| Hiranyaksha | |

|---|---|

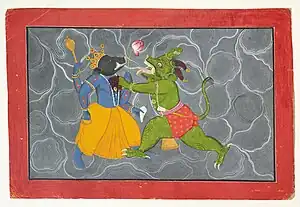

Varaha battles the Hiranyaksha, Scene from the Bhagavata Purana by Manaku of Guler (c. 1740) | |

| Affiliation | Asura |

| Abode | Patala |

| Weapon | Mace |

| Personal information | |

| Parents | Kashyapa and Diti |

| Siblings | Hiranyakashipu (elder brother) Holika (younger sister) |

| Consort | Rushabhanu [1] |

| Children | Andhaka Narkasur |

Hiranyaksha (Sanskrit: हिरण्याक्ष, romanized: Hiraṇyākṣa, lit. 'golden-eyed'), also known as Hiranyanetra (Sanskrit: हिरण्यनेत्र)[2] is an asura in Hindu mythology. He is described to have submerged the earth and terrorised the three worlds. He is slain by the Varaha (wild boar) avatar of Vishnu, who rescued the earth goddess Bhumi and restored order to the earth.[3][4]

Legend

Some of the Puranas present Hiranyaksha as the son of Diti and Kashyapa.[5] Having performed austerities to propitiate Brahma, Hiranyaksha received the boon of invulnerability of meeting his death by neither any god, man, nor beast.[6][7]

Having received this boon, Hiranyaksha assaulted the defenceless Bhumi and pulled her deep beneath the cosmic ocean. The other deities appealed to Vishnu to save the earth goddess and creation. Answering their plea, Vishnu assumed the avatar of a wild boar (Varaha) to rescue the goddess. Hiranyaksha attempted to obstruct him, after which he was slain by Vishnu.[5][8]

Hiranyaksha had an elder brother named Hiranyakashipu, who similarly achieved a boon of invulnerability and conquered the three worlds, seeking vengeance for his brother's death.[9] He tried to persecute and abuse his son Prahlada for being a faithful devotee of Vishnu. While Hiranyaksha was slain by Varaha (the boar avatar of Vishnu), Hiranyakashipu was killed by Narasimha (the man-lion avatar of Vishnu).[5] Their younger sister was Holika, who tried to kill her nephew by attempting to immolate him but got burnt herself and killed.

In some texts including the Bhagavata Purana, Hiranyaksha is an incarnation of one of the dvarapalas (gatekeepers) of Vishnu named Vijaya. Vishnu's guardians Jaya-Vijaya, were cursed by the Four Kumaras (Brahma's sons) to incarnate on earth either three times as enemies of Vishnu, or seven times as his devotees. They chose to take birth on earth thrice. During their first births (during the Satya Yuga), they were born as Hiranyakashipu and Hiranyaksha. During their second births, (during the Treta Yuga), they were born as Ravana and Kumbhakarna. During their third births (during the Dvapara Yuga), they were born as Shishupala and Dantavakra.

Origins and significance

This Hindu legend has roots in the Vedic literature such as Taittariya Samhita and Shatapatha Brahmana, and is found in many post-Vedic texts.[10][11] These legends depict the earth goddess (Bhumi or Prithvi) in an existential crisis, where neither she nor the life she supports can survive. She is drowning and overwhelmed in the cosmic ocean. Vishnu emerges in the form of a man-boar avatar. He, as the protagonist of the legend, descends into the ocean and finds her. She hangs onto his tusk, and he lifts her out to safety. Good wins, the crisis ends, and Vishnu once again fulfills his cosmic duty. The Varaha legend has been one of many archetypal legends in the Hindu text embedded with the theme of right versus wrong, good versus evil symbolism, and of someone willing to go to the depths and do what is necessary to rescue the righteous and uphold dharma.[10][11][12]

See also

References

- ↑ "Hiraṇyakaśipu consoles his mother and kinsmen [Chapter 2]". 30 August 2022.

- ↑ George M. Williams (27 March 2008). Handbook of Hindu Mythology. Oxford University Press. pp. 54–. ISBN 978-0-19-533261-2. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- ↑ Williams, George M. (27 March 2008). Handbook of Hindu Mythology. OUP USA. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-19-533261-2.

- ↑ Jones, Constance; Ryan, James D. (2006). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Infobase Publishing. p. 189. ISBN 978-0-8160-7564-5.

- 1 2 3 Roshen Dalal (2010). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-14-341421-6.

- ↑ Cole, W. Owen (1 June 1996). Six World Faiths. A&C Black. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-4411-5928-1.

- ↑ Phillips, Charles; Kerrigan, Michael; Gould, David (15 December 2011). Ancient India's Myths and Beliefs. The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-4488-5990-0.

- ↑ George M. Williams (2008). Handbook of Hindu Mythology. Oxford University Press. pp. 154–155, 223–224. ISBN 978-0-19-533261-2.

- ↑ Hudson, D. Dennis (25 September 2008). The Body of God: An Emperor's Palace for Krishna in Eighth-Century Kanchipuram. Oxford University Press. p. 202. ISBN 978-0-19-045140-0.

- 1 2 H. von Stietencron (1986). Th. P. van Baaren; A Schimmel; et al. (eds.). Approaches to Iconology. Brill Academic. pp. 16–22 with footnotes. ISBN 90-04-07772-3.

- 1 2 Debala Mitra, ’Varāha Cave at Udayagiri – An Iconographic Study’, Journal of the Asiatic Society 5 (1963): 99-103; J. C. Harle, Gupta Sculpture (Oxford, 1974): figures 8-17.

- ↑ Joanna Gottfried Williams (1982). The Art of Gupta India: Empire and Province. Princeton University Press. pp. 42–46. ISBN 978-0-691-10126-2.

- Dictionary of Hindu Lore and Legend (ISBN 0-500-51088-1) by Anna Dhallapiccola