| Hall Place | |

|---|---|

Hall Place in 2012 | |

Location within Hampshire | |

| General information | |

| Location | Bentworth, Hampshire |

| Country | England |

| Coordinates | 51°09′19″N 1°03′11″W / 51.1552°N 1.0530°W |

| Completed | Early 14th century |

Hall Place (alternatively Hall Farm; formerly Bentworth Manor House or Bentworth Hall) is a manor house in the civil parish of Bentworth in Hampshire, England. It is about 300 metres (980 ft) southwest of St Mary's Church and 3.6 miles (5.8 km) northwest of Alton, the nearest town. Built in the early 14th century, it is a Grade II listed medieval hall house, known by various names through the centuries. It is 0.5 miles (0.80 km) from the current Bentworth Hall that was built in 1832.

History

In the 1086 Domesday Survey that was ordered by the first Norman king, William the Conqueror, Bentworth is listed as a parish in the Domesday entry for the Hundred of Odiham. Soon after Domesday, Bentworth became an independent manor in its own right. In about 1111 it was given by King Henry I "Beauclerc", the youngest son of William the Conqueror, together with four other English manors, to the diocese of Rouen and Geoffrey, Count of Anjou.[1] When King John began losing his possessions in Normandy he took back the ownership of many manors, including Bentworth. He then temporarily ceded the manor of Bentworth in 1207–8 to the Bishop of Winchester, Peter des Roches.[2] It was John who signed Magna Carta in June 1215 at Runnymede, staying at Odiham castle 10 km north-east of Bentworth the night before.[3] However, the manor was returned to the Archbishops of Rouen, who successively held the manor until 1316, when Edward II appointed Peter de Galicien custodian of the manor in that year.[4]

Some time after 1280, most likely 1320s, a new stone hall-house was built in Bentworth, possibly by the constable of Farnham castle, William de Aula.[5] In 1330, Matilda de Aula was given permission to have a private chapel at the hall. In 1336, ownership of the manor of Bentworth passed to William Melton, Archbishop of York.[4] Upon his death in 1340, he left his possessions to his nephew William de Melton, son of his brother, Henry.

In 1348, William de Melton obtained the king's permission to give his manor to William Edendon, Bishop of Winchester, and then ownership of the manor of Bentworth passed by marriage to the Windsor family, who had been constables of Windsor Castle. However, this hall was evidently returned to the Melton family, as it is mentioned among his possessions in an inquisition taken in 1362–3, and descended to his son, Sir William de Melton.[4] Sir William de Melton's son, John de Melton, inherited the house in 1399 and was still being recorded as owner in 1431.[4][6] He died in 1455, and was succeeded by his son (d.1474), then his grandson John Melton.[7] The manor of Bentworth itself was said to have remained in possession of the Windsor family for at least one hundred and fifty years.[4]

In 1590, Henry Windsor (1562–1605), the 5th Lord Windsor, sold the "sub-manor of Bentworth" to the Hunt family who had been tenants since the beginning of that century.[4] Ownership passed in 1610 to Sir James Woolveridge of Odiham and in 1651 to Thomas Turgis, a wealthy London merchant.[4] His son, also Thomas, was described as one of the richest commoners in England and in 1705, he left the manor of Bentworth to his relative William Urry, of Sheat Manor, Isle of Wight.[4]

In 1777, the Urry descendants were daughters Mary and Elizabeth, who married two Catholic brothers, Basil and William Fitzherbert of Swynnerton Hall, Staffordshire.[4] Their sister-in-law was Maria Fitzherbert, the secret wife of the Prince Regent, later King George IV.[8]

The 1800s

In about 1800, Mary Fitzherbert (who had 11 children) became owner of the Bentworth Hall Estate[4] and in 1832, the Estate was put up for auction by the Fitzherbert family. The auction was held at Garraway's Coffee House in Exchange Alley in the City of London, and was sold to Roger Staples Horman Fisher for about £6000. Almost immediately he started building the present Bentworth Hall about a mile south of the old Manor House on what was then open downland.

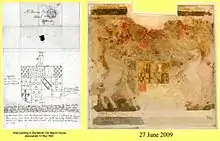

In 1841, wall paintings were discovered in Hall Place. These were described in a letter to Roger Horman Fisher with the postmark 17 November 1841. It was stamped: "1D Paid" (1D = one old penny, 1/240 of a pound) and addressed to: "R Horman Fisher Esq, Christ Church, Oxford". This letter is reproduced in the adjacent picture together with a photo of a crest that was part of the wall paintings; the photo being taken after a historical survey made by the owners of Hall Place in 2009. It also contains the following handwritten words describing the crest. On the left side of the letter it says: "Supporters Two Unicorns as are now born (sic) by Lord Plymouth". Right Side: "the bearings on the two last quarterings are broken, and cannot be made out". Underneath the drawing of the crest it says: "A well executed painting of these arms was discovered by removing the loose plaster from a wall in repairing the Old Manor House at Bentworth 10 Nov 1841. In the early part of the 14th century, the property belonged to Richard de Wyndsore, the ancestor of the present Earl of Plymouth. Through a marriage with the daughter and heiress of William de Bintworth and as the arms have not the Baronial helmet, and are without the Coronet, they must have been painted for one of the family between that period and before the first Lord Windsor was summoned to Parliament in 1529."

Architecture and fittings

Hall Place (the former Bentworth Hall or Manor) is a Grade II* listed medieval manor house, located along the main road of Bentworth. It was built in the early 14th century, with extensive additions in the 17th and 19th centuries.[9] The hall is believed to have been constructed by either the constable of Farnham Castle, William de Aula, or John of Bynteworth (Bentworth), and served for some time as the manor court.[5][9]

The hall has thick flint walls, gabled cross wings,[10] with a Gothic stone arch and 20th-century boarded door and two-storey porch.[9] Pevsner mentions that the porch is early 14th century.[11] The west wing of the house has a stone-framed upper window and very large attached tapered stack.[9] The east wing has sashes dated to the early 19th century.[9] The old fireplace remains in the north-facing room with its roll moulding and steeply pitched head.[5] Pevsner notes that this building is now a dairy.[11]

Grounds

A chapel in the grounds was part of the house complex. It was added soon after the construction of 1330 under the request of Matilda de Aula.[5]

References

- ↑ Creighton, Mandell; Winsor, Justin; Gardiner, Samuel Rawson (1919). The English Historical Review. Longman. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- ↑ Vincent, Nicholas (8 August 2002). Peter Des Roches: An Alien in English Politics, 1205–1238. Cambridge University Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-521-52215-1. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- ↑ Country Life. April 1965. p. 18. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Doubleday, Herbert Arthur, Page, William (1911). "A History of the County of Hampshire: Volume 4". accessed from British History Online. pp. 68–71.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 3 4 Emery, Anthony (2006). Greater Medieval Houses of England and Wales, 1300–1500: Southern England. Cambridge University Press. p. 309. ISBN 978-0-521-58132-5. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- ↑ Feud. Aids, ii. 1856. p. 314.

- ↑ Yorkshire Archaeological and Topographical Association (1886). The Yorkshire Archæological and Topographical Journal. The Association. p. 420. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- ↑ Munson, James (2001). Maria Fitzherbert: The Secret Wife of George IV. Constable. ISBN 978-0-09-478220-4. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Hall Farmhouse, Bentworth". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- ↑ "Hall Farm, Bentworth, Alton, Hampshire" (PDF). Thames Valley Archaeological Services. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- 1 2 Pevsner, Nikolaus; Lloyd, David (2002). The Buildings of England: Hampshire and the Isle of Wight. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09606-2.