George Hakewill | |

|---|---|

George Hakewill, contemporary portrait, collection of Exeter College, Oxford | |

| Born | 1578 Barnstaple, Devon, England |

| Died | 5 April 1649 (aged 71) |

| Resting place | 51°06′00″N 4°08′26″W / 51.099953°N 4.140657°W |

| Alma mater | Exeter College Oxford |

| Occupation | Divine |

| Spouse | Mary nee Ayers |

%252C_by_Sylvester_Harding_(1745-1809).jpg.webp)

George Hakewill (1578 or 1579[2] – 1649) was an English clergyman and author.

Early life

Born in Exeter, he studied at Alban Hall, University of Oxford,[3] where he was a noted disputant and orator[4] and in June 1596, only a year after his matriculation and at the unusually early age of 18, he was elected a fellow of Exeter College. There he proceeded B.A. in 1599, and M.A. in 1602. In 1604 he obtained leave to travel and spent the next four years in Europe, mainly with Swiss and German Calvinists, spending a winter at the University of Heidelberg with David Pareas and Abraham Scultetus . [5]

Royal service

Of strongly anti-Catholic and pro-Calvinist religious views, Hakewill was one of the two clergymen appointed in 1612 to preserve Prince Charles "from the inroads of popery."

He wrote strongly in defense of the then Calvinist position of the Anglican Church[6]

In 1616, possibly by the prince's means, he had been appointed Archdeacon of Surrey and his further rise through the ranks of the church seemed assured. His decision however in 1622 to present the prince with a treatise written by himself and arguing against the ongoing negotiations for a Spanish match led to the abrupt end of his career at court. The treatise was shown to the prince's father, James I of England, who committed Hakewill to a prison for a brief period and appointed Lancelot Andrewes to rebut the tract.[7]

Later life

Despite this setback in 1624 Hakewill single-handedly paid for the building of Exeter College chapel (consecrated 15 October 1624), at a cost of £1200.[7] (In his will he requested that his heart be buried there,[8] though there is no evidence this was carried out.)

Hakewill was eventually made Rector of Exeter College (elected 23 August 1642; 18 admitted November 1642). He however "did little, or not at all, reside upon that rectory: For the civil wars breaking out, he returned to his parsonage...where he lived a retired life to the time of his death."[9] The parsonage in question was the Rectory of Heanton Punchardon near Barnstaple in Devon, to which he had been presented by his kinsman Sir Robert Basset.[7]

His works include: The Vanitie of the Eie. First beganne for the comfort of a gentlewoman bereaved of her sight and since upon occasion inlarged (second edition, 1608; third edition, 1615; and another impression, 1633); a Latin treatise against regicides (1612); and Apologie ... of the Power and Providence of God (1627). [10] The latter work, a rebuttal of the view that creation, including humanity, was gradually declining, was praised by Samuel Pepys[11] and is cited by James Boswell as one of the formative influences on the prose of Samuel Johnson.[7] Hakewill's style has been described as "lively and forceful".[7]

By a brief marriage to Mary Ayer or Ayers (née Delbridge) Hakewill had two sons, John and George. George appears to have died in childhood. After becoming a fellow of Exeter College, John also died within his father's lifetime in 1637. Hakewill's will shows that, despite his theological leanings towards radical Protestantism, he remained politically a royalist[12] and loyal to the Church of England as established.[13] He also left a bequest to his "dear brother" William Hakewill, a noted supporter of the opposing Parliamentarian party. He named his nephew John Hakewill executor of his will, proved 2 May 1649.[14]

George Hakewill was buried in the chancel of his church in Heanton Punchardon on 5 April 1649.

References

- ↑ Vivian, Lt.Col. J.L., (Ed.) The Visitations of the County of Devon: Comprising the Heralds' Visitations of 1531, 1564 & 1620, Exeter, 1895, p.437

- ↑ James Granger (1812). "Biography". Retrieved 19 October 2008.

- ↑ Alumni Oxonienses 1500-1714, Haak-Harman

- ↑ Alexander Chalmers (1812). "Biography". Retrieved 19 October 2008.

- ↑ P. E. McCullough, 'Hakewill, George (bap. 1578, d. 1649)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Sept 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 retrieved 19 July 2009

- ↑

Milton, Anthony (2002). Catholic and Reformed: The Roman and Protestant Churches in English Protestant Thought, 1600-1640 (Web). Anthony Fletcher, John Guy, John Morrill. p383: Cambridge University Press. p. 617. ISBN 978-0-521-89329-9. Retrieved 19 October 2008.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 McCullough, P. E. "Hakewill, George". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/11885. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

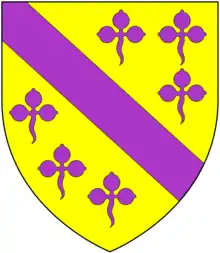

- ↑ "...my desire then is to bee buried in mine owne Church, and that my body being opned (if conveniently it may bee, my hart may bee embalmed, and buried in the foresaid Chappell under the Cumunion table, or the Deske uppon which the great bible lyes with this inscription in brasse layd upon it, Cor meum ad te Domine": Will of George Hakewill, 1649. ('Cor meum ad te Domine' was the motto on the Hakewill coat-of-arms.)

- ↑ Prince, John. (1701). The Worthies of Devon

- ↑ Wadsworth, Robert Woodman (1935). "The life and works of Dr. George Hakewill. "Masters essay. Columbia University. English.

- ↑ "Diary of Samuel Pepys".

- ↑ "...Thus beseeching Allmighty god to blesse the Kings Maty His Church and State by making up the unhappie and unnaturall breaches & Distractions thereof": Will of George Hakewill, 1649

- ↑ "...For my Religion in this lamentable varietie of new and strange opinions now on foot, I proffesse with St Hierome, In eadem religione in quȃ Infans baptizatus sum senex morior": Will of George Hakewill, 1649

- ↑ Anthony Wood (1690). "Biography". Retrieved 19 October 2008.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)