.jpg.webp)

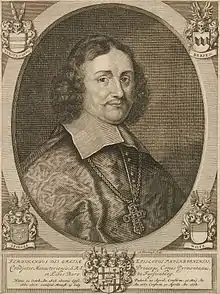

Ferdinand of Fürstenberg (German: Ferdinand Freiherr von Furstenberg), contemporaneously also known as Ferdinandus liber baro de Furstenberg, (26 October 1626 - 26 June 1683) was, as Ferdinand II, Prince Bishop of Paderborn from 1661 to 1683 and also Prince Bishop of Münster from 1678 to 1683, having been its coadjutor since 1667/68. He brought almost complete restoration to the Bishopric of Paderborn after the devastation of the Thirty Years' War.

In foreign policy, he generally followed the principle of armed neutrality, but tended to lean towards the French position. He distinguished himself as an author of historical works, a poet of Latin poetry and a correspondent with the great scholars of his time. He also emerged as a patron of the arts and religion and had numerous churches built or renovated. He is considered one of the most outstanding representatives of Baroque Catholicism.[1]

Background and education

Ferdinand of Fürstenberg was born on 26 October 1626 at Bilstein Castle in the Duchy of Westphalia into the Westphalian House of Fürstenberg. His father, Frederick of Furstenberg, was the Landesdrost or state governor for the Electorate of Cologne. His mother was Anna Maria (née von Kerpen). He was the eleventh child of their marriage. His siblings include clergyman, artist and officer, Caspar Dietrich of Furstenberg, the cathedral provost in Münster and Paderborn, John Adolphus of Fürstenberg, the diplomat and head of the family, Frederick of Furstenberg, the dean William of Furstenberg and the Landkomtur Francis William of Furstenberg. His godfather was Elector Ferdinand of Bavaria.

To the latter he owed the fact that he was given a diocesan stipend from Hildesheim at the age of seven . And thanks to the intercession of the emperor, in 1639 a benefice in the cathedral chapter of Paderborn was added to his income.

As was customary in the family, Ferdinand of Fürstenberg was given an exceptionally good education for a member of the nobility at that time.[2] Fürstenberg initially attended the Jesuit grammar school in Siegen. After that he studied philosophy in Paderborn and Münster.

After the death of his parents Fürstenberg returned for a time to Bilstein Castle, where the castellan introduced him to the basics of jurisprudence. In 1648 he began his studies into theology and law at the University of Cologne. There he came into contact with important scholars especially among the Jesuits.

He also came into contact with other leading scholars of his time, especially in Münster and Cologne. They included Aegidius Gelenius. In this period Fürstenberg began to carry out historical studies himself. In Münster he also came to know Fabio Chigi, the nuntius in the peace negotiations of the Thirty Years' War and, later, Pope Alexander VII.

In 1649 after completing his studies, he was given a place and vote in Paderborn's cathedral chapter. One year later he was installed as a subdeacon. He was invited to Rome by Fabio Chigi. There he met his brother, John Adolphus in 1652.[3]

Papal chamberlain and scholar in Rome

In Rome Fürstenberg worked as part of the retinue of Chigis. Through Chigis he came into contact with scholars there. He lived under the same roof with philologist Nikolaes Heinsius and they formed a lifelong friendship. He also had a close friendship with Lukas Holste. The latter motivated Ferdinand to undertake further language studies and arranged for him to have access to the Vatican library, which he ran. Fürstenberg also came into close contact with many Italian scholars.[4]

On the election of Fabio Chigi to the Papacy as Pope Alexander VII in 1655, Fürstenberg was appointed as Papal Private Chamberlain (Geheimkämmerer). Like his brother William later, Fürstenberg acted as an advisor to the Pope on German matters.

He was a member of an Academy of Fine Arts, later even becoming its president. In 1657 he was chamberlain to the archsodality at Campo Santo and Provisor of the German Kirche Anima.

But above all, he devoted himself to academic work, for example, producing numerous copies of documents from the Vatican archives. These included the Capitulatio de partibus Saxoniae by Charlemagne. Some finds he left to others to publish, some he published himself. In addition, he emerged as a sponsor of large-scale academic projects such as the publication of Acta Sanctorum by Jean Bolland and his successor, the Bollandists. The discovery of documents from his Westphalian homeland prompted Ferdinand's decision to write a history of the Bishopric of Paderborn.

In 1659 Ferdinand was ordained as a priest. As a result, he was given several benefices. These included the Priory of the Holy Cross in Hildesheim, a cathedral chapter position in Münster and the opportunity of another in Halberstadt.

In 1660 he became a papal legate and handed over the cardinalate to Francis William of Wartenberg. In addition he had to undertake diplomatic missions to Leopold I and many of the imperial princes. In Westphalia he also studied sources for his planned history of the bishopric. After his return to Rome Fürstenberg devoted himself mainly to historical research in the Vatican Archives.[5]

Time as a bishop

Ferdinand mainly had his brother, William, to thank for his election in 1661 as Bishop of Paderborn. His defeated opponent for the post was Maximilian Henry of Bavaria. Ferdinand was consecrated a bishop while still in Rome. He received his mitre in the German national church of Santa Maria dell’Anima from cardinal state secretary, Giulio Rospigliosi. He did not enter Paderborn 4 October 1661.

Internal politics in Paderborn

The state of Paderborn was still suffering from the consequences of the Thirty Years' War, because Ferdinand's predecessor had been unable to rebuild the economy for financial reasons. A primary objective for Ferdinand of Fürstenberg was thus the internal health of the land. His numerous construction projects were designed not least to employ the tradesmen of the prince bishopric. In addition, he encouraged the re-cultivation of fields that had lain waste. He had a forestry act passed and had censuses taken and tax lists made out. With limited success he support the establishment of factories. Even the healing baths in Bad Driburg had his support. To improve communications he supported a post coach service between Kassel and Amsterdam.

Following a treaty, the town of Lügde from the County of Pyrmont was annexed by the Prince Bishopric of Paderborn. During his time the conditions for access of the nobility to the state parliament were tightened. Henceforth the knights had to prove sixteen noble ancestors, if they wanted to have a seat and vote in parliament. He had the city of Paderborn strongly fortified.

The education system and Jesuit college set up under Dietrich of Fürstenberg were strongly promoted by Ferdinand. In addition, he has also tried to improve rural education and established new schools.

In a special way, Ferdinand is credited with enforcing the law of the land. If need be, strict sentences were passed on people, regardless of status. The marshal, Kurt von Spiegel, and a pastor from Buke were executed for example.[6]

Coadjutor and bishop in Münster

The election of the coadjutor in Münster was problematic, because von Galen had promised in his electoral capitulation not to create such a position. In particular, William of Furstenberg, who had meanwhile become the secret private chamberlain of the Pope, obtained a dispensatory papal bull in Rome that permitted Ferdinand to accede to the office. However, Ferdinand, along with his brothers John Adolphus of Furstenberg and Francis William of Furstenberg, guaranteed before the election that he would not intervene in the government of the Prince Bishopric of Münster until the death of von Galen. In the crucial vote, Ferdinand narrowly won at the expense of his rival, the Elector of Cologne, Maximilian Henry of Bavaria. Both sides appealed to the curia in Rome. But thanks not least to the influence of William of Furstenberg, Ferdinand's claim was confirmed. With that, the right of succession in Münster was decided. The local cathedral dean, Jobst Edmund von Brabeck, crossed over to the side of Cologne and became governor (Statthalter) of Hildesheim Abbey.[7]

The relationship with von Galen was problematic and their correspondence remained frosty. The military thinking of Galen was foreign to the scholarly nature of Ferdinand.[8]

In November 1679, following the death of von Galen, Ferdinand made a ceremonial entry into Münster. After decades of far-reaching military power politics the land hoped for peace and a reduction in military expenditure. So they viewed their new prince, who was regarded as peace-loving, with confidence.

In fact, after taking over the Prince Bishopric of Münster, Ferdinand pursued a new political line there. Von Galen had left large debts behind in the state of Münster. This, together with the more peaceful course adopted by Ferdinand, led to a sharp reduction in the number of Münster troops.

With regard to Sweden he renounced the conquests of von Galen's time. Only the Barony of Wildeshausen remained in the hands of the Bishopric of Münster as compensation for the damage inflicted by the Swedes. From France, Ferdinand received 50,000 Reichsthaler and Louis XIV promised to invest in the Catholic institutions in the Duchy of Bremen and Principality of Verden. Another externally oriented action for Münster was the destruction of Bevergern Castle as a gesture towards the Netherlands.

Internally, however, Ferdinand left few personal traces in Münster. His main effort remained the Prince Bishopric of Paderborn. The running of the state he left to the officials inherited from his predecessor.[9][10]

Church policy

Ferdinand took his priestly office very seriously. He himself said mass daily and performed the majority of pontifical masses himself. He undertook visitation trips through his area of responsibility and promoted the education of clerics in accordance with the principles of the Council of Trent. He based the appointment of priests on their performance. Because he saw the monasteries as centres for the renewal of the Catholic faith in people, he promoted these institutions. Pastoral activities paid particular attention to the Capuchin and Jesuit orders. He was supported by the Vicar General, Laurentius von Dript. Pope Innocent XI appointed Ferdinand in 1680 as Vicar Apostolic for Halberstadt, Bremen, Magdeburg, Schwerin and Magdeburg. The Catholic mission was to be entirely peaceful in these areas which had become Protestant.[11] He supported missionary work in Japan and China by the Jesuits through a large donation of 101,700 thalers.[12] Prince Bishop Ferdinand was closely linked to the Danish convert and natural historian, Niels Stensen, who he named in 1680 as his suffragan bishop in Münster. Stensen was not just significant for Ferdinand as a scholar, but also made a major contribution to the Missio Ferdinanda, to the mission foundation of 1682 for popular missions in Westphalia, to the Far East mission and to pastoral care in Northern Europe.[13]

Foreign policy

Overall Ferdinand pursued a peaceful foreign policy of armed neutrality, which avoided direct participation in war whenever possible. But Ferdinand's foreign policy swung between loyalty to the emperor and the leaning towards France. Ferdinand was greatly impressed by the personality of Louis XIV. Yet, following a family tradition, he initially remained a Habsburg adherent. Later on, his policy was oscillated before increasingly leaning towards the French side.

Despite his tendency to take a neutral stance, in 1665 he sent a small contingent of troops to support the war by the Bishop of Münster, Christoph Bernhard von Galen, who attacked the Netherlands together with Charles II of England. He opposed the war itself, but felt compelled to support von Galen, in order to be appointed by him as coadjutor of the Prince-Bishopric of Münster. Behind the scenes, Ferdinand tried to end the war, which ended with the Treaty of Cleves in 1666.[14]

Death

Ferdinand died on 26 June 1683 in Paderborn.

Works (selection)

- Monumenta Paderbornensia. 1669

- Cels[issi]mi ac rev[erendissi]mi principis Ferdinandi episcopi Paderbornensis … 1677 (UB Paderborn)

- Poemata Ferdinandi Episcopi Monasteriensis Et Paderbornensis, S. R. I. Principis, Comitis Pyrmontani, Liberi Baronis De Furstenberg. Paris, 1684 (UB Paderborn)

- Denkmale des Landes Paderborn. Translated from the Latin and furnished with a biographe of the author by Franz Joseph Micus. Paderborn: Junfermann, 1844 (UB Paderborn)

References

- ↑ On the topic of Baroque Catholicism, see Ernesti, Drei Bischöfe, pp. 50ff.

- ↑ Horst Conrad: "Splendor Familiae. Generationendisziplin und Politik bei der Familie von Fürstenberg. Eine Skizze." In: Südwestfalenarchiv 6th annual edition, 2006

- ↑ Lahrkamp, Ferdinand, pp. 119ff.

- ↑ Lahrkamp, Ferdinand, pp. 120ff.

- ↑ Lahrkamp, Ferdinand, pp. 122ff.

- ↑ Lahrkamp, Ferdinand, pp. 123–125.

- ↑ Lahrkamp, Ferdinand, pp. 127ff.

- ↑ On the relationship with von Galen, see Ernesti, Drei Bischöfe, pp. 54ff.

- ↑ Wilhelm Kohl: Das Bistum Münster. Part 7,1: Die Diözese (= Germania sacra. NF Vol. 37,1). De Gruyter, Berlin, 1999, ISBN 978-3-11-016470-1, pp. 276–278.

- ↑ Lahrkamp, Ferdinand, p. 134.

- ↑ For example, his church policy towards Pope Innocent XI, see Ernesti, Drei Bischöfe, p. 57.

- ↑ Lahrkamp, Ferdinand, p. 125

- ↑ Ernesti, Drei Bischöfe, pp. 58f.

- ↑ Lahrkamp, Ferdinand, pp. 125–127.

Literature

- Norbert Börste; Jörg Ernesti, eds. (2004), Ferdinand von Fürstenberg: Fürstbischof von Paderborn und Münster : Friedensfürst und guter Hirte (in German), vol. 42, Paderborn/Munich/Vienna/Zurich: Schöningh, ISBN 978-3-506-71319-3

- Hans J. Brandt, Karl Hengst: Die Bischöfe und Erzbischöfe von Paderborn. Paderborn, 1984, ISBN 3-87088-381-2, pp. 249–256.

- Jörg Ernesti (2004). "Fürstenberg, Ferdinand von". In Bautz, Traugott (ed.). Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL) (in German). Vol. 23. Nordhausen: Bautz. cols. 455–458. ISBN 3-88309-155-3.

- Jörg Ernesti: Ferdinand von Fürstenberg (1626–1683). Geistiges Profil eines barocken Fürstbischofs (= Studien und Quellen zur Westfälischen Geschichte. Vol. 51). Bonifatius, Paderborn, 2004, ISBN 3-89710-282-X.

- Jörg Ernesti: Drei Bischöfe – ein Reformwille. Ein neuer Blick auf Ferdinand von Fürstenberg (1626–83) und sein Verhältnis zu Christoph Bernhard von Galen und Niels Stensen. In: Westfalen, Hefte für Geschichte, Kunst und Volkskunde. Vol. 83, 2005, pp. 49–59.

- Helmut Lahrkamp: Ferdinand von Fürstenberg. In: Helmut Lahrkamp et al.: Fürstenbergsche Geschichte. Vol. 3: Die Geschichte des Geschlechts von Fürstenberg im 17. Jahrhundert. Aschendorff, Münster, 1971, pp. 119–149.

- Konrad Mertens: Die Bildnisse der Fürsten und Bischöfe von Paderborn von 1498 - 1891. Schöningh, Paderborn, 1892 (UB Paderborn)

- Franz Joseph Micus (1847), Lebensbeschreibung des Reichsfreiherrn Ferdinand von Fürstenberg, Fürstbischof's von Paderborn u. Münster (ULB Münster) (in German), Paderborn: Junfermann

- Josef Bernhard Nordhoff (1877), "Ferdinand von Fürstenberg", Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (in German), vol. 6, Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 702–709

- Klemens Honselmann (1961), "Ferdinand von Fürstenberg", Neue Deutsche Biographie (in German), vol. 5, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 93–94; (full text online)

External links

- Literature by and about Ferdinand von Fürstenberg in the German National Library catalogue

- Works by and about Ferdinand of Fürstenberg in the Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek (German Digital Library)

- Publications by or about Ferdinand of Fürstenberg at VD 17

- Ferdinand von Fürstenberg und seine Bücher – Dokumentation einer Ausstellung der Erzbischöflichen Akademischen Bibliothek Paderborn in der Volksbank Paderborn vom 8. bis 29. Dezember 1995. at the Wayback Machine (archived September 20, 2007)

- Digitale Sammlung der UB Paderborn: Büchernachlass Ferdinands von Fürstenberg

- Ausstellung Historisches Museum im Marstall Paderborn: Ein westfälischer Fürstbischof von europäischer Bedeutung Ferdinand II. von Fürstenberg 17. September 2004 bis 9. Januar 2005

- Eintrag auf catholic-hierarchy.org