| M72 LAW | |

|---|---|

An M72 LAW in extended position | |

| Type | Anti-tank rocket-propelled grenade launcher[1] |

| Place of origin | United States |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1963–present |

| Used by | See Operators |

| Wars |

|

| Production history | |

| Designer | FA Spinale, CB Weeks and PV Choate |

| Designed | Patent filed 1963 |

| Manufacturer | |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 2.5 kg (5.5 lb) (M72A1–3) / 3.6 kg (7.9 lb) (M72A4–7)[5] |

| Length | 630 mm (24.8 in) (unarmed) 881 mm (34.67 in) (armed) |

| Caliber | 66 mm (2.6 in) |

| Muzzle velocity | 145 m/s (480 ft/s) |

| Effective firing range | 200 m (660 ft), 220 m (720 ft) (A4–7) |

Detonation mechanism | Point-initiated, base-detonated |

The M72 LAW (light anti-tank weapon, also referred to as the light anti-armor weapon or LAW as well as LAWS: light anti-armor weapons system) is a portable one-shot 66 mm (2.6 in) unguided anti-tank weapon. The solid rocket propulsion unit was developed in the newly-formed Rohm and Haas research laboratory at Redstone Arsenal in 1959,[6] and the full system was designed by Paul V. Choate, Charles B. Weeks, Frank A. Spinale, et al. at the Hesse-Eastern Division of Norris Thermador. American production of the weapon began by Hesse-Eastern in 1963, and was terminated by 1983; currently it is produced by Nammo Raufoss AS in Norway and their subsidiary, Nammo Talley, Inc. in Arizona.[7]

In early 1963, the M72 LAW was adopted by the U.S. Army and U.S. Marine Corps as their primary individual infantry anti-tank weapon, replacing the M31 HEAT rifle grenade and the M20A1 "super bazooka" in the U.S. Army. It was subsequently adopted by the U.S. Air Force to serve in an anti-emplacement and anti-armor role in airbase defense.[8][note 1]

In the early 1980s, the M72 was slated to be replaced by the FGR-17 Viper. However, the Viper program was canceled by Congress and the M136 AT4 was adopted instead. At that time, its nearest equivalents were the Swedish Pskott m/68 (Miniman) and the French SARPAC.

Background

The increased importance of tanks and other armored vehicles in World War II caused a need for portable infantry weapons to deal with them. The first to be used (with limited success) were Molotov cocktails, flamethrowers, satchel charges, jury-rigged landmines, and specially designed magnetic hollow charges. All of these had to be used within a few meters of the target, which was difficult and dangerous.

The U.S. Army introduced the bazooka, the first rocket-propelled grenade launcher. Despite early problems, it was a success and was copied by other countries.

However, the bazooka had its drawbacks. Large and easily damaged, it required a well-trained two-man crew. Germany developed a one-man alternative, the Panzerfaust, having single-shot launchers that were cheap and requiring no special training. As a result, they were regularly issued to Volkssturm home guard regiments. They were very efficient against tanks during the last days of World War II.

The M72 LAW is a combination of the two World War II weapons. The basic principle is a miniaturized bazooka, while its light weight and cheapness rival the Panzerfaust.

Description

_voor_eenmalig_gebruik_(2086-067-006).jpg.webp)

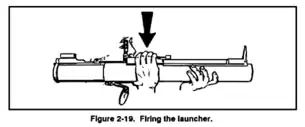

The weapon consists of a rocket within a launcher consisting of two tubes, one inside the other. While closed, the outer assembly serves as a watertight container for the rocket and the percussion-cap firing mechanism that activates the rocket. The outer tube contains the trigger, the arming handle, front and rear sights, and the rear cover. The inner tube contains the channel assembly, which houses the firing pin assembly, including the detent lever. When extended, the inner tube telescopes outward toward the rear, guided by the channel assembly, which rides in an alignment slot in the outer tube's trigger housing assembly. This causes the detent lever to move under the trigger assembly in the outer tube, both locking the inner tube in the extended position and cocking the weapon. Once armed, the weapon is no longer watertight, even if the launcher is collapsed into its original configuration. It is a line of sight weapon with a range around 200 meters (660 ft).[9]

When fired, the striker in the rear tube impacts a primer, which ignites a small amount of powder that "flashes" down a tube to the rear of the rocket and ignites the propellant in the rocket motor. The rocket motor burns completely before leaving the mouth of the launcher, producing a backblast of gases around 1,400 °F (760 °C). The rocket propels the 66 mm (2.6 in) warhead forward without significant recoil. As the warhead emerges from the launcher, six fins spring out from the base of the rocket tube, stabilizing the warhead's flight. The early LAW warhead, developed from the M31 HEAT rifle grenade warhead, uses a simple piezoelectric fuze system. On impact with the target, the front of the nose section is crushed, causing a microsecond electric current to be generated, which detonates a booster charge located in the base of the warhead, which sets off the main warhead charge. The force of the main charge forces the copper liner into a directional particle jet that, in relation to the size of the warhead, is capable of a massive penetration.

A unique mechanical set-back safety on the base of the detonator grounds the circuit until the missile has accelerated out of the tube. The acceleration causes the three disks in the safety mechanism to rotate 90° in succession, ungrounding the circuit; the circuit from the nose to the base of the detonator is then completed when the piezoelectric crystal is crushed on impact.

The weapon can be fired from inside buildings as long as the structure is at least 3.7 by 4.6 m (12 by 15 ft) in size, which is about 50 cubic meters (1,800 cu ft) in volume, and has sufficient ventilation.[10][11] The Department of the Army previously rated the weapon as safe to fire from enclosure, but this rating was removed in 2010 after the introduction of the safer AT4 CS.[12] However, some modern variants of the LAW are specifically designed with fire-from-enclosure (FFE) capability.[13]

In late 2021, Nammo unveiled the concept of a multi-rotor unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) equipped with a LAW. The tube is mounted facing downward, enabling the drone operator to fire on tanks and armored vehicles from a top attack position while remaining 3 to 4 km (1.9 to 2.5 mi) away.[14]

Ammunition

M72 LAWs were issued as prepackaged rounds of ammunition. Improvements to the launcher and differences in the ammunition were differentiated by a single designation. The original M72 warhead penetrated 30 cm (12 in) of armor.[15][16]

A training variant of the M72 LAW, designated M190, also exists. This weapon is reloadable and uses the 35 mm (1.4 in) M73 training rocket. A subcaliber training device that uses a special tracer cartridge also exists for the M72. A training variant used by the Finnish armed forces fires 9 mm (0.35 in) tracer rounds.

The US Army tested other 66 mm rockets based on the M54 rocket motor used for the M72. The M74 TPA (thickened pyrophoric agent) had an incendiary warhead filled with TEA (triethylaluminum); this was used in the M202A1 FLASH (flame assault shoulder weapon) four-tube launcher. The XM96 RCR (riot control rocket) had a CS gas-filled warhead for crowd control and was also intended for use with the M202, though the rocket never entered service.

Service history

Australia

The M72 rocket has been in Australian service since the Vietnam War.[17][18] Currently, the Australian Defence Force uses the M72A6 variant, known as the "light direct fire support weapon",[19] as an anti-structure and secondary anti-armor weapon. The weapon is used by ordinary troops at the section (squad) level and complements the heavier 84 mm (3.3 in) Carl Gustav recoilless rifle and Javelin missile, which are generally used by specialized fire support and anti-armor troops.[20]

Canada

As of 21 February 2023, Canada has supplied 4500 M72s to Ukraine for use in the Russo-Ukrainian War.[21] These are of the M72A5-C1 designation.[22]

Finland

The M72 LAW is used in the Finnish Army (some 70,000 pieces), where it is known under the designations 66 KES 75 (M72A2, no longer in service) and 66 KES 88 (M72A5). In accordance with the weapon's known limitations, a pair of "tank-buster" troops crawl to a firing position around 50 to 150 meters (160 to 490 ft) away from the target, bringing with them four to six LAWs, which are then used in rapid succession until the target is destroyed or incapacitated. Due to its low penetration capability, it is used mostly against lightly-armored targets. The M72 is the most common anti-tank weapon in the Finnish Army. Finland has recently upgraded its stocks to the M72 EC LAW Mk.I version. It is designated 66 KES 12[23] Claimed penetration for the M72 EC LAW is 450 mm (18 in) of rolled homogeneous armor steel plate, nearly twice that of the M72A2.[24] It also fields the bunker-buster version that contains 440 g (0.97 lb) of DPX-6 explosive, named M72 ASM RC, and locally designated 66 KES 12 RAK. The oldest version of the 66 KES 75 is now retired.[25]

Norway

In late February 2022, the Norwegian government announced that it intended to donate "up to 2,000" M72 LAW units from their reserve stocks to Ukraine, in response to the Russian invasion.[26] On March 30, 2022, the Norwegian Defence Ministry said that 2,000 more units will be sent to Ukraine.[27]

Taiwan

The Republic of China Army (Taiwan) uses the M72 as a secondary anti-armor weapon. It is used primarily as a backup to the Javelin and M136 (AT4) anti-tank weapons. The weapon was later reverse-engineered into the "Type 1 66 mm anti-tank rocket" but is more-popularly nicknamed as the "Type 66 rocket" due to its caliber.

Turkey

The Turkish Army uses a locally built version by Makina ve Kimya Endustrisi Kurumu, called HAR-66 (Hafif Antitank Roketi, 'light antitank rocket'), which has the performance and characteristics of a mix of an M72A2 and an A3. Turkey also indigenously developed an anti-personnel warhead version of HAR-66 AP and called it "Eşek Arısı" ('wasp').[28]

United Kingdom

The British Army had used the NAMMO M72 under the designation "rocket 66 mm HEAT L1A1" but it was replaced by the LAW 80 during the 1980s.[29] It was used in action during the 1982 Falklands War, mainly to suppress Argentinian defensive positions at close range;[30] however, it was also used against an assault amphibious vehicle during the initial invasion and was one of the weapons which damaged the warship ARA Guerrico in the invasion of South Georgia.[31] The M72 rocket was reintroduced into British service under the Urgent Operational Requirement program, with the M72A9 variant being designated the light anti-structure munition (LASM).[32][33][34]

United States

During the Vietnam and post-Vietnam periods, all issued LAWs were recalled after instances of the warhead exploding in flight, sometimes injuring the operator. After safety improvements, part of the training and firing drills included the requirement to ensure that the words "w/coupler" were included in the text description stenciled on the launcher, which indicated that the launcher had the required safety modifications.[note 2]

With the failure of the M72's intended replacement, the Viper, in late 1982 Congress ordered the US Army to test off-the-shelf light antitank weapons and report back by the end of 1983. In partnership with Raufoss AS, Talley Defense offered the M72E5, which offered increased range, penetration and better sights; this was tested along with five other light anti-armor weapons in 1983. Despite the improvements that the M72E5 offered, the AT4 was chosen to replace the M72.[35][note 3]

Although generally thought of as a Vietnam War–era weapon that has been superseded by the more-powerful AT4, the M72 LAW found new popularity in the operations by the U.S. Army, the U.S. Marine Corps, and Canadian Army in Iraq and Afghanistan. The lower cost and lighter weight of the LAW, combined with a scarcity of modern heavy armored targets and the need for an individual assault weapon versus an individual anti-armor weapon, made it ideal for the type of urban combat seen in Iraq and mountain warfare seen in Afghanistan. In addition, a soldier can carry two LAWs on a mission as opposed to a single AT4.[36]

The U.S. Marine Corps Systems Command at Quantico, Virginia, placed a $15.5-million fixed contract order with Talley Defense for 7,750 M72A7s, with delivery to be completed in April 2011.[37][38] The M72A7 LAW is an improvement on previous versions, including an improved rocket motor for a higher velocity to accurately engage targets past 200 m (660 ft), an insensitive munitions warhead to reduce the likelihood of an accidental explosion, and a Picatinny rail to mount laser pointers and night sights. The LAW was useful in Afghanistan as a small and light rocket system for use against short- and medium-range targets by foot patrols in the difficult terrain and high elevations of the country.[9] The U.S. military was still purchasing LAW rockets as of January 2015. In 2018 it was reported that an upgrade for the LAW was being developed that would improve the fire control system as well as largely eliminate the weapon's back blast, allowing the weapon to be used more safely from within a confined space.[39]

Vietnam

Several M72A1 and M72A2 LAWs captured during the Vietnam War have been put into service with the chemical force of the Vietnam People's Army. The launchers are upgraded to be able to fire multiple times and are armed with M74 incendiary rounds.

Variants

| Designation | Description | US designation | International designation |

|---|---|---|---|

| M72 | 66 mm (2.6 in) Talley single-shot disposable rocket launcher; pre-loaded with HEAT rocket | M72 | |

| M72A1 | Improved rocket motor | M72A1 | L1A1 (UK) |

| M72A2 | Improved rocket motor, higher penetration | M72A2 | 66 KES 75 (Finland), L1A3 (UK) |

| M72A3 | M72A2 variant; safety upgrades | M72A3 | |

| M72A4 | Rocket optimized for high penetration; uses improved launcher assembly | M72A4 | |

| M72A5 | M72A3 variant; uses improved launcher assembly | M72A5 | 66 KES 88 (Finland) |

| M72A6 | Warhead modified for lower penetration but increased blast effect; uses improved launcher assembly | M72A6 | |

| M72A7 | M72A6 variant, insensitive-explosive (PBXN-9) version for US Navy | M72A7 | |

| M72A7 Graze[40] | A7 variant with super-sensitive Graze fuze, restricted from training use (combat-only) | M72A7 with Graze | |

| M72A8 | Anti-armor warhead with fire-from-enclosure (FFE) propulsion | M72A8 | |

| M72A9 | Blast-optimized HE warhead, DPX-6 explosive | Light anti-structure missile (LASM) [UK] | |

| M72A10 | Anti-structure warhead with FFE propulsion | M72A10 | |

| M72E8 | M72A7 variant; FFE-capable rocket motor; uses improved launcher assembly | ||

| M72E9 | M72 variant; rocket with improved anti-armor capability; uses improved launcher assembly | ||

| M72E10 | M72 variant; HE-frag rocket; FFE-capable; uses improved launcher assembly | ||

| M72E11[41] | Airburst M72 | ||

| M72 EC | Enhanced capacity, increased anti-armor performance, 315 grams PBXW-11 explosive | 66 KES 12 (Finland) | |

| M72 ASM RC | Reduced-caliber 45 mm (1.8 in) anti-structure rocket, 0.4 kg (0.88 lb) DPX-6 explosive | 66 KES 12 RAK (Finland) | |

| M247[42] | 70 mm (2.75 in) rocket warhead using M72A2 warhead components, 910 g (2.0 lb) composition B explosive | M247 | |

| HAR-66 | Turkish variant, mix of A2 and A3 features | HAR-66 (Turkey) | |

| M72AS | 21 mm (0.83 in) reusable trainer | M72AS | |

| M190[42] | 35 mm (1.4 in) training variant, fires M73 practice rocket | M190 |

Armor penetration

| Variant | Penetration (mm) |

|---|---|

| M72/A1 | 200 |

| M72A2/A3/A5 | 300 |

| M72A4 | 350 |

| M72A6/A7 | 150 |

| M72 EC Mk.1 | 450 |

| M72 EC Mk.2 | 300 |

| M247 | ~300[note 4] |

Specifications (M72A2 and M72A3)

Launcher

- Length:

- Extended: less than 1 m (39 in)

- Closed: 0.67 m (26 in)

- Weight:

- Complete M72A2: 2.3 kg (5.1 lb)

- Complete M72A3: 2.5 kg (5.5 lb)

- Firing mechanism: percussion.

- Front sight: reticle graduated in 25 m range increments

- Rear sight: peep sight adjusts automatically to temperature change

Rocket

- Caliber: 66 mm (2.6 in)

- Length: 508 mm (20.0 in)

- Weight: 1.8 kg (4.0 lb)

- Muzzle velocity: 145 m/s (480 ft/s)

- Minimum range (combat): 10 m (33 ft)

- Minimum arming range: 10 m (33 ft)

- Maximum range: 1,000 m (3,300 ft)

- Penetration: 300 mm (12 in)[43]

Maximum effective ranges

- Stationary target: 200 m (220 yd)

- Moving target: 165 m (180 yd)

- Beyond these ranges there is less than a 50% chance of hitting the target.

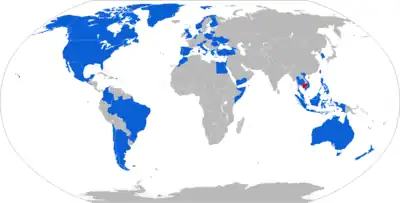

Operators

Current operators

Argentina: M72A3 variant.[44]

Argentina: M72A3 variant.[44].svg.png.webp) Australia: M72A6 variant.[45]

Australia: M72A6 variant.[45] Austria[45]

Austria[45].svg.png.webp) Belgium[45]

Belgium[45] Brazil: M72A2 variant used by navy[46]

Brazil: M72A2 variant used by navy[46].svg.png.webp) Canada[45] M72A5 variant, labeled as M72A5-C1

Canada[45] M72A5 variant, labeled as M72A5-C1 Colombia[47]M72A3 variant

Colombia[47]M72A3 variant Chile: M72A3 variant.[45] Used by the Chilean Army and the Chilean Marine Corps. New variant used by the latter force reported in 2018.[48]

Chile: M72A3 variant.[45] Used by the Chilean Army and the Chilean Marine Corps. New variant used by the latter force reported in 2018.[48] Denmark: M72A7 variant, since 2018 M72 EC[49][50]

Denmark: M72A7 variant, since 2018 M72 EC[49][50] Egypt[51]

Egypt[51] El Salvador[52]

El Salvador[52] Israel[53][54]

Israel[53][54] Italy: M72A5 variant since 2007

Italy: M72A5 variant since 2007 Malaysia[55]

Malaysia[55] Finland[45]

Finland[45] Georgia[56]

Georgia[56] Greece[57]

Greece[57] Iraq[58]

Iraq[58] Kosovo:

Kosovo: Kyrgyzstan:[59][60] The weapon was shown during new military equipment presentation recently which were sent with Turkey's official representative to hand them Kyrgyz officials.

Kyrgyzstan:[59][60] The weapon was shown during new military equipment presentation recently which were sent with Turkey's official representative to hand them Kyrgyz officials. Luxembourg[45]

Luxembourg[45] Lithuania: Lithuanian National Defence Volunteer Forces[61]

Lithuania: Lithuanian National Defence Volunteer Forces[61] Mexico: First seen in September 2018[62]

Mexico: First seen in September 2018[62] Morocco[45]

Morocco[45] Netherlands[45]

Netherlands[45] New Zealand[45]

New Zealand[45] Norway[45]

Norway[45] Philippines[63]

Philippines[63] Poland: On July 7, 2022, Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of National Defense Mariusz Błaszczak announced the delivery of several thousand M72 EC MK1s.[64]

Poland: On July 7, 2022, Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of National Defense Mariusz Błaszczak announced the delivery of several thousand M72 EC MK1s.[64] Portugal[65]

Portugal[65] Romania[66]

Romania[66] Somalia[67]

Somalia[67] South Korea[45]

South Korea[45] Spain: M72A3 variant.[45]

Spain: M72A3 variant.[45] Syrian National Coalition[68]

Syrian National Coalition[68] Taiwan[45]

Taiwan[45] Thailand[45]

Thailand[45] Turkey[45]

Turkey[45] Ukraine: delivered to Ukraine by Canadian, Danish and Norwegian Armed Forces (and possibly several others[69]), as part of the military aid during the 2022 Russian Invasion.[70][71][72]

Ukraine: delivered to Ukraine by Canadian, Danish and Norwegian Armed Forces (and possibly several others[69]), as part of the military aid during the 2022 Russian Invasion.[70][71][72] United Kingdom: Used by the British Army from the 1970s to the early 1990s.[73] The M72A9 variant was reintroduced into service for the Afghanistan war.[74] due to its light weight, lower cost and greater portability.

United Kingdom: Used by the British Army from the 1970s to the early 1990s.[73] The M72A9 variant was reintroduced into service for the Afghanistan war.[74] due to its light weight, lower cost and greater portability. United States[45]

United States[45] Yemen[45]

Yemen[45] Vietnam[45]

Vietnam[45]

Former users

FNLA[75]

FNLA[75] Cambodia[65]

Cambodia[65] China: launchers captured and used in Sino-Vietnamese War and Sino-Vietnamese conflicts, replaced by the PF-89, PF-98 and DZJ-08 anti-tank grenade launcher.[2]

China: launchers captured and used in Sino-Vietnamese War and Sino-Vietnamese conflicts, replaced by the PF-89, PF-98 and DZJ-08 anti-tank grenade launcher.[2] South Vietnam [76]

South Vietnam [76]

See also

Similar weapons

Notes

- ↑ The U.S. Army partially replaced the Super Bazooka not only with the M72 LAW, but also the M67 recoilless rifle, and U.S. Marines kept the Super Bazooka in service until the late 1960s.

- ↑ Some reports state these instances were caused by misfires due to water in the flash tube and by unproven rumors of sabotage at the manufacturing plant during the Vietnam War.

- ↑ Various reports in 1983 stated that during the congressionally-mandated tests the first M72E5 tested had an accuracy problem, because its larger-diameter rocket motor interfered with the deployment of all the stabilizing fins after leaving the launcher. The manufacturers have since made modifications that have solved that problem.

- ↑ TM 43-0001-30 states the M247 has "approximately the same" penetration as the M72.

References

- ↑ Rottman, Gordon L. (15 March 2011). The Rocket Propelled Grenade. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781849081542. Retrieved 14 March 2018 – via Google Books.

- 1 2 "浴火重生——对越自卫反击战对我国轻武器发展的影响". 23 Sep 2014. Retrieved 5 Aug 2022.

- ↑ Katz, Sam; Russell, Lee E (25 Jul 1985). Armies in Lebanon 1982–84. Men-at-Arms 165. Osprey Publishing. p. 8. ISBN 9780850456028.

- ↑ "The Coconut Revolution (2001, 50min) (480x360)". youtube.com. Archived from the original on 9 March 2016. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ↑ Cooke, Gary. "M72 Light Anti-tank Weapon System (LAW)". www.inetres.com. Gary's U.S. Infantry Weapons Reference Guide.

- ↑ E. T. DeRieux et al. Final Report – Development of LAW Propulsion Unit, R&H RARD, Technical Report No. S-12, December 1959

- ↑ "M72 products" Archived 2015-03-21 at the Wayback Machine. Nammo Talley, Inc. Retrieved September 25, 2014.

- ↑ Mary T. Cagle "History of the TOW Missile System", page 10, U.S. Army, 1977.

- 1 2 Modernizing and equipping the force (Part 1) Archived 2014-04-27 at the Wayback Machine – Army.mil, 30 December 2010

- ↑ "SQUAD WEAPONS B2E2657 Student Handout" (PDF). trngcmd.marines.mil. UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS.

- ↑ "FM 3–23.25 SHOULDER-LAUNCHED MUNITIONS" (PDF). bits.de. DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY.

- ↑ "TM 3–23.25(FM 3–23.25) Shoulder-Launched Munitions" (PDF). armypubs.army.mil. Department of the Army.

- ↑ Gonzales, Matt. "MARINE CORPS RELEASES SOLICITATION FOR ROCKET SYSTEM". marcorsyscom.marines.mil. MCSC Office of Public Affairs and Communication.

- ↑ Dalløkken, Per Erlien (29 October 2021). "Luftbåren M72: Nammo monterer raketter på drone – kan være et billig og effektivt panservernvåpen". Tu.no (in Norwegian). Teknisk Ukeblad.

- ↑ "FM 7-7" (PDF). www.bits.de. March 1985. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 June 2018. Retrieved 10 November 2018.

- ↑ "LIGHT ANTIARMOR WEAPONS" (PDF). DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY. 30 August 2001. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 January 2013. Retrieved 10 November 2018.

- ↑ REL22751 – M72 (L1A2F1) Rocket Launcher Archived 2012-05-20 at the Wayback Machine – Australian War Memorial. Accessed December 2010.

- ↑ Weapons Used by Infantry Rifle Sections Archived 2010-11-30 at the Wayback Machine – diggerhistory.info. Accessed December 2010.

- ↑ "Air Force technology: Equipment – Defence Jobs Australia". Defencejobs.gov.au. Archived from the original on November 29, 2012. Retrieved 2013-01-01.

- ↑ REMEMBER WHEN.... WE GOT ATGWS? Archived March 11, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Tristin Hopper, Tristin Hopper (21 February 2023). "Here's everything Canada has sent to Ukraine since Russia invaded". nationalpost.com. National Post. Retrieved 21 February 2023.

- ↑ "Canadian donations and military support to Ukraine". Canadian National Defence. 2023-06-24.

- ↑ "Enhanced capability for anti-tank measures by new light anti-tank weapon -".

- ↑ "Nammo Ammunition Handbook: Edition 2" Archived 2016-03-15 at the Wayback Machine, Nordic Ammunition Company (Nammo), page 131, 2014.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-03-06. Retrieved 2019-04-03.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ "Norway to provide weapons to Ukraine". www.regjeringen.no. Office of the Prime Minister. February 28, 2022. Retrieved March 7, 2022.

- ↑ "Norway Sends More Anti-Tank Weapons to Ukraine". U.S. News.

- ↑ "MKEK Makina ve Kimya Endüstrisi Kurumu / Mechanical and Chemical Industry Corporation". Mkek.gov.tr. Archived from the original on March 14, 2012. Retrieved 2013-01-01.

- ↑ "Jane's Infantry Weapons 1995–1996", page 686

- ↑ Badsey, Stephen; Whittick, Robin Paul, eds. (2004). The Falklands Conflict Twenty Years on: Lessons for the Future. London: Routledge. p. 289. ISBN 978-0415350303.

- ↑ Middlebrook, Martin (2012). The Falklands War. Barnsley, UK: Pen & Sword Military. pp. 49 & 60. ISBN 978-1-84884-636-4.

- ↑ "LASM – British Army Website". Army.mod.uk. Archived from the original on November 23, 2012. Retrieved 2013-01-01.

- ↑ "Oh, the Horror, the Horror". Archived from the original on 2008-03-26. Retrieved 2008-03-26.

- ↑ "M72 Light Anti-tank (sic) Weapon System (LAW)". Gary's U.S. Infantry Weapons Reference Guide. Archived from the original on 2004-12-21. Retrieved 2004-12-23.

- ↑ D. Kyle, Armed Forces Journal International, November 1983, "Viper Dead, Army Picks AT-4 Antitank Missile", page 21

- ↑ "Marines Fought the LAW, and the LAW Won". Defenseindustrydaily.com. 2005-03-10. Archived from the original on 2013-01-25. Retrieved 2013-01-01.

- ↑ Antal, John (2010). "Packing a Punch: America's Man-Portable Antitank Weapons". Military Technology. 3/2010: 88. ISSN 0722-3226.

- ↑ "Light Assault Weapon (LAW)". FBO.gov. Archived from the original on 2012-02-14. Retrieved 2008-07-05.

- ↑ Jared Keller his iconic Vietnam-era rocket launcher just got a major upgrade — and Marines say it's a 'game changer', Business Insider, 02.04.18, accessed 15.05.2020

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-05-23. Retrieved 2019-05-23.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-06-06. Retrieved 2019-05-23.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - 1 2 "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-07-12. Retrieved 2019-05-23.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ "FM 7-7: The Mechanized Infantry Platoon and Squad (APC)" (PDF). Headquarters, Department of the Army. 15 March 1985. pp. B-5–B-6.

- ↑ "wiw_sa_argentina - worldinventory". 2016-11-24. Archived from the original on 2016-11-24. Retrieved 2023-03-01.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Jones, Richard D. Jane's Infantry Weapons 2009/2010. Jane's Information Group; 35 edition (January 27, 2009). ISBN 978-0-7106-2869-5.

- ↑ "Tráfico de armas". ISTOÉ Independente (in Brazilian Portuguese). 2003-07-16. Retrieved 2022-11-18.

- ↑ "Sistemas Antitanque del Ejercito Nacional de Colombia". América Militar: información sobre defensa, seguridad y geopolítica (in European Spanish). 2012-04-09. Retrieved 2023-11-20.

- ↑ García, Nicolás (20 September 2018). "The Chilean Army exhibits its Airbus Cougar and Ecureuil in Santiago". Infodefensa.com. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ↑ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "M/72: Test af dysekanon". YouTube.

- ↑ "Panserværnsvåben M72 ECLAW" [Anti-armor weapon M72 ECLAW] (in Danish). The Danish Armed Forces. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ↑ Sof, Eric (2023-04-02). "M72 LAW: A Lightweight, Single-Shot Anti-Tank Weapon". Spec Ops Magazine. Retrieved 2023-11-15.

- ↑ "El Salvador". Military Technology World Defence Almanac: 60. 2005. ISSN 0722-3226.

- ↑ "Israel: LAW on Order". Archived from the original on 30 August 2017. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ↑ "IDF – Israel Defense Forces : Special weaponry of the Nahal Brigade". Archived from the original on 2012-12-31. Retrieved 2012-12-19.

- ↑ "Army Getting M72 LAW – Malaysian Defence". Retrieved 2019-11-08.

- ↑ "Armament of the Georgian Army". Geo-army.ge. Archived from the original on 2012-03-09. Retrieved 2013-01-01.

- ↑ "Γενικό Επιτελείο Στρατού". Archived from the original on 8 January 2016. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ↑ Vining, Miles (June 19, 2018). "ISOF Arms & Equipment Part 4 – Grenade Launchers & Anti-Armour Weapons". armamentresearch.com. Archived from the original on July 28, 2018. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- ↑ Jane's infantry weapons, 2009-2010 2009/2010. Richard, August 14- Jones, Leland S. Ness (35th ed.). Coulsdon: Jane's Information Group. 2009. ISBN 978-0-7106-2869-5. OCLC 769660119.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ President; Parliament; Cabinet; Politics; Economy; Society; Analytics; Regions; Emergencies. "Armed Forces of Kyrgyzstan receive military equipment". Информационное Агентство Кабар. Retrieved 2022-08-08.

- ↑ "Jungtinės Amerikos Valstijos Lietuvos kariuomenei perduoda prieštankinių granatsvaidžių M72LAW | Lietuvos kariuomenė". Jungtinės Amerikos Valstijos Lietuvos kariuomenei perduoda prieštankinių granatsvaidžių M72LAW | Lietuvos kariuomenė (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 2021-04-12.

- ↑ de Cherisey, Erwan (24 September 2018). "Mexican military shows off new equipment". IHS Jane's 360. Paris. Archived from the original on 24 September 2018. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- ↑ "13 Victorious tactical offensives launched in Southern Tagalog!". www.philippinerevolution.net. Archived from the original on November 7, 2007.

- ↑ "Polska kupiła tysiące granatników jednorazowych". defence24.pl. 7 July 2022.

- 1 2 Eric Sof (2 April 2023). "M72 LAW: A Lightweight, Single-Shot Anti-Tank Weapon". Sepc Ops Magazine.

- ↑ "Buletinul Contractelor de Achiziții Publice, anul 5, Nr.1" (PDF) (in Romanian). DPA (Armaments Department). 11 June 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 March 2012. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ↑ Small Arms Survey (2012). "Surveying the Battlefield: Illicit Arms In Afghanistan, Iraq, and Somalia". Small Arms Survey 2012: Moving Targets. Cambridge University Press. p. 342. ISBN 978-0-521-19714-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-08-31. Retrieved 2018-08-30.

- ↑ "Insight – Syria rebels get light arms, heavy weapons elusive". Reuters. 2012-07-13. Archived from the original on 25 August 2017. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ↑ "Rundown: Western Anti-Tank Weapons For Ukraine". OvertDefense. 8 March 2022. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- ↑ "Canada prepared to welcome an 'unlimited number' of Ukrainians fleeing war, minister says". CBC News. 3 March 2022. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- ↑ "Danmark donerer 2.700 skulderbårne panserværnsvåben til Ukraine" [Denmark donates 2,700 light anti-armor weapons to Ukraine] (in Danish). The Danish Armed Forces. 27 February 2022. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ↑ "Norge sender militærutstyr og våpen til Ukraina" [Norway sends military equipment og weapons to Ukraine] (in Norwegian). The Norwegian Armed Forces. 28 February 2022. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ↑ Owen, William F. (2007). "Light Anti-Armour Weapons: Anti-Everything?" (PDF). Asian Military Review. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 7, 2011. Retrieved 2010-05-12.

- ↑ "Same Difference – The 66 is Back". 2009-03-30. Archived from the original on 2011-05-17. Retrieved 2011-08-14.

- ↑ "David Thompkins Interview". GWU. 14 February 1999. Archived from the original on 1 December 2011. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ↑ "Army of the Republic of Vietnam 1955–75". United States. Archived from the original on 30 August 2017. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

External links

| External images | |

|---|---|

| M72 Enhancements Early 1980s | |

- FAS

- Gary's U.S. Infantry Weapons Reference Guide

- Modern Firearms

- Designation-Systems

- Article on the reintroduction of the LAW in Iraq by the USMC

- Canadian Military Page On the M72

- Patent for sights of M72 patented by Paul V. Choate of Milton, MA.

- Patented by Paul V. Choate of Milton, MA.

- 1960s US Army M72 Training film

- FM 3.23-25