Herbert Mullin | |

|---|---|

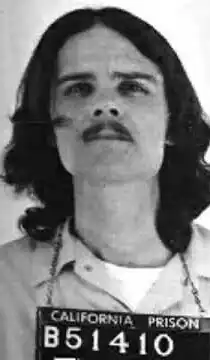

Mullin c. 1973 | |

| Born | Herbert William Mullin April 18, 1947 Salinas, California, U.S. |

| Died | August 18, 2022 (aged 75) |

| Height | 5 ft 9 in (175 cm) |

| Conviction(s) | Murder |

| Criminal penalty | Life imprisonment |

| Details | |

| Victims | 13 |

Span of crimes | October 13, 1972 – February 13, 1973 |

| Country | United States |

| State(s) | California |

Date apprehended | February 13, 1973 |

| Imprisoned at | California Health Care Facility |

| Website | herbertwilliammullin |

Herbert William Mullin (April 18, 1947[1] – August 18, 2022)[2] was an American serial killer who killed 13 people in California in the early 1970s. He confessed to the killings, which he claimed prevented earthquakes. In 1973, after a trial to determine whether he was legally insane or culpable, he was convicted of two murders in the first-degree and nine in the second-degree, and sentenced to life imprisonment. During his imprisonment, he was denied parole eight times.[3][4]

Mullin and Edmund Kemper overlapped in their 1972 to 1973 murder sprees, adding confusion to the police investigations and ending with both being arrested, within a few weeks of each other, after the deaths of 21 people.[5]

Early life, education, and mental health issues

Herbert William Mullin was born on April 18, 1947, in Salinas, California.[6] His father was reportedly stern but not abusive.[7] Not long before Mullin's fifth birthday, the family moved to San Francisco.[8]

Mullin had numerous friends at school and was voted "Most Likely to Succeed" when he was 16 by his classmates at San Lorenzo Valley High School, yet he also experienced difficulties at this time, largely due to paranoid schizophrenic disorder.[9] Shortly after they graduated from San Lorenzo Valley High School in 1965, one of Mullin's friends, Dean Richardson, was killed in a car accident, devastating Mullin. He built "shrines" to Richardson in his room and became obsessed with the idea of reincarnation.[10]

In 1969, Mullin was admitted to Mendocino State Hospital.[11] Over the next few years, he entered various mental hospitals, but was discharged after spells as being no harm to himself or others.[9] In total, he was committed to five mental hospitals.[12] By the time he was in his mid-twenties, he had a diagnosis of paranoid schizophrenia, accelerated by his usage of LSD and cannabis.[9]

Murders

By 1972, Mullin was 25 and had moved back in with his parents in Felton, California, in the Santa Cruz Mountains.[4] His birthday, April 18, was the anniversary of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, which he thought was very significant.[13]

Mullin believed that the Vietnam War had produced enough American deaths to forestall earthquakes as a blood sacrifice to nature, but that with the war winding down by late 1972 (from an American perspective) he would need to start killing people in order to have enough deaths to keep a calamitous earthquake away. It was for this reason, he later said, that his father, through telepathy, had ordered him to take lives.[14]

On October 13, 1972, Mullin beat 55-year-old vagrant Lawrence "Whitey" White's head with a baseball bat when the transient looked at the engine of his 1958 Chevy station wagon after Mullin had pretended to have car trouble and pulled over, opening the hood.[15][16] White had offered to help fix his car in exchange for a ride. Mullin dragged White's body into the woods, where it was found the next day.[16] He later claimed his victim looked like Jonah from the Bible, and sent him telepathic messages "Hey, man, pick me up and throw me over the boat. Kill me so that others will be saved."[15]

Mullin soon set out to commit a second murder with the intent to both test his hypothesis that the environment was being rapidly polluted and to follow a command hallucination of his father's voice directing him to make another sacrifice.[16] On October 24, 1972, Mullin encountered Mary Margaret Guilfoyle, a student from Cabrillo College who was running late for an appointment.[17] He offered Guilfoyle a lift and stabbed her in the chest while driving.[18] He later disemboweled Guilfoyle's corpse to examine her organs for evidence supporting his ideas on pollution.[17] Guilfoyle's body was located in February 1973, several months after her murder.[16]

Shortly thereafter, Mullin began having doubts about the hallucinatory instructions he believed were from his father. This uncertainty led Mullin to attend St. Mary's Catholic Church in Los Gatos on November 2, 1972, with the aim of confessing.[19][20] While in custody in 1973, Mullin alleged that the priest he spoke to in the confessional, Father Henri Tomei, volunteered to be his next sacrifice,[19][21] which led Mullin to hit, kick, and stab Tomei to death on the spot before fleeing.[19]

Around January 1973, Mullin applied to join the United States Marine Corps in an attempt to legally conduct what he perceived as his mission but was barred from entry when he refused to sign his criminal record.[13]

By the start of 1973, Mullin had stopped taking drugs completely and began blaming the faults in his life on his previous substance use.[19] He decided to locate Jim Gianera,[22] his former friend from high school who first introduced him to cannabis, and whom Mullin subsequently perceived as the originator of Mullin's eventual heavy drug use.[19][23] In early January 1973, Mullin drove to a remote area of Santa Cruz where he recalled Gianera to live. The resident of the first house Mullin approached was a woman named Kathleen "Kathy" Francis, a close friend of Jim Gianera and his wife Joan; Francis directed Mullin to Gianera's actual inhabitance (a cabin further down the same road).[24][25] Mullin proceeded to Gianera's home, where he demanded to know why Gianera offered him the early taste of cannabis that Mullin alleged ruined his life. Mullin decided that the former friend's answer was unsatisfactory and shot him.[26] Dying, the man crawled to his bathroom in an attempt to tell his wife to lock the bathroom door, but Mullin broke down the door and fatally shot her too.[26] Mullin then returned to the home of Kathy Francis and shot her and her two children, 4-year-old Daemon Francis and 9-year-old David Hughes, to death, then stabbed each victim multiple times after death. The police thought that the deaths in both homes were drug-related and did not suspect they were in any way connected with the priest's death or the previous murders of hitchhikers.[26]

About a month later, on February 10, 1973, Mullin was hiking in the state park in Santa Cruz[27] where he encountered four teenage boys (Robert Spector, aged 18, Brian Scott Card, 19, David Oliker, 18, and Mark Dreibelbis, 15) camping illegally.[28][29] He walked over to them, engaged them in a brief conversation and claimed to be a park ranger.[26] He told them to leave because they were, according to Mullin, "polluting" the forest. However, they shooed him away and stayed in the tent. The next day, Mullin returned and shot all four of them in the head with his .22 caliber pistol, killing them.[26][28] When he had finished, he took their .22 caliber rifle and 20 dollars.[30]

The next killing happened before the bodies of Mullin's previous victims were found later that week.[26][30] It occurred as Mullin was driving firewood in his station wagon.[26] He noticed his victim, a 72-year-old retired prizefighter and fishmonger named Fred Abbie Perez,[31] working in his garden in Santa Cruz.[25] Mullin did a U-turn, came back down the street, stopped, put the rifle across the hood of his car, and shot Perez once in the heart.[4] He committed this killing in full sight of the dead man's neighbor, who got Mullin's license plate.[26] A few minutes after the description was broadcast on the police radio, a "docile" Mullin was ordered to pull over and was arrested by a patrolman. In his car was the .22 caliber pistol used to kill the people in the cabins. He did not attempt to use the recently fired .22 caliber rifle on the seat next to him.[32]

The police failed to recognize a pattern at the time of Mullin's murders due to several factors: firstly, the murders did not appear to be connected by a similar weapon or modus operandi; secondly, the victims differed from each other in terms of age, race, and sex; and finally, Edmund Kemper, who would kill the last of his own eight victims just a few weeks later, was operating in approximately the same area at the same time.[16]

Mullin had committed his murder spree over four months.[33]

Trial and imprisonment

The Santa Cruz County District Attorney's office charged Mullin with ten murders, and Mullin's trial opened on July 30, 1973.[34] Mullin had admitted to all the crimes; therefore, the trial focused on whether he was legally sane (which, under U.S. law, means that he understood the nature and quality of his actions, and understood right from wrong).[35] The fact that he had covered his tracks and shown premeditation in some of his crimes was highlighted by prosecutor Chris Cottle [36] while the defense (public defender Jim Jackson) argued that Mullin's delusions made him kill.[37] On August 19, 1973, after fourteen hours of deliberation, Mullin was found guilty of first-degree murder in the killings of Jim Gianera and Kathy Francis – because they were deemed premeditated– and eight counts of second degree murder in the other killings– because they were considered "impulse" by the jury.[38][39] Mullin was convicted of the ten murders at the age of 26.[40]

The Santa Clara County District Attorney's office charged Mullin for the murder of Henri Tomei. On December 11, 1973, the day his trial was to begin, he pled guilty to second-degree murder after originally pleading not guilty by reason of insanity to first-degree murder. He was sentenced to life imprisonment in the Santa Cruz County trial and was denied parole eight times from 1980 on. He was incarcerated at Mule Creek State Prison, in Ione, California.[3]

While in custody, Mullin said he committed his crimes only in an attempt to save the environment.[33] He was diagnosed by Dr. David Marlowe from the University of California at Santa Cruz with schizophrenic reaction, paranoid type.[41]

Mullin had interactions with Edmund Kemper, another serial killer active in the same area and at the same time as he was. The two shared adjoining cells at one point. Kemper disliked Mullin, saying he killed for no good reason.[42] Kemper recalled "Well, [Mullin] had a habit of singing and bothering people when somebody tried to watch TV. So I threw water on him to shut him up. Then, when he was a good boy, I'd give him some peanuts. Herbie liked peanuts. That was effective because pretty soon he asked permission to sing. That's called behavior modification treatment."[42]

Kemper described Mullin as having a "lot of pain inside, he had a lot of anguish inside, he had a lot of hate inside, and it was addressed to people he didn't even know because he didn't dare do anything to the people he knew." In that same interview, Kemper called Mullin "a kindred spirit there" due to their similar past of being institutionalized. Kemper said he told Mullin "Herbie, I know what happened. Don't give me that bullshit about earthquakes and don't give me that crap about God was telling you. I says you couldn't even be talking to me now if God talking to you because of the pressure I'm putting on you right now, these little shocking insights into what you did, God would start talking to you right now if you were that kind of ill. Because I grew up with people like that."[43]

Death

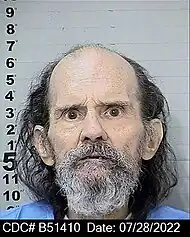

On August 18, 2022, Mullin died at age 75 from natural causes while housed at the California Health Care Facility.[44]

Victims

| Number | Name | Sex | Age | Date of Murder | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lawrence "Whitey" White | M | 55 | October 13, 1972 | Clubbed about the head repeatedly with a baseball bat |

| 2 | Mary Margaret Guilfoyle | F | 24 | October 24, 1972 | Stabbed and dissected, and deboned |

| 3 | Father Henri Tomei | M | 64 | November 2, 1972 | Beaten and stabbed through the heart |

| 4 | Jim Ralph Gianera | M | 25 | January 25, 1973 | Shot three times including in the back, puncturing his lung |

| 5 | Joan Gianera | F | 21 | January 25, 1973 | Shot in the neck and head above the left eye, then stabbed three times |

| 6 | Kathy Francis | F | 29 | January 25, 1973 | Shot, then stabbed after death |

| 7 | Daemon Francis | M | 4 | January 25, 1973 | Shot in the head, then stabbed after death |

| 8 | David Hughes | M | 9 | January 25, 1973 | Shot in the head, then stabbed after death |

| 9 | David Oliker | M | 18 | February 10, 1973 | Shot in the head |

| 10 | Robert Spector | M | 18 | February 10, 1973 | Shot in the head |

| 11 | Brian Scott Card | M | 19 | February 10, 1973 | Shot in the head |

| 12 | Mark Dreibelbis | M | 15 | February 10, 1973 | Shot in the head |

| 13 | Fred Abbie Perez | M | 72 | February 13, 1973 | Shot in the heart |

In popular culture

- Andy E. Horne played Mullin (renamed "Herbert McCormack") in the 2008 direct-to-video horror film Kemper: The CoEd Killer.

- Mullin was the subject of an episode of the television documentary series Born to Kill?.

- Mullin was mentioned twice (and was portrayed by uncredited actor Marco Aiello in a flashback) on the police procedural crime drama Criminal Minds.

- Mullin was covered on the true crime comedy podcast The Last Podcast on the Left starting with episode 416.

- Mullin was alluded to in the Church of Misery song "Megalomania" from the album Master of Brutality.

- Mullin was covered on the 57th episode of the true crime comedy podcast My Favorite Murder.

- Mullin was covered in the episode Herbert Mullin: Preventing a disaster in the True crime Podcast This is Monsters

- Mullin was covered (alongside Ed Kemper) in the first season (2021) of the Investigation Discovery podcast, Mind of a Monster.

- Mullin was featured in a comic book by Kirt Burdick titled Herbie's Song (2022)

See also

References

- ↑ Mullin, Herbert. "Herbert William Mullin, born 04/18/1947". California Birth Index. State of California. Retrieved January 31, 2022.

- ↑ "Herbert Mullin Dies of Natural Causes". California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. August 19, 2022. Retrieved August 19, 2022.

- 1 2 "California Inmate Locator". cdcr.ca.gov. Retrieved March 19, 2021.

- 1 2 3 Scott, Shirley Lynn. "Unnatural Disasters". truTV Crime Library. crimelibrary.com. Archived from the original on December 10, 2012. Retrieved March 5, 2008.

- ↑ Ressler & Shachtman 1992, p. 129

- ↑ Lunde 1979, p. 64.

- ↑ Scott, Shirley Lynn (October 21, 2012). "Herb Mullin — Normal Childhood, Abnormal Adult — Crime Library on truTV.com". Crime Library. Archived from the original on October 21, 2012. Retrieved February 2, 2022.

- ↑ Lunde 1979, p. 138.

- 1 2 3 Ressler & Shachtman 1992, p. 127.

- ↑ Scott, Shirley Lynn. "Unnatural Disasters". TruTV. Archived from the original on October 21, 2012. Retrieved September 27, 2012.

- ↑ Lunde 1979, p. 70.

- ↑ Scott, Shirley Lynn. "Herb Mullin". trutv.com. truTV. Archived from the original on October 21, 2012. Retrieved January 30, 2022.

- 1 2 Torrey 2008, p. 35.

- ↑ Ressler & Shachtman 1992, p. 128.

- 1 2 Scott, Shirley Lynn. "Herb Mullin". truTV. Archived from the original on September 27, 2012. Retrieved January 28, 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ressler & Shachtman 1992, p. 129.

- 1 2 West, Don (August 5, 1973). "Mullin's 13 Dead Victims - Their Lives and Their Hopes" (PDF). S.F. Sunday Examiner & Chronicle. Santa Cruz Public Libraries.

- ↑ Lunde & Morgan 1980, p. 31.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ressler & Shachtman 1992, p. 130.

- ↑ Lunde 1979, p. 76.

- ↑ Lunde & Morgan 1980, p. 42.

- ↑ Anderson, Bruce (1973). "Mullin apparently knew murder victims" (PDF). Valley Press. Santa Cruz Public Libraries.

- ↑ Scott, Shirley Lynn (October 21, 2012). "Herb Mullin — The Hippie Massacre — Crime Library on truTV.com". Crime Library truTV. Archived from the original on October 21, 2012. Retrieved February 1, 2022.

- ↑ Bonvillian, Crystal (August 23, 2022). "Serial killer who said he killed to ward off earthquakes dies at 75". WPXI. Retrieved June 6, 2023.

- 1 2 Murray, Emerson (March 19, 2021). "State denies parole to Santa Cruz serial killer". Santa Cruz Sentinel. MediaNews Group. Retrieved January 31, 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Ressler & Shachtman 1992, p. 131.

- ↑ Lunde & Morgan 1980, p. 250.

- 1 2 Lunde 1979, p. 79.

- ↑ Scott, Shirley Lynn (October 21, 2012). "Herb Mullin — The Hippie Massacre — Crime Library on truTV.com". Archived from the original on October 21, 2012.

- 1 2 Scott, Shirley Lynn (October 21, 2012). "Herb Mullin — The Hippie Massacre — Crime Library on truTV.com". truTV. Archived from the original on October 21, 2012. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- ↑ Lunde & Morgan 1980, pp. 102–103.

- ↑ Ressler & Shachtman 1992, pp. 131–132.

- 1 2 Ressler & Shachtman 1992, p. 132.

- ↑ Lunde & Morgan 1980, p. 252.

- ↑ Lunde 1979, p. 80.

- ↑ Lunde & Morgan 1980, p. 310.

- ↑ Scott, Shirley Lynn (October 21, 2012). "Herb Mullin — Mentally Ill, but Sane? — Crime Library on truTV.com". truTV. Archived from the original on October 21, 2012. Retrieved February 1, 2022.

- ↑ Lunde & Morgan 1980, p. 311.

- ↑ Scott, Shirley Lynn (October 21, 2012). "Herb Mullin — Mentally Ill, but Sane? — Crime Library on truTV.com". truTV. Archived from the original on October 21, 2012. Retrieved January 31, 2022.

- ↑ "CALIFORNIAN GUILTY IN 10 MURDER CASES". The New York Times. August 20, 1973. Retrieved January 31, 2022.

- ↑ Lunde & Morgan 1980, p. 192.

- 1 2 Scott, Shirley Lynn (October 21, 2012). "Herb Mullin — Serial Killer Rivalry — Crime Library on truTV.com". truTV. Archived from the original on October 21, 2012. Retrieved January 30, 2022.

- ↑ "Serial Killer ed Kemper talks about Serial Killer Herbert Mullin which he met in Prison [Interview]". YouTube.

- ↑ Thornton, Terry (August 19, 2022). "Herbert Mullin Dies of Natural Causes". California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. Retrieved August 19, 2022.

Bibliography

- Lunde, Donald T. (1979). Murder and Madness. The Portable Stanford. New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0393009545. OCLC 258574271.

- Lunde, Donald T.; Morgan, Jefferson (1980). The Die Song: a Jurney Into the Mind of a Mass Murderer (1st ed.). New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-01315-3. OCLC 1033636320.

- Ressler, Robert K.; Shachtman, Tom (1992). Whoever Fights Monsters (1st ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0312078836. OCLC 25245627.

- Torrey, E. Fuller (2008). The Insanity Offense: How America's Failure to Treat the Seriously Mentally Ill Endangers Its Citizens (1st ed.). New York; London: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0393066586. OCLC 1335103780. Archived from the original on January 27, 2021.

- Schechter, Harold (2004). The Serial Killer Files (1st ed.). New York: Ballantine. ISBN 978-0345465665. OCLC 1151274027.

External links

- Official website Archived October 26, 2021, at the Wayback Machine