Henry A. Tandy | |

|---|---|

| Born | c. 1853 |

| Died | 1918 |

| Occupation(s) | Building contractor, entrepreneur, businessman |

| Years active | 1867-1918 |

| Organization | Tandy & Byrd |

| Known for | Contributions to Historic architecture |

| Spouse | Emma Brice |

| Children | Vertner Woodson Tandy, architect |

| Honours | Henry A. Tandy Centennial Park, Lexington, Kentucky |

Henry A. Tandy (c. 1853–1918) was an American building contractor and entrepreneur, specializing in decorative stone masonry and brickwork. Of African-American descent, he was born enslaved in Estill County, Kentucky, and rose to become one of the wealthiest African Americans in Kentucky by the early twentieth century.[1] His best-known commission is the historic Fayette County Courthouse in Lexington, Kentucky (1898–1900). In 2020, the downtown Cheapside Park, which is adjacent to the courthouse, was renamed the Henry A. Tandy Centennial Park in his honor.[2][3]

Biography

.jpg.webp)

After the Civil War and abolition of slavery in 1865 by the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, Tandy moved to Lexington. He was responsible for the grand Richardsonian Romanesque courthouse, completed in 1900, which features a dome structure and arches as well as artistic features incorporated into the stonework.[4] An example of adaptive re-use, the building now houses the Lexington Visitor Center as well as several restaurants.[5]

In Lexington, 1867, he first worked for local photographer John Mullen. However, he found his lifelong success through the building and contracting firm of Garrett D. Wilgus. There, he began as one of over 200 employees and was promoted to foreman in 1892. Tandy and Albert Byrd, his future business partner, ran the company beginning in the 1880s as Wilgus's health declined. After Wilgus's death in 1893, the two established Tandy & Byrd where Tandy was business manager and the face of the business and Byrd was the foreman. By 1894, the firm employed about 50 workers, both Blacks and whites. The Lexington Opera House, which is on the National Register of Historic Places, was among the firm's projects.[6] Other notable projects of the firm are the 1894 First National Bank building; the Carnegie Center for Literacy and Learning; the Natural Science Building at the State College now known as Miller Hall at the University of Kentucky; original structures at Eastern Kentucky University, Roark Hall and Sullivan Hall. He was known nationally, presenting papers and speaking at the National Negro Business League on the subject of contracting and building.[4][2][7]

He married Emma Brice, born 1855.[1] He was active in church and Sunday-school work in the Historic St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal Church, and the Masonic Order. In 1918, Tandy died of a septic infection in Lexington and was buried in Greenwood Cemetery, later named Cove Haven Cemetery.[7] [8] The couple's son, Vertner Woodson Tandy (1885-1949), became the first African American architect in the state of New York and a founder of Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity at Cornell University.[7]

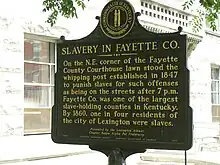

The impetus for the park renaming was started by a grassroots movement, Take Back Cheapside. Prominent in the park were two Confederate statues, Gen. John Hunt Morgan and John C. Breckinridge, the Confederate Secretary of War. These were installed during the Jim Crow era. The Morgan equestrian statue, 1911, was funded by both United Daughters of the Confederacy and the state of Kentucky. Breckinridge's contrapposto style statue, 1897, was also state funded. Cheapside Park was the site of one of the largest slave markets and was known for the sale of "fancy girls," women of mixed race sold for sexual purposes.[9]

The Lexington-Fayette Urban County Council voted unanimously in June, 2017 to move both statues to the Lexington Cemetery. In August, 2020 the council unanimously renamed the park for Tandy.[2]

References

- 1 2 "Notable Kentucky African Americans Database". Retrieved February 25, 2021.

- 1 2 3 Musgrave, Beth (August 28, 2020). "It's official. This downtown Lexington park is now Henry A. Tandy Centennial Park". The Lexington Herald Leader. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

- ↑ "Henry A. Tandy Centennial Park - Lexington, KY - VisitLex". www.visitlex.com. Retrieved 2023-02-19.

- 1 2 "Henry Tandy, the Man Who Built the Bluegrass". Bluegrass Trust for Historic Preservation. 2017. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

- ↑ Lofton, Shelby (February 19, 2021). "New signs installed for Henry A. Tandy Centennial Park in downtown Lexington". WKYT. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

- ↑ "Lexington KY, the Athens of the West". National Park Service. Retrieved February 26, 2021.

- 1 2 3 Smith, McDaniel, Hardin, Gerald L., Karen, John A. (2015). The Kentucky African American encyclopedia. Lexington, Ky: The University of Kentucky. pp. Location 24601–24602. ISBN 978-0-8131-6065-8. OCLC 907495488.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Cove Haven Cemetery historian shares findings about iconic Black figures". whas11.com. February 11, 2022. Retrieved 2023-02-23.

- ↑ Coleman, J. Winston (1970). Slavery times in Kentucky. Chapel Hill NC: University of North Caroline Press. OCLC 923578866.