| Part of a series on |

| Genetic genealogy |

|---|

| Concepts |

| Related topics |

A genealogical DNA test is a DNA-based genetic test used in genetic genealogy that looks at specific locations of a person's genome in order to find or verify ancestral genealogical relationships, or (with lower reliability) to estimate the ethnic mixture of an individual. Since different testing companies use different ethnic reference groups and different matching algorithms, ethnicity estimates for an individual vary between tests, sometimes dramatically.

Three principal types of genealogical DNA tests are available, with each looking at a different part of the genome and being useful for different types of genealogical research: autosomal (atDNA), mitochondrial (mtDNA), and Y-chromosome (Y-DNA).

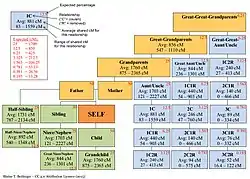

Autosomal tests may result in a large number of DNA matches to both males and females who have also tested with the same company. Each match will typically show an estimated degree of relatedness, i.e., a close family match, 1st-2nd cousins, 3rd-4th cousins, etc. The furthest degree of relationship is usually the "6th-cousin or further" level. However, due to the random nature of which, and how much, DNA is inherited by each tested person from their common ancestors, precise relationship conclusions can only be made for close relations. Traditional genealogical research, and the sharing of family trees, is typically required for interpretation of the results. Autosomal tests are also used in estimating ethnic mix.

MtDNA and Y-DNA tests are much more objective. However, they give considerably fewer DNA matches, if any (depending on the company doing the testing), since they are limited to relationships along a strict female line and a strict male line respectively. MtDNA and Y-DNA tests are utilized to identify archeological cultures and migration paths of a person's ancestors along a strict mother's line or a strict father's line. Based on MtDNA and Y-DNA, a person's haplogroup(s) can be identified. The mtDNA test can be taken by both males and females, because everyone inherits their mtDNA from their mother, as the mitochondrial DNA is located in the egg cell. However, a Y-DNA test can only be taken by a male, as only males have a Y-chromosome.

Procedure

A genealogical DNA test is performed on a DNA sample obtained by cheek-scraping (also known as a buccal swab), spit-cups, mouthwash, or chewing gum. Typically, the sample collection uses a home test kit supplied by a service provider such as 23andMe, AncestryDNA, Family Tree DNA, or MyHeritage. After following the kit instructions on how to collect the sample, it is returned to the supplier for analysis. The sample is then processed using a technology known as DNA microarray to obtain the genetic information.

Types of tests

There are three major types of genealogical DNA tests: Autosomal (which includes X-DNA), Y-DNA, and mtDNA.

- Autosomal DNA tests look at chromosome pairs 1–22 and the X part of the 23rd chromosome. The autosomes (chromosome pairs 1–22) are inherited from both parents and all recent ancestors. The X-chromosome follows a special inheritance pattern, because females (XX) inherit an X-chromosome from each of their parents, while males (XY) inherit an X-chromosome from their mother and a Y-chromosome from their father (XY). Ethnicity estimates are often included with this sort of testing.

- Y-DNA looks at the Y-chromosome, which is passed down from father to son. Thus, the Y-DNA test can only be taken by males to explore their direct paternal line.

- mtDNA looks at the mitochondria, which is passed down from mother to child. Thus, the mtDNA test can be taken by both males and females, and it explores one's direct maternal line.[1]

Y-DNA and mtDNA cannot be used for ethnicity estimates, but can be used to find one's haplogroup, which is unevenly distributed geographically.[2] Direct-to-consumer DNA test companies have often labeled haplogroups by continent or ethnicity (e.g., an "African haplogroup" or a "Viking haplogroup"), but these labels may be speculative or misleading.[2][3][4]

Autosomal DNA (atDNA) testing

Testing

Autosomal DNA is contained in the 22 pairs of chromosomes not involved in determining a person's sex.[2] Autosomal DNA recombines in each generation, and new offspring receive one set of chromosomes from each parent.[5] These are inherited exactly equally from both parents and roughly equally from grandparents to about 3x great-grandparents.[6] Therefore, the number of markers (one of two or more known variants in the genome at a particular location – known as Single-nucleotide polymorphisms or SNPs) inherited from a specific ancestor decreases by about half with each successive generation; that is, an individual receives half of their markers from each parent, about a quarter of those markers from each grandparent; about an eighth of those markers from each great-grandparent, etc. Inheritance is more random and unequal from more distant ancestors.[7] Generally, a genealogical DNA test might test about 700,000 SNPs (specific points in the genome).[8]

Reporting process

The preparation of a report on the DNA in the sample proceeds in multiple stages:

- identification of the DNA base pair at specific SNP locations

- comparison with previously stored results

- interpretation of matches

Base pair identification

All major service providers use equipment with chips supplied by Illumina.[9] The chip determines which SNP locations are tested. Different versions of the chip are used by different service providers. In addition, updated versions of the Illumina chip may test different sets of SNP locations. The list of SNP locations and base pairs at that location is usually available to the customer as "raw data". The raw data can be uploaded to some other genealogical service providers to produce an additional interpretation and matches. For additional genealogical analysis the data can also be uploaded to GEDmatch (a third-party web based set of tools that analyzes raw data from the main service providers). Raw data can also be uploaded to services that provide health risk and trait reports using SNP genotypes. These reports may be free or inexpensive, in contrast to reports provided by DTC testing companies, who charge about double the cost of their genealogy-only services. The implications of individual SNP results can be ascertained from raw data results by referring to SNPedia.com.

Identification of Matches

The major component of an autosomal DNA test is matching other individuals. Where the individual being tested has a number of consecutive SNPs in common with a previously tested individual in the company's database, it can be inferred that they share a segment of DNA at that part of their genomes.[10] If the segment is longer than a threshold amount set by the testing company, then these two individuals are considered to be a match. Unlike the identification of base pairs, the data bases against which the new sample is tested, and the algorithms used to determine a match, are proprietary and specific to each company.

The unit for segments of DNA is the centimorgan (cM). For comparison, a full human genome is about 6500 cM. The shorter the length of a match, the greater are the chances that a match is spurious.[11] An important statistic for subsequent interpretation is the length of the shared DNA (or the percentage of the genome that is shared).

Interpretation of Autosomal matches

Most companies will show the customers how many cMs they share and across how many segments. From the number of cMs and segments, the relationship between the two individuals can be estimated; however, due to the random nature of DNA inheritance, relationship estimates, especially for distant relatives, are only approximate. Some more distant cousins will not match at all.[12] Although information about specific SNPs can be used for some purposes (e.g., suggesting likely eye color), the key information is the percentage of DNA shared by two individuals. This can indicate the closeness of the relationship. However, it does not show the roles of the two individuals, e.g., 50% shared suggests a parent/child relationship, but it does not identify which individual is the parent.

Various advanced techniques and analyses can be done on this data. This includes features such as In-common/Shared Matches,[13] Chromosome Browsers,[14] and Triangulation.[15] This analysis is often required if DNA evidence is being used to prove or disprove a specific relationship.

X-chromosome DNA testing

The X-chromosome SNP results are often included in autosomal DNA tests. Both males and females receive an X-chromosome from their mother, but only females receive a second X-chromosome from their father.[16] The X-chromosome has a special path of inheritance patterns and can be useful in significantly narrowing down possible ancestor lines compared to autosomal DNA. For example, an X-chromosome match with a male can only have come from his maternal side.[17] Like autosomal DNA, X-chromosome DNA undergoes random recombination at each generation (except for father-to-daughter X-chromosomes, which are passed down unchanged). There are specialized inheritance charts which describe the possible patterns of X-chromosome DNA inheritance for males and females.[18]

STRs

Some genealogical companies offer autosomal STRs (short tandem repeats).[19] These are similar to Y-DNA STRs. The number of STRs offered is limited, and results have been used for personal identification,[20] paternity cases, and inter-population studies.[21][22]

Law enforcement agencies in the US and Europe use autosomal STR data to identify criminals.[19][23]

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) testing

The mitochondrion is a component of a human cell, and contains its own DNA. Mitochondrial DNA usually has 16,569 base pairs (the number can vary slightly depending on addition or deletion mutations)[24] and is much smaller than the human genome DNA which has 3.2 billion base pairs. Mitochondrial DNA is transmitted from mother to child, as it is contained in the egg cell. Thus, a direct maternal ancestor can be traced using mtDNA. The transmission occurs with relatively rare mutations compared to autosomal DNA. A perfect match found to another person's mtDNA test results indicates shared ancestry of possibly between 1 and 50 generations ago.[2] More distant matching to a specific haplogroup or subclade may be linked to a common geographic origin.

Test

The mtDNA, by current conventions, is divided into three regions. They are the coding region (00577-16023) and two Hyper Variable Regions (HVR1 [16024-16569], and HVR2 [00001-00576]).[25]

The two most common mtDNA tests are a sequence of HVR1 and HVR2 and a full sequence of the mitochondria. Generally, testing only the HVRs has limited genealogical use so it is increasingly popular and accessible to have a full sequence. The full mtDNA sequence is only offered by Family Tree DNA among the major testing companies[26] and is somewhat controversial because the coding region DNA may reveal medical information about the test-taker[27]

Haplogroups

All humans descend in the direct female line from Mitochondrial Eve, a female who lived probably around 150,000 years ago in Africa.[28][29] Different branches of her descendants are different haplogroups. Most mtDNA results include a prediction or exact assertion of one's mtDNA Haplogroup. Mitochrondial haplogroups were greatly popularized by the book The Seven Daughters of Eve, which explores mitochondrial DNA.

Understanding mtDNA test results

It is not normal for test results to give a base-by-base list of results. Instead, results are normally compared to the Cambridge Reference Sequence (CRS), which is the mitochondria of a European who was the first person to have their mtDNA published in 1981 (and revised in 1999).[30] Differences between the CRS and testers are usually very few, thus it is more convenient than listing one's raw results for each base pair.

- Examples

Note that in HVR1, instead of reporting the base pair exactly, for example 16,111, the 16 is often removed to give in this example 111. The letters refer to one of the four bases (A, T, G, C) that make up DNA.

| Region | HVR1 | HVR2 |

|---|---|---|

| Differences from CRS | 111T,223T,259T,290T,319A,362C | 073G,146C,153G |

Y-chromosome (Y-DNA) testing

The Y-chromosome is one of the 23rd pair of human chromosomes. Only males have a Y-chromosome, because women have two X chromosomes in their 23rd pair. A man's patrilineal ancestry, or male-line ancestry, can be traced using the DNA on his Y-chromosome (Y-DNA), because the Y-chromosome is transmitted from a father to son nearly unchanged.[31] A man's test results are compared to another man's results to determine the time frame in which the two individuals shared a most recent common ancestor, or MRCA, in their direct patrilineal lines. If their test results are very close, they are related within a genealogically useful time frame.[32] A surname project is where many individuals whose Y-chromosomes match collaborate to find their common ancestry.

Women who wish to determine their direct paternal DNA ancestry can ask their father, brother, paternal uncle, paternal grandfather, or a paternal uncle's son (their cousin) to take a test for them.

There are two types of DNA testing: STRs and SNPs.[2]

STR markers

Most common is STRs (short tandem repeat). A certain section of DNA is examined for a pattern that repeats (e.g. ATCG). The number of times it repeats is the value of the marker. Typical tests test between 12 and 111 STR markers. STRs mutate fairly frequently. The results of two individuals are then compared to see if there is a match. DNA companies will usually provide an estimate of how closely related two people are, in terms of generations or years, based on the difference between their results.[33]

SNP markers and Haplogroups

A person's haplogroup can often be inferred from their STR results, but can be proven only with a Y-chromosome SNP test (Y-SNP test).

A single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) is a change to a single nucleotide in a DNA sequence. Typical Y-DNA SNP tests test about 20,000 to 35,000 SNPs.[34] Getting a SNP test allows a much higher resolution than STRs. It can be used to provide additional information about the relationship between two individuals and to confirm haplogroups.

All human men descend in the paternal line from a single man dubbed Y-chromosomal Adam, who lived probably between 200,000 and 300,000 years ago.[35][36] A 'family tree' can be drawn showing how men today descend from him. Different branches of this tree are different haplogroups. Most haplogroups can be further subdivided multiple times into sub-clades. Some known sub-clades were founded in the last 1000 years, meaning their timeframe approaches the genealogical era (c.1500 onwards).[37]

New sub-clades of haplogroups may be discovered when an individual tests, especially if they are non-European. Most significant of these new discoveries was in 2013 when the haplogroup A00 was discovered, which required theories about Y-chromosomal Adam to be significantly revised. The haplogroup was discovered when an African-American man tested STRs at FamilyTreeDNA and his results were found to be unusual. SNP testing confirmed that he does not descend patrilineally from the "old" Y-chromosomal Adam and so a much older man became Y-Chromosomal Adam.

Using DNA test results

Ethnicity estimates

Many companies offer a percentage breakdown by ethnicity or region. Generally the world is specified into about 20–25 regions, and the approximate percentage of DNA inherited from each is stated. This is usually done by comparing the frequency of each Autosomal DNA marker tested to many population groups.[2] The reliability of this type of test is dependent on comparative population size, the number of markers tested, the ancestry informative value of the SNPs tested, and the degree of admixture in the person tested. Earlier ethnicity estimates were often wildly inaccurate, but as companies receive more samples over time, ethnicity estimates have become more accurate. Testing companies such as Ancestry.com will often regularly update their ethnicity estimates, which has caused some controversy from customers as their results update.[38][39] Usually the results at the continental level are accurate, but more specific assertions of the test may turn out to be incorrect.

Audience

The interest in genealogical DNA tests has been linked to both an increase in curiosity about traditional genealogy and to more general personal origins. Those who test for traditional genealogy often utilize a combination of autosomal, mitochondrial, and Y-Chromosome tests. Those with an interest in personal ethnic origins are more likely to use an autosomal test. However, answering specific questions about the ethnic origins of a particular lineage may be best suited to an mtDNA test or a Y-DNA test.

Maternal origin tests

For recent genealogy, exact matching on the mtDNA full sequence is used to confirm a common ancestor on the direct maternal line between two suspected relatives. Because mtDNA mutations are very rare, a nearly perfect match is not usually considered relevant to the most recent 1 to 16 generations.[40] In cultures lacking matrilineal surnames to pass down, neither relative above is likely to have as many generations of ancestors in their matrilineal information table as in the above patrilineal or Y-DNA case: for further information on this difficulty in traditional genealogy, due to lack of matrilineal surnames (or matrinames), see Matriname.[41] However, the foundation of testing is still two suspected descendants of one person. This hypothesize and test DNA pattern is the same one used for autosomal DNA and Y-DNA.

Tests for ethnicity and membership of other groups

_PC_analysis.png.webp)

As discussed above, autosomal tests usually report the ethnic proportions of the individual. These attempt to measure an individual's mixed geographic heritage by identifying particular markers, called ancestry informative markers or AIM, that are associated with populations of specific geographical areas. Geneticist Adam Rutherford has written that these tests "don’t necessarily show your geographical origins in the past. They show with whom you have common ancestry today."[42]

The haplogroups determined by Y-DNA and mtDNA tests are often unevenly geographically distributed. Many direct-to-consumer DNA tests described this association to infer the test-taker's ancestral homeland.[4] Most tests describe haplogroups according to their most frequently associated continent (e.g., a "European haplogroup").[4] When Leslie Emery and collaborators performed a trial of mtDNA haplogroups as a predictor of continental origin on individuals in the Human Genetic Diversity Panel (HGDP) and 1000 Genomes (1KGP) datasets, they found that only 14 of 23 haplogroups had a success rate above 50% among the HGDP samples, as did "about half" of the haplogroups in the 1KGP.[4] The authors concluded that, for most people, "mtDNA-haplogroup membership provides limited information about either continental ancestry or continental region of origin."[4]

African ancestry

Y-DNA and mtDNA testing may be able to determine with which peoples in present-day Africa a person shares a direct line of part of his or her ancestry, but patterns of historic migration and historical events cloud the tracing of ancestral groups. Due to joint long histories in the US, approximately 30% of African American males have a European Y-Chromosome haplogroup[43] Approximately 58% of African Americans have at least the equivalent of one great-grandparent (13%) of European ancestry. Only about 5% have the equivalent of one great-grandparent of Native American ancestry. By the early 19th century, substantial families of Free Persons of Color had been established in the Chesapeake Bay area who were descended from free people during the colonial period; most of those have been documented as descended from white men and African women (servant, slave or free). Over time various groups married more within mixed-race, black or white communities.[44]

According to authorities like Salas, nearly three-quarters of the ancestors of African Americans taken in slavery came from regions of West Africa. The African-American movement to discover and identify with ancestral tribes has burgeoned since DNA testing became available. African Americans usually cannot easily trace their ancestry during the years of slavery through surname research, census and property records, and other traditional means. Genealogical DNA testing may provide a tie to regional African heritage.

United States – Melungeon testing

Melungeons are one of numerous multiracial groups in the United States with origins wrapped in myth. The historical research of Paul Heinegg has documented that many of the Melungeon groups in the Upper South were descended from mixed-race people who were free in colonial Virginia and the result of unions between the Europeans and Africans. They moved to the frontiers of Virginia, North Carolina, Kentucky and Tennessee to gain some freedom from the racial barriers of the plantation areas.[45] Several efforts, including a number of ongoing studies, have examined the genetic makeup of families historically identified as Melungeon. Most results point primarily to a mixture of European and African, which is supported by historical documentation. Some may have Native American heritage as well. Though some companies provide additional Melungeon research materials with Y-DNA and mtDNA tests, any test will allow comparisons with the results of current and past Melungeon DNA studies.

Native American ancestry

The pre-columbian indigenous people of the United States are called "Native Americans" in American English.[46] Autosomal testing, Y-DNA, and mtDNA testing can be conducted to determine the ancestry of Native Americans. A mitochondrial Haplogroup determination test based on mutations in Hypervariable Region 1 and 2 may establish whether a person's direct female line belongs to one of the canonical Native American Haplogroups, A, B, C, D or X. The vast majority of Native American individuals belong to one of the five identified mtDNA Haplogroups. Thus, being in one of those groups provides evidence of potential Native American descent. However, DNA ethnicity results cannot be used as a substitute for legal documentation.[47] Native American tribes have their own requirements for membership, often based on at least one of a person's ancestors having been included on tribal-specific Native American censuses (or final rolls) prepared during treaty-making, relocation to reservations or apportionment of land in the late 19th century and early 20th century. One example is the Dawes Rolls.

Cohanim ancestry

The Cohanim (or Kohanim) is a patrilineal priestly line of descent in Judaism. According to the Bible, the ancestor of the Cohanim is Aaron, brother of Moses. Many believe that descent from Aaron is verifiable with a Y-DNA test: the first published study in genealogical Y-Chromosome DNA testing found that a significant percentage of Cohens had distinctively similar DNA, rather more so than general Jewish or Middle Eastern populations. These Cohens tended to belong to Haplogroup J, with Y-STR values clustered unusually closely around a haplotype known as the Cohen Modal Haplotype (CMH). This could be consistent with a shared common ancestor, or with the hereditary priesthood having originally been founded from members of a single closely related clan.

Nevertheless, the original studies tested only six Y-STR markers, which is considered a low-resolution test. In response to the low resolution of the original 6-marker CMH, the testing company FTDNA released a 12-marker CMH signature that was more specific to the large closely related group of Cohens in Haplogroup J1.

A further academic study published in 2009 examined more STR markers and identified a more sharply defined SNP haplogroup, J1e* (now J1c3, also called J-P58*) for the J1 lineage. The research found "that 46.1% of Kohanim carry Y chromosomes belonging to a single paternal lineage (J-P58*) that likely originated in the Near East well before the dispersal of Jewish groups in the Diaspora. Support for a Near Eastern origin of this lineage comes from its high frequency in our sample of Bedouins, Yemenis (67%), and Jordanians (55%) and its precipitous drop in frequency as one moves away from Saudi Arabia and the Near East (Fig. 4). Moreover, there is a striking contrast between the relatively high frequency of J-58* in Jewish populations (»20%) and Kohanim (»46%) and its vanishingly low frequency in our sample of non-Jewish populations that hosted Jewish diaspora communities outside of the Near East."[48]

Recent phylogenetic research for haplogroup J-M267 placed the "Y-chromosomal Aaron" in a subhaplogroup of J-L862, L147.1 (age estimate 5631-6778yBP yBP): YSC235>PF4847/CTS11741>YSC234>ZS241>ZS227>Z18271 (age estimate 2731yBP).[49]

European testing

Benefits

Genealogical DNA tests have become popular due to the ease of testing at home and their usefulness in supplementing genealogical research. Genealogical DNA tests allow for an individual to determine with high accuracy whether he or she is related to another person within a certain time frame, or with certainty that he or she is not related. DNA tests are perceived as more scientific, conclusive and expeditious than searching the civil records. However, they are limited by restrictions on lines that may be studied. The civil records are always only as accurate as the individuals having provided or written the information.

Y-DNA testing results are normally stated as probabilities: For example, with the same surname a perfect 37/37 marker test match gives a 95% likelihood of the most recent common ancestor (MRCA) being within 8 generations,[50] while a 111 of 111 marker match gives the same 95% likelihood of the MRCA being within only 5 generations back.[51]

As presented above in mtDNA testing, if a perfect match is found, the mtDNA test results can be helpful. In some cases, research according to traditional genealogy methods encounters difficulties due to the lack of regularly recorded matrilineal surname information in many cultures (see Matrilineal surname).[41]

Autosomal DNA combined with genealogical research has been used by adoptees to find their biological parents,[52] has been used to find the name and family of unidentified bodies[53][54] and by law enforcement agencies to apprehend criminals[55][56] (for example, the Contra Costa County District Attorney's office used the "open-source" genetic genealogy site GEDmatch to find relatives of the suspect in the Golden State Killer case.[57][58]). The Atlantic magazine commented in 2018 that "Now, the floodgates are open. ..a small, volunteer-run website, GEDmatch.com, has become ... the de facto DNA and genealogy database for all of law enforcement."[59] Family Tree DNA announced in February 2019 it was allowing the FBI to access its DNA data for cases of murder and rape.[60] However, in May 2019 GEDmatch initiated stricter rules for accessing their autosomal DNA database[61] and Family Tree DNA shut down their Y-DNA database ysearch.org, making it more difficult for law enforcement agencies to solve cases.[62]

Drawbacks

Common concerns about genealogical DNA testing are cost and privacy issues.[63] Some testing companies, such as 23andMe and Ancestry,[64] retain samples and results for their own use without a privacy agreement with subjects.[65][66]

Autosomal DNA tests can identify relationships but they can be misinterpreted.[67][68][69] For example, transplants of stem cell or bone marrow will produce matches with the donor. In addition, identical twins (who have identical DNA) can give unexpected results.[70]

Testing of the Y-DNA lineage from father to son may reveal complications, due to unusual mutations, secret adoptions, and non-paternity events (i.e., that the perceived father in a generation is not the father indicated by written birth records).[71] According to the Ancestry and Ancestry Testing Task Force of the American Society of Human Genetics, autosomal tests cannot detect "large portions" of DNA from distant ancestors because it has not been inherited.[72]

With the increasing popularity of the use of DNA tests for ethnicity tests, uncertainties and errors in ethnicity estimates are a drawback for Genetic genealogy. While ethnicity estimates at the continental level should be accurate (with the possible exception of East Asia and the Americas), sub-continental estimates, especially in Europe, are often inaccurate. Customers may be misinformed about the uncertainties and errors of the estimates.[73]

Some have recommended government or other regulation of ancestry testing to ensure its performance to an agreed standard.[74]

A number of law enforcement agencies took legal action to compel genetic genealogy companies to release genetic information that could match cold case crime victims[75] or perpetrators. A number of companies fought the requests.[76]

Common misunderstandings of genetics

The popular consciousness of DNA testing and of DNA generally is subject to a number of misconceptions involving the reliability of testing, the nature of the connections with one's ancestors, the connection between DNA and personal traits, etc.[77]

Medical information

Though genealogical DNA tests are not designed mainly for medical purposes, autosomal DNA tests can be used to analyze the probability of hundreds of heritable medical conditions,[78] albeit the result is complex to understand and may confuse a non-expert. 23andMe provides medical and trait information from their genealogical DNA test[79] and for a fee the Promethease web site analyses genealogical DNA test data from Family Tree DNA, 23andMe, or AncestryDNA for medical information.[80] Promethease, and its research paper crawling database SNPedia, has received criticism for technical complexity and a poorly defined "magnitude" scale that causes misconceptions, confusion and panic among its users.[81]

The testing of full MtDNA and YDNA sequences is still somewhat controversial as it may reveal even more medical information. For example, a correlation exists between a lack of Y-DNA marker DYS464 and infertility, and between mtDNA haplogroup H and protection from sepsis. Certain haplogroups have been linked to longevity in some population groups.[82][83] The field of linkage disequilibrium, unequal association of genetic disorders with a certain mitochondrial lineage, is in its infancy, but those mitochondrial mutations that have been linked are searchable in the genome database Mitomap.[84] Family Tree DNA's MtFull Sequence test analyses the full MtDNA genome[26] and the National Human Genome Research Institute operates the Genetic And Rare Disease Information Center[85] that can assist consumers in identifying an appropriate screening test and help locate a nearby medical center that offers such a test.

DNA testing for consumers

The first company to provide direct-to-consumer genealogical DNA tests was the now defunct GeneTree. However, it did not offer multi-generational genealogy tests. In fall 2001, GeneTree sold its assets to Salt Lake City-based Sorenson Molecular Genealogy Foundation (SMGF) which originated in 1999.[86] While in operation, SMGF provided free Y-chromosome and mitochondrial DNA tests to thousands.[87] Later, GeneTree returned to genetic testing for genealogy in conjunction with the Sorenson parent company and eventually was part of the assets acquired in the Ancestry.com buyout of SMGF in 2012.[88][89]

In 2000, Family Tree DNA, founded by Bennett Greenspan and Max Blankfeld, was the first company dedicated to direct-to-consumer testing for genealogy research. They initially offered eleven-marker Y-Chromosome STR tests and HVR1 mitochondrial DNA tests. They originally tested in partnership with the University of Arizona.[90][91] [92][93] [94]

In 2007, 23andMe was the first company to offer a saliva-based direct-to-consumer genetic testing.[95] It was also the first to implement the use of autosomal DNA for ancestry testing, which other major companies (e.g., Ancestry, Family Tree DNA, and MyHeritage) now use.[96][97]

MyHeritage launched its genetic testing service in 2016, allowing users to use cheek swabs to collect samples.[98] In 2019, new analysis tools were presented: autoclusters (grouping all matches visually into clusters)[99] and family tree theories (suggesting conceivable relations between DNA matches by combining several Myheritage trees as well as the Geni global family tree).[100]

Living DNA, founded in 2015, also provides a genetic testing service. Living DNA uses SNP chips to provide reports on autosomal ancestry, Y, and mtDNA ancestry.[101][102] Living DNA provides detailed reports on ancestry from the UK as well as detailed Y chromosome and mtDNA reports.[103][104][105]

In 2019 it was estimated that large genealogical testing companies had about 26 million DNA profiles.[106][107] Many transferred their test result for free to multiple testing sites, and also to genealogical services such as Geni.com and GEDmatch. GEDmatch said in 2018 that about half of their one million profiles were from the USA.[107]

DNA in genealogy software

Some genealogy software programs – such as Family Tree Maker, Legacy Family Tree (Deluxe Edition) and the Swedish program Genney – allow recording DNA marker test results. This allows for tracking of both Y-chromosome and mtDNA tests, and recording results for relatives.[108]

See also

- 23andMe

- Ancestry.com

- Archaeogenetics

- Common misunderstandings of genetics

- DNA paternity testing

- Electropherogram

- Family name (patrilineal surname)

- Family Tree DNA

- Genetic fingerprinting

- Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act

- Genographic Project (Geno 2.0 Next Generation)

- International HapMap Project

- International Society of Genetic Genealogy

- List of DNA tested mummies

- Living DNA

- MyHeritage

References

- ↑ Bettinger & Wayne (2016, p. 8)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Understanding genetic ancestry testing". Molecular and Cultural Evolution Lab. University College London. 2016. Archived from the original on 7 April 2016. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- ↑ "Claims of connections, therefore, between specific uniparental lineages and historical figures or historical migrations of peoples are merely speculative." Royal, Charmaine D.; Novembre, John; Fullerton, Stephanie M.; Goldstein, David B.; Long, Jeffrey C.; Bamshad, Michael J.; Clark, Andrew G. (14 May 2010). "Inferring Genetic Ancestry: Opportunities, Challenges, and Implications". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 86 (5): 661–73. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.03.011. ISSN 0002-9297. PMC 2869013. PMID 20466090.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Emery, Leslie S.; Magnaye, Kevin M.; Bigham, Abigail W.; Akey, Joshua M.; Bamshad, Michael J. (5 February 2015). "Estimates of Continental Ancestry Vary Widely among Individuals with the Same mtDNA Haplogroup". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 96 (2): 183–93. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.12.015. ISSN 0002-9297. PMC 4320259. PMID 25620206.

- ↑ Bettinger & Wayne (2016, p. 70)

- ↑ Bettinger & Wayne (2016, p. 68)

- ↑ "Autosomal DNA – ISOGG Wiki". isogg.org. Retrieved 3 February 2017.

- ↑ "Best Ancestry DNA Test 2018 – Which Testing Kit is Best & How to Choose". 10 January 2018.

- ↑ "Concepts – Imputation". 5 September 2017.

- ↑ "March – 2016 – DNAeXplained – Genetic Genealogy". dna-explained.com. 30 March 2016.

- ↑ "The Danger of Distant Matches – The Genetic Genealogist". 6 January 2017.

- ↑ "Cousin statistics – ISOGG Wiki". isogg.org.

- ↑ Combs-Bennett, Shannon (3 December 2015). "How to Use AncestryDNA Shared Matches – Family Tree". Family Tree. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- ↑ Lassalle, Melody (15 March 2018). "MyHeritage DNA Ups Its Game with Updated Chromosome Browser". Genealogy Research Journal. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- ↑ Southard, Diahan (19 June 2017). "Triple Play: Triangulating Your DNA Matches – Family Tree". Family Tree. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- ↑ Bettinger & Wayne (2016, p. 107)

- ↑ Bettinger & Wayne (2016, p. 114)

- ↑ Bettinger & Wayne (2016, p. 111)

- 1 2 Westen, Antoinette A.; Kraaijenbrink, Thirsa; Robles de Medina, Elizaveta A.; Harteveld, Joyce; Willemse, Patricia; Zuniga, Sofia B.; van der Gaag, Kristiaan J.; Weiler, Natalie E.C.; Warnaar, Jeroen (May 2014). "Comparing six commercial autosomal STR kits in a large Dutch population sample". Forensic Science International: Genetics. 10: 55–63. doi:10.1016/j.fsigen.2014.01.008. PMID 24680126.

- ↑ Ziętkiewicz, Ewa; Witt, Magdalena; Daca, Patrycja; Żebracka-Gala, Jadwiga; Goniewicz, Mariusz; Jarząb, Barbara; Witt, Michał (15 December 2011). "Current genetic methodologies in the identification of disaster victims and in forensic analysis". Journal of Applied Genetics. 53 (1): 41–60. doi:10.1007/s13353-011-0068-7. ISSN 1234-1983. PMC 3265735. PMID 22002120.

- ↑ Sun, Hao; Zhou, Chi; Huang, Xiaoqin; Lin, Keqin; Shi, Lei; Yu, Liang; Liu, Shuyuan; Chu, Jiayou; Yang, Zhaoqing (8 April 2013). Caramelli, David (ed.). "Autosomal STRs Provide Genetic Evidence for the Hypothesis That Tai People Originate from Southern China". PLOS ONE. 8 (4): e60822. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...860822S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0060822. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3620166. PMID 23593317.

- ↑ Guo, Yuxin; Chen, Chong; Xie, Tong; Cui, Wei; Meng, Haotian; Jin, Xiaoye; Zhu, Bofeng (13 June 2018). "Forensic efficiency estimate and phylogenetic analysis for Chinese Kyrgyz ethnic group revealed by a panel of 21 short tandem repeats". Royal Society Open Science. 5 (6): 172089. Bibcode:2018RSOS....572089G. doi:10.1098/rsos.172089. ISSN 2054-5703. PMC 6030347. PMID 30110484.

- ↑ Norrgard, Karen (2008). "Forensics, DNA Fingerprinting, and CODIS". Nature Education. 1 (1): 35.

- ↑ Bettinger & Wayne (2016, p. 9)

- ↑ "mtDNA regions". Phylotree.org. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- 1 2 "Family Tree DNA Review". Top 10 DNA Tests. May 2018. Retrieved 19 May 2018.

- ↑ Bettinger & Wayne (2016, p. 50)

- ↑ Poznik GD, Henn BM, Yee MC, Sliwerska E, Euskirchen GM, Lin AA, Snyder M, Quintana-Murci L, Kidd JM, Underhill PA, Bustamante CD (August 2013). "Sequencing Y chromosomes resolves discrepancy in time to common ancestor of males versus females". Science. 341 (6145): 562–65. Bibcode:2013Sci...341..562P. doi:10.1126/science.1237619. PMC 4032117. PMID 23908239.

- ↑ Fu Q, Mittnik A, Johnson PL, Bos K, Lari M, Bollongino R, Sun C, Giemsch L, Schmitz R, Burger J, Ronchitelli AM, Martini F, Cremonesi RG, Svoboda J, Bauer P, Caramelli D, Castellano S, Reich D, Pääbo S, Krause J (21 March 2013). "A revised timescale for human evolution based on ancient mitochondrial genomes". Current Biology. 23 (7): 553–59. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2013.02.044. PMC 5036973. PMID 23523248.

- ↑ Bettinger & Wayne (2016, p. 51)

- ↑ Bettinger & Wayne (2016, p. 30)

- ↑ "Matching Y-Chromosome DNA Results". Molecular Genealogy. Sorenson Molecular Genealogy Foundation. Archived from the original on 3 May 2015. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- ↑ Bettinger & Wayne (2016, p. 35)

- ↑ Bettinger & Wayne (2016, p. 41)

- ↑ Karmin; et al. (2015). "A recent bottleneck of Y chromosome diversity coincides with a global change in culture". Genome Research. 25 (4): 459–66. doi:10.1101/gr.186684.114. PMC 4381518. PMID 25770088. "we date the Y-chromosomal most recent common ancestor (MRCA) in Africa at 254 (95% CI 192–307) kya and detect a cluster of major non-African founder haplogroups in a narrow time interval at 47–52 kya, consistent with a rapid initial colonization model of Eurasia and Oceania after the out-of-Africa bottleneck. In contrast to demographic reconstructions based on mtDNA, we infer a second strong bottleneck in Y-chromosome lineages dating to the last 10 ky."

- ↑ Mendez, L.; et al. (2016). "The Divergence of Neandertal and Modern Human Y Chromosomes". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 98 (4): 728–34. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.02.023. PMC 4833433. PMID 27058445.

- ↑ Bettinger & Wayne (2016, p. 40)

- ↑ Alsup, Blake (29 April 2019). "Ancestry.com update changes ethnicity of customers". NY Daily News.

- ↑ Daalder, Marc (18 September 2018). "Ancestry.com changed how it determines ethnicity and people are upset". K5 News.

- ↑ "mtDNA matches". Smgf.org. Archived from the original on 18 November 2008. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- 1 2 Sykes, Bryan (2001). The Seven Daughters of Eve. W. W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-02018-5, pp. 291–92. Sykes discusses the difficulty in genealogically tracing a maternal lineage, due to the lack of matrilineal surnames (or matrinames).

- ↑ Rutherford, Adam (24 May 2015). "So you're related to Charlemagne? You and every other living European…". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ↑ "Patriclan: Trace Your Paternal Ancestry". African Ancestry. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- ↑ Paul Heinegg, Free African Americans of Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Maryland and Delaware, accessed 15 February 2008

- ↑ Paul Heinegg, Free African Americans of Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Maryland and Delaware, accessed 15 February 2008

- ↑ "Native American | Definition of Native American by Merriam-Webster". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ↑ "AncestryDNA FAQ". www.ancestry.co.uk.

- ↑ Hammer MF, Behar DM, Karafet TM, Mendez FL, Hallmark B, Erez T, Zhivotovsky LA, Rosset S, Skorecki K (November 2009). "Extended Y chromosome haplotypes resolve multiple and unique lineages of the Jewish priesthood". Human Genetics. 126 (5): 707–17. doi:10.1007/s00439-009-0727-5. PMC 2771134. PMID 19669163.

- ↑ Mas, V. (2013). Y-DNA Haplogroup J1 phylogenetic tree. Figshare. doi:10.6084/m9.figshare.741212.

- ↑ ftdna.com (kept uptodate). http://www.familytreedna.com/faq/answers/default.aspx?faqid=9#922 "FAQ: ...how should the genetic distance at 37 Y-chromosome STR markers be interpreted?" Retrieved 2012-01-13.

- ↑ ftdna.com (kept uptodate). http://www.familytreedna.com/faq/answers/default.aspx?faqid=9#925 "FAQ: ...how should the genetic distance at 111 Y-chromosome STR markers be interpreted?" Retrieved 2012-01-13.

- ↑ Randall, Caresa Alexander (16 November 2016). "Adopted man finds biological family with help of AncestryDNA". Deseret News. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- ↑ ""Buckskin Girl" case: DNA breakthrough leads to ID of 1981 murder victim". CBS News. 12 March 2018. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- ↑ Augenstein, Seth (9 May 2018). "DNA Doe Project IDs 2001 Motel Suicide, Using Genealogy". Forensic Magazine. Retrieved 19 May 2018.

- ↑ Zhang, Sarah (27 March 2018). "How a Genealogy Website Led to the Alleged Golden State Killer". The Atlantic. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- ↑ Green, Sara Jean (18 May 2018). "Investigators use DNA, genealogy database to ID suspect in 1987 double homicide". The Seattle Times. Retrieved 19 May 2018.

- ↑ Regalado, Antonio. "Investigators searched a million people's DNA to find Golden State serial killer".

- ↑ Lillis, Ryan; Kasler, Dale; Chabria, Anita (27 April 2018). "'Open-source' genealogy site provided missing DNA link to East Area Rapist, investigator says". The Sacramento Bee. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ↑ Zhang, Sarah (19 May 2018). "The Coming Wave of Murders Solved by Genealogy". The Atlantic. Retrieved 19 May 2018.

- ↑ Haag, Matthew (4 February 2019). "FamilyTreeDNA Admits to Sharing Genetic Data With F.B.I." The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- ↑ Augenstein, Seth (23 May 2019). "Forensic Genealogy: Where Does Cold-Case Breakthrough Technique Go After GEDmatch Announcement?". Forensic Magazine. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- ↑ Augenstein, Seth (24 May 2018). "Golden State Killer Backlash? Public Databases Shutting Down in Wake of Arrest". Forensic Magazine. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- ↑ Vergano, Dan (13 June 2013). "DNA detectives seek origins of you". USA Today. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ↑ Estes, Roberta (30 December 2015). "23andMe, Ancestry and Selling Your DNA Information". DNAeXplained – Genetic Genealogy. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ↑ Seife, Charles (27 November 2013). "23andMe Is Terrifying, but Not for the Reasons the FDA Thinks; The genetic-testing company's real goal is to hoard your personal data". Scientific American. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ↑ Wallace SE, Gourna EG, Nikolova V, Sheehan NA (December 2015). "Family tree and ancestry inference: is there a need for a 'generational' consent?". BMC Medical Ethics. 16 (1): 87. doi:10.1186/s12910-015-0080-2. PMC 4673846. PMID 26645273.

- ↑ Collins, Nick (17 March 2013). "DNA ancestry tests branded 'meaningless'". The Telegraph. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ↑ Thomas, Mark (25 February 2013). "To claim someone has 'Viking ancestors' is no better than astrology". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ↑ Reference (22 November 2016). "What is genetic ancestry testing?". Genetics Home Reference. U.S National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- ↑ "DNA doesn't lie!". 1 October 2017.

- ↑ "Non-paternity event – ISOGG Wiki". isogg.org.

- ↑ Harmon, Katherine (14 May 2010). "Genetic ancestry testing is an inexact science, task force says". Scientific American. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ↑ Estes, Roberta (11 January 2017). "Concepts – Calculating Ethnicity Percentages". DNAeXplained - Genetic Genealogy.

- ↑ Lee SS, Soo-Jin Lee S, Bolnick DA, Duster T, Ossorio P, Tallbear K (July 2009). "Genetics. The illusive gold standard in genetic ancestry testing". Science. 325 (5936): 38–39. doi:10.1126/science.1173038. PMID 19574373. S2CID 206519537.

- ↑ O'Rourke, Ciara (16 August 2017). "Solving a Murder Mystery With Ancestry Websites". The Atlantic.

- ↑ Robbins, Rebecca (28 April 2018). "The Golden State Killer Case Was Cracked with a Genealogy Web Site". Scientific American / STAT. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- ↑ Zimmer, Carl (2019). "Seven Big Misconceptions about Heredity". Skeptical Inquirer. 43 (3): 34–39. Archived from the original on 8 August 2019. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- ↑ "List of medical conditions – SNPedia". www.snpedia.com. Retrieved 27 June 2019.

- ↑ "The Pros and Cons of the Main Autosomal DNA Testing Companies". The DNA Geek. 14 November 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2018.

- ↑ Bettinger, Blaine (22 September 2013). "What Else Can I Do with My DNA Test Results?". The Genetic Genealogist. Retrieved 19 May 2018.

- ↑ Arthur, Rob (20 January 2016). "What's in Your Genes? Some Companies Analyzing Your DNA Use Junk Science". Slate.

- ↑ De Benedictis G, Rose G, Carrieri G, De Luca M, Falcone E, Passarino G, Bonafe M, Monti D, Baggio G, Bertolini S, Mari D, Mattace R, Franceschi C (September 1999). "Mitochondrial DNA inherited variants are associated with successful aging and longevity in humans". FASEB Journal. 13 (12): 1532–36. doi:10.1096/fasebj.13.12.1532. PMID 10463944. S2CID 8699708.

- ↑ Rose, Giuseppina; Passarino, Giuseppe; Carrieri, Giuseppina; Altomare, Katia; Greco, Valentina; Bertolini, Stefano; Bonafè, Massimiliano; Franceschi, Claudio; De Benedictis, Giovanna (September 2001). "European Journal of Human Genetics (2001) 9, pp 701±707" (PDF). European Journal of Human Genetics. 9 (9): 701–707. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200703. PMID 11571560. S2CID 13730557.

- ↑ "Mitomap". Mitomap. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- ↑ "Genetic And Rare Disease Information Center (GARD)". Genome.gov. 22 March 2011. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- ↑ "CMMG alum launches multi-million dollar genetic testing company" (PDF). Alum Notes. Wayne State University School of Medicine. 17 (2): 1. Spring 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2013.

- ↑ "How Big Is the Genetic Genealogy Market?". The Genetic Genealogist. 6 November 2007. Retrieved 19 February 2009.

- ↑ Dobush, Grace (12 July 2012). "Ancestry.com Acquisition Means Changes at GeneTree and SMGF.org". Family Tree. Archived from the original on 10 April 2019. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- ↑ "Ancestry.com Launches new AncestryDNA Service: The Next Generation of DNA Science Poised to Enrich Family History Research" (Press release). Archived from the original on 26 May 2013. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- ↑ Belli, Anne (18 January 2005). "Moneymakers: Bennett Greenspan". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

Years of researching his family tree through records and documents revealed roots in Argentina, but he ran out of leads looking for his maternal great-grandfather. After hearing about new genetic testing at the University of Arizona, he persuaded a scientist there to test DNA samples from a known cousin in California and a suspected distant cousin in Buenos Aires. It was a match. But the real find was the idea for Family Tree DNA, which the former film salesman launched in early 2000 to provide the same kind of service for others searching for their ancestors.

- ↑ "The Science of Molecular Genealogy". National Genealogical Society Quarterly. National Genealogical Society. 93 (1–4): 248. 2005.

Businessman Bennett Greenspan hoped that the approach used in the Jefferson and Cohen research would help family historians. After reaching a brick wall on his mother's surname, Nitz, he discovered and Argentine researching the same surname. Greenspan enlisted the help of a male Nitz cousin. A scientist involved in the original Cohen investigation tested the Argentine's and Greenspan's cousin's Y chromosomes. Their haplotypes matched perfectly.

- ↑ Lomax, John Nova (14 April 2005). "Who's Your Daddy?". Houston Press. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

A real estate developer and entrepreneur, Greenspan has been interested in genealogy since his preteen days.

- ↑ Dardashti, Schelly Talalay (30 March 2008). "When oral history meets genetics". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

Greenspan, born and raised in Omaha, Nebraska, has been interested in genealogy from a very young age; he drew his first family tree at age 11.

- ↑ Bradford, Nicole (24 February 2008). "Riding the 'genetic revolution'". Houston Business Journal. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- ↑ Hamilton, Anita (29 October 2008). "Best Inventions of 2008". Time. Archived from the original on 2 November 2008. Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- ↑ "About Us". 23andMe. Archived from the original on 26 February 2018. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ↑ Janzen, Tim; et al. "Family Tree DNA Learning Center". Autosomal DNA testing comparison chart. Gene by Gene.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ↑ Lardinois, Frederic (7 November 2016). "MyHeritage launches DNA testing service to help you uncover your family's history". TechCrunch. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ↑ "Introducing AutoClusters for DNA Matches". MyHeritage Blog. 28 February 2019.

- ↑ "MyHeritage's "Theory of Family Relativity": An Exciting New Tool!". DanaLeeds.com. 15 March 2019.

- ↑ "Living DNA review". 21 June 2019.

- ↑ "Is this the most detailed at-home DNA testing kit yet?". CNN. 22 April 2019.

- ↑ Durie, Bruce (January 2012). Scottish Genealogy (Fourth ed.). The History Press. ISBN 9780752488479.

- ↑ "Comparing the 5 Major DNA Tests: Living DNA - Family Tree". www.familytreemagazine.com. Archived from the original on 2 August 2018.

- ↑ "What I actually learned about my family after trying 5 DNA ancestry tests". 13 June 2018.

- ↑ Regalado, Antonio (11 February 2019). "More than 26 million people have taken an at-home ancestry test". MIT Technology Review. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- 1 2 Michaeli, Yarden (16 November 2018). "To Solve Cold Cases, All It Takes Is Crime Scene DNA, a Genealogy Site and High-speed Internet". Haaretz. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- ↑ Bettinger, Blaine (22 September 2013). "What Else Can I Do with My DNA Test Results?". The Genetic Genealogist. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

Sources

- Bettinger BT, Wayne DP (2016). Genetic Genealogy in Practice. Arlington, VA: National Genealogical Society. ISBN 978-1-935815-22-8.

Further reading

- Smolenyak M, Turner A (12 October 2004). Trace your roots with DNA: using genetic tests to explore your family tree. Rodale. ISBN 978-1-59486-006-5.

- Pomery C, Jones S (1 October 2004). DNA and family history: how genetic testing can advance your genealogical research. Dundurn Press Ltd. ISBN 978-1-55002-536-1.