Ελλήνες μουσουλμάνοι | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Greek woman in hijab, Turkey, 1710 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Turkish, Greek (Pontic Greek, Cretan Greek, Cypriot Greek, Cappadocian Greek), Georgian, Russian, Arabic | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Greeks, Turkish people |

Greek Muslims, also known as Muslim Rums,[1][2][3][4][5][6] are Muslims of Greek ethnic origin whose adoption of Islam (and often the Turkish language and identity) dates to the period of Ottoman rule in the southern Balkans. They consist primarily of Ottoman-era converts to Islam from Greek Macedonia (e.g., Vallahades), Crete (Cretan Muslims), and northeastern Anatolia (particularly in the regions of Trabzon, Gümüşhane, Sivas, Erzincan, Erzurum, and Kars).

Despite their ethnic Greek origin, the contemporary Greek Muslims of Turkey have been steadily assimilated into the Turkish-speaking Muslim population. Sizable numbers of Greek Muslims, not merely the elders but even young people, have retained knowledge of their respective Greek dialects, such as Cretan and Pontic Greek.[1] Because of their gradual Turkification, as well as the close association of Greece and Greeks with Orthodox Christianity and their perceived status as a historic, military threat to the Turkish Republic, very few are likely to call themselves Greek Muslims. In Greece, Greek-speaking Muslims are not usually considered as forming part of the Greek nation.[7]

In the late Ottoman period, particularly after the Greco-Turkish War (1897), several communities of Greek Muslims from Crete and southern Greece were also relocated to Libya, Lebanon, and Syria, where, in towns like al-Hamidiyah, some of the older generation continue to speak Greek.[8] Historically, Greek Orthodoxy has been associated with being Romios (i.e., Greek) and Islam with being Turkish, despite ethnicity or language.[9]

Most Greek-speaking Muslims in Greece left for Turkey during the 1920s population exchanges under the Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations (in return for Turkish-speaking Christians such as the Karamanlides).[10] Due to the historical role of the millet system, religion and not ethnicity or language was the main factor used during the exchange of populations.[10] All Muslims who departed Greece were seen as "Turks," whereas all Orthodox people leaving Turkey were considered "Greeks," again regardless of their ethnicity or language.[10] An exception was made for the native Muslim Pomaks and Western Thrace Turks living east of the River Nestos in East Macedonia and Thrace, Northern Greece, who are officially recognized as a religious minority by the Greek government.[11]

In Turkey, where most Greek-speaking Muslims live, there are various groups of Greek Muslims, some autochthonous, some from parts of present-day Greece and Cyprus who migrated to Turkey under the population exchanges or immigration.

Motivations for conversion to Islam

The second half of the seventeenth century was a unique moment when the highest officials of the Ottoman state – led by the triumvirate of the sultan, Grand Vizier Fazil Ahmet Pasha and the Valide Sultan Hatice Turhan Sultan – pressured their Christian and Jewish subjects to convert to Islam.

Taxation

Dhimmi were subject to the heavy jizya tax, which was about 20%, versus the Muslim zakat, which was about 3%.[12] Other major taxes were the Defter and İspençe and the more severe Haraç, whereby a document was issued which stated that "the holder of this certificate is able to keep his head on the shoulders since he paid the Haraç tax for this year..." All these taxes were waived if the person converted to Islam.[13][14][15]

Devşirme

Greek non-Muslims were also subjected to practices like Devşirme (blood tax), in which the Ottomans took Christian boys from their families and later converted them to Islam with the aim of selecting and training the ablest of them for leading positions in Ottoman society. Devşirme was not, however, the only means of conversion of Greek Christians. Many male and female orphans voluntarily converted to Islam in order to be adopted or to serve near Turkish families.[16]

Legal system

Another benefit converts received was better legal protection. The Ottoman Empire had two separate court systems, the Islamic court and the non-Islamic court, with the decisions of the former superseding those of the latter. Because non-Muslims were forbidden in the Islamic court, they could not defend their cases and were doomed to lose every time.

Career opportunities

Conversion also yielded greater employment prospects and possibilities of advancement in the Ottoman government bureaucracy and military. Subsequently, these people became part of the Muslim community of the millet system, which was closely linked to Islamic religious rules. At that time, people were bound to their millets by their religious affiliations (or their confessional communities), rather than by their ethnic origins.[17] Muslim communities prospered under the Ottoman Empire, and as Ottoman law did not recognize such notions as ethnicity, Muslims of all ethnic backgrounds enjoyed precisely the same rights and privileges.[18]

Avoiding slavery

During the Greek War of Independence, Ottoman Egyptian troops under the leadership of Ibrahim Pasha of Egypt ravaged the island of Crete and the Greek countryside of the Morea, where Muslim Egyptian soldiers enslaved vast numbers of Christian Greek children and women. Ibrahim arranged for the enslaved Greek children to be forcefully converted to Islam en masse.[19] The enslaved Greeks were subsequently transferred to Egypt, where they were sold. Several decades later in 1843, the English traveler and writer Sir John Gardner Wilkinson described the state of enslaved Greeks who had converted to Islam in Egypt:

White Slaves — In Egypt there are white slaves and slaves of colour. [...] There are [for example] some Greeks who were taken in the War of Independence. [...] In Egypt, the officers of rank are for the most part enfranchised slaves. I have seen in the bazars of Cairo Greek slaves who had been torn from their country, at the time it was about to obtain its liberty; I have seen them afterwards holding nearly all the most important civil and military grades; and one might be almost tempted to think that their servitude was not a misfortune, if one could forget the grief of their parents on seeing them carried off, at a time when they hoped to bequeath to them a religion free from persecution, and a regenerated country.

— [20]

A great many Greeks and Slavs became Muslims to avoid these hardships. Conversion to Islam is quick, and the Ottoman Empire did not keep extensive documentation on the religions of their individual subjects. The only requirements were knowing Turkish, saying you were Muslim, and possibly getting circumcised. Converts might also signal their conversion by wearing the brighter clothes favored by Muslims, rather than the drab garments of Christians and Jews in the empire.[21]

Greek has a specific verb, τουρκεύω (tourkevo), meaning "to become a Turk."[22] The equivalent in Serbian and other South Slavic languages is turčiti (imperfective) or poturčiti (perfective).[23]

Greek Muslims of Pontus and the Caucasus

Geographic dispersal

Pontic Greek (called Ρωμαίικα/Roméika in the Pontus, not Ποντιακά/Pontiaká as it is in Greece), is spoken by large communities of Pontic Greek Muslim origin, spread out near the southern Black Sea coast. Pontian Greek Muslims are found within Trabzon province in the following areas:[24][25]

- In the town of Tonya and in six villages of Tonya district.

- In six villages of the municipal entity of Beşköy in the central and Köprübaşı districts of Sürmene.

- In nine villages of the Galyana valley in Maçka district. These Greek Muslims were resettled there in abandoned former Greek Orthodox Pontian dwellings from the area of Beşköy after a devastating flood in 1929.

- In the Of valley, which contains the largest cluster of Pontian speakers.

- There are 23 Greek Muslim villages in Çaykara district,[26] though due to migration these numbers have fluctuated; according to native speakers of the area, there were around 70 Greek Muslim villages in Çaykara district.[27]

- Twelve Greek Muslim villages are also located in the Dernekpazarı district.[26]

- In other settlements such as Rize (with a large concentration in İkizdere district), Erzincan, Gümüşhane, parts of Erzerum province, and the former Russian Empire's province of Kars Oblast (see Caucasus Greeks) and Georgia (see Islam in Georgia).

Today these Greek-speaking Muslims[28] regard themselves and identify as Turks.[27][29] Nonetheless, a great many have retained knowledge of and/or are fluent in Greek, which continues to be a mother tongue for even young Pontic Muslims.[30] Men are usually bilingual in Turkish and Pontic Greek, while many women are monolingual Pontic Greek speakers.[30]

History

Many Pontic natives were converted to Islam during the first two centuries following the Ottoman conquest of the region. Taking high military and religious posts in the empire, their elite were integrated into the ruling class of imperial society.[31] The converted population accepted Ottoman identity, but in many instances people retained their local, native languages.[31] In 1914, according to the official estimations of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, about 190,000 Greek Muslims were counted in the Pontus alone.[32] Over the years, heavy emigration from the Trabzon region to other parts of Turkey, to places such as Istanbul, Sakarya, Zonguldak, Bursa and Adapazarı, has occurred.[26] Emigration out of Turkey has also occurred, such as to Germany as guest workers during the 1960s.[26]

Glossonyms

In Turkey, Pontic Greek Muslim communities are sometimes called Rum. However, as with Yunan (Turkish for "Greek") or the English word "Greek," this term 'is associated in Turkey to be with Greece and/or Christianity, and many Pontic Greek Muslims refuse such identification.[33][34] The endonym for Pontic Greek is Romeyka, while Rumca and/or Rumcika are Turkish exonyms for all Greek dialects spoken in Turkey.[35] Both are derived from ρωμαίικα, literally "Roman" but referring to the Byzantines.[36] Modern-day Greeks call their language ελληνικά (Hellenika), meaning Greek, an appellation that replaced the previous term Romeiika in the early 19th century.[36] In Turkey, standard modern Greek is called Yunanca; ancient Greek is called either Eski Yunanca or Grekçe.[36]

Religious practice

According to Heath W. Lowry's[37] seminal work on Ottoman tax books[38] (Tahrir Defteri, with co-author Halil İnalcık), most "Turks" in Trebizond and the Pontic Alps region in northeastern Anatolia are of Pontic Greek origin. Pontian Greek Muslims are known in Turkey for their conservative adherence to Sunni Islam of the Hanafi school and are renowned for producing many Quranic teachers.[30] Sufi orders such as Qadiri and Naqshbandi have a great impact.

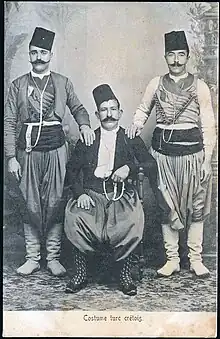

Cretan Muslims

The term Cretan Turks (Turkish: Girit Türkleri, Greek: Τουρκοκρητικοί) or Cretan Muslims (Turkish: Girit Müslümanları) refers to Greek-speaking Muslims[2][39][40] who arrived in Turkey after or slightly before the start of the Greek rule in Crete in 1908, and especially in the context of the 1923 agreement for the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations. Prior to their resettlement in Turkey, deteriorating communal relations between Cretan Greek Christians and Cretan Greek Muslims drove the latter to identify with Ottoman and later Turkish identity.[41]

Geographic dispersal

Cretan Muslims have largely settled on the coastline, stretching from the Çanakkale to İskenderun.[42] Significant numbers were resettled in other Ottoman-controlled areas around the eastern Mediterranean by the Ottomans following the establishment of the autonomous Cretan State in 1898. Most ended up in coastal Syria and Lebanon, particularly the town of Al-Hamidiyah, in Syria, (named after the Ottoman sultan who settled them there), and Tripoli in Lebanon, where many continue to speak Greek as their mother tongue. Others were resettled in Ottoman Tripolitania, especially in the eastern cities like Susa and Benghazi, where they are distinguishable by their Greek surnames. Many of the older members of this last community still speak Cretan Greek in their homes.[42]

A small community of Cretan Greek Muslims still resides in Greece in the Dodecanese islands of Rhodes and Kos.[43] These communities were formed prior to the area becoming part of Greece in 1948, when their ancestors migrated there from Crete, and their members are integrated into the local Muslim population as Turks today.[43]

Language

Some Grecophone Muslims of Crete composed literature for their community in the Greek language, such as songs, but wrote it in the Arabic alphabet.[44] although little of it has been studied.[40]

Today, in various settlements along the Aegean coast, elderly Grecophone Cretan Muslims are still conversant in Cretan Greek.[42] Many in the younger generations are fluent in the Greek language.[45]

Often, members of the Muslim Cretan community are unaware that the language they speak is Greek.[2] Frequently, they refer to their native tongue as Cretan (Kritika Κρητικά or Giritçe) instead of Greek.

Religious practice

Cretan Greek Muslims are Sunnis of the Hanafi school, with a highly influential Bektashi minority who helped shape the folk Islam and religious tolerance of the entire community.

Epirote Greek Muslims

Muslims from the region of Epirus, known collectively as Yanyalılar (singular Yanyalı, meaning "person from Ioannina") in Turkish and Τουρκογιαννιώτες Turkoyanyótes in Greek (singular Τουρκογιαννιώτης Turkoyanyótis, meaning "Turk from Ioannina") arrived in Turkey in two waves of migration, in 1912 and after 1923. After the exchange of populations, Grecophone Epirote Muslims resettled themselves in the Anatolian section of Istanbul, especially the districts from Erenköy to Kartal, which had previously been populated by wealthy Orthodox Greeks.[46] Although the majority of the Epirote Muslim population was of Albanian origins, Grecophone Muslim communities existed in the towns of Souli,[47] Margariti (both majority-Muslim),[48][49] Ioannina, Preveza, Louros, Paramythia, Konitsa, and elsewhere in the Pindus mountain region.[50] The Greek-speaking Muslim[3][44] populations who were a majority in Ioannina and Paramythia, with sizable numbers residing in Parga and possibly Preveza, "shared the same route of identity construction, with no evident differentiation between them and their Albanian-speaking cohabitants."[3][46]

Hoca Sadeddin Efendi, a Greek-speaking Muslim from Ioannina in the 18th century, was the first translator of Aristotle into Turkish.[51] Some Grecophone Muslims of Ioannina composed literature for their community in the Greek language, such as poems, using the Arabic alphabet.[44] The community now is fully integrated into Turkish culture. Last, the Muslims from Epirus that were of mainly Albanian origin are described as Cham Albanians instead.

Macedonian Greek Muslims

The Greek-speaking Muslims[4][7][39][52][53] who lived in the Haliacmon of western Macedonia[54] were known collectively as Vallahades; they had probably converted to Islam en masse in the late 1700s. The Vallahades retained much of their Greek culture and language. This is in contrast with most Greek converts to Islam from Greek Macedonia, other parts of Macedonia, and elsewhere in the southern Balkans, who generally adopted the Turkish language and identity and thoroughly assimilated into the Ottoman ruling elite. According to Todor Simovski's assessment (1972), 13,753 Muslim Greeks lived in Greek Macedonia in 1912.[55]

In the 20th century, the Vallahades were considered by other Greeks to have become Turkish and were not exempt from the 1922–1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey. The Vallahades were resettled in western Asia Minor, in such towns as Kumburgaz, Büyükçekmece, and Çatalca or in villages like Honaz near Denizli.[4] Many Vallahades still continue to speak the Greek language, which they call Romeïka[4] and have become completely assimilated into the Turkish Muslim mainstream as Turks.[56]

Thessalian Greek Muslims

Greek-speaking Muslims lived in Thessaly,[57] mostly centered in and around cities such as Larissa, Trikala, Karditsa, Almyros, and Volos.

Grecophone Muslim communities existed in the towns and certain villages of Elassona, Tyrnovos, and Almyros. According to Lampros Koutsonikas, Muslims in the kaza of Elassona lived in six villages such as Stefanovouno, Lofos, Galanovrysi and Domeniko, as well as the town itself and belonged to the Vallahades group.[58] Evliya Chelebi, who visited the area in 1660s, also mentioned in his Seyahâtnâme that they spoke Greek.[59] In the 8th volume of his Seyahâtnâme he mentions that many Muslims of Thessaly were converts of Greek origin.[60] In particular, he writes that the Muslims of Tyrnovos were converts, and that he could not understand the sect to which the of Muslims of Domokos belonged, claiming they were mixed with "infidels" and thus relieved of paying the haraç tax .[60] Moreover, Chelebi does not mention at all the 12 so-called Konyar Turkish villages that are mentioned in the 18th-century Menâkıbnâme of Turahan Bey, such as Lygaria, Fallani, Itea, Gonnoi, Krokio and Rodia, which were referenced by Ottoman registrars in the yearly books of 1506, 1521. and 1570. This indicates that the Muslims of Thessaly are indeed mostly of convert origin.[61] There were also some Muslims of Vlach descent assimilated into these communities, such as those in the village of Argyropouli. After the Convention of Constantinople in 1881, these Muslims started emigrating to areas that are still under Turkish administration including to the villages of Elassona.[62]

Artillery captain William Martin Leake wrote in his Travels in Northern Greece (1835) that he spoke with the Bektashi Sheikh and the Vezir of Trikala in Greek. In fact, he specifically states that the Sheikh used the word "ἄνθρωπος" to define men, and he quotes the Vezir as saying, καί έγώ εϊμαι προφήτης στά Ιωάννινα..[63] British Consul-General John Elijah Blunt observed in the last quarter of the 19th century, "Greek is also generally spoken by the Turkish inhabitants, and appears to be the common language between Turks and Christians."

Research on purchases of property and goods registered in the notarial archive of Agathagellos Ioannidis between 1882 and 1898, right after the annexation, concludes that the overwhelming majority of Thessalian Muslims who became Greek citizens were able to speak and write Greek. An interpreter was needed only in 15% of transactions, half of which involved women, which might indicate that most Thessalian Muslim women were monolingual and possibly illiterate.[64] However, a sizable population of Circassians and Tatars were settled in Thessaly in the second half of the 19th century, in the towns of Yenişehir (Larissa), Velestino, Ermiye (Almyros), and villages of Balabanlı (Asimochori) and Loksada in Karditsa.[65] It is possible that they and also the Albanian Muslims were the ones who did not fully understand the Greek Language. Moreover, some Muslims served as interpreters in these transactions.

Greek Morean/Peleponnesian Muslims

Greek-speaking Muslims lived in cities, citadels, towns, and some villages close to fortified settlements in the Peleponnese, such as Patras, Rio, Tripolitsa, Koroni, Navarino, and Methoni. Evliya Chelebi has also mentioned in his Seyahatnâme that the language of all Muslims in Morea was Urumşa, which is demotic Greek. In particular, he mentions that the wives of Muslims in the castle of Gördüs were non-Muslims. He says that the peoples of Gastouni speak Urumşa, but that they were devout and friendly nonetheless. He explicitly states that the Muslims of Longanikos were converted Greeks, or ahıryan.[59]

Greek Cypriot Muslims

In 1878 the Muslim inhabitants of Cyprus constituted about one-third of the island's population of 120,000. They were classified as being either Turkish or "neo-Muslim." The latter were of Greek origin, Islamised but speaking Greek, and similar in character to the local Christians. The last of such groups was reported to arrive at Antalya in 1936. These communities are thought to have abandoned Greek in the course of integration.[66] During the 1950s, there were still four Greek speaking Muslim settlements in Cyprus: Lapithiou, Platanissos, Ayios Simeon and Galinoporni that identified themselves as Turks.[5] A 2017 study on the genetics of Turkish Cypriots has shown strong genetic ties with their fellow Orthodox Greek Cypriots.[67][68]

Greek Muslims of the Aegean Islands

Despite not having a majority Muslim population at any time during the Ottoman period,[69] some Aegean Islands such as Chios, Lesbos, Kos, Rhodes, Lemnos and Tenedos, and on Kastellorizo contained a sizable Muslim population of Greek origin.[70] Before the Greek Revolution, there were also Muslims on the island of Euboea, but there were no Muslims in the Cyclades and Sporades island groups. Evliya Chelebi mentions that there were 100 Muslim houses on the island of Aegina in 1660s.[60] On most islands, Muslims were only living in and around the main centers of the islands. Today, about 5,000–5,500 Greek-speaking Muslims (called Turks of the Dodecanese) live on Kos and Rhodes. This is because the Dodecanese islands were governed by Italy during the Greek-Turkish population exchange, and so these populations were exempt. However, many migrated after the Paris Peace Treaties in 1947.

Crimea

In the Middle Ages the Greek population of Crimea traditionally adhered to Eastern Orthodox Christianity, even despite undergoing linguistic assimilation by the local Crimean Tatars. In 1777–1778, when Catherine the Great of Russia conquered the peninsula from the Ottoman Empire, the local Orthodox population was forcibly deported and settled north of the Azov Sea. In order to avoid deportation, some Greeks chose to convert to Islam. Crimean Tatar-speaking Muslims of the village of Kermenchik (renamed to Vysokoye in 1945) kept their Greek identity and were practicing Christianity in secret for a while. In the nineteenth century the lower half of Kermenchik was populated with Christian Greeks from Turkey, whereas the upper remained Muslim. By the time of the 1944 deportation, the Muslims of Kermenchik had already been identified as Crimean Tatars, and were forcibly expelled to Central Asia together with the rest of Crimea's ethnic minorities.[71]

Lebanon and Syria

There are about 7,000 Greek-speaking Muslims living in Tripoli, Lebanon and about 8,000 in Al Hamidiyah, Syria.[72] The majority of them are Muslims of Cretan origin. Records suggest that the community left Crete between 1866 and 1897, on the outbreak of the last Cretan uprising against the Ottoman Empire, which ended the Greco-Turkish War of 1897.[72] Sultan Abdul Hamid II provided Cretan Muslim families who fled the island with refuge on the Levantine coast. The new settlement was named Hamidiye after the sultan.

Many Grecophone Muslims of Lebanon somewhat managed to preserve their Cretan Muslim identity and Greek language[73] Unlike neighbouring communities, they are monogamous and consider divorce a disgrace. Until the Lebanese Civil War, their community was close-knit and entirely endogamous. However many of them left Lebanon during the 15 years of the war.[72]

Greek-speaking Muslims[6] constitute 60% of Al Hamidiyah's population. The percentage may be higher but is not conclusive because of hybrid relationship in families. The community is very much concerned with maintaining its culture. The knowledge of the spoken Greek language is remarkably good and their contact with their historical homeland has been possible by means of satellite television and relatives. They are also known to be monogamous.[72] Today, Grecophone Hamidiyah residents identify themselves as Cretan Muslims, while some others as Cretan Turks.[74]

By 1988, many Grecophone Muslims from both Lebanon and Syria had reported being subject to discrimination by the Greek embassy because of their religious affiliation. The community members would be regarded with indifference and even hostility, and would be denied visas and opportunities to improve their Greek through trips to Greece.[72]

Central Asia

In the Middle Ages, after the Seljuq victory over the Byzantine Emperor Romanus IV, many Byzantine Greeks were taken as slaves to Central Asia. The most famous among them was Al-Khazini, a Byzantine Greek slave taken to Merv, then in the Khorasan province of Persia but now in Turkmenistan, who was later freed and became a famous Muslim scientist.[75]

Other Greek Muslims

- Cappadocian Greek-speaking Muslims, Cappadocia

- Greek-speaking Anatolian Muslims

- Greek-speaking Muslims of Thrace

- Greek-speaking Muslims of North Africa

Muslims of partial Greek descent (non-conversions)

- Abu Firas al-Hamdani, Al-Harith ibn Abi’l-ʿAlaʾ Saʿid ibn Hamdan al-Taghlibi (932–968), better known by his nom de plume of Abu Firas al-Hamdani (Arabic: أبو فراس الحمداني), was an Arab prince and poet. He was a cousin of Sayf al-Dawla and a member of the noble family of the Hamdanids, who were rulers in northern Syria and Upper Mesopotamia during the 10th century. He served Sayf al-Dawla as governor of Manbij as well as court poet, and was active in his cousin's wars against the Byzantine Empire. He was captured by the Byzantines in 959/962 and spent four or seven years at their capital, Constantinople, where he composed his most famous work, the collection of poems titled al-Rūmiyyāt (الروميات). His father Abi'l-Ala Sa'id—a son of the Hamdanid family's founder, Hamdan ibn Hamdun — occupied a distinguished position in the court of the Abbasid caliph al-Muqtadir (reigned 908–932). Abu Firas' mother was a Byzantine Greek slave concubine (an umm walad, freed after giving birth to her master's child). His maternal descent later was a source of scorn and taunts from his Hamdanid relatives, a fact reflected in his poems.

- Abu Ubaid al-Qasim bin Salam al-Khurasani al-Harawi (Arabic: أبو عبيد القاسم بن سلاّم الخراساني الهروي; c. 770–838) was an Arab philologist and the author of many standard works on lexicography, Qur’anic sciences, hadith, and fiqh. He was born in Herat, the son of a Byzantine/Greek slave. He left his native town and studied philology in Basra under many famous scholars such as al-Asmaʿi (d. 213/828), Abu ʿUbayda (d. c.210/825), and Abu Zayd al-Ansari (d. 214 or 215/830–1), and in Kufa under, among others, Abu ʿAmr al-Shaybani (d. c.210/825), al-Kisaʾi (d. c.189/805) and others.

- Süleyman Pasha (died 1357), son of Orhan, Ottoman sultan, and Nilüfer Hatun.[76]

- Ahmed I - (1590-1617), Ottoman sultan, Greek mother (Gülnus Sultan) - wife of Ottoman sultan Mehmed III.

- Ahmed III – (1673–1736), Ottoman sultan, Greek mother (Emetullah Rabia Gülnûş Sultan), originally named Evemia, who was the daughter of a Greek Cretan priest.

- Al-Muhtadi – Abū Isḥāq Muḥammad ibn al-Wāṯiq (died 21 June 870), better known by his regnal name al-Muhtadī bi-'llāh (Arabic: المهتدي بالله, "Guided by God"), was the Caliph of the Abbasid Caliphate from July 869 to June 870, during the "Anarchy at Samarra". Al-Muhtadi's mother was Qurb, a Greek slave. As a ruler, al-Muhtadi sought to emulate the Umayyad caliph Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz, widely considered a model Islamic ruler. He therefore lived an austere and pious life—notably removing all musical instruments from the court—and made a point of presiding in person over the courts of grievances (mazalim), thus gaining the support of the common people. Combining "strength and ability", he was determined to restore the Caliph's authority and power, that had been eroded during the ongoing "Anarchy at Samarra" by the squabbles of the Turkish generals.

- Al-Mu'tadid, Abu'l-Abbas Ahmad ibn Talha al-Muwaffaq (Arabic: أبو العباس أحمد بن طلحة الموفق, translit. ʿAbū al-ʿAbbās Aḥmad ibn Ṭalḥa al-Muwaffaq; 854 or 861 – 5 April 902), better known by his regnal name al-Mu'tadid bi-llah (Arabic: المعتضد بالله, "Seeking Support in God") was the Caliph of the Abbasid Caliphate from 892 until his death in 902. Al-Mu'tadid was born Ahmad, the son of Talha, one of the sons of the Abbasid caliph al-Mutawakkil (r. 847–861), and a Greek slave named Dirar.

- Al-Wathiq – Abū Jaʿfar Hārūn ibn Muḥammad (Arabic: أبو جعفر هارون بن محمد المعتصم; 18 April 812 – 10 August 847), better known by his regnal name al-Wāthiq Bi’llāh (الواثق بالله, "He who trusts in God"), was an Abbasid caliph who reigned from 842 until 847 AD (227–232 AH in the Islamic calendar). Al-Wathiq was the son of al-Mu'tasim by a Byzantine Greek slave (umm walad), Qaratis. He was named Harun after his grandfather, Caliph Harun al-Rashid (r. 786–809).

- Bayezid I – (1354–1403), Ottoman sultan, Greek mother (Gulcicek Hatun or Gülçiçek Hatun) wife of Murad I.

- Bayezid II – (1447–1512), Ottoman sultan. The more widespread view is that his mother was of Albanian origin,[77][78][79] though a Greek origin has also been proposed.[80]

- Hasan Pasha (son of Barbarossa) (c. 1517–1572) was the son of Hayreddin Barbarossa (whose mother Katerina was Greek) and three-times Beylerbey of Algiers, Algeria. He succeeded his father as ruler of Algiers, and replaced Barbarossa's deputy Hasan Agha who had been effectively holding the position of ruler of Algiers since 1533.

- Hayreddin Barbarossa, (c. 1478–1546), privateer and Ottoman admiral, whose mother Katerina, was a Greek from Mytilene on the island of Lesbos.

- Hussein Kamel of Egypt, Sultan Hussein Kamel (Arabic: السلطان حسين كامل, Turkish: Sultan Hüseyin Kamil Paşa; November 1853 – 9 October 1917) was the Sultan of Egypt from 19 December 1914 to 9 October 1917, during the British protectorate over Egypt. Hussein Kamel was the second son of Khedive Isma'il Pasha, who ruled Egypt from 1863 to 1879 and his Greek wife Nur Felek Kadin.

- Ibrahim I, (1615–1648), Ottoman sultan, Greek mother (Mahpeyker Kösem Sultan), the daughter of a priest from the island of Tinos; her maiden name was Anastasia and was one of the most powerful women in Ottoman history.

- Ibn al-Rumi – Arab poet was the son of a Persian mother and a Byzantine freedman father and convert to Islam.

- Kaykaus II, Seljuq Sultan. His mother was the daughter of a Greek priest; and it was the Greeks of Nicaea from whom he consistently sought aid throughout his life.

- Kaykhusraw II, Ghiyath al-Din Kaykhusraw II or Ghiyāth ad-Dīn Kaykhusraw bin Kayqubād (Persian: غياث الدين كيخسرو بن كيقباد) was the sultan of the Seljuqs of Rûm from 1237 until his death in 1246. He ruled at the time of the Babai uprising and the Mongol invasion of Anatolia. He led the Seljuq army with its Christian allies at the Battle of Köse Dağ in 1243. He was the last of the Seljuq sultans to wield any significant power and died as a vassal of the Mongols. Kaykhusraw was the son of Kayqubad I and his wife Mah Pari Khatun, who was Greek by origin.

- Mahmoud Sami el-Baroudi, (1839–1904) was Prime Minister of Egypt from 4 February 1882 until 26 May 1882 and a prominent poet. He was known as Rab Alseif Wel Qalam رب السيف و القلم ("lord of sword and pen"). His father belonged to an Ottoman-Egyptian family while his mother was a Greek woman who converted to Islam upon marrying his father.[81][82]

- Mongi Slim (Arabic: منجي سليم, Turkish: Mengi Selim) (September 1, 1908 – October 23, 1969) was a Tunisian diplomat who became the first African to become the President of the United Nations General Assembly in 1961. He received a degree from the faculty of law of the University of Paris. He was twice imprisoned by the French during the Tunisian struggle for independence. Slim came from an aristocratic family of Greek and Turkish origin. One of Slim's great-grandfathers, a Greek named Kafkalas, was captured as a boy by pirates, and sold to the Bey of Tunis, who educated and freed him and then made him his minister of defence.

- Murad I, (1360–1389) Ottoman sultan, Greek mother, (Nilüfer Hatun (water lily in Turkish), daughter of the Prince of Yarhisar or Byzantine Princess Helen (Nilüfer).

- Murad IV (1612–1640), Ottoman sultan, Greek mother (Valide Sultan, Kadinefendi Kösem Sultan or Mahpeyker, originally named Anastasia)

- Mustafa II – (1664–1703),[83][84][85][86] Ottoman sultan, Greek Cretan mother (Valide Sultan, Mah-Para Ummatullah Rabia Gül-Nush, originally named Evemia).

- Oruç Reis, (also called Barbarossa or Redbeard), privateer and Ottoman Bey (Governor) of Algiers and Beylerbey (Chief Governor) of the West Mediterranean. He was born on the island of Midilli (Lesbos), mother was Greek (Katerina).

- Osman Hamdi Bey – (1842 – 24 February 1910), Ottoman statesman and art expert and also a prominent and pioneering painter, the son of İbrahim Edhem Pasha,[87] a Greek[88] by birth abducted as a youth following the Massacre of Chios. He was the founder of the Archaeological Museum of Istanbul.[88]

- Selim I, Ottoman sultan; there is a proposed Greek origin for his father, Bayezid II, through his mother's side (Valide Sultan Amina Gul-Bahar or Gulbahar Khatun – a Greek convert to Islam); and for his mother Gülbahar Hatun (wife of Bayezid II), which would make him three-quarters Greek if both are valid.[89]

- Şehzade Halil (probably 1346–1362) was an Ottoman prince. His father was Orhan, the second bey of the Ottoman beylik (later empire). His mother was Theodora Kantakouzene, the daughter of Byzantine emperor John VI Kantakouzenos and Irene Asanina. His kidnapping was an important event in 14th century Ottoman-Byzantine relations.

- Taleedah Tamer is a Saudi Arabian fashion model. She is the first Saudi model to walk a couture runway in Paris and the first to be on the cover of an international magazine. Taleedah Tamer was born and raised in Jeddah, Makkah in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Her father, Ayman Tamer, is a Saudi businessman who is CEO and chairman of Tamer Group, a pharmaceutical, healthcare, and beauty company. Her mother, Cristina Tamer, is an Italian former dancer and model for Giorgio Armani, Gianfranco Ferré and La Perla. Her grandmother is Greek.[90]

- Sheikh Bedreddin – (1359–1420) Revolutionary theologian, Greek mother named "Melek Hatun".

- Tevfik Fikret (1867–1915) an Ottoman poet who is considered the founder of the modern school of Turkish poetry, his mother was a Greek convert to Islam from the island of Chios.[91][92]

Muslims of Greek descent (non-conversions)

- Hussein Hilmi Pasha – (1855–1922), Ottoman statesman born on Lesbos to a family of Greek ancestry[93][94][95][96] who had formerly converted to Islam.[97] He became twice Grand vizier[98] of the Ottoman Empire in the wake of the Second Constitutional Era and was also co-founder and Head of the Turkish Red Crescent.[99] Hüseyin Hilmi was one of the most successful Ottoman administrators in the Balkans of the early 20th century becoming Ottoman Inspector-General of Macedonia[100] from 1902 to 1908, Ottoman Minister for the Interior[101] from 1908 to 1909 and Ottoman Ambassador at Vienna[102] from 1912 to 1918.

- Hadji Mustafa Pasha (1733-1801), of Greek Muslim origin, Ottoman commander.[103]

- Ahmet Vefik Paşa (Istanbul, 3 July 1823 – 2 April 1891), was a famous Ottoman of Greek descent[104][105][106][107][108][109][110] (whose ancestors had converted to Islam).[104] He was a statesman, diplomat, playwright and translator of the Tanzimat period. He was commissioned with top-rank governmental duties, including presiding over the first Turkish parliament.[111] He also became a grand vizier for two brief periods. Vefik also established the first Ottoman theatre[112] and initiated the first Western style theatre plays in Bursa and translated Molière's major works.

- Ahmed Resmî Efendi (English, "Ahmed Efendi of Resmo") (1700–1783) also called Ahmed bin İbrahim Giridî ("Ahmed the son of İbrahim the Cretan") was a Grecophone Ottoman statesman, diplomat and historian, who was born into a Muslim family of Greek descent in the Cretan town of Rethymno.[113][114][115][116] In international relations terms, his most important – and unfortunate – task was to act as the chief of the Ottoman delegation during the negotiations and the signature of the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca. In the literary domain, he is remembered for various works among which his sefâretnâme recounting his embassies in Berlin and Vienna occupy a prominent place. He was Turkey's first ever ambassador in Berlin.

- Adnan Kahveci (1949–1993) was a noted Turkish politician who served as a key advisor to Prime Minister Turgut Özal throughout the 1980s. His family came from the region of Pontus and Kahveci was a fluent Greek speaker.[117]

- Bülent Arınç (born. 25 May 1948) is a Deputy Prime Minister of Turkey since 2009. He is of Grecophone Cretan Muslim heritage with his ancestors arriving to Turkey as Cretan refugees during the time of Sultan Abdul Hamid II[118] and is fluent in Cretan Greek.[119] Arınç is a proponent of wanting to reconvert the Hagia Sophia into a mosque, which has caused diplomatic protestations from Greece.[120]

Greek converts to Islam

- Al-Khazini – (flourished 1115–1130) was a Greek Muslim scientist, astronomer, physicist, biologist, alchemist, mathematician and philosopher – lived in Merv (modern-day Turkmenistan)

- Atik Sinan or "Old Sinan" – Ottoman architect (not to be confused with the other Sinan whose origins are disputed between Greek, Albanian, Turk or Armenian (see below))

- Badr al-Hammami, Badr ibn ʿAbdallāh al-Ḥammāmī, also known as Badr al-Kabīr ("Badr the Elder"),[1] was a general who served the Tulunids and later the Abbasids. Of Greek origin, Badr was originally a slave of the founder of the Tulunid autonomous regime, Ahmad ibn Tulun, who later set him free. In 914, he was the Abbasid governor of Fars.

- Carlos Mavroleon – son of a Greek ship-owner, Etonian heir to a £100m fortune, close to the Kennedys and almost married a Heseltine, former Wall Street broker and a war correspondent, leader of an Afghan Mujahideen unit during the Afghan war against the Soviets – died under mysterious circumstances in Peshawar, Pakistan

- Damat Hasan Pasha, Ottoman Grand Vizier between 1703 and 1704.[123] He was originally a Greek convert to Islam from the Morea.[124][125]

- Damian of Tarsus – Damian (died 924), known in Arabic as Damyanah and surnamed Ghulam Yazman ("slave/page of Yazman"), was a Byzantine Greek convert to Islam, governor of Tarsus in 896–897 and one of the main leaders of naval raids against the Byzantine Empire in the early 10th century. In 911, he attacked Cyprus, which since the 7th century had been a neutralized Arab-Byzantine condominium, and ravaged it for four months because its inhabitants had assisted a Byzantine fleet under admiral Himerios in attacking the Caliphate's coasts the year before.

- Diam's (Mélanie Georgiades) French rapper of Greek origin.

- Dhuka al-Rumi ("Doukas the Roman") (died 11 August 919) was a Byzantine Greek who served the Abbasid Caliphate, most notably as governor of Egypt in 915–919. He was installed as governor of Egypt in 915 by the Abbasid commander-in-chief Mu'nis al-Muzaffar, as part of his effort to stabilize the situation in the country and expel a Fatimid invasion that had taken Alexandria.

- Emetullah Rabia Gülnûş Sultan (1642–1715) was the wife of Ottoman Sultan Mehmed IV and Valide Sultan to their sons Mustafa II and Ahmed III (1695–1715). She was born to a priest in Rethymno, Crete, then under Venetian rule, her maiden name was Evmania Voria and she was an ethnic Greek.[84][126][127][128][129][130][131][132][133][134] She was captured when the Ottomans conquered Rethymno about 1646 and she was sent as slave to Constantinople, where she was given Turkish and Muslim education in the harem department of Topkapı Palace and soon attracted the attention of the Sultan, Mehmed IV.

- Gawhar al-Siqilli,[135][136][137][138] (born c. 928–930, died 992), of Greek descent originally from Sicily, who had risen to the ranks of the commander of the Fatimid armies. He had led the conquest of North Africa[139] and then of Egypt and founded the city of Cairo[140] and the great al-Azhar mosque.

- Gazi Evrenos - (d. 1417), an Ottoman military commander serving as general under Süleyman Pasha, Murad I, Bayezid I, Süleyman Çelebi and Mehmed I

- Hamza Tzortzis – Hamza Andreas Tzortzis is a British public speaker and researcher on Islam. A British Muslim convert of Greek heritage. In 2015 he was a finalist for Religious Advocate of the Year at the British Muslim Awards. Tzortzis has contributed to the BBC news programs: The Big Questions and Newsnight.

- Hamza Yusuf – American Islamic teacher and lecturer.

- Handan Sultan, wife of Ottoman Sultan Mehmed III

- Hass Murad Pasha was an Ottoman statesman and commander of Byzantine Greek origin. According to the 16th-century Ecthesis Chronica, Hass Murad and his brother, Mesih Pasha, were sons of a certain Gidos Palaiologos, identified by the contemporary Historia Turchesca as a brother of a Byzantine Emperor. This is commonly held to have been Constantine XI Palaiologos, the last Byzantine emperor, who fell during the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II in 1453. If true, since Constantine XI died childless, and if the Ottomans had failed to conquer Constantinople, Mesih or Hass Murad might have succeeded him. The brothers were captured during the fall of Constantinople, converted to Islam, and raised as pages under the auspices of Sultan Mehmed II as part of the devşirme system.

- İbrahim Edhem Pasha, born of Greek ancestry[87][121][141][142][143] on the island of Chios, Ottoman statesman who held the office of Grand Vizier in the beginning of Abdulhamid II's reign between 5 February 1877 and 11 January 1878

- İshak Pasha (? – 1497, Thessaloniki) was a Greek (though some reports say he was Croatian) who became an Ottoman general, statesman and later Grand Vizier. His first term as a Grand Vizier was during the reign of Mehmet II ("The Conqueror"). During this term he transferred Turkmen people from their Anatolian city of Aksaray to newly conquered İstanbul to populate the city which had lost a portion of its former population prior to conquest. The quarter of the city is where the Aksaray migrants had settled is now called Aksaray. His second term was during the reign of Beyazıt II.

- Ismail Selim Pasha (Greek: Ισμαήλ Σελίμ Πασάς, ca. 1809–1867), also known as Ismail Ferik Pasha, was an Egyptian general of Greek origin. He was a grandson of Alexios Alexis (1692–1786) and a great-grandson of the nobleman Misser Alexis (1637 – ?). Ismail Selim was born Emmanouil (Greek: Εμμανουήλ Παπαδάκης) c. 1809 in a village near Psychro, located at the Lasithi Plateau on the island of Crete. He had been placed in the household of the priest Fragios Papadakis (Greek: Φραγκιός Παπαδάκης) when Fragios was slaughtered in 1823 by the Ottomans during the Greek War of Independence. Emmanouil's natural father was the Reverend Nicholas Alexios Alexis who died in the epidemic of plague in 1818. Emmanouil and his younger brothers Antonios Papadakis (Greek: Αντώνιος Παπαδάκης (1810–1878) and Andreas were captured by the Ottoman forces under Hassan Pasha who seized the plateau and were sold as slaves.

- Jamilah Kolocotronis, Greek-German ex. Lutheran scholar and writer.

- John Tzelepes Komnenos – (Greek: Ἰωάννης Κομνηνὸς Τζελέπης) son of Isaac Komnenos (d. 1154). Starting about 1130 John and his father, who was a brother of Emperor John II Komnenos ("John the Beautiful"), plotted to overthrow his uncle the emperor. They made various plans and alliances with the Danishmend leader and other Turks who held parts of Asia Minor. In 1138 John and his father had a reconciliation with the Emperor, and received a full pardon. In 1139 John accompanied the emperor on his campaign in Asia Minor. In 1140 at the siege of Neocaesarea he defected. As John Julius Norwich puts it, he did so by "embracing simultaneously the creed of Islam and the daughter of the Seljuk Sultan Mesud I." John Komnenos' by-name, Tzelepes, is believed to be a Greek rendering of the Turkish honorific Çelebi, a term indicating noble birth or "gentlemanly conduct". The Ottoman Sultans claimed descent from John Komnenos.

- Köse Mihal (Turkish for "Michael the Beardless"; 13th century – c. 1340) accompanied Osman I in his ascent to power as an Emir and founder of the Ottoman Empire. He is considered to be the first significant Byzantine renegade and convert to Islam to enter Ottoman service. He was also known as 'Gazi Mihal' and 'Abdullah Mihal Gazi'. Köse Mihal, was the Byzantine governor of Chirmenkia (Harmankaya, today Harmanköy) and was ethnically Greek. His original name was "Michael Cosses". The castle of Harmankaya (also known as Belekoma Castle) was in the foothills of the Uludağ Mountains in Bilecik Turkey. Mihal also eventually gained control of Lefke, Meceke and Akhisar.

- Kösem Sultan – (1581–1651) also known as Mehpeyker Sultan was the most powerful woman in Ottoman history, consort and favourite concubine of Ottoman Sultan Ahmed I (r. 1603–1617), she became Valide Sultan from 1623 to 1651, when her sons Murad IV and Ibrahim I and her grandson Mehmed IV (1648–1687) reigned as Ottoman sultans; she was the daughter of a priest from the island of Tinos – her maiden name was Anastasia

- Leo of Tripoli (Greek: Λέων ὸ Τριπολίτης) was a Greek renegade and pirate serving Arab interests in the early tenth century.

- Mahfiruze Hatice Sultan – (d 1621), maiden name Maria, was the wife of the Ottoman Sultan Ahmed I and mother of Osman II.

- Mahmud Pasha Angelović – Mahmud Pasha or Mahmud-paša Anđelović (1420–1474), also known simply as Adni, was Serbian-born, of Byzantine noble descent (Angeloi) who became an Ottoman general and statesman, after being abducted as a child by the Sultan. As Veli Mahmud Paşa he was Grand Vizier in 1456–1468 and again in 1472–1474. A capable military commander, throughout his tenure he led armies or accompanied Mehmed II on his own campaigns.

- Mesih Pasha (Mesih Paşa or Misac Pasha) (died November 1501) was an Ottoman statesman of Byzantine Greek origin, being a nephew of the last Byzantine emperor, Constantine XI Palaiologos. He served as Kapudan Pasha of the Ottoman Navy and was grand vizier of the Ottoman Empire from 1499 to 1501. Mesih and his elder brother, Khass Murad, were captured during the fall of Constantinople and raised as pages under the auspices of Mehmed II. Mesih was approximately ten years old at the time he was taken into palace service. He and two of his brothers, one of whom was Hass Murad Pasha, were captured, converted to Islam, and raised as pages under the auspices of Mehmed II as part of the devşirme system.

- Mimar Sinan (1489–1588) – Ottoman architect – his origins are possibly Greek. There is not a single document in Ottoman archives which state whether Sinan was Armenian, Albanian, Turk or Greek, only "Orthodox Christian". Those who suggest that he could be Armenian do this with the mere fact that the largest Christian community living at the vicinity of Kayseri were Armenians, but there was also a considerably large Greek population (e.g. the father of Greek-American film director Elia Kazan) in Kayseri.

- Mehmed Saqizli (Turkish: Sakızlı Mehmed Paşa, literally, Mehmed Pasha of Chios) (died 1649), (r.1631–49) was Dey and Pasha of Tripolis. He was born into a Christian family of Greek origin on the island of Chios and had converted to Islam after living in Algeria for years.[144]

- Misac Palaeologos Pasha, a member of the Byzantine Palaiologos dynasty and the Ottoman commander in the first Siege of Rhodes (1480). He was an Ottoman statesman and Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire from 1499 to 1501.

- Mohammed Khaznadar (محمد خزندار), born c. 1810 on the island of Kos (modern Greece) and died on 1889 at La Marsa was a Tunisian politician. A Mameluke of Greek origin, he was captured in a raid and bought as a slave by the Bey of Tunis: Hussein II Bey. Later on he became treasurer to Chakir Saheb Ettabaâ and was qaid of Sousse and Monastir from 1838. He remained for fifty years in one post or another in the service of five successive beys. In November 1861 he was named Minister of the Interior, then Minister of War in December 1862, Minister of the Navy in September 1865, Minister of the Interior again in October 1873 and finally Grand Vizier and President of the International Financial Commission from 22 July 1877 to 24 August 1878.

- Mustapha Khaznadar (1817-1887)(مصطفى خزندار), was Prime Minister of the Beylik of Tunis[145] from 1837 to 1873. Of Greek origin,[146][122][147][148][149] as Georgios Kalkias Stravelakis[149][150][151] he was born on the island of Chios in 1817.[150] Along with his brother Yannis, he was captured and sold into slavery[152] by the Ottomans during the Massacre of Chios in 1822, while his father Stephanis Kalkias Stravelakis was killed. He was then taken to Smyrna and then Constantinople, where he was sold as a slave to an envoy of the Bey of Tunis.

- Narjis, mother of Muhammad al-Mahdi the twelfth and last Imam of Shi'a Islam, Byzantine Princess, reportedly the descendant of the disciple Simon Peter, the vicegerent of Jesus.

- Nilüfer Hatun (Ottoman Turkish: نیلوفر خاتون, birth name Holifere (Holophira) / Olivera, other names Bayalun, Beylun, Beyalun, Bilun, Suyun, Suylun) was a Valide Hatun; the wife of Orhan, the second Ottoman Sultan. She was mother of the next sultan, Murad I. The traditional stories about her origin, traced back to the 15th century, are that she was daughter of the Byzantine ruler (Tekfur) of Bilecik, called Holofira. As some stories go, Orhan's father Osman raided Bilecik at the time of Holofira's wedding arriving there with rich presents and disguised and hidden soldiers. Holofira was among the loot and given to Orhan. However modern researchers doubt this story, admitting that it may have been based on real events. Doubts are based on various secondary evidence and lack of direct documentary evidence of the time. In particular, her Ottoman name Nilüfer meaning water lily in the Persian language. Other Historians make her a daughter of the Prince of Yarhisar or a Byzantine Princess Helen (Nilüfer), who was of ethnic Greek descent. Nilüfer Hatun Imareti (Turkish for "Nilüfer Hatun Soup Kitchen"), is a convent annex hospice for dervishes, now housing the Iznik Museum in İznik, Bursa Province. When Orhan Gazi was off on campaign Nilüfer acted as his regent, the only woman in Ottoman history who was ever given such power. During Murad's reign she was recognized as Valide Sultan, or Queen Mother, the first in Ottoman history to hold this title, and when she died she was buried beside Orhan Gazi and his father Osman Gazi in Bursa. The Muslim traveler Ibn Battuta, who visited Iznik in the 1330s, was a guest of Nilüfer Hatun, whom he described as 'a pious and excellent woman'.

- Nur Felek Kadinefendi (1863–1914), was the first consort of Isma'il Pasha of Egypt. She was born in Greece in 1837. Her maiden name was Tatiana. At a young age, she was captured during one the raids and sold into slavery. She was delivered as a concubine to the harem of Sa'id ,the Wāli of Egypt in 1852. However, Isma'il Pasha, then not yet the Khedive of Egypt, took Tatiana as a concubine for him. She gave birth to Prince Hussein Kamel Pasha in 1853. She later converted to Islam and her name was changed to Nur Felek. When Isma'il Pasha ascended the throne in 1863, she was elevated to the rank of first Kadinefendi, literally meaning first consort, or wife.

- Osman Saqizli (Turkish: Sakızlı Osman Paşa, literally, Osman Pasha of Chios) (died 1672), (r.1649–72) was Dey and Pasha of Tripoli in Ottoman Libya. He was born into a Greek Christian family on the island of Chios (known in Ottoman Turkish as Sakız, hence his epithet "Sakızlı") and had converted to Islam.[144]

- Pargalı İbrahim Pasha (d. 1536), the first Grand Vizier appointed by Suleiman the Magnificent of the Ottoman Empire (reigned 1520 to 1566).

- Photios (Emirate of Crete) – Photios (Greek: Φώτιος, fl. ca. 872/3) was a Byzantine renegade and convert to Islam who served the Emirate of Crete as a naval commander in the 870s.

- Raghib Pasha (1819–1884), was Prime Minister of Egypt.[153] He was of Greek ancestry[154][155][156][157] and was born in Greece[158] on 18 August 1819 on either the island of Chios following the great Massacre[159] or Candia[160] Crete. After being kidnapped to Anatolia he was brought to Egypt as a slave by Ibrahim Pasha in 1830[161] and converted to Islam. Raghib Pasha ultimately rose to levels of importance serving as Minister of Finance (1858–1860), then Minister of War (1860–1861). He became Inspector for the Maritime Provinces in 1862, and later Assistant (Arabic: باشمعاون) to viceroy Isma'il Pasha (1863–1865). He was granted the title of beylerbey and then appointed President of the Privy council in 1868. He was appointed President of the Chamber of Deputies (1866–1867), then Minister of Interior in 1867, then Minister of Agriculture and Trade in 1875. Isma'il Ragheb became Prime Minister of Egypt in 1882.\

- Reşid Mehmed Pasha, also known as Kütahı (Greek: Μεχμέτ Ρεσίτ πασάς Κιουταχής, 1780–1836), was a prominent Ottoman statesman and general who reached the post of Grand Vizier in the first half of the 19th century, playing an important role in the Greek War of Independence. Reşid Mehmed was born in Georgia, the son of a Greek Orthodox priest. As a child, he was captured as a slave by the Turks, and brought to the service of the then Kapudan Pasha Husrev Pasha. His intelligence and ability impressed his master, and secured his rapid rise.

- Rum Mehmed Pasha was an Ottoman statesman. He was Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire from 1466 to 1469.

- Saliha Sultan (Ottoman Turkish: صالحه سلطان; c. 1680 – 21 September 1739) was the consort of Sultan Mustafa II of the Ottoman Empire, and Valide sultan to their son, Sultan Mahmud I. Saliha Sultan was allegedly born in 1680 in a Greek family in Azapkapı, Istanbul.

- Turgut Reis – (1485–1565) was a notorious Barbary pirate of the Ottoman Empire. He was born of Greek descent[162][163][164][165][166][167] in a village near Bodrum, on the Aegean coast of Asia Minor. After converting to Islam in his youth[166] he served as Admiral and privateer who also served as Bey of Algiers; Beylerbey of the Mediterranean; and first Bey, later Pasha, of Tripoli. Under his naval command the Ottoman Empire was extended across North Africa.[168] When Tugut was serving as pasha of Tripoli, he adorned and built up the city, making it one of the most impressive cities along the North African Coast.[169] He was killed in action in the Great Siege of Malta.[170]

- Yaqut al-Hamawi (Yaqut ibn-'Abdullah al-Rumi al-Hamawi) (1179–1229) (Arabic: ياقوت الحموي الرومي) was an Islamic biographer and geographer renowned for his encyclopaedic writings on the Muslim world. He was born in Constantinople, and as his nisba "al-Rumi" ("from Rūm") indicates he had Byzantine Greek ancestry.

- Yaqut al-Musta'simi (also Yakut-i Musta'simi) (died 1298) was a well-known calligrapher and secretary of the last Abbasid caliph. He was born of Greek origin in Amaseia and carried off when he was very young. He codified six basic calligraphic styles of the Arabic script. Naskh script was said to have been revealed and taught to the scribe in a vision. He developed Yakuti, a handwriting named after him, described as a thuluth of "a particularly elegant and beautiful type." Supposedly he had copied the Qur'an more than a thousand times.

- Yusuf Islam (born Steven Demetre Georgiou; 21 July 1948, aka Cat Stevens) the famous singer of Cypriot Greek origin, converted to Islam at the height of his fame in December 1977[171] and adopted his Muslim name, Yusuf Islam, the following year.

See also

References

- 1 2 Mackridge, Peter (1987). "Greek-speaking Moslems of north-east Turkey: prolegomena to a study of the Ophitic sub-dialect of Pontic." Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies. 11. (1): 117.

- 1 2 3 Philliou, Christine (2008). "The Paradox of Perceptions: Interpreting the Ottoman Past through the National Present". Middle Eastern Studies. 44. (5): 672. "The second reason my services as an interpreter were not needed was that the current inhabitants of the village which had been vacated by apparently Turkish-speaking Christians en route to Kavala, were descended from Greek-speaking Muslims that had left Crete in a later stage of the same population exchange. It was not infrequent for members of these groups, settled predominantly along coastal Anatolia and the Marmara Sea littoral in Turkey, to be unaware that the language they were speaking was Greek. Again, it was not illegal for them to be speaking Greek publicly in Turkey, but it undermined the principle that Turks speak Turkish, just like Frenchmen speak French and Russians speak Russian."

- 1 2 3 Lambros Baltsiotis (2011). The Muslim Chams of Northwestern Greece: The grounds for the expulsion of a "non-existent" minority community. European Journal of Turkish Studies. "It's worth mentioning that the Greek speaking Muslim communities, which were the majority population at Yanina and Paramythia, and of substantial numbers in Parga and probably Preveza, shared the same route of identity construction, with no evident differentiation between them and their Albanian speaking co-habitants."

- 1 2 3 4 Koukoudis, Asterios (2003). The Vlachs: Metropolis and Diaspora. Zitros. p. 198. "In the mid-seventeenth century, the inhabitants of many of the villages in the upper Aliakmon valley-in the areas of Grevena, Anaselitsa or Voio, and Kastoria— gradually converted to Islam. Among them were a number of Kupatshari, who continued to speak Greek, however, and to observe many of their old Christian customs. The Islamicised Greek-speaking inhabitants of these areas came to be better known as "Valaades". They were also called "Foutsides", while to the Vlachs of the Grevena area they were also known as "Vlăhútsi". According to Greek statistics, in 1923 Anavrytia (Vrastino), Kastro, Kyrakali, and Pigadtisa were inhabited exclusively by Moslems (i.e Valaades), while Elatos (Dovrani), Doxaros (Boura), Kalamitsi, Felli, and Melissi (Plessia) were inhabited by Moslem Valaades and Christian Kupatshari. There were also Valaades living in Grevena, as also in other villages to the north and east of the town. ... the term "Valaades" refers to Greek-speaking Moslems not only of the Grevena area but also of Anaselitsa. In 1924, despite even their own objections, the last of the Valaades being Moslems, were forced to leave Greece under the terms of the compulsory exchange of populations between Greece and Turkey. Until then they had been almost entirely Greek-speakers. Many of the descendants of the Valaades of Anaseltisa, now scattered through Turkey and particularly Eastern Thrace (in such towns as Kumburgaz, Büyükçekmece, and Çatalca), still speak Greek dialect of Western Macedonia, which, significantly, they themselves call Romeïka "the language of the Romii". It is worth noting the recent research carried out by Kemal Yalçin, which puts a human face on the fate of 120 or so families from Anavryta and Kastro, who were involved in the exchange of populations. They set sail from Thessaloniki for Izmir, and from there settled en bloc in the village of Honaz near Denizli."

- 1 2 Beckingham, Charles Fraser (1957). "The Turks of Cyprus." Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 87. (2): 170–171. "While many Turks habitually speak Turkish there are 'Turkish', that is, Muslim villages in which the normal language is Greek; among them are Lapithou, Platanisso, Ayios Simeon and Galinoporni. This fact has not yet been adequately investigated. With the growth of national feeling and the spread of education the phenomenon is becoming not only rarer but harder to detect. In a Muslim village the school teacher will be a Turk and will teach the children Turkish. They already think of themselves as Turks, and having once learnt the language, will sometimes use it in talking to a visitor in preference to Greek, merely as matter of national pride. It has been suggested that these Greek-speaking Muslims are descended from Turkish- speaking immigrants who have retained their faith but abandoned their language because of the greater flexibility and commercial usefulness of Greek. It is open to the objection that these villages are situated in the remoter parts of the island, in the western mountains and in the Carpass peninsula, where most of the inhabitants are poor farmers whose commercial dealings are very limited. Moreover, if Greek had gradually replaced Turkish in these villages, one would have expected this to happen in isolated places, where a Turkish settlement is surrounded by Greek villages rather than where there are a number of Turkish villages close together as there are in the Carpass. Yet Ayios Simeon (F I), Ayios Andronikos (F I), and Galinoporni (F I) are all Greek-speaking, while the neighbouring village of Korovia (F I) is Turkish-speaking. It is more likely that these people are descended from Cypriots converted to Islam after 1571, who changed their religion but kept their language. This was the view of Menardos (1905, p. 415) and it is supported by the analogous case of Crete. There it is well known that many Cretans were converted to Islam, and there is ample evidence that Greek was almost the only language spoken by either community in the Cretan villages. Pashley (1837, vol. I, p. 8) ‘soon found that the whole rural population of Crete understands only Greek. The Aghás, who live in the principal towns, also know Turkish; although, even with them, Greek is essentially the mother-tongue.’"

- 1 2 Werner, Arnold (2000). "The Arabic dialects in the Turkish province of Hatay and the Aramaic dialects in the Syrian mountains of Qalamun: two minority languages compared". In Owens, Jonathan, (ed.). Arabic as a minority language. Walter de Gruyter. p. 358. "Greek speaking Cretan Muslims".

- 1 2 Mackridge, Peter (2010). Language and national identity in Greece, 1766–1976. Oxford University Press. p. 65. "Greek-speaking Muslims have not usually been considered as belonging to the Greek nation. Some communities of Greek-speaking Muslims lived in Macedonia. Muslims, most of them native speakers of Greek, formed a slight majority of the population of Crete in the early nineteenth century. The vast majority of these were descended from Christians who had voluntarily converted to Islam in the period following the Ottoman conquest of the island in 1669."

- ↑ Barbour, S., Language and Nationalism in Europe, Oxford University Press, 2000, ISBN 0-19-823671-9

- ↑ Hodgson, Marshall (2009). The Venture of Islam, Volume 3: The Gunpower Empires and Modern Times. University of Chicago Press. Chicago. pp. 262–263. "Islam, to be sure, remained, but chiefly as woven into the character of the Turkish folk. On this level, even Kemal, unbeliever as he was, was loyal to the Muslim community as such. Kemal would not let a Muslim-born girl be married to an infidel. Especially in the early years (as was illustrated in the transfer of populations with Greece) being a Turk was still defined more by religion than by language: Greek-speaking Muslims were Turks (and indeed they wrote their Greek with the Turkish letters) and Turkish-speaking Christians were Greeks (they wrote their Turkish with Greek letters). Though language was the ultimate criterion of the community, the folk-religion was so important that it might outweigh even language in determining basic cultural allegiance, within a local context."

- 1 2 3 Poulton, Hugh (2000). "The Muslim experience in the Balkan states, 1919‐1991." Nationalities Papers. 28. (1): 46. "In these exchanges, due to the influence of the millet system (see below), religion not ethnicity or language was the key factor, with all the Muslims expelled from Greece seen as "Turks," and all the Orthodox people expelled from Turkey seen as "Greeks" regardless of mother tongue or ethnicity."

- ↑ See Hugh Poulton, 'The Balkans: minorities and states in conflict', Minority Rights Publications, 1991.

- ↑ Taxation in the Ottoman Empire

- ↑ Νικόλαος Φιλιππίδης (1900). Επίτομος Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους 1453–1821. Εν Αθήναις: Εκ του Τυπογραφείου Α. Καλαράκη. Ανακτήθηκε στις 23 Ιουλίου 2010.

- ↑ Ιωάννης Λυκούρης (1954). Η διοίκησις και δικαιοσύνη των τουρκοκρατούμενων νήσων : Αίγινα – Πόρος – Σπέτσαι – Ύδρα κλπ., επί τη βάσει εγγράφων του ιστορικού αρχείου Ύδρας και άλλων. Αθήνα. Ανακτήθηκε στις 7 Δεκεμβρίου 2010.

- ↑ Παναγής Σκουζές (1777–1847) (1948). Χρονικό της σκλαβωμένης Αθήνας στα χρόνια της τυρανίας του Χατζή Αλή (1774–1796). Αθήνα: Α. Κολολού. Ανακτήθηκε στις 6 Ιανουαρίου 2011.

- ↑ Yılmaz, Gülay (1 December 2015). "The Devshirme System and the Levied Children of Bursa in 1603-4". Belleten (in Turkish). 79 (286): 901–930. doi:10.37879/belleten.2015.901. ISSN 0041-4255.

- ↑ Ortaylı, İlber. "Son İmparatorluk Osmanlı (The Last Empire: Ottoman Empire)", İstanbul, Timaş Yayınları (Timaş Press), 2006. pp. 87–89. ISBN 975-263-490-7 (in Turkish).

- ↑ Eastern Europe: An Introduction to the People, Lands, and Culture, Richard C. Frucht, ISBN 1-57607-800-0, ABC-CLIO, 2005, p. 803.

- ↑ Yeʼor, Bat (2002). Islam and Dhimmitude: where civilizations collide. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-8386-3943-6. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

At the request of Sultan Mahmud II (1803-39), Muhammed Ali sent the Egyptian army to subdue a Greek revolt. In 1823 the re-attachment of Crete to the pashlik of Crete created a base from which to attack the Greeks. Egyptian troops led by Ibrahim Pasha, the adopted son of Muhammad Ali, proceeded to devastate the island completely; villages were burned down, plantations uprooted, populations driven out or led away as slaves, and vast numbers of Greek slaves were deported to Egypt. This policy was pursued in the Morea where Ibrahim organized systematic devastation, with massive Islamization of Greek children. He sent sacks of heads and ears to the sultan in Constantinople and cargoes of Greek slaves to Egypt.

- ↑ Wilkinson, Sir John Gardner (1843). Modern Egypt and Thebes: Being a Description of Egypt; Including the Information Required for Travellers in that County, Volume 1. J. Murray. pp. 247–249. OCLC 3988717.

White Slaves. — In Egypt there are white slaves and slaves of colour. [...] There are also some Greeks who were taken in the War of Independence. [...] In like manner in Egypt, the officers of rank are for the most part enfranchised slaves. I have seen in the bazars of Cairo Greek slaves who had been torn from their country, at the time it was about to obtain its liberty; I have seen them afterwards holding nearly all the most important civil and military grades; and one might be almost tempted to think that their servitude was not a misfortune, if one could forget the grief of their parents on seeing them carried off, at a time when they hoped to bequeath to them a religion free from persecution, and a regenerated country.

- ↑ Sharkey, Heather J. (2009). A History of Muslims, Christians, and Jews in the Middle East. Cambridge University Press. p. 74. "To signal conversion, converts changed their clothes to brighter Muslim clothes — in the sixteenth century, for example, by abandoning the gray outer coats and flat, black-topped shoes that an edict prescribed for Christian and Jewish men."

- ↑ Sharkey, p. 74. "Thus, for example, a Greek verb for converting to Islam was tourkevo, meaning literally "to become a Turk."

- ↑ The New Encyclopedia of Islam, ed. Cyril Glassé, Rowman & Littlefield, 2008, p.129

- ↑ Mackridge. Greek-speaking Moslems of north-east Turkey. 1987. p. 115-116.

- ↑ Özkan, Hakan (2013). "The Pontic Greek spoken by Muslims in the villages of Beşköy in the province of present-day Trabzon." Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies. 37. (1): 130–131.

- 1 2 3 4 Hakan. The Pontic Greek spoken by Muslims. 2013. p. 131.

- 1 2 Schreiber, Laurentia (2015).Assessing sociolinguistic vitality: an attitudinal study of Rumca (Romeyka). (Thesis). Free University of Berlin. p. 12. "Moreover, in comparison with the number of inhabitants of Romeyka-speaking villages, the number of speakers must have been considerably higher (Özkan 2013). The number of speakers was estimated by respondents of the present study as between 1,000 and 5,000 speakers. They report, however, that the number of Rumca-speaking villages has decreased due to migration (7).(7) Trabzon’da ban köylerinde konuşuluyor. Diǧer köylerde de varmış ama unutulmuş. Çaykaran’ın yüz yırmı köyu var Yüz yırmı köyünden hemen hemen yetmişinde konuşuluyor. F50 "[Rumca] is spoken in some villages at Trabzon. It was also spoken in the other villages but it has been forgotten. Çaykara has 120 villages. Rumca is more or less spoken in 70 of 120 villages.""; p.55. "Besides Turkish national identity, Rumca speakers have a strong Muslim identity (Bortone 2009, Ozkan 2013) functioning as a dissolution of the split between Rumca and Turkish identity by emphasising common religious identity. Furthermore, the Muslim faith is used as a strong indicator of Turkishness. Emphasis on Turkish and Muslim identity entails at the same time rejection of any Rumca ethnic identity (Bortone 2009, Ozkan 2013) in relation to Greece, which is still considered an enemy country (Sitaridou 2013). Denial of any links to Greece goes so far that some female respondents from G2 even hesitated to mention the word Rum or Greek. On the one hand, respondents are aware of the Greek origin of Rumca and may even recognize shared cultural elements. Due to the lack of a distinct ethnic identity, Rumca speakers have no political identity and do not strive to gain national acknowledgement (Sitaridou 2013, Bortone 2009, Macktidge 1987)."

- ↑ Poutouridou, Margarita (1997). " Archived 18 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine The Of valley and the coming of Islam: The case of the Greek-speaking muslims." Bulletin of the Centre for Asia Minor Studies. 12: 47–70.

- ↑ Mackridge. Greek-speaking Moslems of north-east Turkey. 1987. p. 117. "lack of any apparent sense of identity other than Turkish".

- 1 2 3 Mackridge. Greek-speaking Moslems of north-east Turkey. 1987. p. 117.

- 1 2 Popov, Anton (2016). Culture, Ethnicity and Migration After Communism: The Pontic Greeks. Routledge. p. 54. ISBN 978-1-317-15579-9.

- ↑ Α. Υ.Ε., Κ. Υ.,Α/1920, Ο Ελληνισμός του Πόντου, Έκθεση του Αρχιμανδρίτη Πανάρετου, p.12

- ↑ Bortone, Pietro (2009). "Greek with no models, history or standard: Muslim Pontic Greek." In Silk, Michael & Alexandra Georgakopoulou (eds.). Standard languages and language standards: Greek, past and present. Ashgate Publishing. p. 68-69. "Muslim Pontic Greek speakers, on the other hand, did not regard themselves as in any way Greek. They therefore had no contact with Greeks from Greece, and no exposure to the language of Greece. To this day, they have never seen Modern Greek literature, have never heard Biblical Greek, have never studied classical Greek, have never learnt any Standard Greek (not even the Greek alphabet), have not heard Greek radio or TV, nor any form of the Greek language other than their own — and have not been touched by the strict Greek policies of language standardization, archaization and purism. In other words, their Greek has had no external models for centuries. Furthermore, it is not written, printed, or broadcast. So it has no recorded local tradition and therefore no internal models to refer back to either.".

- ↑ Hakan. The Pontic Greek spoken by Muslims. 2013. p. 137-138. "Trabzon is well known for its staunch nationalists. Beşköy is no exception to this rule. Because of the danger of being perceived as Greeks (Rum) clinging to their language and culture, or even worse as Pontians who seek ‘their lost kingdom of Pontus’ (which is an obscure accusation voiced by Turkish nationalists), it comes as no surprise that MP-speaking people are particularly sensitive to questions of identity. It has to be clarified at this point that the English term ‘Greek’ is not identical to the Turkish Rum, which means Greek-speaking people of Turkey. Nobody in Beşköy would identify themselves as Yunan, which denotes everything Greek coming from Greece (T. Yunanistan). However, as Rum is perceived in Turkey as linked in some way to Greece or the Orthodox Church, the Greek-speaking Muslims cannot easily present their language as their own, as other minorities in the Black Sea region such as the Laz do. In addition to the reasons stated above, many of the MP-speakers of Beşköy strive to be the best Turks and the most pious Muslims. I had no encounter with MP-speakers without the issue of identity being brought up in connection with their language. After a while the MP-speakers themselves would begin to say something on this very sensitive topic. Precisely because of the omnipresence and importance of this issue I cannot leave it uncommented in this introduction. Nevertheless, I did not question people systematically with the use of prepared questionnaires about their identity, their attitude vis-à-vis the language, i.e. if they like speaking it, if they want to pass it on to their children consciously, if they encountered difficulties because they speak MP, if they consider themselves of Turkish or Greek descent, if they can be Turks and Greeks at the same time, and how they regard Greece and the Pontians who live there. Appropriate answers to these very important sociolinguistic questions can only be found through extensive fieldwork that is endorsed by the Turkish authorities and a dedicated analysis of the data in a sizeable article or even a monograph. Nevertheless, I would like to dwell on some general tendencies that I have observed on the basis of the testimonies of my informants on their attitudes to language and identity. Of course I do not claim that these views are representative of MP-speakers in general, but they reflect the overwhelming impression I had during fieldwork in the region. Therefore I deem it necessary and valuable to give a voice to their opinions here. Many of the MP-speakers I met deny the Greekness of their language, although they know at least that many words in Standard Modern Greek (SMG) are identical to the ones in MP. As a linguist I was often asked to join them in their view in favour of the distinctness of their language. Without telling a lie I tried to reconcile the obvious truth that MP is a Greek dialect with the equally true assertion that MP and SMG are two different languages in the way that Italian and Spanish are distinct languages, to the extent that some characteristics are very similar and others completely different. In most cases they were satisfied with this answer."

- ↑ Hakan. The Pontic Greek spoken by Muslims. 2013. p. 132-133.

- 1 2 3 Hakan. The Pontic Greek spoken by Muslims. 2013. p. 133.

- ↑ Professor. Department of Near Eastern Studies. Princeton University

- ↑ Trabzon Şehrinin İslamlaşması ve Türkleşmesi 1461–1583 Archived 22 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine ISBN 975-518-116-4

- 1 2 Katsikas, Stefanos (2012). "Millet legacies in a national environment: Political elites and Muslim communities in Greece (1830s–1923)". In Fortna, Benjamin C., Stefanos Katsikas, Dimitris Kamouzis, & Paraskevas Konortas (eds). State-nationalisms in the Ottoman Empire, Greece and Turkey: Orthodox and Muslims, 1830–1945. Routledge. 2012. p.50. "Indeed, the Muslims of Greece included... Greek speaking (Crete and West Macedonia, known as Valaades)."

- 1 2 Dedes, Yorgos (2010). "Blame it on the Turko-Romnioi (Turkish Rums): A Muslim Cretan song on the abolition of the Janissaries". In Balta, Evangelia & Mehmet Ölmez (eds.). Turkish-Speaking Christians, Jews and Greek-Speaking Muslims and Catholics in the Ottoman Empire. Eren. Istanbul. p. 324. "Neither the younger generations of Ottoman specialists in Greece, nor specialist interested in Greek-speaking Muslims have not been much involved with these works, quite possibly because there is no substantial corpus of them."

- ↑ Tsitselikis, Konstantinos (2012). Old and New Islam in Greece: From historical minorities to immigrant newcomers. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 45. "In the same period, there was a search for common standards to govern state-citizen relations based on principles akin to the Greek national ideology. Thus the Muslims found themselves more in the position of a being a national minority group rather than a millet. The following example is evocative. After long discussions, the Cretan Assembly adopted the proposal to abolish soldiers’ cap visors especially for Muslim soldiers. Eleftherios Venizelos, a fervent supporter of upgrading Muslims’ institutional status, voted against this proposal because he believed that by adopting this measure the Assembly "would widen instead of fill the breach between Christians and Muslims, which is national rather than religious". As Greek Christians gradually began to envisage joining the Greek Kingdom through symbolic recognition of national ties to the ‘mother country’, the Muslim communities reacted and contemplated their alternative ‘mother nation’ or ‘mother state’, namely Turkishness and the Empire. Indicatively, Muslim deputies complained vigorously about a Declaration made by the plenary of the Cretan Assembly which stated that they body's works would be undertaken ‘in the name of the King of Greece’. The transformation of a millet into a nation, a process which unfolded in response to both internal dynamics and outside pressures, was well underway."