Levant's sister ship in the Coventry class, HMS Carysfort | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | HMS Levant |

| Ordered | 6 May 1757 |

| Builder | Henry Adams, Buckler's Hard, Hampshire |

| Laid down | June 1757 |

| Launched | 6 July 1758 at Buckler's Hard |

| Completed | 16 June 1759 at Portsmouth Dockyard |

| Commissioned | October 1758 |

| In service |

|

| Out of service | 1779 |

| Honours and awards | Expedition against Martinique, 1762 |

| Fate | Broken up at Deptford Dockyard, September 1780 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | 28-gun Coventry-class sixth-rate frigate |

| Tons burthen | 595 34⁄94 bm |

| Length | |

| Beam | 33 ft 11 in (10.3 m) |

| Depth of hold | 10 ft 6 in (3.20 m) |

| Sail plan | Full-rigged ship |

| Complement | 200 |

| Armament |

|

HMS Levant was a 28-gun sixth-rate frigate of the Coventry class, which saw Royal Navy service against France in the Seven Years' War, and against France, Spain and the American colonies during the American Revolutionary War. Principally a hunter of privateers, she was also designed to be a match for small French frigates, but with a broader hull and sturdier build at the expense of some speed and manoeuvrability. Launched in 1758, Levant was assigned to the Royal Navy's Jamaica station from 1759 and proved her worth by defeating nine French vessels during her first three years at sea. She was also part of the British expedition against Martinique in 1762 but played no role in the landings or subsequent defeat of French forces at Fort Royal.

The frigate was decommissioned following Britain's declaration of peace with France in 1763, but returned to service in 1766 for patrol duties in the Caribbean. Decommissioned for a second time in 1770, she was reinstated at the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War and sent to the Mediterranean as part of a small British squadron based at Gibraltar. Over the next three years she captured or sank a total of fourteen enemy craft including an 18-gun American privateer. In 1779 she brought home news of an impending Spanish assault on Gibraltar, ahead of Spain's declaration of war on Great Britain.

The ageing frigate was finally removed from Navy service later that year, and her crew discharged to other vessels. She was broken up at Deptford Dockyard in 1780, having secured a total of 31 victories over 21 years at sea.

Construction

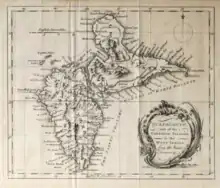

%252C_Levant_(1758)_RMG_J6599.jpg.webp)

Levant was an oak-built 28-gun sixth rate, one of 19 vessels forming part of the Coventry class of frigates.[1][2] As with others in her class she was loosely modelled on the design and dimensions of HMS Tartar, launched in 1756 and responsible for capturing five French privateers in her first twelve months at sea.[3] Orders from Admiralty to build the Coventry-class vessels were made after the outbreak of what was later called the Seven Years' War, at a time when the Royal Dockyards were fully engaged in constructing or fitting-out the Navy's ships of the line. Consequently, and despite some Navy Board misgivings, contracts for most Coventry-class vessels were issued to private shipyards, with an emphasis on rapid completion.[4]

The contract for Levant's construction were issued on 20 May 1757 to shipwright Henry Adams of Buckler's Hard in Hampshire. It was stipulated that work should be completed within ten months for the 28-gun vessel measuring approximately 586 tons burthen. Subject to satisfactory completion, Adams would receive a comparatively modest fee of £9.5s per ton to be paid through periodic imprests drawn against the Navy Board.[5][6][lower-alpha 1] As private shipyards were not subject to rigorous naval oversight, the Admiralty also granted authority for "such alterations withinboard as shall be judged necessary" in order to cater to the preferences or ability of individual shipwrights.[3][4]

After consultation with Admiralty, Adams took advantage of this freedom to make four substantive changes to the Tartar design. The ship's wheel was moved from behind the mizzen mast to before it to improve the helmsman's line of sight.[7][8] The tiller was relocated, from an exposed position on the quarterdeck to a safer location belowdecks and near the stern.[8] The vessel's hawseholes were relocated from the lower to the upper deck to allow additional storage space inside the hull.[9] Finally, in recognition of the vessel's likely role in chasing small enemy craft, the leading pair of gunports were moved from the sides of the vessel to the bow in order to form a battery of chase guns.[7]

Levant's keel was laid down in June 1757 but work proceeded slowly and the vessel was not ready for launch until July 1758. As built, Levant was 118 ft 5 in (36.1 m) long with a 97 ft 4 in (29.7 m) keel, a beam of 33 ft 11 in (10.34 m), and a hold depth of 10 ft 6 in (3.2 m). After Adams' modifications, she was of 595 34⁄94 tons burthen, nearly ten tons more than the figure specified in the contract.[5] Her armament comprised 24 nine-pounder cannon located along her gun deck, supported by four three-pounder cannon on the quarterdeck and twelve 1⁄2-pounder swivel guns ranged along her sides.[3] The Admiralty-designated complement was 200, comprising two commissioned officers – a captain and a lieutenant – overseeing 40 warrant and petty officers, 91 naval ratings, 38 Marines and 29 servants and other ranks.[10][lower-alpha 2] Among these other ranks were four positions reserved for widow's men – fictitious crew members whose pay was intended to be reallocated to the families of sailors who died at sea.[10]

The vessel was named after the Levant, an area of the eastern Mediterranean. This continued a Board of Admiralty tradition, dating to 1644, of naming ships for geographic features. Overall, ten of the nineteen Coventry-class vessels, including Levant, were named after well-known regions, rivers or towns.[1][11] With few exceptions the remainder of the class were named after figures from classical antiquity, following a more modern trend initiated in 1748 by John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich, in his capacity as First Lord of the Admiralty.[1][11][lower-alpha 3] In sailing qualities Levant was comparable with French frigates of equivalent size, but with a shorter and sturdier hull and greater weight in her broadside guns. She was also comparatively broad-beamed which, when coupled with Adams' modifications, provided ample space for provisions, the ship's mess and a large magazine for powder and round shot.[lower-alpha 4] Taken together these characteristics enabled Levant to remain at sea for long periods without resupply.[13][14] She was built with broad and heavy masts which balanced the weight of her hull, improved stability in rough weather and made her capable of carrying more sail. The disadvantages of this heavy design were seen in reduced manoeuvrability and slower speed in light winds.[15]

Seven Years' War

1758–1760

Levant was launched on 6 July 1758 and sailed to Portsmouth Dockyard for fitting-out and to take on armament and crew. She was formally commissioned in October, entering Royal Navy service during the early stages of the Seven Years' War against France.[5] Command was assigned to Captain William Tucker, a nephew of London philanthropist Ralph Allen, and previously the commander of the sixth-rate HMS Sphinx.[16][17] There were delays in mustering sufficient crew, and the frigate was not finally ready to put to sea until June 1759. On 14 June Captain Tucker received orders to take position off Guadeloupe and the Leeward Islands,[5] there to join a squadron commanded by Commodore John Moore.[18] Levant set sail for this assignment on 23 July.[5][19]

The British squadron, of which Levant was part, was tasked with disrupting French trade through the Caribbean and hunting privateers. However the frigate saw little action in her first six months in the region; French trade had virtually ceased since the outbreak of war with Britain, while a smallpox outbreak killed some among Levant's crew. In November 1759, Levant and the Antigua-based privateer Bristol captured two French vessels loaded with coffee and sugar heading to trade at the neutral Dutch island of Sint Eustatius.[20] It was not until early 1760 that Levant defeated her first armed opponent, a 14-gun French privateer which was sunk with the loss of 120 of her crew.[21] Thereafter combat was more frequent. Two small privateers were captured in early 1760 – the 8-gun Poissan Volante and the 12-gun St Pierre – and these vessels and their crews were delivered into British custody on the Leeward Islands.[18] In June Pickering, a British merchantman previously captured by the French, was retaken and sailed to Antigua as Levant's prize.[22] A further victory followed on 29 June with the capture of French privateer Le Scipio,[5][23] after which Levant was put into harbour in Antigua for resupply. One contemporary source at this time records her as carrying only 20 of her 28 guns.[24] She returned to sea before the end of the year, capturing the privateer L'Union on 18 December.[5]

1761–1762

"The Clerk of our Ship is dead, and several others of the Ship's Company; many people die daily of the Small Pox, which distemper is all over the island of Antigua ...

[The French] dependence is on their privateers; the seas swarm with them."

— Extract of a letter from a crew member of Levant, describing conditions aboard in 1759–60.[21]

British military successes in European waters in 1760 offered freedom for the Navy to support offensive operations in the Caribbean in the following year. In January Major General Robert Monckton set sail from North America to the Caribbean with 2,000 men and four ships of the line, for a planned invasion of French Dominica.[25] Levant saw little action in advance of Monckton's arrival and captured only one vessel, the privateer La Catherine, on 15 February.[26] Monckton arrived in Antigua shortly after this capture; Captain Tucker was then deputised to carry the general aboard Levant for a visit to the various Leeward Island settlements while the invasion force assembled at Guadeloupe.[27] Monckton departed the Leeward Islands in April and Levant resumed her hunt for privateers, capturing La Dulcinée on 13 July and L'Aventurier six days later.[5] Another French privateer, Conquerant, was captured on 19 November while Levant was in company with her fellow Royal Navy frigate, the 26-gun Emerald.[28] At least four other vessels were also taken in this period; Superbe, Polly, Petit-Creolle and Elizabeth.[29]

Dominica having fallen to Monckton's forces in June, the British then set their sights on the French stronghold of Martinique. Britain's Secretary of State for the Southern Department, Sir William Pitt, concluded that Martinique's capture would be the decisive battle for control of the Caribbean, and instructed that all available resources be committed to its invasion. An army of 13,000 troops was assembled, supported by a fleet under Admiral George Rodney.[30] Levant was added to Rodney's sizeable command in late 1761 and sailed as part of the expedition in January 1762.[5][31] She was present when the British landings commenced but is not recorded as having engaged with enemy forces either there or in the subsequent French defeat at Fort Royal between 25 January and 3 February.[5]

Levant then returned to her station off the Leeward Islands, arriving there on 10 February. Captain Tucker had fallen ill with gout, and on 20 February he was replaced by Captain John Laforey, previously of the sixth-rate HMS Echo.[5][32][lower-alpha 5] Levant made one capture under Laforey's command, and her last victory in that war, when she defeated French privateer La Fier on 13 May 1762.[5][35]

| Date | Ship | Nationality | Type | Fate | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| March 1760 | Not recorded | French | Privateer, 14 guns | Sunk | [21] |

| By April 1760 | Poissan Volante | French | Privateer, 8 guns | Captured | [18] |

| 29 April 1760 | Le Saint Pierre | French | Privateer, 12 guns | Captured | [5][18] |

| After April 1760 | Superbe | French | Not recorded | Captured | [29][18] |

| After April 1760 | Polly | Not recorded | Not recorded | Captured | [29][18] |

| After April 1760 | Petit-Creolle | French | Not recorded | Captured | [29][18] |

| After April 1760 | Elizabeth | Not recorded | Not recorded | Captured | [29][18] |

| June 1760 | Pickering | British | Merchant vessel | Recaptured | [22] |

| 29 June 1760 | Le Scipio | French | Privateer, 10 guns | Captured | [5][23] |

| 19 November 1760 | Conquerant | French | Privateer | Captured | [28] |

| 18 December 1760 | L'Union | French | Privateer | Captured | [5] |

| 15 February 1761 | La Catherine | French | Privateer, 10 guns | Captured | [5][26] |

| 13 July 1761 | La Dulcinée | French | Privateer | Captured | [5] |

| 19 July 1761 | L'Aventurier | French | Privateer | Captured | [5] |

| 13 May 1762 | Le Fier | French | Privateer | Captured | [5] |

Peacetime service

The 1763 Treaty of Paris brought an end to the war between Britain and France, and Levant was subsequently declared surplus to the Navy's needs. She was in poor condition; Captain Laforey reported to Admiralty that rats had eaten through the hull and substantial work would be required to keep the ship afloat.[36] Repairs were commenced, but by April 1763 Laforey had departed the vessel and command was transferred to Captain Molyneux Shuldham for the voyage back to England. Restored to seaworthiness, Levant reached Portsmouth Dockyard in August, where she was decommissioned and her crew discharged or reassigned.[5][37]

There were rumours that Levant would swiftly return to active service,[38] but these proved unfounded and she remained tied up at Portsmouth. Her hull and fittings were surveyed in late 1763 to determine maintenance requirements, but no repairs were made.[5] In September 1763 a member of her skeleton crew was robbed and murdered at Liphook, a village some distance from Portsmouth.[39]

Levant returned to Navy service in 1766 under the command of Captain Basil Keith, and was assigned to patrol and convoy duties on the Navy's Jamaica Station. In August she docked at Deptford to take on crew and supplies, setting sail for the Caribbean on 28 November.[5][40] Levant held her Jamaica post for three years, but this extensive service in tropical waters left her in poor condition. In 1770 she returned to Deptford Dockyard where she was decommissioned and hauled out of the water for rebuilding. The work was granted to shipwright John Dudman and took six months from November 1770 to April 1771. Repair and rebuilding expenses were £5,869 with an additional £3,059 for fitting-out, considerably more than the vessel's original construction cost of £5,423.[5]

The rebuilt frigate was recommissioned in August 1771 under Captain Samuel Thompson. After four months in home waters she was assigned to the Navy's Mediterranean squadron and took up position off Gibraltar in January 1772. Levant remained at this station for three years, her uneventful service broken only by a 1773 transfer of command from Captain Thompson to Captain George Murray, the son of former Jacobite commander Lord Murray.[5]

American Revolutionary War

1775–1777

"Levant ordered her to strike; the Captain of the Privateer said she would not, upon which he was told by the Levant's people that they would in a few minutes sink her ... the Privateer immediately struck without firing a gun."

— A contemporaneous account of the capture of the 14-gun American privateer General Montgomery, March 1777.[41]

Levant returned to Portsmouth in early 1775, but put to sea again on 22 June amid the early stages of the American Revolutionary War.[5] Captain Murray's orders were to join a Mediterranean squadron under the overall command of Captain Robert Mann, which was given the task of intercepting merchant vessels suspected of supplying American rebels. While at sea Murray also took the opportunity to train his crew in seamanship and battle techniques, in preparation for future enemy engagement.[42] In March 1776 she anchored in the Bay of Algiers where the Dey, or local ruler, received her warmly and provided the crew with supplies of bread, vegetables, and three live sheep.[42]

Mediterranean trade was busy, and Levant took part in halting and examining vessels with crews of various nationalities including Dutch, Genoese, Spanish, and the British Caribbean.[42] Neutral shipping was permitted to continue on its way. However Levant detained a South Carolina merchantman named Dolphin in October 1776, on suspicion of being a supply vessel for the rebels, and sent her into Gibraltar along with her cargo of rice.[43] In November 1776 Levant secured a substantial prize with the capture of another South Carolina vessel, Argo,[44] carrying rice and indigo worth £37,200.[45] Argo was to have exchanged her cargo in Bordeaux for clothing and medicine to supply the American rebellion.[46]

Further success followed in early 1777 with the capture of the 18-gun American privateer General Montgomery.[5] News had reached England that this vessel was off the island of Madeira in March, having sailed from the Port of Philadelphia in February with a crew of 100 men. Levant was sent in pursuit, with her crew sighting the General Montgomery at midday on 8 March. Captain Murray ordered Levant to fly false colours, hoisting a Dutch flag to avoid alerting the privateer's crew.[41] General Montgomery had also disguised herself by flying a British flag. For several hours the Americans allowed Levant to draw near, finally turning to flee when Murray fired a warning shot. A seven-hour chase ensued, extending into the night with the two ships often within musket shot but unable to bring their broadside cannon to bear. At around 1:00 am the wind strengthened and Levant was able to overhaul her prey, forcing the out-gunned Americans to surrender. Nine of General Montgomery's crew enlisted aboard Levant; the remainder were conveyed to Portsmouth where they remained imprisoned in poor conditions until the end of the war.[47][48]

1778–1780

Levant continued her Mediterranean patrols in 1778 and was rewarded on 24 March with the recapture of a British merchantman which had been bound for Newfoundland when seized by an American privateer off Gibraltar.[49] On the same day as this capture, Levant fell into company with the 28-gun frigate HMS Enterprise. Her captain, Sir Thomas Rich, advised that he was pursuing USS Revenge, a 22-gun American privateer with three captured merchant ships in tow. On 21 March the privateer had surprised and destroyed Enterprise's tender before escaping into the night. Rich had given chase for the next three days; Murray now added Levant to the hunt and the two British frigates set courses to windward and leeward of the Americans' likely path. Both sailed through the night without sighting their prey. In the morning of 25 March they encountered one of Revenge's prizes, the 16-gun British merchantman Hope, which promptly surrendered and was returned to Gibraltar.[49] Revenge herself eluded capture and was later reported as having escaped to the neutral Spanish port of Cádiz.[50]

France entered the war against Britain after signing a formal Treaty with the United States in March 1778. There was a subsequent reorganization of Royal Navy forces in the Mediterranean, with Levant joining a squadron of four other vessels based in Gibraltar under the overall direction of Admiral Robert Duff. Of this squadron, Levant was the second largest, behind only Duff's 60-gun flagship HMS Panther.[51] In July Levant encountered and captured Robert, an American merchant vessel that had been bound for Boston with a cargo of salt.[52] In August she took her first French prize of the War – a merchantman with a cargo of tobacco – and recaptured the British schooner Lively, which had previously been seized by an American privateer off Scotland's Western Islands.[53] Two more French prizes followed: Victorieux seized en route to Marseilles, and Duchess of Grumont, which surrendered off Toulon. The captured vessels were sent under guard to Gibraltar.[54]

These ongoing victories belied the changing conditions applicable to Levant's hunt for enemy vessels off Gibraltar. American vessels had become scarce, especially since Spain had closed her ports to them in the winter of 1777 in retaliation for privateer attacks on Spanish ships.[55] French trading vessels remained at sea but were occasionally accompanied by naval escorts large enough to prevent their capture by Gibraltar's small Royal Navy squadron.[56] Levant was careened on a beach at Gibraltar over Christmas 1778 and then returned to sea, but her next capture was not until 14 March 1779 when in company with Captain Rich's Enterprise she seized a French vessel, Thésée.[56][57] A further victory followed on 1 April when Levant, still in company with Enterprise, took Eclair, a French xebec carrying wine and brandy from Marseilles.[58][59][lower-alpha 6]

On 12 April 1779 Spain signed the Treaty of Aranjuez with France, setting terms for a joint military alliance against Britain. Despite the Treaty Spain delayed the formal declaration of war until June, to give time for better co-ordination of its battle fleet.[60][61] In the interim Levant engaged and defeated a Spanish privateer whose crew were caught in the act of boarding a British merchant ship. A brief exchange of cannon fire holed the Spanish vessel below the waterline, sinking her; Levant rescued the majority of her crew and transported them to prison in Gibraltar.[62]

Captain Murray then took Levant on a cruise to hunt for French or American vessels off Cadiz. While pursuing this task in June 1779 he ran across the Spanish battle fleet, comprising 32 ships of the line and two frigates, heading south towards an unknown destination.[63] Spain was still nominally a neutral power and after a brief exchange of pleasantries the Spanish fleet left Levant unmolested and continued on its way. Murray immediately set sail for England to report that the Spanish were at sea, pausing off Land's End on 17 July to capture the French privateer La Revanche.[64] Levant finally reached Portsmouth in late July but by this time Murray's news of the Spanish fleet was out of date; Spain had already declared war on Britain and her fleet had reached Gibraltar to commence an extended siege.[60][65]

| Date | Ship | Nationality | Type | Fate | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| October 1776 | Dolphin | American | Merchant vessel | Captured | [43] |

| 28 November 1776 | Argo | American | Merchant vessel | Captured | [44][45][46] |

| 9 March 1777 | General Montgomery | American | Privateer, 18 guns | Captured | [5][41] |

| 24 March 1778 | Not recorded | British | Merchant vessel | Recaptured | [49] |

| 24 March 1778 | Hope | British | Merchant vessel | Recaptured | [49] |

| By late July 1778 | Robert | American | Merchant vessel | Captured | [52] |

| August 1778 | Not recorded | French | Merchant vessel | Captured | [53] |

| August 1778 | Lively | British | Merchant vessel | Recaptured | [53] |

| September 1778 | Victorieux | French | Merchant vessel | Captured | [54] |

| September 1778 | Duchess of Grumont | French | Merchant vessel | Captured | [54] |

| 14 March 1779 | Thésée | French | Not recorded | Captured | [57] |

| 1 April 1779 | Eclair | French | Merchant vessel | Captured | [56][59] |

| By June 1779 | Not recorded | Spanish | Privateer | Sunk | [62] |

| 17 July 1779 | La Revanche | French | Privateer | Captured | [5][64] |

| October 1779 | Nine Colliers | British | Merchant vessel | Recaptured | [57] |

| October 1779 | Velenza de Alcantara | Spanish | Privateer, 20 guns | Captured | [66] |

Final voyages

Murray was ordered to take Levant back to sea immediately, departing Portsmouth on 27 July as escort to a convoy of merchant vessels bound for the Yorkshire port of Kingston upon Hull.[67] The ageing frigate then briefly joined a small Navy squadron on patrol off Brighton before setting sail for the Spanish coast.[68][66] On 5 August she took part in the recapture of a British merchant vessel, Nine Colliers.[57] She was off Cadiz in October 1779 when she won her final victory of the war, capturing the 20-gun Spanish privateer Velenza de Alcantara along with 200 of her crew.[66]

But by month's end Levant was back in Portsmouth, where she was decommissioned and her crew discharged to other vessels.[5] She had been at sea for 21 years, outlasting all but four of her sister ships in the Coventry class.[69] Her captain, George Murray, was reassigned to command the 30-gun fifth rate frigate HMS Cleopatra; he was promoted to admiral in 1794, and died in 1797.[70][42]

Despite Levant's age there was still some consideration of restoring her to active service. As late as 1 August 1780 there were newspaper reports that she was "repairing and will soon be fit for sea",[71] but no repairs were made. On 16 August, Admiralty issued orders that she be sailed to Deptford Dockyard where, on 27 September, she was broken up.[5] Her passing was mourned by her crew, with their sentiments recorded by Levant's former first lieutenant, Erasmus Gower, that "having captured so considerable a number of prizes ... few vessels, perhaps, have ever quitted a station with more éclat respecting herself, and more regret from the officers and other persons concerned, who derived advantage from her good fortune and the activity of her people."[72]

References

Notes

- ↑ Adams' £9.5s fee compared unfavourably with an average £9.0s per ton sought by Thames River shipwrights to build 24-gun Royal Navy vessels over the previous decade,[6] but was less than the average £9.9s fee for Coventry-class vessels built in private shipyards between 1756 and 1765.[1]

- ↑ The 29 servants and other ranks provided for in the ship's complement consisted of 20 personal servants and clerical staff, four assistant carpenters, an assistant sailmaker and four widow's men. Unlike naval ratings, servants and other ranks took no part in the sailing or handling of the ship.[10]

- ↑ The exceptions to these naming conventions were Hussar, Active and the final vessel in the class, Hind[1][12]

- ↑ Levant's dimensional ratios 3.57:1 in length to breadth, and 3.3:1 in breadth to depth, compare with standard French equivalents of up to 3.8:1 and 3:1 respectively. Royal Navy vessels of equivalent size and design to Levant were capable of carrying up to 20 tons of powder and shot, compared with a standard French capacity of around 10 tons. They also carried greater stores of rigging, spars, sails and cables, but had fewer ship's boats and less space for the possessions of the crew.[13]

- ↑ Tucker subsequently resigned from the Navy and returned to England.[33] He inherited £10,000 on the death of his uncle Ralph Allan in 1764, and a further £5,000 when Allan's widow died in 1766.[17][34] Tucker's own poor health persisted and he died in 1770 at the age of 43.[33]

- ↑ Other sources indicate Eclair was captured on 31 March 1779.[57]

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 Winfield 2007, pp. 227–231

- ↑ Gardiner 1992, p. 17

- 1 2 3 Winfield 2007, p. 227

- 1 2 Rosier, Barrington (2010). "The Construction Costs of Eighteenth-Century Warships". The Mariner's Mirror. 92 (2): 164. doi:10.1080/00253359.2010.10657134. S2CID 161774448.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 Winfield 2007, pp. 229–230

- 1 2 Baugh 1965, pp. 255–256

- 1 2 Gardiner 1992, p. 76

- 1 2 Gardiner, Robert (1977). "The Frigate Designs of 1755–57". The Mariner's Mirror. 63 (1): 54. doi:10.1080/00253359.1977.10659001.

- ↑ Gardiner 1992, p. 18

- 1 2 3 Rodger 1986, pp. 348–351

- 1 2 Manning, T. Davys (1957). "Ship Names". The Mariner's Mirror. Portsmouth, United Kingdom: Society for Nautical Research. 43 (2): 93–96. doi:10.1080/00253359.1957.10658334.

- ↑ Winfield 2007, p. 240

- 1 2 Gardiner 1992, pp. 115–116

- ↑ Gardiner 1992, pp. 107–108

- ↑ Gardiner 1992, pp. 111–112

- ↑ Winfield 2007, pp. 257–258

- 1 2 "Deaths". The Scots Magazine. 1 July 1764. p. 55. Retrieved 5 March 2017 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "London". The Caledonian Mercury. Edinburgh: Walter Ruddiman, John Richardson and Company. 19 July 1760. p. 1. Retrieved 20 July 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ "London". The Newcastle Courant. Newcastle, United Kingdom: John White. 23 June 1759. p. 1. Retrieved 17 July 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ "St. John's in Antigua". The Pennsylvania Gazette. 7 February 1760.

- 1 2 3 "Extract of a Letter from On Board the Levant Man of War, at Antigua, dated March 20". The Manchester Mercury. Manchester, United Kingdom: Joseph Harrop. 6 May 1760. p. 1. Retrieved 19 July 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- 1 2 "London". The Caledonian Mercury. Edinburgh: Walter Ruddiman, John Richardson and Company. 6 September 1760. p. 2. Retrieved 22 July 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- 1 2 "Admiralty Office, February 28". The Derby Mercury. Derby, United Kingdom: S. Drewry. 27 February 1761. p. 3. Retrieved 22 July 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ "Extract of a Letter from St John's in Antigua, to a Merchant in Cork, July 23, 1760". The Derby Mercury. Derby, United Kingdom: S. Drewry. 17 October 1760. p. 1. Retrieved 22 July 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ Robson 2016, p. 173

- 1 2 "Extract of a Letter from St Christopher's". The Caledonian Mercury. Edinburgh: Walter Ruddiman, John Richardson & Company. 27 April 1761. p. 2. Retrieved 19 July 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ "Extract of a Letter from St John's, Antigua, March 11". The Caledonian Mercury. Edinburgh: Walter Ruddiman, John Richardson and Company. 9 May 1761. p. 2. Retrieved 22 July 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- 1 2 "No. 10279". The London Gazette. 15 January 1763. p. 2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "No. 10476". The London Gazette. 4 December 1764. p. 2.

- ↑ Robson 2016, pp. 174–175

- ↑ "Extract of a Letter from Guadeloupe, December 7". The Derby Mercury. Derby, United Kingdom: S. Drewry. 5 February 1762. p. 1. Retrieved 23 July 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ Winfield 2007, p. 276

- 1 2 "Leeds, November 20". The Leeds Intelligencer. Leeds, United Kingdom: Griffith Wright and Son. 20 November 1770. p. 3. Retrieved 6 March 2017 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ "London". The Caledonian Mercury. Edinburgh: Walter Ruddiman, John Richardson and Company. 22 August 1764. p. 2. Retrieved 6 March 2017 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ "Letter from Charlestown, South Carolina, July 14". The Caledonian Mercury. Edinburgh: Walter Ruddiman, John Richardson and Company. 23 August 1762. p. 3. Retrieved 23 July 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ Rodger 1986, p. 70

- ↑ "Extract of a Letter from Portsmouth, August 14". The Caledonian Mercury. Edinburgh: Walter Ruddiman, John Richardson and Company. 20 August 1763. p. 2. Retrieved 23 July 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ "London". The Derby Mercury. Derby, United Kingdom: S. Drewry. 19 August 1763. p. 3. Retrieved 23 July 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ "Conditions". The Derby Mercury. Derby, United Kingdom: S. Drewry. 23 September 1763. p. 2. Retrieved 23 July 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ "Edinburgh". The Caledonian Mercury. Edinburgh: Walter Ruddiman, John Richardson and Company. 1 September 1766. p. 3. Retrieved 30 July 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- 1 2 3 "London, Saturday April 12". The Derby Mercury. Derby, United Kingdom: John Drewry. 11 April 1777. p. 2. Retrieved 31 July 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- 1 2 3 4 "Finding Aid for HMS Levant and HMS Arethusa Log Book, 1775–1777". William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan. 2015. Archived from the original on 29 August 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- 1 2 Clark (ed.) et al. 2014, p. 939

- 1 2 "Admiralty-Office". Saunders's News Letter. J. Poris. 20 December 1776. p. 1. Retrieved 31 July 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- 1 2 "Admiralty-Office, December 13". The Hampshire Chronicle. Southampton: J. Linden and J. Hodson. 16 December 1776. p. 3. Retrieved 31 July 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- 1 2 "Extract of a Letter from a Merchant at Lisbon, to his Brother in Birmingham, dated December 1, 1776". The Derby Mercury. Derby, United Kingdom: John Drewry. 13 December 1776. p. 4. Retrieved 31 July 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ Captain George Murray RN to Captain William Hay, HMS Alarm, 14 March 1777. Cited in Clark (ed.) et al. volume 8, 1980, pp. 676–677

- ↑ Clark (ed.) et al. volume 11, 2005, pp. 888–892

- 1 2 3 4 "Extract of a Letter from Gibraltar, March 27". The Ipswich Journal. Ipswich, United Kingdom: J. Shave, E. Craighton and S. Jackson. 2 May 1778. p. 2. Retrieved 1 August 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ Clark (ed.) et al. volume 12, p. 525

- ↑ "The Following is a Correct List of the Marine Forces of Great Britain with their Present Stations". The Hampshire Chronicle. Winchester: J. Wilkes. 14 September 1778. p. 4. Retrieved 4 August 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- 1 2 "Dublin". Hibernian Journal: Or, Chronicle of Liberty. Dublin: T. M'Donnell. 27 July 1778. p. 3. Retrieved 4 August 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- 1 2 3 "Extract of a Letter from Gibraltar, August 19". The Caledonian Mercury. Edinburgh: John Robertson. 28 September 1778. p. 3. Retrieved 20 July 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- 1 2 3 "Dublin". Saunders's News Letter. J. Poris. 1 October 1778. p. 2. Retrieved 4 August 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ Clark (ed.) et al. volume 11, p. 860

- 1 2 3 "Extract of a Letter from Gibraltar, January 31". The Manchester Mercury. Manchester, United Kingdom: Joseph Harrop. 16 March 1779. p. 1. Retrieved 6 August 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "No. 12105". The London Gazette. 29 July 1780. p. 2.

- ↑ "Ships Taken from the French and Americans". The Leeds Intelligencer. Leeds, United Kingdom: Griffith Wright and Son. 11 May 1779. p. 3. Retrieved 6 August 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- 1 2 "Foreign Intelligence". Saunders's News Letter. J. Poris. 26 May 1779. p. 1. Retrieved 6 August 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- 1 2 Dull 2009, p. 102

- ↑ Hunt 1905, p. 196

- 1 2 "London, June 18". Saunders's News Letter. J. Poris. 24 June 1779. p. 1. Retrieved 6 August 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ "Sunday's Post". The Ipswich Journal. J. Shave and S. Jackson. 31 July 1779. p. 1. Retrieved 13 August 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- 1 2 "Home News". The Hampshire Chronicle. Southampton, United Kingdom: J. Linden and J. Hodson. 2 August 1779. p. 3. Retrieved 13 August 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ "London, July 24". Saunders's News Letter. J. Poris. 30 July 1779. p. 1. Retrieved 13 August 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- 1 2 3 "London, October 21". Cumberland Pacquet, and Ware's Whitehaven Advertiser. John Ware & Son. 26 October 1779. p. 2. Retrieved 13 August 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ "London, July 30". Saunders's News Letter. J. Poris. 5 August 1779. p. 1. Retrieved 13 August 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ "London, August 27". Saunders's News Letter. J. Poris. 2 September 1779. p. 1. Retrieved 13 August 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ Winfield 2007, pp. 227–232

- ↑ "Murray, George (1741–1797)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/40510. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ "A Complete List of the Navy of Great Britain, with the Names of the Captains of each Ship, the Fleets on the Different Stations, and the Ships Fitting Out, In Ordinary and Building". The Scots Magazine. 1 August 1780. p. 4. Retrieved 14 August 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ Gower 1800, p. 8

Bibliography

- Baugh, Daniel A. (1965). British Naval Administration in the Age of Walpole. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691624297.

- Clark, William Bell; Morgan, William James; Crawford, Michael J., eds. (1980). Naval Documents of the American Revolution. Vol. 8. New York: American Naval Records Society. OCLC 630221256.

- Clark, William Bell; Morgan, William James; Crawford, Michael J., eds. (1996). Naval Documents of the American Revolution. Vol. 10. New York: American Naval Records Society. ISBN 9780160452864.

- Clark, William Bell; Morgan, William James; Crawford, Michael J., eds. (2005). Naval Documents of the American Revolution. Vol. 11. New York: American Naval Records Society. OCLC 767761391.

- Clark, William Bell; Morgan, William James; Crawford, Michael J., eds. (2014). Naval Documents of the American Revolution. Vol. 12. New York: American Naval Records Society. OCLC 904424124.

- Dull, Jonathan (2009). The Age of the Ship of the Line: The British and French Navies, 1650–1815. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 9780803235182.

- Gardiner, Robert (1992). The First Frigates: Nine-Pounder and Twelve-Pounder Frigates, 1748–1815. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0851776019.

- Gower, Erasmus (1800). Biographical Memoir of Sir Erasmus Gower, Admiral of the White Squadron of His Majesty's Fleet. Portsea, United Kingdom: Bunney and Gold. OCLC 669118545.

- Hunt, William (1905). The History of England from the Accession of George III to the Close of Pitt's First Administration, 1760–1801. Vol. 10. London: Longmans, Green and Company. OCLC 457312784.

- Robson, Martin (2016). A History of the Royal Navy: The Seven Years War. London: Taurus. ISBN 9781780765457.

- Rodger, N. A. M. (1986). The Wooden World: An Anatomy of the Georgian Navy. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0870219871.

- Winfield, Rif (2007). British Warships of the Age of Sail 1714–1792: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. Barnsley, United Kingdom: Seaforth. ISBN 9781844157006.