of sport for all;

- To encourage and support a responsible concern for environmental issues, to promote sustainable development in sport and to require that the Olympic Games are operated accordingly;

- To promote a positive legacy from the Olympic Games to the host cities, regions and countries;

- To encourage and support initiatives blending sport with culture and education;

- To encourage and support the activities of the International Olympic Academy ("IOA") and other institutions which dedicate themselves to Olympic education;

- To promote safe sport and the protection of athletes from all forms of harassment and abuse.

IOC member oath

All IOC members must swear to the following:

"Honoured to be chosen as a member of the International Olympic Committee, I fully accept all the responsibilities that this office brings: I promise to serve the Olympic Movement to the best of my ability. I will respect the Olympic Charter and accept the decisions of the IOC. I will always act independently of commercial and political interests as well as of any racial or religious consideration. I will fully comply with the IOC Code of Ethics. I promise to fight against all forms of discrimination and dedicate myself in all circumstances to promote the interests of the International Olympic Committee and Olympic Movement."

History

.jpg.webp)

The IOC was created by Pierre de Coubertin, on 23 June 1894 with Demetrios Vikelas as its first president. As of February 2022, its membership consists of 105 active members and 45 honorary members.[4] The IOC is the supreme authority of the worldwide modern Olympic Movement.

The IOC organizes the modern Olympic Games and Youth Olympic Games (YOG), held in summer and winter every four years. The first Summer Olympics was held in Athens, Greece, in 1896; the first Winter Olympics was in Chamonix, France, in 1924. The first Summer YOG was in Singapore in 2010, and the first Winter YOG was in Innsbruck in 2012.

Until 1992, both Summer and Winter Olympics were held in the same year. After that year, however, the IOC shifted the Winter Olympics to the even years between Summer Games to help space the planning of the two events from one another, and to improve the financial balance of the IOC, which receives a proportionally greater income in Olympic years.

Since 1995, the IOC has worked to address environmental health concerns resulting from hosting the games. In 1995, IOC President Juan Antonio Samaranch stated, "the International Olympic Committee is resolved to ensure that the environment becomes the third dimension of the organization of the Olympic Games, the first and second being sport and culture."[5] Acting on this statement, in 1996 the IOC added the "environment" as a third pillar to its vision for the Olympic Games.[6]

In 2000, the "Green Olympics" effort was developed by the Beijing Organizing Committee for the Beijing Olympic Games. The Beijing 2008 Summer Olympics executed over 160 projects addressing the goals of improved air quality and water quality, sustainable energy, improved waste management, and environmental education. These projects included industrial plant relocation or closure, furnace replacement, introduction of new emission standards, and more strict traffic control.[7]

In 2009, the UN General Assembly granted the IOC Permanent Observer status. The decision enables the IOC to be directly involved in the UN Agenda and to attend UN General Assembly meetings where it can take the floor. In 1993, the General Assembly approved a Resolution to further solidify IOC–UN cooperation by reviving the Olympic Truce.[8]

The IOC received approval in November 2015 to construct a new headquarters in Vidy, Lausanne. The cost of the project was estimated to stand at $156m.[9] The IOC announced on the 11th of February 2019 that the "Olympic House" would be inaugurated on the 23rd of June 2019 to coincide with its 125th anniversary.[10] The Olympic Museum remains in Ouchy, Lausanne.[11]

Since 2002, the IOC has been involved in several high-profile controversies including taking gifts, its DMCA take down request of the 2008 Tibetan protest videos, Russian doping scandals, and its support of the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics despite China's human rights violations documented in the Xinjiang Papers.

Detailed frameworks for environmental sustainability were prepared for the 2018 Winter Olympics, and 2020 Summer Olympics in PyeongChang, South Korea, and Tokyo.[12][13]

Organization

It is an association under the Swiss Civil Code (articles 60–79).

IOC Session

The IOC Session is the general meeting of the members of the IOC, held once a year in which each member has one vote. It is the IOC's supreme organ and its decisions are final.

Extraordinary Sessions may be convened by the President or upon the written request of at least one third of the members.

Among others, the powers of the Session are:

- To adopt or amend the Olympic Charter.

- To elect the members of the IOC, the Honorary President and the honorary members.

- To elect the President, the vice-presidents and all other members of the IOC Executive Board.

- To elect the host city of the Olympic Games.

Subsidiaries

- Olympic Foundation (Lausanne, Switzerland)

- IOC Television and Marketing Services S.A. (Lausanne, Switzerland)

- The Olympic Partner Programme (Lausanne, Switzerland)

- Olympic Broadcasting Services S.A. (Lausanne, Switzerland)

- Olympic Broadcasting Services S.L. (Madrid, Spain)

- Olympic Channel Services S.A. (Lausanne, Switzerland)

- Olympic Channel Services S.L. (Madrid, Spain)

- Olympic Foundation for Culture and Heritage (Lausanne, Switzerland)

- IOC Heritage Management

- Olympic Studies Centre

- Olympic Museum

- International Programmes for Arts, Culture and Education

- Olympic Solidarity (Lausanne, Switzerland)

IOC members

For most of its existence the IOC was controlled by members who were selected by other members. Countries that had hosted the Games were allowed two members. When named they became IOC members in their respective countries rather than representatives of their respective countries to the IOC.

Cessation of membership

Membership ends under the following circumstances:[14]

- Resignation: any IOC member may end their membership at any time by delivering a written resignation to the President.

- Non re-election: any IOC member ceases to be a member without further formality if they are not re-elected.

- Age limit: any IOC member ceases to be a member at the end of the calendar year during which they reach the age of 70 or 80. Any member who joined in the 1900s ceases to be a member at age 80 and any member who joined in the 2000s ceases to be a member at age 70.

- Failure to attend sessions or take active part in IOC work for two consecutive years.

- Transfer of domicile or of main centre of interests to a country other than their country at the time of their election.

- Members elected as active athletes cease to be a member upon ceasing to be a member of the IOC Athletes' Commission.

- Presidents and individuals holding an executive or senior leadership position within NOCs, world or continental associations of NOCs, IFs or associations of IFs, or other organisations recognised by the IOC cease to be a member upon ceasing to exercise the function they were exercising at the time of their election.

- Expulsion: an IOC member may be expelled by decision of the session if such member has betrayed their oath or if the Session considers that such member has neglected or knowingly jeopardised the interests of the IOC or acted in a way which is unworthy of the IOC.

Sports federations recognised by IOC

IOC recognises 82 international sports federations (IFs):[15]

- The 33 members of Association of Summer Olympic International Federations (ASOIF)[16]

- The 7 members of Association of International Olympic Winter Sports Federations (AIOWF)[17]

- The 42 members of Association of IOC Recognised International Sports Federations (ARISF)[18]

Honours

IOC awards gold, silver, and bronze medals for the top three competitors in each sporting event.

Other honours.

- Pierre de Coubertin medal: athletes who demonstrate a special spirit of sportsmanship[19]

- Olympic Cup: institutions or associations with a record of merit and integrity in developing the Olympic Movement[20]

- Olympic Order: individuals for exceptionally distinguished contributions to the Olympic Movement; superseded the Olympic Certificate[21]

- Olympic Laurel: individuals who promote education, culture, development, and peace through sport[22]

- Olympic town status: towns that have been particularly important for the Olympic Movement

Olympic marketing

_1985%252C_MiNr_Zusammendruck_2949.jpg.webp)

During the first half of the 20th century the IOC ran on a small budget.[23][24] As IOC president from 1952 to 1972, Avery Brundage rejected all attempts to link the Olympics with commercial interests.[25] Brundage believed that corporate interests would unduly impact the IOC's decision-making.[25] Brundage's resistance to this revenue stream left IOC organising committees to negotiate their own sponsorship contracts and use the Olympic symbols.[25]

When Brundage retired the IOC had US$2 million in assets; eight years later coffers had swollen, to US$45 million.[25] This was primarily due to a shift in ideology toward expansion of the Games through corporate sponsorship and the sale of television rights.[25] When Juan Antonio Samaranch was elected IOC president in 1980 his desire was to make the IOC financially independent.[24] Samaranch appointed Canadian IOC member Richard Pound to lead the initiative as Chairman of the "New Sources of Finance Commission".

In 1982 the IOC drafted International Sport and Leisure, a Swiss sports marketing company, to develop a global marketing programme for the Olympic Movement. ISL developed the programme, but was replaced by Meridian Management, a company partly owned by the IOC in the early 1990s. In 1989, a staff member at ISL Marketing, Michael Payne, moved to the IOC and became the organisation's first marketing director. ISL and then Meridian continued in the established role as the IOC's sales and marketing agents until 2002.[26][27] In collaboration with ISL Marketing and Meridian Management, Payne made major contributions to the creation of a multibillion-dollar sponsorship marketing programme for the organisation which, along with improvements in TV marketing and improved financial management, helped to restore the IOC's financial viability.[28][29][30]

Revenue

The Olympic Movement generates revenue through five major programmes.

- Broadcast partnerships, managed by the IOC.

- Commercial sponsorship, organised through the IOC's worldwide TOP programme.

- Domestic sponsorship, managed by the Organising Committees for the Olympic Games (OCOGs).

- Ticketing.

- Licensing programmes within host countries.

The OCOGs have responsibility for domestic sponsorship, ticketing and licensing programmes, under the direction of the IOC. The Olympic Movement generated a total of more than US$4 billion (€2.5 billion) in revenue during the Olympic quadrennium from 2001 to 2004.

- Revenue distribution

The IOC distributes some of its revenue to organisations throughout the Olympic Movement to support the staging of the Olympic Games and to promote worldwide sport development. The IOC retains approximately 10% of the Olympic marketing revenue for operational and administrative costs.[31] For the 2013–2016 period, IOC had revenues of about US$5.0 billion, of which 73% were from broadcasting rights and 18% were from Olympic Partners. The Rio 2016 organising committee received US$1.5 billion and the Sochi 2014 organising committee received US$833 million. National Olympic committees and international federations received US$739 million each.[31]

In July 2000, when the Los Angeles Times reported on how the IOC redistributes profits from sponsorships and broadcasting rights, historian Bob Barney stated that he had "yet to see matters of corruption in the IOC", but noted there were "matters of unaccountability".[32] He later noted that when the spotlight is on the athletes, it has "the power to eclipse impressions of scandal or corruption", with respect to the Olympic bid process.[33]

Organizing Committees for the Olympic Games

The IOC provides TOP programme contributions and broadcast revenue to the OCOGs to support the staging of the Olympic Games:

- TOP programme revenue: the two OCOGs of each Olympic quadrennium generally share approximately 50% of TOP programme revenue and value-in-kind contributions, with approximately 30% provided to the summer OCOG and 20% provided to the winter OCOG.

- Broadcast revenue: the IOC contributes 49% of the Olympic broadcast revenue for each Games to the OCOG. During the 2001–2004 Olympic quadrennium, the Salt Lake 2002 Organizing Committee received US$443 million, €395 million in broadcast revenue from the IOC, and the Athens 2004 Organizing Committee received US$732 million, €690 million.

- Domestic programme revenue: the OCOGs generate substantial revenue from the domestic marketing programmes that they manage within the host country, including domestic sponsorship, ticketing and licensing.

National Olympic Committees

NOCs receive financial support for training and developing their Olympic teams, Olympic athletes, and Olympic hopefuls. The IOC distributes TOP programme revenue to each NOC. The IOC also contributes Olympic broadcast revenue to Olympic Solidarity, an IOC organisation that provides financial support to NOCs with the greatest need. The continued success of the TOP programme and Olympic broadcast agreements has enabled the IOC to provide increased support for the NOCs with each Olympic quadrennium. The IOC provided approximately US$318.5 million to NOCs for the 2001–2004 quadrennium.

International Olympic Sports Federations

The IOC is the largest single revenue source for the majority of IOSFs, with contributions that assist them in developing their respective sports. The IOC provides financial support to the 28 IOSFs of Olympic summer sports and the seven IOSFs of Olympic winter sports. The continually increasing value of Olympic broadcasts has enabled the IOC to substantially increase financial support to IOSFs with each successive Games. The seven winter sports IFs shared US$85.8 million, €75 million in Salt Lake 2002 broadcast revenue.

Other organisations

The IOC contributes Olympic marketing revenue to the programmes of various recognised international sports organisations, including the International Paralympic Committee (IPC), and the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA).

Environmental concerns

The IOC requires cities bidding to host the Olympics to provide a comprehensive strategy to protect the environment in preparation for hosting, and following the conclusion of the Games.[34]

IOC approaches

The IOC has four major approaches to addressing environmental health concerns.

- IOC Sustainability and Legacy Commission focuses on how the IOC can improve the strategies and policies associated with environmental health throughout the process of hosting the Olympic Games.[35]

- Every candidate city must provide information on environmental health issues such as air quality and environmental impact assessments.

- Every host city is given the option to declare "pledges" to address specific or general environmental health concerns.

- Every host city must collaborate with the United Nations to work towards addressing environmental health objectives.[36]

Venue construction

Effects on air

Host cities have concerns about traffic congestion and air pollution, both of which can compromise air quality during and after venue construction.[37] Various air quality improvement measures are undertaken before and after each event. Traffic control is the primary method to reduce concentrations of air pollutants, including barring heavy vehicles.

Beijing Olympics

Research at the Beijing Olympic Games identified particulate matter – measured in terms of PM10 (the amount of aerodynamic diameter of particle ≤ 10 μm in a given amount of air) – as a top priority.[38][39] Particulate matter, along with other airborne pollutants, cause both serious health problems, such as asthma, and damage urban ecosystems. Black carbon is released into the air from incomplete combustion of carbonaceous fluids, contributing to climate change and injuring human health. Secondary pollutants such as CO, NOx, SO2, benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylenes (BTEX) are also released during construction.[40]

For the Beijing Olympics, vehicles not meeting the Euro 1 emission standards were banned, and the odd-even rule was implemented in the Beijing administrative area. Air quality improvement measures implemented by the Beijing government included replacing coal with natural gas, suspending construction and/or imposing strict dust control on construction sites, closing or relocating the polluting industrial plants, building long subway lines, using cleaner fluid in power plants, and reducing the activity by some of the polluting factories. There, levels of primary and secondary pollutants were reduced, and good air quality was recorded during the Beijing Olympics on most days. Beijing also sprayed silver iodide in the atmosphere to induce rain to remove existing pollutants from the air.[41]

Effects on soil

Soil contamination can occur during construction. The Sydney Olympic Games of 2000 resulted in improving a highly contaminated area known as Homebush Bay. A pre-Games study reported soil metal concentrations high enough to potentially contaminate groundwater. A remediation strategy was developed. Contaminated soil was consolidated into four containment areas within the site, which left the remaining areas available for recreational use. The site contained waste materials that then no longer posed a threat to surrounding aquifers.[42] In the 2006 Games in Torino, Italy, soil impacts were observed. Before the Games, researchers studied four areas that the Games would likely affect: a floodplain, a highway, the motorway connecting the city to Lyon, France, and a landfill. They analysed the chemicals in these areas before and after the Games. Their findings revealed an increase in the number of metals in the topsoil post-Games, and indicated that soil was capable of buffering the effects of many but not all heavy metals. Mercury, lead, and arsenic may have been transferred into the food chain.[43]

One promise made to Londoners for the 2012 Olympic Games was that the Olympic Park would be a "blueprint for sustainable living." However, garden allotments were temporarily relocated due to the building of the Olympic stadium. The allotments were eventually returned, however, the soil quality was damaged. Further, allotment residents were exposed to radioactive waste for five months prior to moving, during the excavation of the site for the Games. Other local residents, construction workers, and onsite archaeologists faced similar exposures and risks.[44]

Effects on water

The Olympic Games can affect water quality in several ways, including runoff and the transfer of polluting substances from the air to water sources through rainfall. Harmful particulates come from natural substances (such as plant matter crushed by higher volumes of pedestrian and vehicle traffic) and man-made substances (such as exhaust from vehicles or industry). Contaminants from these two categories elevate amounts of toxins in street dust. Street dust reaches water sources through runoff, facilitating the transfer of toxins to environments and communities that rely on these water sources.[37]

In 2013, researchers in Beijing found a significant relationship between the amount of PM2.5 concentrations in the air and in rainfall. Studies showed that rainfall had transferred a large portion of these pollutants from the air to water sources. Notably, this cleared the air of such particulates, substantially improving air quality at the venues.[45]

Controversies

| Olympic Games |

|---|

|

| Main topics |

| Games |

Amateurism and professionalism

De Coubertin was influenced by the aristocratic ethos exemplified by English public schools.[46] The public schools subscribed to the belief that sport formed an important part of education but that practicing or training was considered cheating.[46] As class structure evolved through the 20th century, the definition of the amateur athlete as an aristocratic gentleman became outdated.[46] The advent of the state-sponsored "full-time amateur athlete" of Eastern Bloc countries further eroded the notion of the pure amateur, as it put Western, self-financed amateurs at a disadvantage. The Soviet Union entered teams of athletes who were all nominally students, soldiers, or working in a profession, but many of whom were paid by the state to train on a full-time basis.[47] Nevertheless, the IOC held to the traditional rules regarding amateurism.[48]

Near the end of the 1960s, the Canadian Amateur Hockey Association (CAHA) felt their amateur players could no longer be competitive against the Soviet full-time athletes and other constantly improving European teams. They pushed for the ability to use players from professional leagues, but met opposition from the IIHF and IOC. At the IIHF Congress in 1969, the IIHF decided to allow Canada to use nine non-NHL professional hockey players[49] at the 1970 World Championships in Montreal and Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada.[50] The decision was reversed in January 1970 after Brundage declared that the change would put ice hockey's status as an Olympic sport in jeopardy.[49] In response, Canada withdrew from international ice hockey competition and officials stated that they would not return until "open competition" was instituted.[49][51]

Beginning in the 1970s, amateurism was gradually phased out of the Olympic Charter. After the 1988 Games, the IOC decided to make all professional athletes eligible for the Olympics, subject to the approval of the IFOSs.[52]

Bid controversies

1976 Winter Olympics

The Games were originally awarded to Denver on 12 May 1970, but a rise in costs led to Colorado voters' rejection on 7 November 1972, by a 3 to 2 margin, of a $5 million bond issue to finance the Games with public funds.[53][54]

Denver officially withdrew on 15 November, and the IOC then offered the Games to Whistler, British Columbia, Canada, but they too declined, owing to a change of government following elections.

Salt Lake City, Utah, a 1972 Winter Olympics final candidate who eventually hosted the 2002 Winter Olympics, offered itself as a potential host after Denver's withdrawal. The IOC declined Salt Lake City's offer and, on 5 February 1973, selected Innsbruck, the city that had hosted the Games twelve years earlier.

2002 Winter Olympics

A scandal broke on 10 December 1998, when Swiss IOC member Marc Hodler, head of the coordination committee overseeing the organisation of the 2002 Games, announced that several members of the IOC had received gifts from members of the Salt Lake City 2002 bid Committee in exchange for votes. Soon four independent investigations were underway: by the IOC, the United States Olympic Committee (USOC), the SLOC, and the United States Department of Justice. Before any of the investigations could get under way, SLOC co-heads Tom Welch and David Johnson both resigned their posts. Many others soon followed. The Department of Justice filed fifteen counts of bribery and fraud against the pair.

As a result of the investigation, ten IOC members were expelled and another ten were sanctioned.[55] Stricter rules were adopted for future bids, and caps were put into place as to how much IOC members could accept from bid cities. Additionally, new term and age limits were put into place for IOC membership, an Athlete's Commission was created and fifteen former Olympic athletes gained provisional membership status.

2008 Summer Olympics

In 2000, international human rights groups attempted to pressure the IOC to reject Beijing's bid to protest human rights in the People's Republic of China. One Chinese dissident was sentenced to two years in prison during an IOC tour.[56] After the city won the 2008 Summer Olympic Games, Amnesty International and others expressed concerns regarding the human rights situation. The second principle in the Fundamental Principles of Olympism, Olympic Charter states that "The goal of Olympism is to place sport at the service of the harmonious development of man, with a view to promoting a peaceful society concerned with the preservation of human dignity."[57] Amnesty International considered PRC policies and practices as violating that principle.[58]

Some days before the Opening Ceremonies, in August 2008, the IOC issued DMCA take down notices on Tibetan Protests videos on YouTube.[59] YouTube and the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) pushed back against the IOC, which then withdrew their complaint.

2016 and 2020 Summer Olympics

On 1 March 2016, Owen Gibson of The Guardian reported that French financial prosecutors investigating corruption in world athletics had expanded their remit to include the bidding and voting processes for the 2016 Summer Olympics and 2020 Summer Olympics.[60] The story followed an earlier report in January by Gibson, who revealed that Papa Massata Diack, the son of then-IAAF president Lamine Diack, appeared to arrange for "parcels" to be delivered to six IOC members in 2008 when Qatar was bidding for the 2016 Summer Olympic Games, though it failed to make it beyond the shortlist. Weeks later, Qatari authorities denied the allegations.[61] Gibson then reported that a €1.3m (£1m, $1.5m) payment from the Tokyo Olympic Committee team to an account linked to Papa Diack was made during Japan's successful race to host the 2020 Summer Games.[62] The following day, French prosecutors confirmed they were investigating allegations of "corruption and money laundering" of more than $2m in suspicious payments made by the Tokyo 2020 Olympic bid committee to a secret bank account linked to Diack.[63] Tsunekazu Takeda of the Tokyo 2020 bid committee responded on 17 May 2016, denying allegations of wrongdoing, and refused to reveal transfer details.[64] The controversy was reignited on 11 January 2019 after it emerged Takeda had been indicted on corruption charges in France over his role in the bid process.[65]

2022 Winter Olympics

In 2014, at the final stages of the bid process for 2022, Oslo, seen as the favourite, surprised with a withdrawal. Following a string of local controversies over the masterplan, local officials were outraged by IOC demands on athletes and the Olympic family. In addition, allegations about lavish treatment of stakeholders, including separate lanes to "be created on all roads where IOC members will travel, which are not to be used by regular people or public transportation", exclusive cars and drivers for IOC members. The differential treatment irritated Norwegians.[66][67][68] The IOC demanded "control over all advertising space throughout Oslo and the subsites during the Games, to be used exclusively by official sponsors."[68]

Human rights groups and governments criticised the committee for allowing Beijing to bid for the 2022 Winter Olympics. Some weeks before the Opening Ceremonies, the Xinjiang Papers were released, documenting abuses by the Chinese government against the Uyghur population in Xinjiang, documenting what many governments described as genocide.

Many government officials, notably those in the United States and the Great Britain, called for a boycott of the 2022 winter games. The IOC responded to concerns by saying that the Olympic Games must not be politicized.[69] Some Nations, including the United States, diplomatically boycotted games, which prohibited a diplomatic delegation from representing a nation at the games, rather than a full boycott that would have barred athletes from competing. In September 2021, the IOC suspended the Olympic Committee of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea, after they boycotted the 2020 Summer Olympics claiming "COVID-19 Concerns".

On 14 October 2021, vice-president of the IOC, John Coates, announced that the IOC had no plans to challenge the Chinese government on humanitarian issues, stating that the issues were "not within the IOC's remit".[70]

In December 2021, the United States House of Representatives voted unanimously for a resolution stating that the IOC had violated its own human rights commitments by cooperating with the Chinese government.[71] In January 2022, members of the U.S. House of Representatives unsuccessfully attempted to pass legislation to strip the IOC of its tax exemption status in the United States.[72]

Sex verification controversies

The IOC uses Sex verification to ensure participants compete only in events matching their sex.[73] Verifying the sex of Olympic participants dates back to ancient Greece when Kallipateira attempted to break Greek law by dressing as a man to enter the arena as a trainer. After she was discovered, a policy was erected wherein trainers, just as athletes, were made to appear naked in order to better assure all were male.[74] In more recent history, sex verification has taken many forms[75] and been subject to dispute.[76] Before sex testing, Olympic officials relied on "nude parades"[77] and doctor's notes.[76] Successful women athletes perceived to be masculine were most likely to be inspected.[76] In 1966, IOC implemented a compulsory sex verification process that took effect at the 1968 Winter Olympics where a lottery system was used to determine who would be inspected with a Barr body test.[77][76] The scientific community found fault with this policy. The use of the Barr body test was evaluated by fifteen geneticists who unanimously agreed it was scientifically invalid.[75] By the 1970s this method was replaced with PCR testing, as well as evaluating factors such as brain anatomy and behaviour.[73] Following continued backlash against mandatory sex testing, the IOC's Athletes' Commission's opposition ended of the practice in 1999.[75] Although sex testing was no longer mandated, women who did not present as feminine continued to be inspected based on suspicion. This started at 2000 Summer Olympics and remained in use until the 2010 Winter Olympics.[75] By 2011 the IOC created a Hyperandrogenism Regulation, which aimed to standardize natural testosterone levels in women athletes.[77] This transition in sex testing was to assure fairness within female events. This was due to the belief that higher testosterone levels increased athletic ability and gave unfair advantages to intersex and transgender competitors.[73][77] Any female athlete flagged for suspicion and whose testosterone surpassed regulation levels was prohibited from competing until medical treatment brought their hormone levels within standard levels.[73][77] It has been argued by press,[78] scholars,[79] and politicians[73] that some ethnicities are disproportionately impacted by this regulation and that the rule excludes too many.[73][78][79] The most notable cases of bans testing results are: Maria José Martínez-Patiño (1985),[80] Santhi Soundarajan (2006),[80] Caster Semenya (2009),[73] Annet Negesa (2012),[81] and Dutee Chand (2014).[77]

Before the 2014 Asian Games, Indian athlete Dutee Chand was banned from competing internationally having been found to be in violation of the Hyperandrogenism Regulation.[77] Following the denial of her appeal by the Court of Arbitration for Sport, the IOC suspended the policy for the 2016 Summer Olympics and 2018 Winter Olympics.[77]

Nagano 1998

Eight years after the 1998 Winter Olympics, a report ordered by the Nagano region's governor said the Japanese city provided millions of dollars in an "illegitimate and excessive level of hospitality" to IOC members, including US$4.4 million spent on entertainment.[82] Earlier reports put the figure at approximately US$14 million. The precise figures are unknown: after the IOC asked that the entertainment expenditures not be made public Nagano destroyed its financial records.[83][84]

2010 Shame On You Awards

In 2010, the IOC was nominated for the Public Eye Awards. This award seeks to present "shame-on-you-awards to the nastiest corporate players of the year".[85]

London 2012 and the Munich massacre

Before the start of the 2012 Summer Olympic Games, the IOC decided not to hold a minute of silence to honour the 11 Israeli Olympians who were killed 40 years prior in the Munich massacre. Jacques Rogge, the then-IOC President, said it would be "inappropriate" to do so. Speaking of the decision, Israeli Olympian Shaul Ladany, who had survived the Munich Massacre, commented: "I do not understand. I do not understand, and I do not accept it".[86]

Wrestling

In February 2013, the IOC excluded wrestling from its core Olympic sports for the Summer Olympic programme for the 2020 Summer Olympics, because the sport did offer equal opportunities for men and women. This decision was attacked by the sporting community, given the sport's long traditions.[87] This decision was later overturned, after a reassessment. Later, the sport was placed among the core Olympic sports, which it will hold until at least 2032.[88]

Russian doping

Media attention began growing in December 2014 when German broadcaster ARD reported on state-sponsored doping in Russia, comparing it to doping in East Germany. In November 2015, the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) published a report and the World Athletics (then known as the IAAF) suspended Russia indefinitely from world track and field events. The United Kingdom Anti-Doping agency later assisted WADA with testing in Russia. In June 2016, they reported that they were unable to fully carry out their work and noted intimidation by armed Federal Security Service (FSB) agents.[89] After a Russian former lab director made allegations about the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi, WADA commissioned an independent investigation led by Richard McLaren. McLaren's investigation found corroborating evidence, concluding in a report published in July 2016 that the Ministry of Sport and the FSB had operated a "state-directed failsafe system" using a "disappearing positive [test] methodology" (DPM) from "at least late 2011 to August 2015".[90]

In response to these findings, WADA announced that RUSADA should be regarded as non-compliant with respect to the World Anti-Doping Code and recommended that Russia be banned from competing at the 2016 Summer Olympics.[91] The IOC rejected the recommendation, stating that a separate decision would be made for each athlete by the relevant IF and the IOC, based on the athlete's individual circumstances.[92][93] One day prior to the opening ceremony, 270 athletes were cleared to compete under the Russian flag, while 167 were removed because of doping.[94] In contrast, the entire Kuwaiti team was banned from competing under their own flag (for a non-doping related matter).[95][96]

In contrast to the IOC, the IPC voted unanimously to ban the entire Russian team from the 2016 Summer Paralympics, having found evidence that the DPM was also in operation at the 2014 Winter Paralympics.[97]

On 5 December 2017, the IOC announced that the Russian Olympic Committee had been suspended effective immediately from the 2018 Winter Olympics. Athletes who had no previous drug violations and a consistent history of drug testing were allowed to compete under the Olympic Flag as an "Olympic Athlete from Russia" (OAR).[98] Under the terms of the decree, Russian government officials were barred from the Games, and neither the country's flag nor anthem would be present. The Olympic Flag and Olympic Anthem would be used instead,[99] and on 20 December 2017 the IOC proposed an alternate uniform logo.[100]

On 1 February 2018, the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) found that the IOC provided insufficient evidence for 28 athletes, and overturned their IOC sanctions.[101] For 11 other athletes, the CAS decided that there was sufficient evidence to uphold their Sochi sanctions, but reduced their lifetime bans to only the 2018 Winter Olympics.[102] The IOC said in a statement that "the result of the CAS decision does not mean that athletes from the group of 28 will be invited to the Games. Not being sanctioned does not automatically confer the privilege of an invitation" and that "this [case] may have a serious impact on the future fight against doping". The IOC found it important to note that the CAS Secretary General "insisted that the CAS decision does not mean that these 28 athletes are innocent" and that they would consider an appeal against the court's decision.[103][104] Later that month, the Russian Olympic Committee was reinstated by the IOC, despite numerous failed drug tests by Russian athletes in the 2018 Olympics.[105][106] The Russian Anti-Doping Agency was re-certified in September, despite the Russian rejection of the McLaren Report.[107]

2018 plebiscite in Taiwan

On 24 November 2018, the Taiwanese government held a referendum over a change in the naming of their National Olympic Committee, from "Chinese Taipei," a name agreed to in 1981 by the People's Republic of China in the Nagoya Protocol, which denies the Republic of China's legitimacy, to simply "Taiwan", after the main island in the Free Area. In the immediate days prior to the referendum, the IOC and the PRC government, issued a threatening statement, suggesting that if the team underwent the name change, the IOC had the legal right to make a "suspension of or forced withdrawal," of the team from the 2020 Summer Olympics.[108][109] In response to the allegations of election interference, the IOC stated, "The IOC does not interfere with local procedures and fully respects freedom of expression. However, to avoid any unnecessary expectations or speculations, the IOC wishes to reiterate that this matter is under its jurisdiction.[110]" Subsequently, with a significant PRC pressure, the referendum failed in Taiwan with 45% to 54%.

Peng Shuai disappearance

In November 2021, the IOC was again criticized by Human Rights Watch (HRW) and others for its response to the 2021 disappearance of Peng Shuai, following her publishing of sexual assault allegations against a former Chinese vice premier, and high-ranking member of the Chinese Communist Party, Zhang Gaoli.[111] The IOC's response was internationally criticized as complicit in assisting the Chinese government to silence Peng's sexual assault allegations.[112][113] Zhang Gaoli previously led the Beijing bidding committee to host the 2022 Winter Olympics.[114]

Fencing handshaking controversy

In July 2020 (and reconfirmed by FIE public notice in September 2020 and in January 2021), by public written notice the FIE had replaced its previous handshake requirement with a "salute" by the opposing fencers, and written in its public notice that handshakes were "suspended until further notice."[115][116][117][118][119] Nevertheless, in July 2023 when Ukrainian four-time world fencing individual sabre champion Olga Kharlan was disqualified at the World Fencing Championships by the Fédération Internationale d'Escrime for not shaking the hand of her defeated Russian opponent, although Kharlan instead offered a tapping of blades in acknowledgement, Thomas Bach stepped in the next day.[120][121] As President of the IOC, he sent a letter to Kharlan in which he expressed empathy for her, and wrote that in light of the situation she was guaranteed a spot in the 2024 Summer Olympics.[122][123] He wrote further: "as a fellow fencer, it is impossible for me to imagine how you feel at this moment. The war against your country, the suffering of the people in Ukraine, the uncertainty around your participation at the Fencing World Championships ... and then the events which unfolded yesterday – all this is a roller coaster of emotions and feelings. It is admirable how you are managing this incredibly difficult situation, and I would like to express my full support to you. Rest assured that the IOC will continue to stand in full solidarity with the Ukrainian athletes and the Olympic community of Ukraine."[124]

Russian invasion of Ukraine

On 12 October 2023, the International Olympic Committee issued a statement stating that after Russia began its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the Russian Olympic Committee unilaterally transferred four regions that were originally under the jurisdiction of the National Olympic Committee of Ukraine: Donetsk Oblast, Luhansk Oblast, Kherson Oblast, Zaporizhzhia Oblast were included as members of their own, so the International Olympic Committee announced the suspension of the membership of the Russian Olympic Committee with immediate effect.[125]

Current IOC Executive Board

| Designation | Name | Country |

|---|---|---|

| President | Thomas Bach | |

| Vice Presidents | Ng Ser Miang | |

| John Coates | ||

| Nicole Hoevertsz | ||

| Juan Antonio Samaranch Salisachs | ||

| Executive Members | Mikaela Cojuangco Jaworski | |

| Gerardo Werthein | ||

| Robin E. Mitchell | ||

| Denis Oswald | ||

| Kristin Kloster Aasen | ||

| Emma Terho | ||

| Nenad Lalović | ||

| Ivo Ferriani | ||

| Prince Feisal Al Hussein | ||

| Kirsty Coventry | ||

| Director General | Christophe De Kepper |

IOC Commissions

| Commission | Chairperson | Country |

|---|---|---|

| IOC Athletes' Commission | Emma Terho | |

| IOC Athletes' Entourage Commission | Sergey Bubka | |

| IOC Audit Committee | Pierre-Olivier Beckers-Vieujant | |

| IOC Communication Commission | Anant Singh | |

| IOC Future Host Winter Commission 2030 Winter Olympics | Octavian Morariu | |

| IOC Future Host Summer Commission 2030 Summer Youth Olympics (YOG) | Kolinda Grabar-Kitarovic | |

| IOC Coordination Commission Brisbane 2032 | Kirsty Coventry | |

| IOC Coordination Commission Los Angeles 2028 | Nicole Hoevertsz | |

| IOC Coordination Commission Dakar 2026 (YOG) | Kirsty Coventry | |

| IOC Coordination Commission Milano-Cortina 2026 | Kristin Kloster Aasen | |

| IOC Coordination Commission Paris 2024 | Pierre-Olivier Beckers-Vieujant | |

| IOC Coordination Commission Gangwon 2024 (YOG) | Zhang Hong | |

| IOC Culture and Olympic Heritage Commission | Khunying Patama Leeswadtrakul | |

| IOC Digital and Technology Commission | Gerardo Werthein | |

| IOC Ethics Commission | Ban Ki-moon | |

| IOC Finance Commission | Ng Ser Miang | |

| IOC Members Election Commission | Anne, Princess Royal | |

| IOC Legal Affairs Commission | John Coates | |

| IOC Marketing Commission | Jiri Kejval | |

| IOC Medical and Scientific Commission | Uğur Erdener | |

| IOC Olympic Channel Commission | Richard Carrión | |

| IOC Olympic Education Commission | Mikaela Cojuangco Jaworski | |

| IOC Olympic Programme Commission | Karl Stoss | |

| IOC Olympic Solidarity Commission | Robin E. Mitchell | |

| IOC Olympism 365 Commission | Auvita Rapilla | |

| IOC Commission for Public Affairs and Social Development Through Sport | Luis Alberto Moreno | |

| IOC Sport and Active Society Commission | Sari Essayah | |

| IOC Sustainability and Legacy Commission | Albert II, Prince of Monaco | |

| IOC Women in Sport Commission | Lydia Nsekera | |

| IOC Communications Director | Mark Adams |

The Olympic Partner programme

The Olympic Partner (TOP) sponsorship programme includes the following commercial sponsors of the Olympic Games.

- Airbnb

- Allianz

- Alibaba Group

- Atos

- Bridgestone

- Coca-Cola

- Intel

- Mengniu Dairy (joint partnership with Coca-Cola)

- Omega SA (previously The Swatch Group, its parent company)

- Panasonic

- Procter & Gamble

- Samsung

- Toyota

- Visa Inc.

See also

- Association of International Olympic Winter Sports Federations (AIOWF)

- Association of IOC Recognised International Sports Federations (ARISF)

- Association of Summer Olympic International Federations (ASOIF)

- International Academy of Sport Science and Technology (AISTS)

- International Committee of Sports for the Deaf (ICSD)

- International Paralympic Committee (IPC)

- International University Sports Federation (FISU)

- Global Association of International Sports Federations (GAISF)

- FICTS (Fédération Internationale Cinéma Télévision Sportifs) (Organisation recognised by the IOC)

- List of IOC meetings

- Olympic Congress

References

- 1 2 "IOC". International Olympic Committee. 29 January 2023. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- ↑ Roger Bartlett, Chris Gratton, Christer G. Rolf Encyclopedia of International Sports Studies. Routledge, 2012, p. 678

- ↑ "Olympic Charter" (PDF). Olympics.com. International Olympic Committee. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 November 2021. Retrieved 11 January 2023.

- ↑ "IOC Members List". Archived from the original on 5 August 2016. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ↑ Jagemann, H. (2003). "Sport and the Environment: Ways toward Achieving the Sustainable Development of Sport". The Sports Journal. Archived from the original on 27 October 2016. Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- ↑ Beyer S. (2006). The green Olympic Movement: Beijing 2008. Chinese Journal of International Law, 5:2, 423–440.

- ↑ Chen Y, Jin GZ, Kumar N, Shi G. (2012). The Promise of Beijing: Evaluating the Impact of the 2008 Olympic Games on Air Quality. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 66, 424–433.

- ↑ "Cooperation with the UN". 21 June 2016. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ↑ swissinfo.ch, S. W. I.; Corporation, a branch of the Swiss Broadcasting (25 November 2015). "Lausanne gives green light to new IOC headquarters". SWI swissinfo.ch. Archived from the original on 12 February 2019. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- ↑ "OLYMPIC HOUSE". IOC. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ↑ "Olympic House to officially open on Olympic Day – Olympic News". International Olympic Committee. 11 February 2019. Archived from the original on 12 February 2019. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- ↑ "Creating a New Horizon for Sustainable 2018 PyeongChang Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games: Furthering Benefits to Human and Nature" (PDF). The PyeongChang Organizing Committee for the 2018 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 October 2016. Retrieved 26 October 2016.

- ↑ "Tokyo 2020 Olympic and Paralympic Games High-level Sustainability Plan" (PDF). The Tokyo Organizing Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 October 2016. Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- ↑ Source: Olympic Charter, in force as from 1 September 2004.

- ↑ "International federations". olympic.org. Archived from the original on 22 August 2012. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- ↑ "ASOIF – Members". asoif.com. Archived from the original on 21 August 2016. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ↑ "AIOWF -Members". olympic.org. Archived from the original on 29 June 2012. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- ↑ "Who We Are – ARISF (Association of IOC Recognized Sports Federation)". ARISF. 2018. Archived from the original on 11 August 2016. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ "These Olympic Runners Just Won a Major Honor". Time. Archived from the original on 7 February 2019. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- ↑ "the olympic cup – Google Search". google.com. Archived from the original on 8 April 2022. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- ↑ "IOC President awards the Olympic Order to PyeongChang 2018 organisers". International Olympic Committee. 5 February 2019. Archived from the original on 12 March 2021. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- ↑ "Kip Keino to receive Olympic Laurel distinction" (Press release). Lausanne: International Olympic Committee. 4 August 2016. Archived from the original on 25 August 2018. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

Kip Keino (KEN) is the first ever recipient of the Olympic Laurel, a distinction created by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) to honour an outstanding individual for their achievements in education, culture, development and peace through sport..

- ↑ "Issues of the Olympic Games". Olympic Primer. LA84 Foundation of Los Angeles. Archived from the original on 25 April 2009. Retrieved 30 March 2009.

- 1 2 Buchanon & Mallon 2006, p. ci.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Cooper-Chen 2005, p. 231.

- ↑ "IOC Marketing Supremo: Smile, Beijing". china.org.cn. 6 August 2008. Archived from the original on 19 February 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ↑ "How the IOC took on Nike in Atlanta". Sports Business Journal Daily. Sports Business Journal. 11 July 2005. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ↑ "London Bid 'Has Improved'". Sporting Life. Archived from the original on 15 May 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ↑ "Boost for London's Olympic Bid". RTÉ Sport. 14 February 2005. Archived from the original on 21 September 2005. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ↑ Campbell, Struan (22 October 2008). "Payne – London 2012 to tap fountain of youth". Sportbusiness.com. Archived from the original on 7 January 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- 1 2 Funding Archived 8 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine – IOC. Retrieved on 7 August 2021

- ↑ Abrahamson, Alan; Wharton, David (30 July 2000). "IOC: A tangled web of wealth, mystery". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri. p. 24.

- ↑ "Sun sets on Salt Lake City". Herald News. Passaic County, New Jersey. 25 February 2002. p. A1.; "Games (Continued From A1)". Herald News. Passaic County, New Jersey. 25 February 2002. p. A6.

- ↑ "Host City Contract" (PDF). IOC. 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 August 2011. Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- ↑ "Sustainability And Legacy Commission". International Olympic Committee. 10 June 2021. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 23 June 2021.

- ↑ "The 2016 Olympic Games: Health, Security, Environmental, and Doping Issues" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. 8 August 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 August 2016. Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- 1 2 Qiao Q, Zhang C, Huang B, Piper JDA. (2011). Evaluating the environmental quality impact of the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games: magnetic monitoring of street dust in Beijing Olympic Park. Geophysical Journal International, Vol. 187; 1222.

- ↑ Chena DS, Chenga SY, Liub L, Chenc T, Guoa XR. (2007). An integrated MM5–CMAQ modeling approach for assessing transboundary PM10 contribution to the host city of 2008 Olympic summer games—Beijing, China. Atmospheric environment. Vol. 41; 1237–1250.

- ↑ Wang X et al. (2009). Evaluating the air quality impacts of the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games: On-road emission factors and black carbon profiles. Atmospheric environment. Vol. 43; 4535–4543.

- ↑ Wang T et al. (2010). Air quality during the 2008 Beijing Olympics: secondary pollutants and regional impact. Atmos. Chem. Phys. Vol. 10; 7603–7615.

- ↑ Coonan, Clifford (11 August 2008). "How Beijing used rockets to keep opening ceremony dry". The Independent. Retrieved 30 November 2023.

- ↑ Suh J-Y, Birch G. F., Hughes K., Matthai C. (2004) Spatial distribution and source of heavy metals in reclaimed lands of Homebush Bay: the venue of the 2000 Olympic Games, Sydney, New South Wales. Australian Journal of Earth Sciences. Vol. 51: 53–66.

- ↑ Scalenghe, Riccardo; Fasciani, Gabriella (2008). "Soil Heavy Metals Patterns in the Torino Olympic Winter Games Venue (E.U.)" (PDF). Soil and Sediment Contamination. 17 (3): 205–220. doi:10.1080/15320380802006905. S2CID 94537225. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 July 2018.

- ↑ Sadd D. (2012). Not all Olympic 'events' are good for the health just ask the previous occupants of the Manor Road. Allotments Perspectives in Public Health. Vol. 132; 2, 62–63.[SIC]

- ↑ Ouyang W. 313.

- 1 2 3 Eassom, Simon (1994). Critical Reflections on Olympic Ideology. Ontario: The Centre for Olympic Studies. pp. 120–123. ISBN 0-7714-1697-0.

- ↑ Benjamin, Daniel (27 July 1992). "Traditions Pro Vs. Amateur". Time. Archived from the original on 2 September 2009. Retrieved 18 March 2009.

- ↑ Schantz, Otto. "The Olympic Ideal and the Winter Games Attitudes Towards the Olympic Winter Games in Olympic Discourses—from Coubertin to Samaranch" (PDF). Comité International Pierre De Coubertin. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 May 2013. Retrieved 13 September 2008.

- 1 2 3 Podnieks & Szemberg 2008, Story #17–Protesting amateur rules, Canada leaves international hockey Archived 10 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Podnieks & Szemberg 2008, Story #40–Finally, Canada to host the World Championship Archived 10 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Summit Series '72 Summary". Hockey Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on 7 August 2008. Retrieved 2 March 2009.

- ↑ "Amateurism". USA Today. 12 July 1999. Archived from the original on 23 February 2002. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ↑ "Colorado only state ever to turn down Olympics". Denver.rockymountainnews.com. Archived from the original on 1 June 2009. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ↑ "The Games that got away – 2002 Winter Olympics coverage". Deseretnews.com. Archived from the original on 1 September 2010. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ↑ "Samaranch reflects on bid scandal with regret". 2002 Winter Olympics coverage. Deseret News Archives. 19 May 2001. Archived from the original on 26 February 2002.

- ↑ Bodeen, Christopher (25 February 2001). "Beijing opens itself up to Olympic inspectors". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on 15 November 2007.

- ↑ "Olympic Charter, in force as from 1 September 2004" (PDF). International Olympic Committee. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 July 2011.

- ↑ "People's Republic of China: The Olympics countdown – failing to keep human rights promises". Amnesty International. 21 September 2006. Archived from the original on 18 March 2007.

- ↑ IOC backs off DMCA take-down for Tibet protest "Video: IOC backs off DMCA take-down for Tibet protest | the Industry Standard". Archived from the original on 18 August 2008. Retrieved 15 August 2008.

- ↑ Gibson, Exclusive by Owen (1 March 2016). "French police widen corruption investigation to 2016 and 2020 Olympic bids". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 12 February 2019. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- ↑ Gibson, Owen (11 January 2016). "Disgraced athletics chief's son 'arranged parcels' for senior IOC members". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 12 February 2019. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- ↑ Gibson, Exclusive by Owen (11 May 2016). "Tokyo Olympics: €1.3m payment to secret account raises questions over 2020 Games". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 12 February 2019. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- ↑ Gibson, Owen (12 May 2016). "French financial prosecutors confirm investigation into Tokyo 2020 bid". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 12 February 2019. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- ↑ Gibson, Owen (17 May 2016). "Tokyo 2020 Olympic bid leader refuses to reveal Black Tidings details". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 4 June 2016. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- ↑ Panja, Tariq; Tabuchi, Hiroko (11 January 2019). "Japan's Olympics Chief Faces Corruption Charges in France". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 3 January 2022. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- ↑ Mathis-Lilley, Ben (2 October 2014). "The IOC Demands That Helped Push Norway Out of Winter Olympic Bidding Are Hilarious". Slate Magazine. Archived from the original on 20 May 2022. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- ↑ "IOC demands smiles, ridiculous perks ahead of 2022 Olympic bid". CBSSports.com. October 2014. Archived from the original on 28 May 2022. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- 1 2 "IOC hits out as Norway withdraws Winter Olympic bid". Financial Times. 2 October 2014. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- ↑ "IOC is no 'super world government' to solve China issues, says Bach". Reuters. 12 March 2021. Archived from the original on 10 October 2021. Retrieved 10 October 2021.

- ↑ "IOC's Coates rules out pressuring China over human rights". Reuters. 13 October 2021. Archived from the original on 13 October 2021. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- ↑ Zengerle, Patricia (9 December 2021). "U.S. House passes measure clamping down on products from China's Xinjiang region". Reuters. Archived from the original on 25 December 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- ↑ Mulinda, Norah (19 January 2022). "U.S. Lawmakers Propose Bill to Strip IOC of Its Tax-Exempt Status". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 21 January 2022. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Pastor, Aaren (2019). "Unwarranted and Invasive Scrutiny: Caster Semenya, Sex-Gender Testing and the Production of Woman In 'Women's' Track and Field". Feminist Review. 122: 1–15. doi:10.1177/0141778919849688. S2CID 204379565 – via SAGE Journals.

- ↑ Rupert, James L. (2011). "Genitals to genes: the history and biology of gender verification in the Olympics". Canadian Bulletin of Medical History. 28 (2): 339–365. doi:10.3138/cbmh.28.2.339. PMID 22164600 – via GALE ONEFILE.

- 1 2 3 4 Krieger, Jörg; Parks Pieper, Lindsay; Ritchie, Ian (2019). "Sex, drugs and science: the IOC's and IAAF's attempts to control fairness in sport". Sport in Society. 22 (9): 1555–1573. doi:10.1080/17430437.2018.1435004. S2CID 148683831 – via Taylor & Francis Online.

- 1 2 3 4 Parks Pieper, Lindsay (2018). "First, they qualified for the Olympics. Then they had to prove their sex". The Washington Post.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Pape, Madeleine (2019). "Expertise and Non-Binary Bodies: Sex, Gender and the Case of Dutee Chand". Body & Society. 25 (4): 3–28. doi:10.1177/1357034X19865940. S2CID 201403008 – via SAGE journals.

- 1 2 Burnett, Cora (2019). "South African Newspapers' Constructions of the Caster Semenya Saga through Political Cartoons". South African Review of Sociology. 50 (2): 62–84. doi:10.1080/21528586.2019.1699440. S2CID 213623805 – via Taylor & Francis Online.

- 1 2 Mahomed, S; Dhai, A (2019). "The Caster Semenya ordeal – prejudice, discrimination and racial bias". South African Medical Journal. 109 (8): 548–551. doi:10.7196/SAMJ.2019.v109i8.14152. PMID 31456545. S2CID 201175909 – via SciELO South Africa.

- 1 2 Parks Pieper, Lindsay (2014). "Sex Testing and the Maintenance of Western Femininity in International Sport". International Journal of the History of Sport. 31 (13): 1557–1576. doi:10.1080/09523367.2014.927184. S2CID 144448974 – via Taylor & Francis Online.

- ↑ Bruce, Kidd (2020). "The IOC must rule out sex testing at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics". Globe & Mail.

- ↑ "Mainichi Daily News ends its partnership with MSN, takes on new Web address". Mdn.mainichi-msn.co.jp. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- ↑ Jordan, Mary; Sullivan, Kevin (21 January 1999), "Nagano Burned Documents Tracing '98 Olympics Bid", The Washington Post, pp. A1, archived from the original on 25 June 2022, retrieved 20 August 2016

- ↑ Macintyre, Donald (1 February 1999). "Japan's Sullied Bid". Time Magazine. Archived from the original on 26 June 2022. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- ↑ "The Public Eye Awards Nominations 2010". Public Eye. Archived from the original on 28 September 2010. Retrieved 17 February 2010.

- ↑ James Montague (5 September 2012). "The Munich massacre: A survivor's story". CNN. Archived from the original on 21 June 2018. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ↑ "Wrestling dropped from 2020 Games". Espn.go.com. 14 February 2013. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- ↑ "Wrestling reinstated for Tokyo 2020 | Olympics News". ESPN.co.uk. 8 September 2013. Archived from the original on 19 September 2014. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- ↑ "Update on the status of Russia testing" (PDF). WADA. June 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 January 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ↑ "McLaren Independent Investigations Report into Sochi Allegations". WADA. 18 July 2016. Archived from the original on 6 December 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ↑ "WADA Statement: Independent Investigation confirms Russian State manipulation of the doping control process". WADA. 18 July 2016. Archived from the original on 3 December 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ↑ "Decision of the IOC Executive Board concerning the participation of Russian athletes in the Olympic Games Rio 2016". IOC. 24 July 2016. Archived from the original on 30 December 2017. Retrieved 24 July 2016.

- ↑ "IOC sets up 3-person panel to rule on Russian entries". San Diego Tribune. 30 July 2016. Archived from the original on 31 July 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ↑ "Rio 2016: 270 Russians cleared to compete at Olympic Games". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 4 August 2016. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- ↑ "Exclusive: Pound confident Russian athletes will be found guilty of Sochi 2014 doping despite IOC inaction". insidethegames.biz. 5 June 2017. Archived from the original on 17 September 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ↑ "Doping pressure mounts on IOC at German parliament". dw.com. 27 April 2017. Archived from the original on 17 September 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ↑ "The IPC suspends the Russian Paralympic Committee with immediate effect". ESPN. 15 March 2017. Archived from the original on 7 December 2017. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- ↑ Ruiz, Rebecca C.; Panja, Tariq (5 December 2017). "Russia Banned From Winter Olympics by I.O.C." The New York Times. Archived from the original on 17 December 2017. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- ↑ "IOC suspends Russian NOC and creates a path for clean individual athletes to compete in Pyeongchang 2018 under the Olympic Flag" (Press release). International Olympic Committee. 5 December 2017. Archived from the original on 24 April 2020. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- ↑ "IOC's OAR implementation group releases guidelines for uniforms accessories and equipment's". olympic.org. 20 December 2017. Archived from the original on 23 March 2018. Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- ↑ Lowell, Hugo (1 February 2018). "Winter Olympics: Twenty-eight Russians have lifetime doping bans overturned". inews.co.uk. Archived from the original on 12 February 2019. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- ↑ "ICAS's Coates responds to Bach over IOC concerns". USA Today. Associated Press. 4 February 2018. Archived from the original on 3 October 2018. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

- ↑ Aspin, Guy (2 February 2018). "Wada: Clearing Russian athletes may cause 'dismay and frustration'". The Independent. Archived from the original on 3 October 2018. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

- ↑ "IOC Statement on CAS decision". Olympic Games. 1 February 2018. Archived from the original on 1 February 2018. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

- ↑ Lowell, Hugo (23 February 2018). "Tensions rise over reinstatement of Russia at Winter Olympics". inews.co.uk. Archived from the original on 12 February 2019. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- ↑ Kelner, Martha (28 February 2018). "Russia's Olympic membership restored by IOC after doping ban". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 September 2018. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ↑ "Russia reinstated by WADA, ending nearly 3-year suspension after doping scandal". USA Today. Archived from the original on 3 October 2018. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ↑ Bai, Ari (3 December 2018). "Why The ROC Should Compete as Taiwan in the 2020 Olympics". The Free China Post. Archived from the original on 13 April 2020. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ↑ Deaeth, Duncan (20 November 2018). "WIOC threatens to disbar Chinese Taipei Olympic Committee". Taiwan News. Archived from the original on 5 August 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ↑ "International Olympic Committee warns Taiwan against name-change that would rile Beijing". The Straits Times. 19 November 2018. Archived from the original on 13 April 2020. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ↑ "Olympics: Don't Promote Chinese State Propaganda". Human Rights Watch. 22 November 2021. Archived from the original on 9 December 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- ↑ Bushnell, Henry (22 November 2021). "The IOC says Peng Shuai is safe. Experts say the IOC has become a vehicle for Chinese propaganda". Yahoo! Sports. Archived from the original on 24 November 2021. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ↑ "Peng Shuai: IOC accused of 'publicity stunt' over video call". The Guardian. 22 November 2021. Archived from the original on 24 November 2021. Retrieved 25 November 2021.

- ↑ Zhai, Keith; Bachman, Rachel; Robinson, Joshua (24 November 2021). "Chinese Official Accused of Sexual Assault Played Key Role in Setting Up Beijing 2022 Olympics". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 25 November 2021. Retrieved 25 November 2021.

- ↑ Jomantas, Nicole (6 March 2020). "Handshaking Rule Suspended at USA Fencing Events". USA Fencing.

- ↑ Hopkins, Amanda (12 March 2020). "Oceania U20s and Handshaking Rule". Fencing New Zealand.

- ↑ "Handshaking Rule Temporarily Suspended". British Fencing. 5 March 2020.

- ↑ "FIE OUTLINE of RISK-MITIGATION REQUIREMENTS for NATIONAL FENCING FEDERATIONS and COMPETITION ORGANIZERS in the CONTEXT of COVID-19; PREPARED by FIE TASK FORCE and REVIEWED by FIE MEDICAL COMMISSION and FIE LEGAL COMMISSION," FIE, 1 July 2020 and September 2020.

- ↑ "FIE OUTLINE of RISK-MITIGATION REQUIREMENTS for NATIONAL FENCING FEDERATIONS and COMPETITION ORGANISERS in the CONTEXT of COVID-19 (FORMIR – COVID-19) PREPARED by FIE TASK FORCE and REVIEWED by FIE MEDICAL COMMISSION and FIE LEGAL COMMISSION," FIE, January 2021.]

- ↑ "World Fencing Championships: Ukraine's Olga Kharlan disqualified for refusing Russian Anna Smirnov's handshake". BBC. 27 July 2023.

- ↑ Aadi Nair (27 July 2023). "Ukrainian fencer disqualified from world championships for refusing handshake with Russian opponent; Olga Kharlan offered to touch blades after beating Anna Smirnova, who then staged a sit-down protest at the handshake refusal". The Independent.

- ↑ "Ukrainian fencer won't shake hands with Russian at world championships, gets Olympic spot". USA TODAY.

- ↑ Yevhen Kizilov (28 July 2023). "Ukrainian fencer gets automatically qualified for Olympics". Ukrainska Pravda. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

"Russia-Ukraine conflict: Fencer Olga Kharlan ban lifted as she is handed Olympic spot". BBC Sport. 28 July 2023. Retrieved 28 July 2023. - ↑ "Ukraine's Kharlan assured of Paris 2024 place by IOC after handshake furore". Inside the Games. 28 July 2023.

- ↑ IOC Executive Board suspends Russian Olympic Committee with immediate effect

Further reading

- Buchanon, Ian; Mallon, Bill (2006). Historical Dictionary of the Olympic Movement. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-5574-8.

- Chappelet, Jean-Loup; Brenda Kübler-Mabbott (2008). International Olympic Committee and the Olympic system: the governance of world sport. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-43167-5.

- Cooper-Chen, Anne (2005). Global entertainment media. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 978-0-8058-5168-7. Retrieved 21 March 2009.

- Lenskyj, Helen Jefferson (2000). Inside the Olympic Industry: Power, Politics and Activism. New York: SUNY.

- Podnieks, Andrew; Szemberg, Szymon (2008). IIHF Top 100 Hockey Stories of All-Time. H. B. Fenn & Company, Ltd. ISBN 978-1-55168-358-4. Archived from the original on 21 March 2009. Retrieved 25 March 2009.