| Editor-in-chief | Rafael Lindqvist |

|---|---|

| Categories | Satirical magazine |

| Founded | 1898 |

| Final issue | 1922 |

| Country | Finland |

| Based in | Helsinki |

| Language | Swedish |

Fyren (Swedish: The Lighthouse) was a satirical magazine focusing on politics which was published in Helsinki, Finland, between 1898 and 1922. It described itself as a social satire publication which supported free visual and written expressions.[1]

History and profile

Fyren was started in Helsinki in 1898.[2] Rafael Lindqvist was the editor-in-chief of the magazine which targeted educated classes.[1] The magazine declared that it was not interested in party politics.[3] However, it adopted an anti-Semitic and anti-Bolshevik political stance[2][4] and supported Swedish nationalism and conservatism.[3]

Major contributors of Fyren included the cartoonists Alex Federley, Emil Cedercreutz, Signe Hammarsten-Jansson and Antti Favén.[2] It was subject to strict censorship by the Russian authorities until the independence of Finland in 1917.[1] In addition, a cartoonist of the magazine, Eric Vasström, was imprisoned for three months due to a caricature depicting a Russian noblewoman dancing with a Finnish commoner.[1][5] The caricature was published after the visit of the Russian royal family to Finland and was regarded as an insult to the Russian royals.[5]

Fyren published a special issue in 1915 to celebrate the 50th birthday of Jean Sibelius which covered cartoons featuring Sibelius.[6]

Tuulispää, another satirical magazine, was the rival of Fyren in regard to the conflict about the use of the Finnish and Swedish languages. The former supported the Finnish language, whereas Fyren was a supporter of the use of the Swedish language.[1] However, the same writers contributed to both titles.[1]

Fyren and Tuulispää sold only 3,000–4,000, but another satirical magazine of the period, Kurikka, managed to sell 20,000 copies.[3]

Fyren ceased publication in 1922 and was replaced by another satirical magazine entitled Blinkfyren which was also edited by Rafael Lindqvist.[4][7]

Gallery

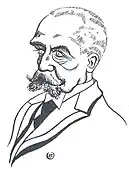

Caricature of Carl Alexander Armfelt by Uno Zeipel dated 1905

Caricature of Carl Alexander Armfelt by Uno Zeipel dated 1905 A cartoon from Fyren dated 1917 alludes to the Swedish People's Party's poster "The man with the flag"

A cartoon from Fyren dated 1917 alludes to the Swedish People's Party's poster "The man with the flag" A cartoon by Alex Federley dated 1906

A cartoon by Alex Federley dated 1906 A cartoon from Fyren dated 1906 featuring expelled politicians of the Social Democratic Party of Finland

A cartoon from Fyren dated 1906 featuring expelled politicians of the Social Democratic Party of Finland

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ainur Elmgren (2020). "Visual Stereotypes of Tatars in the Finnish Press from the 1880s to the 1910s". Studia Orientalia Electronica. 8 (2): 26–27. doi:10.23993/store.82942.

- 1 2 3 "Fyren". Uppslagsverket Finland (in Swedish).

- 1 2 3 Anni Kangas (2007). The Knight, the Beast and the Treasure: a semeiotic inquiry into the Finnish political imaginary on Russia, 1918-1930s (PhD thesis). University of Tampere. p. 61,63. hdl:10024/67797.

- 1 2 Fred Andersson (6 April 2014). "Visuell propaganda i Finland 1900-1945". abo.fi (in Swedish). Retrieved 7 October 2023.

- 1 2 Marja Seliger (2014). Visual Rhetoric in Design Activism. São Paulo: Editora Edgard Blücher. p. 602. doi:10.5151/despro-icdhs2014-0087.

- ↑ Riitta Ojanperä (2014). "From a Young Genius to a Monument". In Hanna-Leena Paloposki (ed.). Sibelius and the World of Art. Vol. 70. Helsinki: Ateneum Publications. p. 14. ISBN 978-952-7067-11-6.

- ↑ Peter Mickwitz (1 September 2022). "Peter Mickwitz: Blinkfyren och den finlandssvenska fascismen". Förlaget (in Swedish). Retrieved 7 October 2023.

External links

Media related to Fyren at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Fyren at Wikimedia Commons