Immunosuppressive drugs, also known as immunosuppressive agents, immunosuppressants and antirejection medications, are drugs that inhibit or prevent the activity of the immune system.

Classification

Immunosuppressive drugs can be classified into five groups:

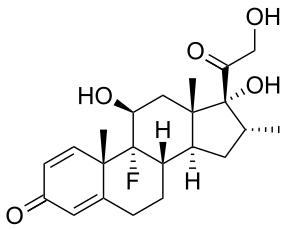

Glucocorticoids

In pharmacologic (supraphysiologic) doses, glucocorticoids, such as prednisone, dexamethasone, and hydrocortisone are used to suppress various allergic, inflammatory, and autoimmune disorders. They are also administered as posttransplantory immunosuppressants to prevent the acute transplant rejection and graft-versus-host disease. Nevertheless, they do not prevent an infection and also inhibit later reparative processes.

Immunosuppressive mechanism

Glucocorticoids suppress cell-mediated immunity. They act by inhibiting gene expression of cytokines including Interleukin 1 (IL-1), IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-alpha by binding to corticosteroid response elements on DNA.[1] This decrease in cytokine production reduces T cell proliferation. With decreased T cell proliferation there is decreased production of IL-2. This further decreases the proliferation of T cells.[2][3]

Glucocorticoids also suppress the humoral immunity, causing B cells to express smaller amounts of IL-2 and IL-2 receptors. This diminishes both B cell clone expansion and antibody synthesis.

Anti-inflammatory effects

Glucocorticoids influence all types of inflammatory events, no matter their cause. They induce the lipocortin-1 (annexin-1) synthesis, which then binds to cell membranes preventing the phospholipase A2 from coming into contact with its substrate arachidonic acid. This leads to diminished eicosanoid production. The cyclooxygenase (both COX-1 and COX-2) expression is also suppressed, potentiating the effect.

Glucocorticoids also stimulate the lipocortin-1 escaping to the extracellular space, where it binds to the leukocyte membrane receptors and inhibits various inflammatory events: epithelial adhesion, emigration, chemotaxis, phagocytosis, respiratory burst, and the release of various inflammatory mediators (lysosomal enzymes, cytokines, tissue plasminogen activator, chemokines, etc.) from neutrophils, macrophages, and mastocytes.

Cytostatics

Cytostatics inhibit cell division. In immunotherapy, they are used in smaller doses than in the treatment of malignant diseases. They affect the proliferation of both T cells and B cells. Due to their highest effectiveness, purine analogs are most frequently administered.

Alkylating agents

The alkylating agents used in immunotherapy are nitrogen mustards (cyclophosphamide), nitrosoureas, platinum compounds, and others. Cyclophosphamide (Baxter's Cytoxan) is probably the most potent immunosuppressive compound. In small doses, it is very efficient in the therapy of systemic lupus erythematosus, autoimmune hemolytic anemias, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, and other immune diseases. High doses cause pancytopenia and hemorrhagic cystitis.

Antimetabolites

Antimetabolites interfere with the synthesis of nucleic acids. These include:

- folic acid analogues, such as methotrexate

- purine analogues, such as azathioprine and mercaptopurine

- pyrimidine analogues, such as fluorouracil

- protein synthesis inhibitors.

Methotrexate

Methotrexate is a folic acid analogue. It binds dihydrofolate reductase and prevents synthesis of tetrahydrofolate. It is used in the treatment of autoimmune diseases (for example rheumatoid arthritis or Behcet's Disease) and in transplantations.

Azathioprine and mercaptopurine

Azathioprine (Prometheus' Imuran), is the main immunosuppressive cytotoxic substance. It is extensively used to control transplant rejection reactions. It is nonenzymatically cleaved to mercaptopurine, that acts as a purine analogue and an inhibitor of DNA synthesis. Mercaptopurine itself can also be administered directly.

By preventing the clonal expansion of lymphocytes in the induction phase of the immune response, it affects both the cell and the humoral immunity. It is also efficient in the treatment of autoimmune diseases.

Cytotoxic antibiotics

Among these, dactinomycin is the most important. It is used in kidney transplantations. Other cytotoxic antibiotics are anthracyclines, mitomycin C, bleomycin, mithramycin.

Antibodies

Antibodies are sometimes used as a quick and potent immunosuppressive therapy to prevent the acute rejection reactions as well as a targeted treatment of lymphoproliferative or autoimmune disorders (e.g., anti-CD20 monoclonals).

Polyclonal antibodies

Heterologous polyclonal antibodies are obtained from the serum of animals (e.g., rabbit, horse), and injected with the patient's thymocytes or lymphocytes. The antilymphocyte (ALG) and antithymocyte antigens (ATG) are being used. They are part of the steroid-resistant acute rejection reaction and grave aplastic anemia treatment. However, they are added primarily to other immunosuppressives to diminish their dosage and toxicity. They also allow transition to cyclosporin therapy.

Polyclonal antibodies inhibit T lymphocytes and cause their lysis, which is both complement-mediated cytolysis and cell-mediated opsonization followed by removal of reticuloendothelial cells from the circulation in the spleen and liver. In this way, polyclonal antibodies inhibit cell-mediated immune reactions, including graft rejection, delayed hypersensitivity (i.e., tuberculin skin reaction), and the graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), but influence thymus-dependent antibody production.

As of March 2005, there are two preparations available to the market: Atgam, obtained from horse serum, and Thymoglobuline, obtained from rabbit serum. Polyclonal antibodies affect all lymphocytes and cause general immunosuppression, possibly leading to post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders (PTLD) or serious infections, especially by cytomegalovirus. To reduce these risks, treatment is provided in a hospital, where adequate isolation from infection is available. They are usually administered for five days intravenously in the appropriate quantity. Patients stay in the hospital as long as three weeks to give the immune system time to recover to a point where there is no longer a risk of serum sickness.

Because of a high immunogenicity of polyclonal antibodies, almost all patients have an acute reaction to the treatment. It is characterized by fever, rigor episodes, and even anaphylaxis. Later during the treatment, some patients develop serum sickness or immune complex glomerulonephritis. Serum sickness arises seven to fourteen days after the therapy has begun. The patient has fever, joint pain, and erythema that can be soothed with the use of steroids and analgesics. Urticaria (hives) can also be present. It is possible to diminish their toxicity by using highly purified serum fractions and intravenous administration in the combination with other immunosuppressants, for example, calcineurin inhibitors, cytostatics, and corticosteroids. The most frequent combination is to use antibodies and ciclosporin simultaneously in order to prevent patients from gradually developing a strong immune response to these drugs, reducing or eliminating their effectiveness.

Monoclonal antibodies

Monoclonal antibodies are directed towards exactly defined antigens. Therefore, they cause fewer side-effects. Especially significant are the IL-2 receptor- (CD25-) and CD3-directed antibodies. They are used to prevent the rejection of transplanted organs, but also to track changes in the lymphocyte subpopulations. It is reasonable to expect similar new drugs in the future.

T-cell receptor directed antibodies

Muromonab-CD3 is a murine anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody of the IgG2a type that was previously used to prevent T-cell activation and proliferation by binding the T-cell receptor complex present on all differentiated T cells. As such it was one of the first potent immunosuppressive substances and was administered to control the steroid- and/or polyclonal antibodies-resistant acute rejection episodes. As it acts more specifically than polyclonal antibodies it was also used prophylactically in transplantations. However, muromonab-CD3 is no longer produced,[4] and this mouse monoclonal antibody has been replaced in the clinic with chimeric, humanized, or human monoclonal antibodies.

The muromonab's mechanism of action is only partially understood. It is known that the molecule binds TCR/CD3 receptor complex. In the first few administrations this binding non-specifically activates T-cells, leading to a serious syndrome 30 to 60 minutes later. It is characterized by fever, myalgia, headache, and arthralgia. Sometimes it develops in a life-threatening reaction of the cardiovascular system and the central nervous system, requiring a lengthy therapy. Past this period CD3 blocks the TCR-antigen binding and causes conformational change or the removal of the entire TCR3/CD3 complex from the T-cell surface. This lowers the number of available T-cells, perhaps by sensitizing them for the uptake by the epithelial reticular cells. The cross-binding of CD3 molecules as well activates an intracellular signal causing the T cell anergy or apoptosis, unless the cells receive another signal through a co-stimulatory molecule. CD3 antibodies shift the balance from Th1 to Th2 cells as CD3 stimulates Th1 activation.[5]

The patient may develop neutralizing antibodies reducing the effectiveness of muromonab-CD3. Muromonab-CD3 can cause excessive immunosuppression. Although CD3 antibodies act more specifically than polyclonal antibodies, they lower the cell-mediated immunity significantly, predisposing the patient to opportunistic infections and malignancies.[6]

IL-2 receptor directed antibodies

Interleukin-2 is an important immune system regulator necessary for the clone expansion and survival of activated lymphocytes T. Its effects are mediated by the trimer cell surface receptor IL-2a, consisting of the α, β, and γ chains. The IL-2a (CD25, T-cell activation antigen, TAC) is expressed only by the already-activated T lymphocytes. Therefore, it is of special significance to the selective immunosuppressive treatment, and research has been focused on the development of effective and safe anti-IL-2 antibodies. By the use of recombinant gene technology, the mouse anti-Tac antibodies have been modified, leading to the presentation of two chimeric mouse/human anti-Tac antibodies in the year 1998: basiliximab (Simulect) and daclizumab (Zenapax). These drugs act by binding the IL-2a receptor's α chain, preventing the IL-2 induced clonal expansion of activated lymphocytes and shortening their survival. They are used in the prophylaxis of the acute organ rejection after bilateral kidney transplantation, both being similarly effective and with only few side-effects.

Drugs acting on immunophilins

Ciclosporin

Like tacrolimus, ciclosporin (Novartis' Sandimmune) is a calcineurin inhibitor (CNI). It has been in use since 1983 and is one of the most widely used immunosuppressive drugs. It is a cyclic fungal peptide, composed of 11 amino acids.

Ciclosporin is thought to bind to the cytosolic protein cyclophilin (an immunophilin) of immunocompetent lymphocytes, especially T-lymphocytes. This complex of ciclosporin and cyclophilin inhibits the phosphatase calcineurin, which under normal circumstances induces the transcription of interleukin-2. The drug also inhibits lymphokine production and interleukin release, leading to a reduced function of effector T-cells.

Ciclosporin is used in the treatment of acute rejection reactions, but has been increasingly substituted with newer, and less nephrotoxic,[7] immunosuppressants.

Calcineurin inhibitors and azathioprine have been linked with post-transplant malignancies and skin cancers in organ transplant recipients. Non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC) after kidney transplantation is common and can result in significant morbidity and mortality. The results of several studies suggest that calcineurin inhibitors have oncogenic properties mainly linked to the production of cytokines that promote tumor growth, metastasis and angiogenesis.

This drug has been reported to reduce the frequency of regulatory T cells (T-Reg) and after converting from a CNI monotherapy to a mycophenolate monotherapy, patients were found to have increased graft success and T-Reg frequency.[8]

Tacrolimus

Tacrolimus (trade names Prograf, Astagraf XL, Envarsus XR) is a product of the bacterium Streptomyces tsukubensis. It is a macrolide lactone and acts by inhibiting calcineurin.

The drug is used primarily in liver and kidney transplantations, although in some clinics it is used in heart, lung, and heart/lung transplantations. It binds to the immunophilin FKBP1A, followed by the binding of the complex to calcineurin and the inhibition of its phosphatase activity. In this way, it prevents the cell from transitioning from the G0 into G1 phase of the cell cycle. Tacrolimus is more potent than ciclosporin and has less pronounced side-effects.

Sirolimus

Sirolimus (rapamycin, trade name Rapamune) is a macrolide lactone, produced by the actinomycete bacterium Streptomyces hygroscopicus. It is used to prevent rejection reactions. Although it is a structural analogue of tacrolimus, it acts somewhat differently and has different side-effects.

Contrary to ciclosporin and tacrolimus, drugs that affect the first phase of T lymphocyte activation, sirolimus affects the second phase, namely signal transduction and lymphocyte clonal proliferation. It binds to FKBP1A like tacrolimus, however the complex does not inhibit calcineurin but another protein, mTOR. Therefore, sirolimus acts synergistically with ciclosporin and, in combination with other immunosuppressants, has few side effects. Also, it indirectly inhibits several T lymphocyte-specific kinases and phosphatases, hence preventing their transition from G1 to S phase of the cell cycle. In a similar manner, Sirolimus prevents B cell differentiation into plasma cells, reducing production of IgM, IgG, and IgA antibodies.

It is also active against tumors that are PI3K/AKT/mTOR-dependent.

Everolimus

Everolimus is an analog of sirolimus and also is an mTOR inhibitor.

Zotarolimus

Zotarolimus is a semi-synthetic derivative of sirolimus used in drug-eluting stents.

Other drugs

Interferons

IFN-β suppresses the production of Th1 cytokines and the activation of monocytes. It is used to slow down the progression of multiple sclerosis. IFN-γ is able to trigger lymphocytic apoptosis.

Opioids

Prolonged use of opioids may cause immunosuppression of both innate and adaptive immunity.[9] Decrease in proliferation as well as immune function has been observed in macrophages, as well as lymphocytes. It is thought that these effects are mediated by opioid receptors expressed on the surface of these immune cells.[9]

TNF binding proteins

A TNF-α (tumor necrosis factor-alpha) binding protein is a monoclonal antibody or a circulating receptor such as infliximab (Remicade), etanercept (Enbrel), or adalimumab (Humira) that binds to TNF-α, preventing it from inducing the synthesis of IL-1 and IL-6 and the adhesion of lymphocyte-activating molecules. They are used in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, Crohn's disease, and psoriasis.

These drugs may raise the risk of contracting tuberculosis or inducing a latent infection to become active. Infliximab and adalimumab have label warnings stating that patients should be evaluated for latent TB infection and treatment should be initiated prior to starting therapy with them.

TNF or the effects of TNF are also suppressed by various natural compounds, including curcumin (an ingredient in turmeric) and catechins (in green tea).

Mycophenolate

Mycophenolic acid acts as a non-competitive, selective, and reversible inhibitor of inosine-5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase (IMPDH), which is a key enzyme in the de novo guanosine nucleotide synthesis. In contrast to other human cell types, lymphocytes B and T are very dependent on this process. Mycophenolate mofetil is used in combination with ciclosporin or tacrolimus in transplant patients.

Small biological agents

Fingolimod is a synthetic immunosuppressant. It increases the expression or changes the function of certain adhesion molecules (α4/β7 integrin) in lymphocytes, so they accumulate in the lymphatic tissue (lymphatic nodes) and their number in the circulation is diminished. In this respect, it differs from all other known immunosuppressants.

Myriocin has been reported being 10 to 100 times more potent than Ciclosporin.

Therapy

Immunosuppressive drugs are used in immunosuppressive therapy to:

- Prevent the rejection of transplanted organs and tissues (e.g., bone marrow, heart, kidney, liver)

- Treat autoimmune diseases or diseases that are most likely of autoimmune origin (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, myasthenia gravis, psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, vitiligo, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, systemic sclerosis, scleroderma, sarcoidosis, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, Crohn's disease, Behcet's Disease, pemphigus, ankylosing spondylitis, and ulcerative colitis).

- Treat some other non-autoimmune inflammatory diseases (e.g., long term allergic asthma control).

Side effects

A common side-effect of many immunosuppressive drugs is immunodeficiency, because the majority of them act non-selectively, resulting in increased susceptibility to infections, decreased cancer immunosurveillance and decreased ability to produce antibodies after vaccination.[10][11] However, the vaccination status of patients taking immunosuppressive drugs for chronic diseases such as Rheumatoid arthritis or Inflammatory bowel disease should be investigated before starting any treatment, and patients should eventually be vaccinated against Vaccine-preventable disease.[12] Some studies showed a low vaccination rate against some Vaccine-preventable disease among patients taking immunosuppressive drugs, despite a generally positive attitude towards vaccinations.[13]

There are also other side-effects, such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, hyperglycemia, peptic ulcers, lipodystrophy, moon face, liver and kidney injury. The immunosuppressive drugs also interact with other medicines and affect their metabolism and action. Actual or suspected immunosuppressive agents can be evaluated in terms of their effects on lymphocyte subpopulations in tissues using immunohistochemistry.[14]

See also

References

- ↑ Jennings DL (2020). DiPiro JT, Yee GC, Posey LM, Haines ST, Nolin TD, Ellingrod VL (eds.). Pharmacotherapy : A Pathophysiologic Approach (11th ed.). United States of America: McGraw Hill Medical. ISBN 978-1-260-11681-6. OCLC 1142934194.

- ↑ Coutinho AE, Chapman KE (March 2011). "The anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects of glucocorticoids, recent developments and mechanistic insights". Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 335 (1): 2–13. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2010.04.005. PMC 3047790. PMID 20398732.

- ↑ Schimmer BP, Funder JW (2018). Shanahan JF, Lebowitz H (eds.). Goodman & Gilman's the pharmacological basis of therapeutics (13th ed.). New York: McGraw Hill Medical. ISBN 978-1-259-58473-2. OCLC 993810322.

- ↑ Reichert JM (May 2012). "Marketed therapeutic antibodies compendium". mAbs. 4 (3): 413–415. doi:10.4161/mabs.19931. PMC 3355480. PMID 22531442.

- ↑ Smeets RL, Fleuren WW, He X, Vink PM, Wijnands F, Gorecka M, et al. (March 2012). "Molecular pathway profiling of T lymphocyte signal transduction pathways; Th1 and Th2 genomic fingerprints are defined by TCR and CD28-mediated signaling". BMC Immunology. 13 (1): 12. doi:10.1186/1471-2172-13-12. PMC 3355027. PMID 22413885.

- ↑ Yang H, Parkhouse RM, Wileman T (June 2005). "Monoclonal antibodies that identify the CD3 molecules expressed specifically at the surface of porcine gammadelta-T cells". Immunology. 115 (2): 189–196. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02137.x. PMC 1782146. PMID 15885124.

- ↑ Naesens M, Kuypers DR, Sarwal M (February 2009). "Calcineurin inhibitor nephrotoxicity". Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 4 (2): 481–508. doi:10.2215/CJN.04800908. PMID 19218475.

- ↑ Demirkiran A, Sewgobind VD, van der Weijde J, Kok A, Baan CC, Kwekkeboom J, et al. (April 2009). "Conversion from calcineurin inhibitor to mycophenolate mofetil-based immunosuppression changes the frequency and phenotype of CD4+FOXP3+ regulatory T cells". Transplantation. 87 (7): 1062–1068. doi:10.1097/tp.0b013e31819d2032. PMID 19352129. S2CID 23118360.

- 1 2 Roy S, Loh HH (November 1996). "Effects of opioids on the immune system". Neurochemical Research. 21 (11): 1375–1386. doi:10.1007/BF02532379. PMID 8947928. S2CID 7652574.

- ↑ Lee AR, Wong SY, Chai LY, Lee SC, Lee MX, Muthiah MD, et al. (March 2022). "Efficacy of covid-19 vaccines in immunocompromised patients: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ. 376: e068632. doi:10.1136/bmj-2021-068632. PMC 8889026. PMID 35236664.

- ↑ Zbinden D, Manuel O (February 2014). "Influenza vaccination in immunocompromised patients: efficacy and safety". Immunotherapy. 6 (2): 131–139. doi:10.2217/imt.13.171. PMID 24491087.

- ↑ Kucharzik T., Ellul P., Greuter T., Rahier J.F., Verstockt B., Abreu C., Albuquerque A., Allocca M., Esteve M., Farraye F.A., et al. ECCO Guidelines on the Prevention, Diagnosis, and Management of Infections in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Crohn’s Colitis. 2021;15:879–913. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab052.

- ↑ Costantino A, Michelon M, Noviello D, Macaluso FS, Leone S, Bonaccorso N, Costantino C, Vecchi M, Caprioli F; AMICI Scientific Board. Attitudes towards Vaccinations in a National Italian Cohort of Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Vaccines (Basel). 2023 Oct 13;11(10):1591. doi: 10.3390/vaccines11101591. PMID 37896993; PMCID: PMC10611209.

- ↑ Gillett NA, Chan C (April 2000). "Applications of immunohistochemistry in the evaluation of immunosuppressive agents". Human & Experimental Toxicology. 19 (4): 251–254. Bibcode:2000HETox..19..251G. doi:10.1191/096032700678815819. PMID 10918517. S2CID 31374180.

Further reading

- Gummert JF, Ikonen T, Morris RE (June 1999). "Newer immunosuppressive drugs: a review". Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 10 (6): 1366–1380. doi:10.1681/ASN.V1061366. PMID 10361877.

- Armstrong VW (February 2002). "Principles and Practice of Monitoring Immunosuppressive Drugs". LaboratoriumsMedizin. 26 (1–2): 27–36. doi:10.1515/LabMed.2002.005. S2CID 79514959.

External links

- "Pancreas-Kidney Transplantation: Drugs". pancreas-kidney.com. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. a brief history of immunosuppressive drugs. Accessed on 21 August 2005.

- Papich M (2001). "Immunosuppressive drug therapy". World Small Animal Veterinary Association (WSAVA). Archived from the original on 30 November 2016. Retrieved 21 August 2005.

- "Are Immunosuppressive Drugs a Useful Adjuvant to Treatment of HIV with Antiretrovirals?". Hivandhepatitis.com. Archived from the original on 28 February 2019. Retrieved 21 August 2005.

- Induction of Tolerance at eMedicine

- "Immunosuppressants". A to Z Health Guide. National Kidney Foundation. 24 December 2015.

- "Immunosuppressants, Pharmacologic profile". Drugguide.com. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- Immunosuppressive+Agents at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)