| Great Musgrave | |

|---|---|

Stone-built cottages in the main village street | |

| OS grid reference | NY767135 |

| Civil parish | |

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | KIRKBY STEPHEN |

| Postcode district | CA17 |

| Dialling code | 017683 |

| Police | Cumbria |

| Fire | Cumbria |

| Ambulance | North West |

| UK Parliament | |

Great Musgrave is a village and former civil parish, now in the parish of Musgrave, in the Eden district of Cumbria, England. It is about a mile west of Brough. In 1891 the parish had a population of 175.[1]

Great Musgrave sits atop a hill near the River Eden and Swindale Beck. Its location provides views over the vale of Eden and the nearby northern Pennines. The village name comes from the Musgrave family who lived here.

Church

Jul2006.jpg.webp)

The stone church of St Theobald, on the edge of the village, dates from 1845 to 1846, but two earlier churches (the first dating back to the 12th century) stood nearby. Unfortunately they were placed too close to the river and were subject to flooding. In 1822 the water was 3 feet (0.9 m) deep in the church.

Leading up to the present church with its slate roof is a row of horse chestnut trees. The square church tower contains two bells. The interior has one small stained glass window, a 13th-century coffin lid, a brass of a priest dated 1500 and carved heads on the roof beam corbels above the windows.

The church has an annual rush bearing ceremony on the first Saturday in July. Girls wear garlands of flowers, and boys carry rush crosses in a procession through the village and to the church where a service of praise and thanksgiving is then held.

History

On 30 December 1894 the parish was abolished and merged with "Little Musgrave" to form "Musgrave".[2]

The village was served by Musgrave railway station which opened in 1862 and closed in 1952.

Infilling of railway bridge

In May and June 2021, the space under the B6259 road bridge at Great Musgrave, north of the former railway station, was filled with 1,600 tonnes of aggregate and concrete by Highways England, now known as National Highways.

The structure spanned a five-mile section of trackbed which local rail enthusiasts hoped to restore, linking the Eden Valley and Stainmore railways to create an 11-mile tourist line between Appleby and Kirkby Stephen.[3][4] Highways England claimed to have consulted both railways prior to the work taking place, but this was denied by the two organisations who wrote a letter of complaint to Nick Harris, the company's Acting Chief Executive.[5]

The infilling was carried out under emergency development powers, colloquially known as 'Class Q',[6] after officers from Eden District Council asked for the work to be paused whilst planning requirements were confirmed. Highways England's engineer refused, stating on 24 June 2021 that the works were required "to prevent the failure of the bridge and avert a collapse".[7]

However, in May 2022, Bill Harvey Associates, a company specialising in masonry arch bridges, published an in-depth study reviewing engineering evidence and inspection reports about the bridge, sourced from Highways England.[8] The report concluded that:

- There is no evidence in the reports examined to suggest a current or developing risk of collapse.

- There is no evidence for a current or likely emergency.

- All evidence presented suggests that the bridge is, as stated by the 2021 examiner, "in fair condition".[9]

The backlash against the Great Musgrave infill scheme became national news and the government intervened to pause infilling and demolition schemes at dozens of other railway bridges across the country.[10] Many civil engineers expressed shame and embarrassment at the negative impact on their professional reputation.[11]

Highways England was forced to apply for retrospective planning permission for the infilling works,[12] with Eden District Council receiving 911 objections and only two expressions of support.[13][14] Advised by planning officers to reject the application,[13] the council's planning committee unanimously refused retrospective planning permission on 16 June 2022.[15] Restoration of Great Musgrave bridge to its former condition, together with additional strengthening, could cost an estimated £431,000, in addition to the £124,000 spent on the initial infilling work.[14]

National Highways has agreed to abide by an enforcement notice issued by Eden District Council which requires the infill to be removed and the surrounding landscape restored to its condition prior to the infilling works. This notice became effective on 11 October 2022 and the work must be completed within 12 months of this date.[16] In July 2023, National Highways' plans to restore the bridge and remove the infill were criticised by locals as they involved closing the bridge for three months, necessitating long local diversions for regular users of the B6259 which crosses the bridge.[17] Work began in August 2023 to remove the infill material.[18]

After the Great Musgrave outcry, National Highways developed a new way to determine the nature of major works to the disused railway structures it manages, with proposals reviewed by experts from heritage, environmental, planning and active travel organisations who collectively form the company's Stakeholder Advisory Forum.[13]

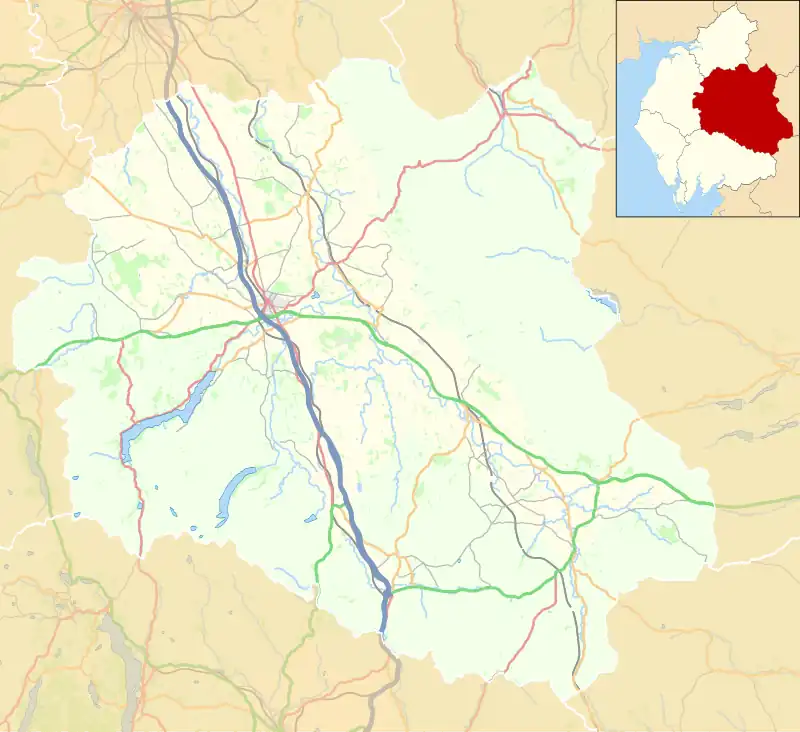

Location grid

See also

References

- ↑ "Population statistics Great Musgrave AP/CP through time". A Vision of Britain through Time. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ↑ "Relationships and changes Great Musgrave AP/CP through time". A Vision of Britain through Time. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ↑ "Highways England accused of rail heritage vandalism". The Construction Index. 30 June 2021. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- ↑ "Highways England accused of 'vandalism' after bridge infilled with concrete". ITV. 1 July 2021. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- ↑ "Cumbrian railways seek reparation in Highways England bridge row". Rail UK. 23 June 2021.

- ↑ The Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development) (England) Order 2015. Accessed: 4 July 2023

- ↑ "Email exchange between National Highways and Eden District Council" (PDF). What Do They Know?. 24 June 2021.

- ↑ "Great Musgrave bridge documentation" (PDF). The HRE Group.

- ↑ Bill Harvey Associates (9 May 2022). "Great Musgrave EDE/25" (PDF).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Marsh, Sarah (30 July 2021). "Britain's Victorian railway bridges may be saved in new green travel plan". The Guardian.

- ↑ "'Ashamed to be an engineer': NCE readers react to Highways England bridge infilling". New Civil Engineer. 15 July 2021.

- ↑ Peskett, Ted (24 July 2021). "Eden District Council say Highways England must apply to retain Great Musgrave Bridge infilling". News & Star / Cumberland News. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- 1 2 3 Horgan, Rob (10 June 2022). "National Highways' bridge infilling application dealt blow by planning officials". New Civil Engineer. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- 1 2 Weaver, Matthew (9 May 2022). "Cumbrian council may reverse concrete infilling of Victorian bridge". Guardian. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- ↑ "Great Musgrave bridge: Concrete infill refused must be removed". BBC News. 16 June 2022. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- ↑ "Great Musgrave bridge: Concrete must be removed by October 2023". BBC News. 6 October 2022. Retrieved 6 October 2022.

- ↑ "National Highways slammed again over Great Musgrave bridge fiasco". The Construction Index. 4 July 2023. Retrieved 4 July 2023.

- ↑ Weaver, Matthew (14 August 2023). "Roads agency starts to undo its 'vandalism' of Victorian bridge". Guardian. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

External links

- Cumbria County History Trust: Musgrave (nb: provisional research only – see Talk page)

- Illustrated information about its church

- Map sources for Great Musgrave