Hannah Winbolt | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Hannah Oldham 1851 |

| Died | 1928 |

| Nationality | British |

Hannah Winbolt (1851–1928) was a prominent advocate for women's suffrage, giving speeches across the United Kingdom on the subject of women's rights from her perspective of a working woman. Known for being an effective orator, she was one of four women honoured retrospectively by Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council, in the naming of Suffragette Square, Stockport.[1]

Early life

Hannah Winbolt was born Hannah Oldham 1851, the youngest of three children, to William Oldham and his wife Esther in a cottage in Great Moor, Stockport.

She received a part-time education at a small local school only to the age of eight, before having to start work in service as a nurse. This lack of education for girls is something to which she would return to in her later campaigning.[2] At the age of twelve she began working in a cotton factory with other members of her family. During the cotton famine there was no work and they lived on poor relief. When she was sixteen, her health impaired by factory conditions, she went to live with her uncle, a silk weaver, who taught her his trade.[3]

In 1874 she married John O'Connor Winbolt, who was declared to be silk manufacturer. He was to become a keen supporter of her political work. They set up home at 12 Store Street and lived at various addresses in that street, developing the row of cottages along with a row fronting the main road (now the A6), including the Co-operative store on the corner. They never had children. The couple were living at 2 Store Street when John died after a long illness in 1920, and Hannah remained there until her death in 1928.[4]

The "Working Woman" suffragist

Travelling to Manchester by train with completed silk cloth to sell, she met Lydia Becker (1827-1890) a leader in the early British suffrage movement, best remembered for founding and publishing the Women's Suffrage Journal between 1870 and 1890. She asked Winbolt to sign a petition in support of women's suffrage. Uncertain as to what this might involve, Winbolt asked her uncle whether she should sign and he replied "Yes, lass, it's nobbut right that she signs; it's just fur t'rights of women, and rights ye maun have."[2] Becker saw in Winbolt a valuable asset to the suffrage movement as a representative of the "working woman", and recruited her to campaign for women's rights.[5]

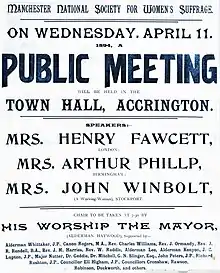

Winbolt first came to press attention in the early 1890s, when she was elected to the committee of the Union of Women's Liberal Associations for the Manchester area. She founded a branch of the association in Hazel Grove in 1891 and was described as "the spirited and able president".[6] Through her speaking engagements she met another well-known suffragist, Countess Alice Kearney,[7][8] who was to become a good friend, often staying with the Winbolts in Store Street when speaking in the area; She also stayed with Kearney at her Kensington home in London. On 18 February 1892, Winbolt was chosen by the Manchester National Society for Women's Suffrage to present to Parliament a petition by 4,292 Cheshire textile workers canvassed by the society, requesting women be appointed factory inspectors to improve the working conditions of women and children in the mills.[9][10]

Winbolt was elected as a "Progressive Candidate" for the executive committee of the Women's Liberal Federation in 1892. In 1893 she became a delegate to the National Women's Federation.

Over the next few years she spoke at many meetings around the country, on a range of topics concerning the rights of working women and children, in every case, much was made of the fact that she was a "working woman" herself. In addition to "Votes for Women",[11][12] she spoke and wrote on the education of children,[2] housing of the poor,[13] equal pay for women,[14][15] Home Rule,[16] fair trade,[17] the Manchester Association for the Abolition of State Regulation of Vice, and the campaigns for abolition of the House of Lords.[18]

In 1896, she was elected to the committee of the Union of Women's Liberal Associations giving "a rousing speech" to that year's meeting of the National Liberal Federation. Her public appearances were often lively affairs: Winbolt lecturing her middle-class audience in her Cheshire accent. She believed in humour as a way to get her message across, especially in response to hecklers. Reporting on a typical conference of the National Liberal Association the writer in The South Wales Daily noted: "Prominent features of the meeting were the utterances of Mrs. Winbolt, of Stockport, on the subjects of registration reform and the industrial position of women. Herself an experienced workwoman, with a natural gift of eloquence and a burning desire to help women who have to earn their living by manual labour, she delighted and encouraged her fellow-delegates with her vigorous advocacy for limitations on the hours which young half-timers have to work and the placing of an equality of women with men so far as employment was concerned".[19]

As previously mentioned, Hannah Winbolt and her husband helped in establishing a Cooperative Store in Great Moor. In 1894 she spoke at the opening meeting of the local Co-operative Women's Guild, very much a workers' movement.[20] The Co-operative News followed her activities.[17]

Later life

After Alice Kearney's death in 1899, Winbolt seems to have retired to some extent from public life though she was still speaking about how women workers were disadvantaged in the silk and cotton trades because they had no vote. In March 1902 she committed a Women's Suffrage Petition this time signed by 29,359 textile workers to Lancashire MPs to present to Parliament so earning her an even wider recognition in the press.[21][22][23]

By now, hers and others dedicated efforts were being taken up by a more militant suffrage movement which also originated in the Manchester area led by Emmeline Pankhurst. In July 1905 the Cheshire County News reported her speaking at a rally under the heading Suffragists at Stockport[24] but in the September she was sharing a platform with Adela Pankhurst and Annie Kenney under the heading ''Suffragettes in Stockport".[25] There is no evidence that Winbolt took part in civil disobedience, or damage to property, as practised by the Suffragettes. However letters to the local newspapers show her concern for those suffragettes suffering in prison.

In 1918 the Representation of the People Act came into law.[26] So, as a woman over 30 years of age and married to a husband whose property was worth a rateable yearly value of over £5, Winbolt was entitled to vote in a Parliamentary election. After his death, she inherited John's property so this entitled her to vote in her own right. She lived to see the Representation of the People Act 1928 extend the vote to all adults over the age of 21 before she died later that year.

Besides her speaking engagements, Winbolt wrote many letters to various newspapers, politicians and influential people on issues concerning women. She pasted copies of her published letters along with many cuttings from newspapers not fully attributed to sources into a large scrapbook now archived in Stockport Central Library.[27]

Winbolt was one of the four local women for whom Suffragette Square in Stockport was named on International Women's Day in 2018 (the others being Elizabeth Raffald, Elsie Plant and Gertrude Powicke).[1]

References

- 1 2 "Stockport's newest square honours four women on International Women's Day". Hits Radio. 8 March 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- 1 2 3 "Women Workers of Today – Mrs John Winbolt". Lloyds Weekly News. 15 September 1894.

- ↑ "Women who have won their way 1 - Mrs Winbolt". The People's Penny Stories No.89. 10 January 1908.

- ↑ Census Returns of England and Wales, 1851, 1861, 1871, 1881, 1891, 1911; the National Archives of the United Kingdom: Public Record Office

- ↑ Liddington and Norris, Liddington and Norris (2000)

- ↑ "Hazel Grove Women's Liberal Association: Amusing Speech by the President". The Woman's Herald. 14 March 1892.

- ↑ "Interview: Countess Alice Katherine Irma Percival Kearney". The Woman's Herald. 11 February 1893.

- ↑ "The Late Countess Alice Kearney". Liverpool Daily Post. 6 June 1899.

- ↑ "Workshop Inspection by Women: Deputation to the Home Secretary". The Woman's Herald. 25 January 1893.

- ↑ "Women as Factory Inspectors". The Woman's Herald. 1 June 1893.

- ↑ "Women's Suffrage". The Jarrow Express. 15 December 1893.

- ↑ "A Woman's a Woman for A'That: Mrs Winbolt on the Warpath: Wanted a Vacant Parliamentary Constituency". The Herald. 1 February 1893.

- ↑ "Housing of the Poor". The Carlisle Women's Liberal Association leaflet. 17 October 1895.

- ↑ "Gorton Women's Liberal Association: Address by Mrs John Winbolt". The Reporter. 9 October 1897.

- ↑ "Nuneaton Liberal Club: Political Aims and Social Necessities". The Observer. 7 May 1897.

- ↑ "The Denton Liberal Association". The Reporter. 18 March 1893.

- 1 2 "Women and Free Trade". The Cooperative News. 14 November 1903.

- ↑ "Peers and the People: Great Demonstration in Hyde Park". Penny Illustrated. 1 September 1894.

- ↑ "Mrs John Winbolt". The South Wales Daily. 18 January 1895.

- ↑ "Opening Meeting: Women's Cooperative Guild: Meeting at Great Moor". The Herald. 16 April 1894.

- ↑ "A Meeting in London". The Manchester Guardian. 19 February 1902.

- ↑ "Women's Franchise: Textile Workers and the Parliamentary Vote". The Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser. 19 February 1902.

- ↑ "The great Women's Suffrage Petition". Cooperative News. 15 March 1904.

- ↑ "Suffragists in Stockport". Cheshire County News. July 1905.

- ↑ "Suffragettes in Stockport". The Echo. 1 September 1905.

- ↑ Archives, The National. "The National Archives - Homepage". The National Archives. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ↑ "Hannah Winbolt and her Family: Davenport, Stockport : History". davenportstation.org.uk. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

- Liddington, Jill and Norris, Jill, "One Hand Tied Behind Us: The Rise of the Women's Suffrage Movement" Rivers Oram Press, 2000. ISBN 9781854891105