Flat-chested kitten syndrome (FCKS) is a disorder in cats wherein kittens develop a compression of the thorax (chest/ribcage) caused by lung collapse. This is a soft-tissue problem and is not caused by vertebral or bony malformation. However, lung collapse can be a secondary symptom caused by bony deformity affecting the thorax such as pectus excavatum. In mild cases, the underside of the chest becomes flattened (hence the name of the condition); in extreme cases the entire thorax is flattened, looking as if the kitten has been stepped on. The kitten will appear to go from normal to flat in the space of about 2–3 hours, and will usually then stabilise. FCKS is frequently misdiagnosed as pectus excavatum due to inadequate veterinary literature or lack of experience with the condition on the part of the clinician.

FCKS is most frequently caused by collapsed lungs (and not as formerly believed, by a muscle spasm in the intercostal muscles). There are numerous causes for lung collapse, and therefore numerous causes for FCKS. One possible cause for flat chestedness that develops soon after birth is atelectasis.

Causes of atelectasis include insufficient attempts at respiration by the newborn, bronchial obstruction, or absence of surfactant (a substance secreted by alveoli that coats the lungs and prevents the surfaces from sticking together). Lack of surfactant reduces the surface area available for effective gas exchange causing lung collapse if severe. There can be many reasons for atelectasis in kittens, but probably the most common cause is prematurity. Newborn atelectasis would not be unusual in a very large litter of kittens (such as 10), where the size of the litter may lead all the kittens to be small and mildly underdeveloped.

Unlike human babies, kittens are born very immature: blind, deaf, the intestinal tract not fully developed etc., so even slight prematurity may tip them over the edge from being viable to non viable. Many FCKS kittens may have fallen just the wrong side of this boundary in their development at the time of birth. Further, if a kitten does not scream or open its lungs well enough at birth, even if it is fully mature and has sufficient surfactant, it may end up with atelectasis. Patches of atelectasis in the lungs mean that part of a lung is not operating properly. If the kitten goes to sleep and its respiratory rate drops, the patches of atelectasis can slowly expand until large areas of the lung collapse and cannot be reinflated. Good advice to any breeder therefore would be to ensure that kittens cry loudly when they are born, to make sure that the airways are clear, but also that the lungs expand as fully as possible. (This was the reason newborn babies were always held upside down immediately after birth (so that any residual fluid drains downwards) and smacked to make them cry strongly.)

Some kittens suffer from congenital 'secondary' atelectasis, which presents shortly after birth. There have been no reports of kittens born flat (primary atelectasis). Hyaline membrane disease is a type of respiratory distress syndrome of the newborn in which there is formation of a hyaline-like membrane lining the terminal respiratory passages, and this may also be a (rarer) cause of FCKS. Pressure from outside the lung from fluid or air can cause atelectasis as well as obstruction of lung air passages by mucus resulting from various infections and lung diseases – which may explain the development of FCKS in older kittens (e.g. 10 days old) who are not strong enough to breathe through even a light mucus, or who may have inhaled milk during suckling.

Tumors and inhaled objects (possible if bedding contains loose fluff) can also cause obstruction or irritation of the airway, leading to lung collapse and secondary atelectasis. In an older cat the intercostal muscles are so well developed, and the ribs rigid enough that the ribcage will not flatten if the lung collapses: in kittens the bones are much more flexible, and the tendons and muscles more flaccid, allowing movement of the thorax into abnormal positions.

Other causes of lung collapse can include diaphragmatic hernia, or diaphragmatic spasm (breeders report the position of the gut and thorax as appearing to be like a 'stalled hiccup'). Diaphragmatic spasm is easily checked by pinching the phrenic nerve in the neck between the fingertips. Kittens with this type of FCKS will improve almost immediately, but may require repeated pinching to prevent the spasm from recurring.

Evidential basis and statistical analysis

Almost all reporting of FCKS is treated as anecdotal, since it comes from breeders and not from veterinary practitioners. However, in the absence of robust clinical studies breeder-reporting is the only source of information currently available. Reporting about type of FCKS is hampered by the lack of differentiation between one type and another by both breeders and vets. The data informing this article came from three sources:

- Analysis of emails reporting cases of FCKS sent to the owner of a website giving information about the condition and methods of treatment, 1999-2019 [87 of these kittens were examined in person by the author]

- Data gathered by the THINK project 2005-2015 who published an online questionnaire (the project is now defunct)

- Directly solicited reports requested from 27 individual breeders of Abyssinian (4 responded) and 35 breeders of British Shorthair (2 responded) in the UK

The 20-year analysis was compared with the Governing Council of the Cat Fancy in the UK (GCCF) analysis of numbers of kittens registered during the same period. The full report is to be published during 2020.[1]

Only direct reports from owners (362) about their own cats or vets examining kittens (2) were considered. Kittens exhibiting any other condition (including pectus excavatum) were excluded. The overwhelming majority of reports (76%) were of single FCKS cases in a litter, with the remainder whole or part litters. The data comprised 311 reports of litters of kittens in which one or more developed FCKS, for a total of 464 affected kittens (see table).

Reports in which the sex was specified showed breakdown by sex of male 56%/female 44%. 16 breeders reported that whereas they might have expected the smallest kitten in a litter (if any) to develop FCKS, it was the largest and strongest kittens that developed flat chests, and these were often males. The condition does not appear to be sex-linked, but the preponderance of male kittens in this reporting group may be due to the fact that males tend to be larger than females and these are the kittens getting most milk or suckling hardest because they are stronger, in which case the type of FCKS in these litters may have been due to colic caused by overfeeding (see Causes, below).

Reports originated from 21 countries (Australia (15), Austria (11), Belgium (2), Canada (8), Denmark (3), Finland (2), France (24), Germany (13), Hungary (1), Japan (2), Netherlands (14), New Zealand (6), Norway (5), Portugal (1), Singapore (1), Slovakia (1), South Africa (5), Sweden (11), Switzerland (1), UK (100), USA (85)) and covered 39 breeds (including non-pedigree domestic shorthair, non-pedigree domestic longhair, and some ‘unrecognised’ crosses between two pedigree breeds or pedigree breeds x DSH). 10 reports did not specify breed.

High numbers of reports in certain breeds has in the past been taken to imply that some breeds are more prone to the condition than others, but the data is skewed by various factors: a) the numbers of kittens bred; b) cluster-reporting in response to articles in breed club circulars or c) the work of a particular group of breeders (cf Burmese) in attempting to address a problem that they had seen in their own lines d) the culture within an individual breed of information-sharing or reporting problems. Breeders are generally not inclined to discuss health issues because of a culture of blame and gossip, having a dramatic effect on information-sharing. No ‘cluster’ triggers have been identified for the relatively high number of reports in the Maine Coon or Bengal breeds, while the Burmese cat club commissioned a study into the condition in 1997 by Sturgess et al, and the THINK project solicited reports from Burmese breeders specifically. However statistics on the registration of kittens provided by the GCCF show that Bengal, Burmese and Maine Coon are consistently in the top nine breeds by number of kittens registered (see table). The breeds showing highest numbers of kittens registered therefore broadly correlate demographically to reports of FCKS. More significant is perhaps the low number of reported cases in the British Shorthair (especially when compared with the Manx), but this seems to be attributable to the culture of breeders and level of diagnostic awareness in that group.

Mortality: of 195 cases where the outcome was notified, 88 died, or were euthanised due to distress; 107 recovered and survived beyond 3 months of age. Those that recovered fully did not appear to suffer any long-term respiratory effects (Interference of the development of the upper spine while the body was held in an incorrect position by the FCKS led to long-term kyphosis in some, but not all, cases), although reporting is patchy.

Mentions of FCKS in the veterinary literature (usually no more than a single sentence) include no descriptive information and have no evidential basis, in particular the claim in Saperstein, Harris & Leipold (1976) that the condition may be hereditary, which has been repeated in subsequent literature.

Onset and diagnosis

FCKS develops usually in kittens around three days of age, and sometimes affects whole litters, sometimes only individuals or part of a litter. Kittens can go flat any time during early maturation, some flattening as late as 10 days of age or (in very rare cases) later. It is possible that the later-developing cases are due to Respiratory tract infection or pneumonia. Until 2010 FCKS was believed to be caused by a spasm in the intercostal muscles, but re-examination of old post-mortem data (i.e. that kittens remain flat even when they are dead and therefore cannot maintain a muscular spasm) and new data has led to the conclusion that flattening is caused by failure of the lungs to inflate normally or, when it occurs in older kittens, by lung collapse. This cause is now cited by the veterinary community (Sturgess 2016) but without any source acknowledgement.

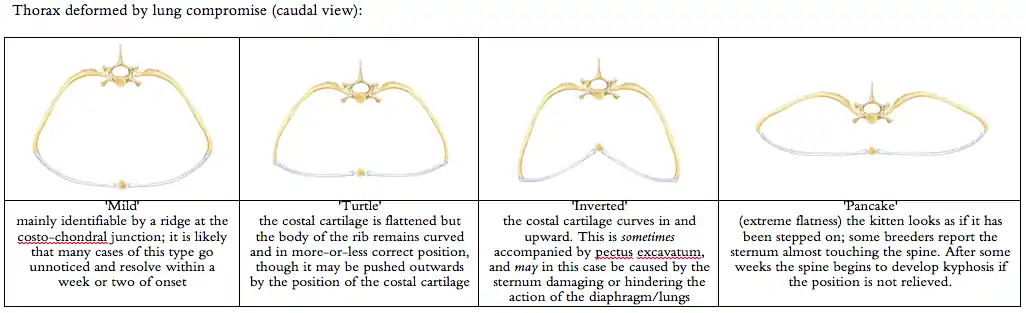

Gross physical symptoms include flattening of the underside of the thorax in moderate cases (a ridge can usually be felt along the sides of the ribcage, running parallel to the spine); complete flattening of the upper body in extreme cases (the kitten looks as if it has been stepped on); moderate to extreme effort and/or gasping during breathing; the gut is drawn upwards during the in-breath. Breathing is not usually rapid (as in pneumonia or pyrexia) but at a normal rate when compared with unaffected kittens. The position of the thorax and activity of the abdomen is not unlike that seen during normal hiccups, but the sudden spasm in hiccups is slowed down or halted in FCKS: where a hiccup releases, returning the body to a normal position, FCKS breathing does not release. There may be involvement with digestive difficulty in FCKS kittens (see Colic, below).

Determining whether a kitten has FCKS or not can be difficult with only text descriptions: a mild case of FCKS causes the thorax to feel similar to the shape of a banana when held curve downward. The ribcage is not fixed in position, and the most noticeable effect in mild cases is the ridge along the side of the ribcage.

The condition causes weight-gain to halt, respiratory distress, inability to feed normally and, in a significant proportion of cases, death. However, since a significant percentage of kittens survive the condition immediate euthanasia is not indicated, and supportive treatments can be employed to increase the likelihood of survival (see Treatment, below).

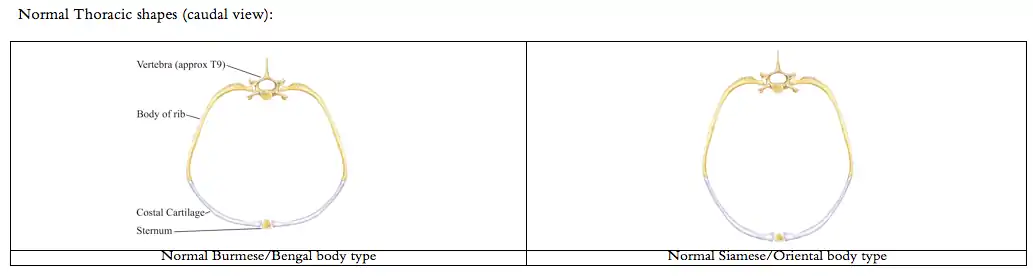

The condition is often misdiagnosed as Pectus excavatum,[2] with which it has no direct connection, although FCKS kittens may also have PE. Although the condition is believed to be more prevalent in the Burmese breed it is found in every breed of cat, including non-pedigree domestic cats, and the apparent prevalence in the Burmese is most likely due to better communication between breeders and reporting of the condition, as well as the naturally more barrel-shaped chest of this particular genotype.[3] Since early reporting of the condition identified the Burmese as susceptible the Bengal breed, with a similar physiology, has emerged, and shows a similarly large number of FCKS kittens, however this may be due to specific interest in the condition among those working with the breeds. It is reported in all breeds and in domestic non-pedigree cats, both those kept as pets and those living as 'barn cats'. An article in a Swedish cat club newsletter about FCKS led to a spike in reporting of the condition in Ragdolls in Sweden.

Egyptian Mau kitten with FCKS |

Rex kitten with FCKS and Kyphosis - note narrowing of thorax around the shoulders |

Oriental kitten with moderate to extreme FCKS. Pectus Excavatum is not present. The kitten was wrapped in a 'corset' for about 2 weeks. It is now a healthy adult. |

The syndrome is life-threatening in a significant number of cases (possibly around 40%) mainly due to a lack of understanding of the underlying cause of the condition, failure to treat colic (leading to slow starvation) and insufficient sources of information in veterinary literature.

Causes

Genetic/heredity

There is no statistical evidence to suggest that FCKS may be due to genetic factors: certain bloodlines seem to produce a preponderance of kittens with the condition, but this may be due to enhanced reporting within the breed. The literature citing heredity as a cause (Saperstein, Harris & Leipold, 1976) does not provide any evidential support and the information is repeated in later literature citing that source as authority. The majority of cases are of single kittens, with low but significant numbers of whole or part litters reported. Numerous breeders experience periods in which FCKS seems to occur over a number of matings, but then stops, suggesting an environmental cause. Incidences of the condition have been reported in many litters that were repeat matings of previously healthy litters; matings repeated after the incidence of FCKS do not produce flat kittens any more frequently than non-repeat matings; recovered FCKS that have been bred from have likewise not produced offspring that suffered from the condition any more frequently than normal cats, but numbers in this category are obviously low. It is possible that some lines in which the queens provide excessive milk may lead to colic-related FCKS in the kittens, leading to the supposition of heredity. Although after experiencing cases of FCKS most breeders do not repeat matings. In 59 cases of repeat matings 52 litters did not result in FCKS again while 7 did.

Developmental

It is possible that the lung collapse in neo-nates (i.e. around 3 days of age) could be due to a lack of surfactant – the coating of the inside of the lung that prevents the inner surfaces of the alveoli from sticking together. (Causes of surfactant deficiency are not discussed here, but the role of surfactant is discussed in a number of articles in the British Journal of Anaesthesia vol. 65, 1990.[4]). Kittens are born immature in many ways, and full inflation of the lungs does not happen immediately, but takes place gradually over a period of several days after birth. Although a kitten may seem active and thriving, its lungs will not be fully inflated until approximately day 3 after birth. Thus if inflation fails to happen correctly the negative pressure in the chest cavity will cause the ribcage – which is extremely flexible – to collapse inward, dragged in by the lungs, and not collapsing due to muscular cramping, and compressing the lungs.

Infection

Neo-natal and later lung collapse may be due to lung infection, or possibly to a malfunction in the epiglottis, causing the in-breath to draw air into the digestive tract rather than the lungs. A short term malfunction of this sort may be perpetuated by the resulting colic creating a feedback loop that interrupts the correct breathing process.

Autopsy and analysis of lung aspirate in a group of flat-chested kittens bred by a US Vet showed the presence of Herpes virus.

Diaphragmatic spasm

Spasm in the diaphragm leads to the muscle 'locking up' so that all breathing effort falls to the intercostal muscles. The resulting loss of movement causes the lungs to deflate gradually. This is easily diagnosed and treated (see Treatment below) by short-term interruption of the phrenic nerve.

Colic

A kitten that has difficulty in breathing is very likely also to suffer from colic (which can cause weight loss in the early development of a normal kitten), and a very small daily (or twice daily) dose of liquid paraffin (one or two drops placed on the tongue of the kitten, or 0.1 ml) should help to alleviate this problem. FCKS kittens who do not maintain weight are usually among the group which die, but many of them may simply be unable to feed properly due to colic, becoming increasingly weak and lethargic, and fading due to malnutrition as much as to the thoracic problems.

Colic has many causes, but in a kitten with respiratory difficulty it is possible that a malfunction during the breathing process leads the kitten to swallow air instead of taking it into its lungs. The GI tract fills with air while the lungs do not receive a proper air supply, preventing them from inflating fully. Pressure from the stomach exacerbates the condition. Treating for colic with liquid paraffin seems to shorten recovery time from 4–10 weeks to a matter of days.

Treatment

Treatment is difficult to define given the number of different causes and the wealth of anecdotal information collected by and from cat breeders. Treatments have hitherto been based on the assumption that FCKS is caused by a muscular spasm, and their effectiveness is impossible to assess because some kittens will recover spontaneously without intervention. FCKS cannot be corrected surgically.

Diaphragmatic spasm is easily tested for and treated by short term interruption of the phrenic nerve. The nerve runs down the outside of the neck where the neck joins to the shoulder, within a bundle of muscles and tendons at this junction. The cluster can be pinched gently and held for a few seconds each time. Kittens with spasmodic FCKS will show almost immediate improvement, but the treatment may need to be repeated several times over a few days as the spasm may have a tendency to recur, particularly after suckling. It is sometimes evident that the spasm only affects one side of the diaphragm, as interruption of the nerve is only necessary or effective on one side.

Continuous positive air pressure (CPAP) is used in human babies with lung collapse, but this is impossible with kittens. It is possible that the success of some breeders in curing kittens by splinting the body, thus putting pressure on the ribcage, was successful as it has created the effect of positive air pressure, thus gradually re-inflating the lungs by pulling them open rather than pushing them open as is the case with CPAP (see below).

Drugs

The use of steroids (dexamethasone) coupled with an antibiotic (amoxicillin) will support the kitten in a number of ways, the steroid enhancing maturation and the antibiotic addressing the possibility of underlying infection and compensating for the immuno-depressant properties of the steroid. The steroid will also encourage the kitten to feed more energetically, keeping its weight up. However, the primary supportive mechanism must be nutritional. Kittens who are only supported with feeding and do not receive drugs seem to have a similar prognosis to those receiving drugs. Drug treatment cannot be used to replace nutritional support (i.e. supplementary feeding). Two breeders having read the report by Sturgess et al (which was inconclusive) believe that taurine plays a part in the condition. These breeders give the queen large doses of taurine (1000 mg) daily until the kittens recover – apparently within a few days. Long-term use of high doses of taurine should be monitored by a veterinarian.

Kittens have a much higher metabolism than adults, so drugs cannot simply be calibrated based on adult protocols but adjusted for weight. Antibiotics administered 2x daily in adults need to be given 3x daily in kittens, and doses given at 24-hour intervals in adults need to be given at 18- to 20-hour intervals in kittens. In addition, because the liver does not metabolise drugs as efficiently as in adults, a higher dose relative to body weight may need to be given. Little information is available in veterinary literature about drug dosing in neonates; almost all treatment protocols are based on adult animals. The neonatal human literature is here used as a guide. See Lawrence C. Ku and P. Brian Smith, 'Dosing in neonates: Special considerations in physiology and trial design' and multiple other sources of information. Observation of drug responses in neonatal kittens indicates increased frequency is essential.

Splinting and physical therapy

Splinting the kitten in a specially-constructed corset made from a rigid material such as a toilet roll, section of plastic bottle or high-density foam encourages the ribcage to a more normal position, and reported mortality seemed to decline when this practice was introduced.[5] This may be because encouraging the chest to a more correct position helps the lungs to re-inflate. However a large proportion of kittens cannot tolerate a splint, and the distress it causes is extremely counterproductive. It can also be dangerous in cases where pressure on the sides causes the sternum to move inwards rather than outwards, and should only be undertaken with veterinary support and advice. Some kittens recover without intervention, so it is not known whether the various treatments based on encouraging the thorax to return to a normal shape contributed to recovery.[6]

Some breeders have found that applying manual pressure to the sides of the ribcage can help, as the chest rounds out with encouragement (gentle pressure timed to coincide with the natural movement of the thorax in breathing), but usually the chest goes flat again as soon as massage is discontinued. It may however help in encouraging the lungs to inflate a little more with each breath, but should not be used if it causes distress to the kitten. Many breeders report that affected kittens seem to enjoy massage. Encouraging a kitten to lie on its side can be helpful, and draping another kitten (or the mother's arm) over it while it is sleeping on its side places a gentle continuous pressure on the ribcage which may also be helpful. If the kitten is uncomfortable it will move away. (It is important to ensure that pressure is not placed on the kitten if it is lying flat on its chest.)

Over-handling FCKS kittens can lead to unnecessary weight loss and lethargy, so the use of massage, waking the kitten for extra feeds from the mother etc. should be checked against gains and losses in weight. Some vets believe that encouraging the kitten to cry and also to have to move more to reach its mother may be helpful. There is no data from breeders supporting this theory.

Survival and long-term prognosis

It is difficult to determine whether a kitten that goes flat will survive or not. A good indicator is the weight of the kitten: those that continue to gain weight generally have a better chance of survival. Supplement feeding is therefore recommended in all cases, together with vitamin supplements,[5] although many of these kittens will not accept hand feeding. Liquid Paraffin to alleviate colic seems to be significant in assisting normal feeding and weight-gain.

Another indicator to the severity of the case is the use of the stomach when breathing: normal kittens use only the ribcage, a flat-chested kitten may manage to breathe only using the ribcage, or may suck the gut upwards with every breath – if the latter is the case then the likelihood of survival seems to be lower, though still not sufficient to warrant immediate euthanasia. If the condition is stable (i.e. the flatness does not increase over time) or improving, the kitten is more likely to survive. If the condition worsens over several days, survival is less likely.

Kittens with FCKS may die (or have to be euthanised) very soon after onset. There are two points at which breeders report kittens that were otherwise doing well deteriorating and dying: at 10 days of age and at 3 weeks. Generally, if the kitten is still flat, but survives the 3-week developmental stage, its prognosis is good. Many will have returned to a normal shape by this time. Those retaining some degree of flatness often grow out of the condition at any point in the ensuing 6 months, and the vast majority of survivors appear to lead normal lives with no side-effects, either physical or immunological.

FCKS kittens that survive but who have not been given any drug treatment or support other than supplementary feeding, generally recover over a period of 4–10 weeks, and are usually normal by 12 weeks of age, though some take as long as 6 months to normalise. In the very small number of kittens reported so far treated with steroids, antibiotics and liquid paraffin (to address colic) recovery is usually seen within a matter of days. Given the number of different types of FCKS these kittens (all with the minor form of the condition) may not be representative of all cases. More data is required for statistical analysis.

A small proportion of severe FCKS kittens are left with long-term respiratory problems, kyphosis, and in some cases cardiac issues caused by the compression of the thorax during the early developmental stages (particularly where the condition has been coupled with Pectus Excavatum). Cardiac issues are generally audible on physical examination; further indications include the kitten becoming breathless after play, less active than siblings, and failure to grow and develop normally.

Breeding with FCKS

Crucial in the decision to breed would be the primary cause of FCKS in the litter, which may or may not be genetic (see Heredity above). Some recovered FCKS adults have produced FCKS offspring in their turn, and some queens consistently produce flat kittens, so breeding from those lines is therefore inadvisable. However, repeat matings in which FCKS has appeared does not result in further FCKS kittens any more often than non-repeat matings. Queens and studs who consistently throw complete litters of kittens with the condition are generally neutered, but isolated instances of single flat kittens in an otherwise healthy litter seem to be unlikely to have a genetic component and neutering of parents of such kittens is not usually necessary in pedigree breeding, particularly where doing so may have detrimental effects on the gene pool.

If the cause of flattening is colic related to over-production of milk then this would not be cause for neutering. The only way to determine if the cause is digestive would be if the condition was alleviated by pinching the phrenic nerve and/or use of liquid paraffin to relieve colic, resulting in improvement in the condition.

Line-breeding or inbreeding is highly inadvisable in any situation, and particularly so in lines where FCKS has appeared, given the possibility of inheritance of any underlying condition or breeding factor that may cause kittens to develop FCKS.

Other conditions

Kittens with FCKS sometimes also show bony deformities such as pectus excavatum or kyphosis (characterised in kittens by a dip in the spine just behind the shoulder blades). Although a kitten may be born with these deformities, extreme forms of FCKS may cause kyphosis to develop in an otherwise normal kitten, as the kitten grows with the spine held in an abnormal position due to the flattened ribcage. When there are bony deformities in the upper body, or other problems present, these may contribute to malfunctioning in soft-tissue organs such as the respiratory and digestive systems.

Flat chestedness in other animals

Flat chest occurs in piglets and puppies, may be known in cattle (anecdotal information only), and is also recorded in humans, though in humans it may not be the same condition and is possibly a bone deformity.

References

- ↑ Reference will be provided when publication information is available.

- ↑ Kit Sturgess et al: An investigation of Taurine levels as a possible cause of FCKS. Burmese Cat Club Newsletter 1980, downloadable pdf files accessible from this page

- ↑ Edinburgh FAB resident, Royal Dick Veterinary Hospital: Report in FAB Journal (1993), vol. 31 (1) 71-72

- ↑ particularly B A Hills: The role of lung surfactant, British Journal of Anaesthesia 1990, 65, 13-29

- 1 2 "Treating Flat-chested kitten syndrome". Rameses Tonkinese.

- ↑ Although corsets can be improvised easily from e.g. plastic drinks bottles etc., one breeder has marketed a 'corset' design that she found successful with her kittens www.fck-flat-korsett.de

Bibliography

- Blunden, A. S., Hill, C. M., Brown, B. D. and Morley C. J. (1987) Lung surfactant composition in puppies dying of fading puppy complex. Research in Veterinary Science 42: 113–118

- Blunden, T. S. (1998) The neonate: congenital defects and fading puppies. In: Manual of Small Animal Reproduction and Neonatology. Simpson, G., England, G. C. W. & Harvey, M. (eds). British Small Animal Veterinary Association, Cheltenham, UK.

- Chandler, E. A., Gaskell, R. M., Gaskell, C. J. eds. (2004) Feline Medicine and Therapeutics. 3rd edn. Blackwell, Oxford (for BSAVA), 369. [Warning: this source mentions FCKS very briefly and refers to it as 'almost certainly hereditary'. No evidence, sources or further information are given.]

- Charlesworth, T. M., Schwarz, T., Sturgess, C. P. (2015) Pectus excavatum: computed tomography and medium-term surgical outcome in a prospective cohort of 10 kittens. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery Jun 18, 11

- Fossum, T. W., Boudrieau, R. J., Hobson, H. P., Rudy, R. L. (1989). Surgical correction of pectus excavatum using external splintage in two dogs and a cat. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 195: 91–97

- Hosgood, G., Hoskins J. D. (1998) Small Animal Paediatric Medicine and Surgery. Pergamon Veterinary Handbooks. Butterworth-Heinemann

- Malik, R. (2001) Genetic diseases of cats, Proceedings of ESFM Symposium at BSAVA Congress, Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery 3, 109–113

- Noakes, D. E., Parkinson, T. J., England, G. C. W. (2009) Arthur's Veterinary Reproduction and Obstetrics E-Book. 9th edn. Saunders/Elsevier, Edinburgh, 128. FCKS is listed in a table of hereditary defects in cats.

- Robinson (1991) Genetics for Cat Breeders 3rd Revised edition, Butterworth-Heinemann

- Saperstein G., Harris S., Leipold H.W. (1976). Congenital defects in domestic cats. Feline Practice, 6, 18.

- Schultheiss, P. C., Gardner, S. A., Owens, J. M., Wenger, D. A., Thrall, M. A. (2000). Mucopolysaccharidosis VII in a cat. Veterinary Pathology 37, 502–505.

- Soderstrom, M. J., Gilson, S. D., Gulbas, N. (1995) Fatal reexpansion Pulmonary Edema in a Kitten Following Surgical Correction of Pectus Excavatum. Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association 31, 133–136 doi:10.5326/15473317-31-2-133

- Sturgess C. P., Waters L., Gruffydd-Jones T. J., Nott H. M. R., Earle, K. E. (1997) Investigation of the association between whole blood and tissue taurine levels and the development of thoracic deformities in neonatal Burmese kittens. Veterinary Record 141, 566–570. [Warning: much information now superseded]

- Vella, C. M., Shelton L. M., McGonagle, J. J., Stanglein, T. W. (1999) Robinson's Genetics for Cat Breeders and Veterinarians, 4th edn, Butterworth-Heinemann

Literature on pectus excavatum

- Boudrieau, R. J., Fossum, T. W., Hartsfield, S. M., Hobson, H. P., Rudy, R. L. (1990). Pectus Excavatum in Dogs and Cats. Compendium of Continuing Education 12, 341–355

- Fossum, T. W, Boudrieau, R. J., Hobson, H. P. (1989). Pectus Excavatum in Eight Dogs and Six Cats. Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association 25, 595–605

- McAnulty, J. F., Harvey, C. E. (1989) Repair of pectus excavatum by percutaneous suturing and temporary external coaptation in a kitten. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 194, 1065–1067

- Shires, PK, Waldron, DR and Payne, J. (1988) Pectus Excavatum in Three Kittens. Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association 24, 203–208

External links

- Vetstream article on FCKS in journal Felis ISSN 2398-2950

- Flat-Chested Kitten Syndrome Archived 2013-02-08 at the Wayback Machine

- Marine Minnaert: Étude rétrospective de la cage thoracique plate chez le chat : caractéristiques épidémiologiques et cliniques, pronostic et aspects génétiques, PhD thesis (2014) pdf

- International Cat Care website; based on Sturgess 1997, which is out of date and incorrect in many particulars

- Sturgess C P, Waters L, Gruffydd-Jones T J et al (1997) Investigation of the association between whole blood and tissue taurine levels and the development of thoracic deformities in neonatal Burmese kittens. Vet Rec 141, 566-570

- Feline Medicine and Therapeutics By E. A. Chandler, R. M. Gaskell, C. J. Gaskell describes the condition very briefly and refers to it as 'almost certainly hereditary' without any evidence for doing so. No other information is given as to cause.

- In Arthur's Veterinary Reproduction and Obstetrics E-Book By David E. Noakes FCKS is listed in a table of hereditary defects in cats, again without any supporting citation or information

- Google Books link to article in Feline Medicine and Therapeutics By E. A. Chandler, R. M. Gaskell, C. J. Gaskell

- Sturgess, C. P. (2016) Thoracic wall deformities in kittens: what do you do? Australian and New Zealand College of Veterinary Scientists Science Week, Small Animal Medicine and Feline Chapters