| Content | |

|---|---|

| Description | Encyclopædia of genes and gene variants |

| Data types captured | All gene features in Human & mouse genome |

| Contact | |

| Research center | Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute |

| Authors | Harrow J, et al [1] |

| Primary citation | PMID 22955987 |

| Release date | September 2012 |

| Access | |

| Website | Website Gencode |

| Tools | |

| Web | UCSC Genome Browser: http://genome.cse.ucsc.edu/encode/ |

| Miscellaneous | |

| License | Open Access |

| Data release frequency | Human - Quarterly Mouse - Half yearly |

| Version | Human - Release 37 (February 2021) Mouse - Release M26 (February 2021) |

GENCODE is a scientific project in genome research and part of the ENCODE (ENCyclopedia Of DNA Elements) scale-up project.

The GENCODE consortium was initially formed as part of the pilot phase of the ENCODE project to identify and map all protein-coding genes within the ENCODE regions (approx. 1% of Human genome).[2] Given the initial success of the project, GENCODE now aims to build an “Encyclopedia of genes and genes variants”.[2]

The result will be a set of annotations including all protein-coding loci with alternatively transcribed variants,[3] non-coding loci[4] with transcript evidence, and pseudogenes.[5]

Current progress

GENCODE is currently progressing towards its goals in Phase 2 of the project.[6]

The most recent release of the Human geneset annotations is Gencode 36, with a freeze date of December 2020. This release utilises the latest GRCh38 human reference genome assembly.[7]

The latest release for the mouse geneset annotations is Gencode M25, also with a freeze date December 2020.[7]

Since September 2009, GENCODE has been the human gene set used by the Ensembl project and each new GENCODE release corresponds to an Ensembl release.[8]

History

2003 September

The project was designed with three phases - Pilot, Technology development and Production phase.[9] The pilot stage of the ENCODE project aimed to investigate in great depth, computationally and experimentally, 44 regions totaling 30 Mb of sequence representing approximately 1% of the human genome. As part of this stage, the GENCODE consortium was formed to identify and map all protein-coding genes within the ENCODE regions.[2] It was envisaged that the results of the first two phases will be used to determine the best path forward for analysing the remaining 99% of the human genome in a cost-effective and comprehensive production phase.[9]

2005 April

The first release of the annotation of the 44 ENCODE regions was frozen on 29 April 2005 and was used in the first ENCODE Genome Annotation Assessment Project (E-GASP) workshop.[2] GENCODE Release 1 contained 416 known loci, 26 novel (coding DNA sequence) CDS loci, 82 novel transcript loci, 78 putative loci, 104 processed pseudogenes and 66 unprocessed pseudogenes.

2005 October

A second version (release 02) was frozen on 14 October 2005, containing updates following discoveries from experimental validations using RACE and RT-PCR techniques.[2] GENCODE Release 2 contained 411 known loci, 30 novel CDS loci, 81 novel transcript loci, 83 putative loci, 104 processed pseudogenes and 66 unprocessed pseudogenes.

2007 June

The conclusions from the pilot project were published in June 2007.[10] The findings highlighted the success of the pilot project to create a feasible platform and new technologies to characterise functional elements in the human genome, which paves the way for opening research into genome-wide studies.

2007 October

New funding was part of NHGRI's endeavour to scale-up the ENCODE Project to a production phase on the entire genome along with additional pilot-scale studies.

2012 September

In September 2012, The GENCODE consortium published a major paper discussing the results from a major release – GENCODE Release 7, which was frozen in December 2011.[11]

2018

In 2018, one of the latest additions to the GENCODE project was the CRISPR/Cas9 track on human and model organism assemblies. CRISPR is a genome editing technique that uses sequences of RNA that successfully bind to the region edited with high specificity. The new track was designed to assist in the search for appropriate guide sentences by listing potential binding sites for the CRISPR/Cas9 complex that are next to transcribed regions, or within 200 bp of one. For each site, the track provides possible guide sequences along with a collection of predicted efficiency and specificity scores for those guide sequences. It also provides information about potential off-targets, grouped by the number of missmatches between the off-target and the guide.[11]

2020

Among other achievements, it has been completed the first pass manual annotation of the mouse reference genome, it has started a cooperation with RefSeq and Uniprot reference annotation databases toward achieving annotation convergence, and the annotation of lncRNAs has been improved via the discovery of novel loci and novel transcripts at existing loci. Also, given the COVID-19 pandemic during 2020, there has been an urge to support research responding to the situation, so GENCODE has reviewed and improved the annotation for a set of protein-coding genes associated with SARSCoV-2 infection.[12]

Key Participants

The key participants of the GENCODE project have remained relatively consistent throughout its various phases, with the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute now leading the overall efforts of the project.

A summary of key participating institutions of each phase is listed below:[6][13]

| GENCODE Phase 2 (Current) | GENCODE Scale-up Phase | GENCODE Pilot Phase | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wellcome Sanger Institute, Cambridge, UK | Wellcome Sanger Institute, Cambridge, UK | Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Cambridge, UK

| |

| Centre de Regulació Genòmica, Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain | Centre de Regulació Genòmica, Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain | Institut Municipal d'Investigació Mèdica (IMIM), Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain | |

| University of Lausanne, Switzerland | University of Lausanne, Switzerland | University of Geneva, Switzerland | |

| University of California, Santa Cruz, California, USA | University of California, Santa Cruz, USA | Washington University in St. Louis, USA | |

| Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Boston, USA | Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Boston, USA | University of California, Berkeley, USA | |

| Yale University, New Haven, USA | Yale University, New Haven, USA | European Bioinformatics Institute, Hinxton, UK | |

| Spanish National Cancer Research Centre (CNIO), Madrid, Spain | Spanish National Cancer Research Centre, Madrid, Spain | ||

| Washington University in St. Louis, USA |

Participants, PIs and CO-PIs

Source:[8]

- Paul Flicek (Lead PI), EMBL European Bioinformatics Institute, Cambridge, UK

- Roderic Guigo (PI), Centre de Regulació Genòmica (CRG), Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain

- Manolis Kellis (PI), Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Boston, USA

- Mark B. Gerstein (PI), Yale University, New Haven, USA

- Benedict Paten (PI), University of California, Santa Cruz, California, USA

- Michael Tress, Spanish National Cancer Research Centre (CNIO), Madrid, Spain

- Jyoti Choudhary, Institute of Cancer Research (ICR), London, UK

Key Statistics

Since its inception, GENCODE has released 36 versions of the Human gene set annotations (excluding minor updates).

The key summary statistics of the most recent GENCODE Human gene set annotation (Release 36, December 2020 freeze) is shown below:[14]

| Categories | Total | Categories | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total No of Genes | 60,660 | Total No of Transcripts | 232,117 |

| Protein-coding genes | 19,962 | Protein-coding transcripts | 85,269 |

| Long non-coding RNA genes | 17,958 | - full length protein-coding: | 59,269 |

| Small non-coding RNA genes | 7,569 | - partial length protein-coding: | 26,000 |

| Pseudogenes | 14,761 | Nonsense mediated decay transcripts | 17,378 |

| - processed pseudogenes: | 10,669 | Long non-coding RNA loci transcripts | 48,734 |

| - unprocessed pseudogenes: | 3,554 | ||

| - unitary pseudogenes: | 236 | ||

| - polymorphic pseudogenes: | 48 | ||

| - pseudogenes: | 18 | ||

| Immunoglobulin/T-cell receptor gene segments | 645 | Total No of distinct translations | 63,058 |

| - protein coding segments: | 409 | Genes that have more than one distinct translations | 13,685 |

| - pseudogenes: | 236 |

Through advancements in sequencing technologies (such as RT-PCR-seq), increased coverage from manual annotations (HAVANA group), and improvements to automatic annotation algorithms using Ensembl, the accuracy and completeness of GENCODE annotations have been continuously refined through its iteration of releases.

A comparison of key statistics from 3 major GENCODE releases until 2014 is shown below.[14] It is evident that although the coverage, in terms of total number of genes discovered, is steady increasing, the number of protein-coding genes has actually decreased. This is mostly attributed to new experimental evidence obtained using Cap Analysis Gene Expression (CAGE) clusters, annotated PolyA sites, and peptide hits.[11]

- Version 7 (December 2010 freeze, GRCh37) - Ensembl 62

- Version 10 (July 2011 freeze, GRCh37) - Ensembl 65

- Version 20 (April 2014 freeze, GRCh38) - Ensembl 76

.PNG.webp) Comparison of GENCODE Human versions (Transcripts)

Comparison of GENCODE Human versions (Transcripts).PNG.webp) Comparison of GENCODE Human versions (Genes)

Comparison of GENCODE Human versions (Genes).PNG.webp) Comparison of GENCODE Human versions (Translations)

Comparison of GENCODE Human versions (Translations)

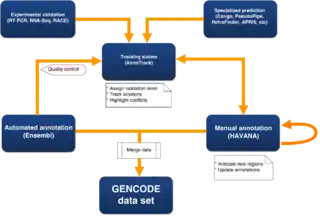

Methodology

Putative loci can be verified by wet-lab experiments and computational predictions are analysed manually.[15] Currently, to ensure a set of annotation covers the complete genome rather than just the regions that have been manually annotated, a merged data set is created using manual annotations from HAVANA, together with automatic annotations from the Ensembl automatically annotated gene set. This process also adds unique full-length CDS predictions from the Ensembl protein coding set into manually annotated genes, to provide the most complete and up-to-date annotation of the genome possible.[16]

Automatic annotation (Ensembl)

Ensembl transcripts are products of the Ensembl automatic gene annotation system (a collection of gene annotation pipelines), termed the Ensembl gene build. All Ensembl transcripts are based on experimental evidence and thus the automated pipeline relies on the mRNAs and protein sequences deposited into public databases from the scientific community.[17]

Manual Annotation (HAVANA group)

There are several analysis groups in the GENCODE consortium that run pipelines that aid the manual annotators in producing models in unannotated regions, and to identify potential missed or incorrect manual annotation, including completely missing loci, missing alternative isoforms, incorrect splice sites and incorrect biotypes. These are fed back to the manual annotators using the AnnoTrack tracking system.[18] Some of these pipelines use data from other ENCODE subgroups including RNASeq data, histone modification and CAGE and Ditag data. RNAseq data is an important new source of evidence, but generating complete gene models from it is a difficult problem. As part of GENCODE, a competition was run to assess the quality of predictions produced by various RNAseq prediction pipelines (Refer to RGASP below). To confirm uncertain models, GENCODE also has an experimental validation pipeline using RNA sequencing and RACE.[16]

Assessing quality

For GENCODE 7, transcript models are assigned a high or low level of support based on a new method developed to score the quality of transcripts.[2]

Usage/Access

The current GENCODE Human gene set version (GENCODE Release 20) includes annotation files (in GTF and GFF3 formats), FASTA files and METADATA files associated with the GENCODE annotation on all genomic regions (reference-chromosomes/patches/scaffolds/haplotypes). The annotation data is referred on reference chromosomes and stored in separated files which include: Gene annotation, PolyA features annotated by HAVANA, (Retrotransposed) pseudogenes predicted by the Yale & UCSC pipelines, but not by HAVANA, long non-coding RNAs, and tRNA structures predicted by tRNA-Scan. Some examples of the lines in the GTF format are shown below:

The columns within the GENCODE GTF file formats are described below.

Format description of GENCODE GTF file. TAB-separated standard GTF columns

| Column number | Content | Values/format |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | chromosome name | chr{1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,X,Y,M} |

| 2 | annotation source | {ENSEMBL,HAVANA} |

| 3 | feature-type | {gene,transcript,exon,CDS,UTR,start_codon,stop_codon,Selenocysteine} |

| 4 | genomic start location | integer-value (1-based) |

| 5 | genomic end location | integer-value |

| 6 | score (not used) | . |

| 7 | genomic strand | {+,-} |

| 8 | genomic phase (for CDS features) | {0,1,2,.} |

| 9 | additional information as key-value pairs | See explanation in table below. |

Description of key-value pairs in 9th column of the GENCODE GTF file (format: key "value")

| Key name | Value format |

|---|---|

| gene_id | ENSGXXXXXXXXXXX |

| transcript_id | ENSTXXXXXXXXXXX |

| gene_type | list of biotypes |

| gene_status | {KNOWN,NOVEL,PUTATIVE} |

| gene_name | string |

| transcript_type | list of biotypes |

| transcript_status | {KNOWN,NOVEL,PUTATIVE} |

| transcript_name | string |

| exon_number | indicates the biological position of the exon in the transcript |

| exon_id | ENSEXXXXXXXXXXX |

| level |

|

Biodalliance Genome Browser

Also, the GENCODE website contains a Genome Browser for human and mouse where you can reach any genomic region by giving the chromosome number and start-end position (e.g. 22:30,700,000..30,900,000), as well as by ENS transcript id (with/without version), ENS gene id (with/without version) and gene name. The browser is powered by Biodalliance.[19]

Challenges

Definition of a "gene"

The definition of a "gene" has never been a trivial issue, with numerous definitions and notions proposed throughout the years since the discovery of the human genome. First, genes were conceived in the 1900s as discrete units of heredity, then it was thought as the blueprint for protein synthesis, and in more recent times, it was being defined as genetic code that is transcribed into RNA. Although the definition of a gene has evolved greatly over the last century, it has remained a challenging and controversial subject for many researchers. With the advent of the ENCODE/GENCODE project, even more problematic aspects of the definition have been uncovered, including alternative splicing (where a series of exons are separated by introns), intergenic transcriptions, and the complex patterns of dispersed regulation, together with non-genic conservation and the abundance of noncoding RNA genes. As GENCODE endeavours to build an encyclopaedia of genes and gene variants, these problems presented a mounting challenge for the GENCODE project to come up with an updated notion of a gene.[20]

Human Genome Project

The Human Genome Project was an international research effort to determine the sequence of the human genome and identify the genes that it contains. The Project was coordinated by the National Institutes of Health and the U.S. Department of Energy. Additional contributors included universities across the United States and international partners in the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Japan, and China. The Human Genome Project formally began in 1990 and was completed in 2003, 2 years ahead of its original schedule.[21]

Sub Projects

Ensembl

lncRNA Expression Microarray Design

A key research area of the GENCODE project was to investigate the biological significance of long non-coding RNAs (lncRNA). To better understand the lncRNA expression in Humans, a sub project was created by GENCODE to develop custom microarray platforms capable of quantifying the transcripts in the GENCODE lncRNA annotation.[4] A number of designs have been created using the Agilent Technologies eArray system, and these designs are available in a standard custom Agilent format.[4]

RGASP

The RNA-seq Genome Annotation Assessment Project (RGASP) project is designed to assess the effectiveness of various computational methods for high quality RNA-sequence data analysis. The primary goals of RGASP are to provide an unbiased evaluation for RNA-seq alignment, transcript characterisation (discovery, reconstruction and quantification) software, and to determine the feasibility of automated genome annotations based on transcriptome sequencing.[23]

RGASP is organised in a consortium framework modelled after the EGASP (ENCODE Genome Annotation Assessment Project) gene prediction workshop, and two rounds of workshops have been conducted to address different aspects of RNA-seq analysis as well as changing sequencing technologies and formats. One of the main discoveries from rounds 1 & 2 of the project was the importance of read alignment on the quality of gene predictions produced. Hence, a third round of RGASP workshop is currently being conducted (in 2014) to focus primarily on read mapping to the genome.[23]

See also

References

- ↑ Harrow J, Frankish A, Gonzalez JM, Tapanari E, Diekhans M, Kokocinski F, et al. (September 2012). "GENCODE: the reference human genome annotation for The ENCODE Project" (PDF). Genome Research. 22 (9): 1760–74. doi:10.1101/gr.135350.111. PMC 3431492. PMID 22955987.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Harrow J, Denoeud F, Frankish A, Reymond A, Chen CK, Chrast J, et al. (2006). "GENCODE: producing a reference annotation for ENCODE". Genome Biology. 7 (Suppl 1): S4.1–9. doi:10.1186/gb-2006-7-s1-s4. PMC 1810553. PMID 16925838.

- ↑ Frankish A, Mudge JM, Thomas M, Harrow J (2012). "The importance of identifying alternative splicing in vertebrate genome annotation". Database. 2012: bas014. doi:10.1093/database/bas014. PMC 3308168. PMID 22434846.

- 1 2 3 Derrien T, Johnson R, Bussotti G, Tanzer A, Djebali S, Tilgner H, et al. (September 2012). "The GENCODE v7 catalog of human long noncoding RNAs: analysis of their gene structure, evolution, and expression". Genome Research. 22 (9): 1775–89. doi:10.1101/gr.132159.111. PMC 3431493. PMID 22955988.

- ↑ Pei B, Sisu C, Frankish A, Howald C, Habegger L, Mu XJ, et al. (September 2012). "The GENCODE pseudogene resource". Genome Biology. 13 (9): R51. doi:10.1186/gb-2012-13-9-r51. PMC 3491395. PMID 22951037.

- 1 2 "GENCODE - Homepage". 20 December 2020.

- 1 2 "GENCODE – Data". GENCODE. Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute. September 2019. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- 1 2 "GENCODE". Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute. p. The GENCODE Project: Encyclopædia of genes and gene variants. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- 1 2 The ENCODE Project Consortium (October 2004). "The ENCODE (ENCyclopedia Of DNA Elements) Project". Science. 306 (5696): 636–40. Bibcode:2004Sci...306..636E. doi:10.1126/science.1105136. PMID 15499007. S2CID 22837649.

- ↑ Birney E, Stamatoyannopoulos JA, Dutta A, Guigó R, Gingeras TR, Margulies EH, et al. (June 2007). "Identification and analysis of functional elements in 1% of the human genome by the ENCODE pilot project". Nature. 447 (7146): 799–816. Bibcode:2007Natur.447..799B. doi:10.1038/nature05874. PMC 2212820. PMID 17571346.

- 1 2 3 Casper J, Zweig AS, Villarreal C, Tyner C, Speir ML, Rosenbloom KR, et al. (January 2018). "The UCSC Genome Browser database: 2018 update". Nucleic Acids Research. 46 (D1): D762–D769. doi:10.1093/nar/gkx1020. PMC 5753355. PMID 29106570.

- ↑ Frankish A, Diekhans M, Jungreis I, Lagarde J, Loveland JE, Mudge JM, et al. (December 2020). "GENCODE 2021". Nucleic Acids Research. 49 (D1): D916–D923. doi:10.1093/nar/gkaa1087. PMC 7778937. PMID 33270111. S2CID 227260109.

- ↑ "GENCODE Project Participants". Genome BioInformatics Research Lab. c. 2005. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- 1 2 "GENCODE – Statistics". GENCODE. Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute. c. 2014. Archived from the original on 20 December 2020. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- ↑ "GENCODE – Goals". GENCODE. Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute. c. 2013. Retrieved 5 September 2014.

- 1 2 Searle S, Frankish A, Bignell A, Aken B, Derrien T, Diekhans M, et al. (2010). "The GENCODE human gene set". Genome Biology. 11 (Suppl 1): 36. doi:10.1186/gb-2010-11-S1-P36. PMC 3026266.

- ↑ "Ensembl - Homepage". Ensembl. August 2014. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- ↑ Kokocinski F, Harrow J, Hubbard T (October 2010). "AnnoTrack--a tracking system for genome annotation". BMC Genomics. 11: 538. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-11-538. PMC 3091687. PMID 20923551.

- ↑ "Biodalliance - Homepage". 20 December 2020.

- ↑ Gerstein MB, Bruce C, Rozowsky JS, Zheng D, Du J, Korbel JO, et al. (June 2007). "What is a gene, post-ENCODE? History and updated definition". Genome Research. 17 (6): 669–81. doi:10.1101/gr.6339607. PMID 17567988.

- ↑ "Human Genome Project - Homepage". 20 December 2020.

- ↑ "ENCODE data in Ensembl". Ensembl. August 2014. Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- 1 2 Steijger T, Abril JF, Engström PG, Kokocinski F, Hubbard TJ, Guigó R, et al. (December 2013). "Assessment of transcript reconstruction methods for RNA-seq". Nature Methods. 10 (12): 1177–84. doi:10.1038/nmeth.2714. PMC 3851240. PMID 24185837.