The Gold effect is the phenomenon in which a scientific idea, particularly in medicine, is developed to the status of an accepted position within a professional body or association by the social process itself of scientific conferences, committees, and consensus building, despite not being supported by conclusive evidence. The Gold effect is used to analyze errors in public health policy and practice, such as the widespread use of cholesterol screening in the prevention of cardiovascular disease.[1]

The effect was described by Thomas Gold in 1979.[2] The effect was reviewed by Petr Skrabanek and James McCormick in their book Follies and Fallacies in Medicine.[3] In their book, Skrabanek and McCormick describe the Gold effect as: "At the beginning a few people arrive at a state of near belief in some idea. A meeting is held to discuss the pros and cons of the idea. More people favouring the idea than those disinterested will be present. A representative committee will be nominated to prepare a collective volume to propagate and foster interest in the idea. The totality of resulting articles based on the idea will appear to show an increasing consensus. A specialized journal will be launched. Only orthodox or near orthodox articles will pass the referees and the editor."

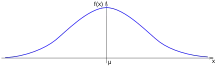

The progression of the Gold effect was described by mathematician Raymond Lyttleton. According to Lyttleton, the area under the curve of a gaussian curve represents the number of people concerned with a particular subject. As the Gold effect progresses and more and more people start believing a particular idea, the gaussian curve starts to concentrate more around the center. By the end, the gaussian function will have become a delta function, representing everyone as a believer (infinite value at 0), with no non-believers.

References

- ↑ Hann, Alison; Peckham, Stephen (February 2010). "Cholesterol screening and the Gold Effect". Health, Risk & Society. 12 (1): 33–50. doi:10.1080/13698570903499608. S2CID 58131831.

- ↑ Duncan, Roland (1979). Lying Truths. A critical scrutiny of current beliefs and conventions. Oxford: Pergamon Press. pp. 182–198. ISBN 0080219780.

- ↑ Skrabanek, Petr; McCormick, James (1998). Follies and Fallacies in Medicine (Third ed.). Whithorn (UK): Tarragon Press. pp. 54–55. ISBN 1870781090.