Frank H. T. Rhodes | |

|---|---|

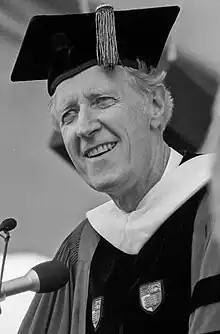

Rhodes in 1987 | |

| President of Cornell University | |

| In office 1977–1995 | |

| Preceded by | Dale R. Corson |

| Succeeded by | Hunter R. Rawlings III |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Frank Harold Trevor Rhodes October 29, 1926 Warwickshire, England |

| Died | February 3, 2020 (aged 93) Bonita Springs, Florida, U.S. |

| Alma mater | University of Birmingham |

Frank Harold Trevor Rhodes (October 29, 1926 – February 3, 2020) was the ninth president of Cornell University from 1977 to 1995.[1]

Biography

Rhodes was born in Warwickshire, England, on October 29, 1926, the son of Gladys (Ford) and Harold Cecil Rhodes.[2][3] He was educated at Solihull School from 1937–45, during which time he was elected as head boy. Rhodes then attended the University of Birmingham, graduating with a Bachelor of Science degree in 1948, and then went on to complete a Ph.D. there, in geology, in 1950; later, in 1963, he also earned a third degree from Birmingham, a D.Sc. (Doctor of Science), also in geology.[3][4] Following his doctoral studies, he spent a year at the University of Illinois as a Fulbright scholar (1950–51).[3]

Rhodes taught geology at the University of Durham between 1951 and 1954. In 1954 he returned to the University of Illinois as an assistant professor and was named an associate professor in 1955. In 1956 he moved to the University of Wales, Swansea as head of the department of geology and in 1967 he was named dean of faculty of science. During this time Rhodes lectured at other institutions such as Cornell in 1960. In 1965 and 1966 he served as a visiting research fellow at Ohio State University.

Rhodes joined the University of Michigan faculty as professor of geology and mineralogy in 1968. In 1971, he was named dean of the College of Literature, Science and the Arts. Prior to assuming the presidency at Cornell he served for three years as vice president of academic affairs at Michigan. Rhodes was elected the ninth President of Cornell University on February 16, 1977, and he assumed the office on August 1, 1977. He served until June 30, 1995. At the time of his retirement, he was the longest-serving president in the Ivy League. He was a professor emeritus of geology at Cornell.

In addition to his positions in academia, Rhodes played a part in government. He was appointed as a member of the National Science Board under President Ronald Reagan, and as a member of the President's Educational Policy Advisory Committee by President George H. W. Bush. Between 1984 and 2002 Rhodes served on the Board of Directors of General Electric. Rhodes died in Bonita Springs, Florida, on February 3, 2020, at age 93.[4]

Rhodes was a member of both the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the American Philosophical Society.[5][6]

Cornell presidency

During his eighteen-year tenure as president, the percentage of minority students grew from 8 percent in 1977 to 28 percent in 1994. The number of women and minority members of the faculty more than doubled. In the final years of his presidency a capital campaign raised $1.5 billion. In 1995 the building that houses what was then known as the Cornell Theory Center was named Frank H. T. Rhodes Hall. Cornell also has a professorship honoring Rhodes; Frank H.T. Rhodes Class of '56 University Professors are appointed to three-year terms. In 2010, the university also created new postgraduate student fellowships named after Rhodes to support students committed to the field of public interest law, and enable them to gain in-depth experience in work on behalf of the poor, the elderly, the homeless, and those deprived of civil rights.[7]

Opposition to divestment

Rhodes, a descendant of Cecil Rhodes, defied the international call for divestment of university endowments and other investment portfolios from South Africa-related stocks during the massive anti-apartheid divestment campaign of 1985-1987, with Cornell arresting hundreds of peaceful student and faculty protestors calling for divestment even as many other leading US universities divested from South Africa-related holdings.[8][9][10][11][12]

Campus expansion

Frank Rhodes presided over the construction of more buildings during his tenure than any previous president of Cornell.[13] In addition to many scientific buildings including Snee Hall, Corson-Mudd, Rhodes oversaw construction of the Kroch Library, the Schwartz Performing Arts Center, a new Statler Hotel, and Akwe:kon, the first residential program house founded to celebrate North American Indigenous cultures.[14][13]

The three original buildings of the New York State College of Agriculture, Stone Hall, Roberts Hall, and East Roberts Hall, had been considered obsolete and hazardous since 1973, when a study conducted by State University of New York suggested that renovation would cost over $14 million.[15] Provost Kennedy and dean of agriculture David Call secured funding from New York State to replace them with two new buildings, which eventually became Kennedy-Roberts Hall.[13] The old buildings were demolished despite opposition by the City of Ithaca and local preservationists, after several years of court battles.[13][16][17] [18]

Another controversial Rhodes construction project was a proposed eight-story, 252,000-square foot building to be cited on the edge of Cascadilla Gorge.[13] A number of faculty, residents, and local officials opposed the plan as being insensitive to the visual and ecological effects on the gorge.[13] The proposed building's height was eventually reduced and the site moved thirty feet further from the gorge than initially proposed.[13] The Engineering and Theory Center opened in 1990, and in 1995 the building was renamed Frank H.T. Rhodes Hall.[13]

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Frank H. T. Rhodes". Cornell University. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- ↑ Who's Who in the World: 1991-1992. Wilmette, Ill.: Marquis Who's Who, 1990.

- 1 2 3 "Frank H.T. Rhodes." Gale Literature: Contemporary Authors. Farmington Hills: Gale, 2018. Retrieved via Gale in Context: Biography database, February 28, 2020.

- 1 2 Lamb, Anna (4 February 2020). "Frank Rhodes, Cornell's ninth president, dies at 93". Ithaca Voice. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ↑ "Frank Harold Trevor Rhodes". American Academy of Arts & Sciences. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

- ↑ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

- ↑ "Frank HT Rhodes Public Interest Fellowship". Cornell Law School. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- ↑ "African Activist Archive". africanactivist.msu.edu. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- ↑ "Guide to the Cornell divestment movement collection, 1983-1987". rmc.library.cornell.edu. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- ↑ Saha, Ambarneil; Masroor, Emad; Chowdhury, Hadiyah (17 March 2016). "GUEST ROOM | On Divestment and Hypocrisy". The Cornell Daily Sun. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- ↑ "Shorting the Devil". Cornell Business Review. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- ↑ Altschuler, Glenn C.; Kramnick, Isaac (12 August 2014). Cornell: A History, 1940–2015. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-7188-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Altschuler, Glenn C.; Kramnick, Isaac (2014). Cornell: a history, 1940 - 2015. Ithaca NY: Cornell University Press. pp. 254–255. ISBN 9780801444258. Retrieved 27 August 2023.

- ↑ "Akwe:kon". American Indian and Indigenous Studies Program. Retrieved 27 August 2023.

Akwe:kon: The first residential program house in the nation founded to celebrate North American Indigenous cultures.

- ↑ Gesensway, Deborah (4 September 1985). "State report recommends wrecking ball for Stone Hall". The Ithaca Journal. pp. 1, 11. Retrieved 27 August 2023.

- ↑ Genensway, Deborah (5 February 1986). "Battle over Ag Quad buildings continues in court". Ithaca, New York: The Ithaca Journal. Retrieved 27 August 2023.

- ↑ Sharpe, Rochelle (22 February 1986). "Decision on Stone Hall could come Monday from Albany". Ithaca, New York: The Ithaca Journal. Gannett News Service. pp. 1, 8. Retrieved 27 August 2023.

- ↑ Gesensway, Deborah (25 March 1986). "State judge rules Cornell needed permit to demolish Stone Hall". Ithaca, New York: The Ithaca Journal. Retrieved 27 August 2023.

External links

- Cornell Presidency: Frank H.T. Rhodes

- Cornell University Library Presidents Exhibition: Frank Howard Trevor Rhodes (Presidency; Inauguration)