The city of Vilnius, now the capital of Lithuania, and its surrounding region has been under various states. The Vilnius Region has been part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania from the Lithuanian state's founding in the late Middle Ages to its destruction in 1795, i.e. five centuries. From then, the region was occupied by the Russian Empire until 1915, when the German Empire invaded it. After 1918 and throughout the Lithuanian Wars of Independence, Vilnius was disputed between the Republic of Lithuania and the Second Polish Republic. After the city was seized by the Republic of Central Lithuania with Żeligowski's Mutiny, the city was part of Poland throughout the Interwar period. Regardless, Lithuania claimed Vilnius as its capital. During World War II, the city changed hands many times, and the German occupation resulting in the destruction of Jews in Lithuania. From 1945 to 1990, Vilnius was the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic's capital. From the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Vilnius has been part of Lithuania.

The population has been categorised by linguistic and sometimes also religious indicators. At the end of the 19th century the main languages spoken were Polish, Lithuanian, Belarusian, Yiddish and Russian. Both Catholic and Orthodox Christianity were represented, while a large proportion of the city's inhabitants were Jews. The "Lithuanian" element was seen as declining, while the "Slavic" element was increasing.

Census data are available from 1897 onward, although the territorial boundaries and ethnic categorisation have been inconsistent. The Jewish population decreased greatly because of the Holocaust of 1941–44, and subsequently, many Poles were removed from the city, but less so from the surrounding countryside. Consequently, recent Census figures show a predominance of Lithuanians in the city of Vilnius, but of Poles in the Vilnius district outside the city.

Ethnic and national background

Already in the 1st century, Lithuanian tribes inhabited Lithuania proper.[1] Slavicisation of Lithuanians in eastern and southeastern Lithuania began in the 16th century.[2] It is recorded that in 1554, Lithuanian, Polish and Church Slavonic were spoken in Vilnius.[3] The Statutes of Lithuania, officially enforced from 1588 until 1840, forbid Polish nobility to buy estates in Lithuania, hence a mass migration of Poles into the Vilnius region was impossible.[3] The Lithuanian nobility and Bourgeoisie was gradually Polonized over the 17th and 18th centuries.[3]

Until the end of the 19th century, Peasants in eastern Lithuania proper were Lithuanians.[3][4] This is attested by their un-Polonized surnames, and most Lithuanians in eastern Lithuania proper were Slavicized by schools and churches in the last quarter of the 19th century.[3][4]

Polonization resulted in the mixed language spoken in the Vilnius region by Tutejszy, where it was known as "mowa prosta".[5] It is not recognized as a dialect of Polish and borrows heavily from the Lithuanian, Belarusian and Polish languages.[5] According to Polish professor Jan Otrębski's article published in 1931, the Polish dialect in the Vilnius Region and in the northeastern areas in general are very interesting variant of Polishness as this dialect developed in a foreign territory which was mostly inhabited by the Lithuanians who were Belarusized (mostly) or Polonized, and to prove this Otrębski provided examples of Lithuanianisms in the Tutejszy language.[6][7] In 2015, Polish linguist Mirosław Jankowiak attested that many of the region's inhabitants who declare Polish nationality speak a Belarusian dialect which they call mowa prosta ('simple speech').[8]

After the partitions of Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

_Obwieszczenie_o_zakazie_rozmawiania_po_polsku%252C_Pud%C5%82o_663%252C_s_121.png.webp)

Most of the former lands of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania were annexed by the Russian Empire during the Partitions in the late 18th century.

While initially, these former lands had certain local autonomy, with local nobility holding the same offices as before the Partitions, after several unsuccessful rebellions in 1830–31 and 1863–64 against the Russian Empire, the Russian authorities engaged in intense Russification of the regions' inhabitants.

Following the failed November uprising all traces of former Polish–Lithuanian statehood (like the Third Statute of Lithuania and Congress Poland) were replaced with Russian counterparts, ranging from the currency and units of measurement to offices of local administration. The failed January Uprising of 1863–64 further aggravated the situation, as the Russian authorities decided to pursue the policies of forcibly imposed Russification. The discrimination of local inhabitants included restrictions and bans on usage of Lithuanian (see Lithuanian press ban), Polish, Belarusian and Ukrainian (see Valuyev circular) languages.[9][10][11][12] This however did not stop the Polonization effort undertaken by the Polish patriotic leadership of the Vilna educational district even within the Russian Empire.[13][14]

Despite that, the pre-19th-century cultural and ethnic pattern of the area was largely preserved. In the process of the pre-19th-century voluntary[15] Polonization, much of the Lithuanian nobility adopted Polish language and culture. This was also true to the representatives of the then-nascent bourgeoisie class and the Catholic and Uniate clergy. At the same time, the lower strata of the society (notably the peasants) formed a multi-ethnic and multi-cultural mixture of Lithuanians, Poles, Jews, Tatars and Ruthenians, as well as a small yet notable population of immigrants from all parts of Europe, from Italy to Scotland and from the Low Countries to Germany.

During the rule of the Russian tsars, Polish remained the Lingua franca as it had been in Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. By the middle of the 17th century, most Lithuanian upper nobility was Polonized. Over time, the nobility of the former Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth unified politically and started to consider themselves to be citizens of one common state. The leader of interwar Poland, the Lithuanian-born Józef Piłsudski, was an example of this phenomenon.[16]

Statistics

Following is a list of censuses that have been taken in the city of Vilnius and its region since 1897. The list is incomplete. Data are at times fragmentary.

Lebedkin's statistic of 1862

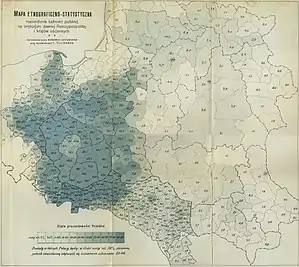

Michail Lebedkin used lists of the parish's inhabitants and judged their ethnicity based on their mother tongue.[3] Lebedkin considered Polish-speaking Catholics as Poles, yet the largest percentages of them were in districts of Dysna (43.4%), Vilnius (34.5%) and Vileyka (22.1%).[3] However, these districts were disconnected from ethnographic Poland and because there was no Polish colonisation, the sole conclusion is that the Polish-speaking Catholics were Polonized Lithuanians.[3]

Russian census of 1897

.jpg.webp)

.JPG.webp)

In 1897, the first Russian Empire Census was held. The territory covered by the tables included parts of today's Belarus, that is, the Hrodna, Vitebsk and Minsk voblasts. Its results are currently criticised concerning ethnic composition because ethnicity was defined by the language spoken. In many cases, the reported language of choice was defined by general background (education, occupation) rather than ethnicity. Some results are also thought of as skewed since Pidgin speakers were assigned to nationalities arbitrarily. Moreover, the Russian military garrisons were counted in as permanent inhabitants of the area. Some historians point out the fact that the Russification policies and persecution of ethnic minorities in Russia were added to the notion to subscribe Belarusians, Lithuanians, Ukrainians and Poles to the category of Russians.[18][19][20]

Russian Population Figures for the 1897 Census:

Area Language |

City of Vilna[21] | Vilensky Uyezd[22]

(no city) |

Troksky Uyezd[23] | Vilna Governorate[24] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belarusian | 6 514 | 4.2% | 87 382 | 41.85% | 32 015 | 15.86% | 891 903 | 56.1% |

| German | 2 170 | 1.4% | 674 | 0.32% | 457 | 0.22% | 3 873 | 0.2% |

| Lithuanian | 3 131 | 2.1% | 72 899 | 34.92% | 118 153 | 59.01% | 279 720 | 17.6% |

| Polish | 47 795 | 30.9% | 25 293 | 12.11% | 22 884 | 10.99% | 130 054 | 8.2% |

| Russian | 30 967 | 20.0% | 6 939 | 3.32% | 9 314 | 4.22% | 78 623 | 4.9% |

| Tatar | 722 | 0.5% | 49 | 0.02% | 799 | 0.19% | 1 969 | 0.1% |

| Ukrainian | 517 | 0.3% | 40 | 0.02% | 154 | 0.08% | 919 | 0.1% |

| Yiddish | 61 847 | 40.0% | 15 377 | 7.37% | 19 398 | 9.32% | 202 374 | 12.7% |

| Other | 682 | 0.4% | 89 | 0.06% | 155 | 0.10% | 1 119 | 0.1% |

| Total | 154 532 | 100% | 208 781 | 100% | 203 401 | 100% | 1 591 207 | 100% |

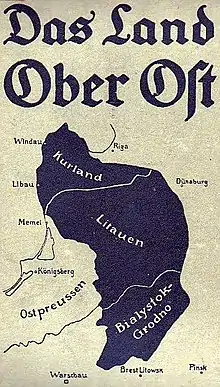

1916 German census

During World War I, all of modern-day Lithuania and Poland was occupied by the German Army. On 9 March 1916, the German military authorities organized a census to determine the ethnic composition of their newly conquered territories.[25] Many Belarusian historians note that the Belarusian minority is not noted among the inhabitants of the city.

| Nationality | 1 Nov 1915 | 9-11 Mar 1916 | 14 Dec - 10 Jan 1917 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poles | — | 70 629 | 50,15% | 74 466 | 53,65% |

| Jews | — | 61 265 | 43,50% | 57 516 | 41,44% |

| Belarusians | — | 1 917 | 1,36% | 611 | 0,44% |

| Lithuanians | — | 3 699 | 2,63% | 2 909 | 2,10% |

| Russians | — | 2 080 | 1,48% | 2 212 | 1,59% |

| Germans | — | 1 000 | 0,71% | 880 | 0,63% |

| Other | — | 300 | 0,21% | 193 | 0,14% |

| Overall | 142 063 | 140 840 | 138 787 | ||

The census was organised by Oberbürgermeister Eldor Pohl. Representatives of local population were included in the commission. Poles were represented by Jan Boguszewski, Feliks Zawadzki and Władysław Zawadzki, Jews by Nachman Rachmilewicz, Simon Rosenbaum and Zemach Shabad, Lithuanians by Antanas Smetona, Aleksandras Stulginskis and Augustinas Janulaitis. Belarusians did not have any representation.[26] Each member of the commission was responsible for the census in one of the nine parts into which the city was divided, and was accompanied by two representatives of other nationalities. As a result each part of the city was entrusted to commission consisted of one Pole, Jew and Lithuanian.[27] Each commission had an ethnically mixed team of clerks at their disposal. Overall 425 of them were engaged in carrying out the census; 200 of them were Jews, 150 Poles, 50 Lithuanians and 25 Belarusians.[27] Yet it didn't stop many Lithuanians from complaining that many of the clerks employed in carrying out the census were Polish citizens of Germany, mainly from Poznań, so the results of the census were unreliable.[28]

Census itself was carried out in days 9–11 March, for 5 more days people were able to correct their declarations and make complaints.[29] The main complain was that many of the clerks, mainly Jewish ones, did not know any other language other than Yidish or Russian, often also didn't know latin script, which in effect let to many mistakes, also many people simply refused to answer the questions they didn't understand.[30] There were also instances when for political reasons people were registered as belonging to different nationality than they declared.[31] Overall according to census city was inhabited by 140 480 people, 76 196 of them were Roman Catholics (54,10%), 70 692 were Polish (50,15%). The second group were Jews, 61 265 declared such nationality (43,5%) and 61 233 declared Judaism as their religion (43,47%).[32] The population of the city deacreased from 205 300 in 1909 to just 140 800 registered in the new census. Almost all of Russians left the city with the army, their percentage shrinked from 20% in 1909 to just 1,46% now.[33]

In comparison with the first Germans census (carried out in November 1915, wasn't asking about nationality), the number of inhabitants decreased by 1 223 from 142 063.[34] The most striking result was the difference in the number of inhabitants and the number of people registered for food ration stamps. According to responsible office in March 1916 there was 170 836 people in the city eligible to receive food rations, which gave the difference of about 18%.[35] German authorities alarmed by the results reformed the rationing system and in October the number of stamps was reduced so the number of registered persons decreased to 142 218.[36] Given people were rather leaving Vilnius — refugees were going back to their homes, people were trying to find better life conditions in the countryside — the numbers were still most likely inflated.[36] In a result Germans decided to carry out additional census.

Every inhabitant of Vilnius was ordered to appear in the right office with a passport and a ration card. In front of ethnically mixed commission he needed to declare his and his family nationality and religion, and also declare the number of people in the household. After that he was given a new ration card where such informations were included. Results were even more favourable for Poles, their number increased to 74 466 (53,65%), while the overall number of people in the city decreased to 138 787.[37]

Area Nationality |

City of Wilna[38] | Wilna county[39][40]

(no city) |

Occupied Lithuania/ Ober OstA[39][41] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belarusians | 1 917 | 1.4% | 559 | 0.9% | 60 789 | 6.4% |

| Lithuanians | 3 699 | 2.6% | 2 713 | 4.3% | 175 932 | 18.5% |

| Poles | 70 629 | 50.2% | 56 632 | 89.8% | 552 401 | 58.0% |

| Russians | 2 030 | 1.4% | 290 | 0.5% | 12 121 | 1.2% |

| Jews | 61 265 | 43.5% | 2 711 | 4.3% | 139 716 | 14.7% |

| Other | 1 300 | 1.0% | – | – | – | – |

| Total | 140 840 | 100% | 63 076 | 100% | 950 899 | 100% |

AData collected from the following districts (Kreise): Suwałki, Augustów, Sejny, Grodno, Grodno-city, Płanty, Lida, Radun, Vasilishki, Vilnius-city, Vilnius, Širvintos, Pabradė, Merkinė, Molėtai, Kaišiadorys, and Švenčionėliai.[39][41]

A similar census was organized for all of the territories of German-occupied Lithuania, and the northern border of the territory was more or less correspondent to that of present-day Lithuania; however, its southern border ended near Brest-Litovsk, and included the city of Białystok.

1921–1923 Polish census

The Peace of Riga, which ended the Polish–Soviet War, determined Poland's eastern border. In 1921, the first Polish census was held in territories under Polish control. However, Central Lithuania, seized in 1920 by General Lucjan Żeligowski's forces after a staged mutiny, was outside of de jure Poland. Poland annexed the short-lived state on 22 March 1922.

As a result, the Polish census of 20 September 1921 covered only parts of the future Wilno Voivodeship area, that is the communes of Breslauja, Duniłowicze, Dysna and Vileika.[42] The remaining part of the territory of Central Lithuania (that is the communes of Vilnius, Ašmena, Švenčionys and Trakai) was covered by the additional census organised there in 1923. The tables on the right give the combined numbers for Wilno Voivodeship's area (Administrative Area of Wilno), taken during both the 1921 and 1923 censuses. It is known that Lithuanians were forced to declare their nationality as Polish.[43]

Source: 1921–1923 Polish census[44]

Area Nationality |

City of Wilno 1923[38] | Administrative Area of Wilno | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belarusians | 3 907 | 2.3% | – | 25.7% |

| Lithuanians | 1 445 | 0.9% | – | – |

| Poles | 100 830 | 60.2% | – | 57.9% |

| Russians | 4 669 | 2.8% | – | – |

| Jews | 56 168 | 33.5% | – | 8.1% |

| Other | 435 | 0.26% | – | 8.3% |

| Total | 167 454 | 100% | – | 100% |

Polish census of 1931

The 1931 Polish census was the first Polish census to measure the population of the whole Wilno and Wilno Voivodeship at once. It was organised on 9 December 1931 by the Main Statistical Office of Poland. However, in 1931 the question of nationality was replaced by two separate questions of religion worshipped and the language spoken at home.[45] Because of that, it is sometimes argued that the "language question" was introduced to diminish the number of Jews, some of whom spoke Polish rather than Yiddish or Hebrew.[45] The table on the right shows the census findings on language. Wilno voivodeship did not include Druskininkai area and included just a small part of Varėna area where the majority of inhabitants were Lithuanians. Even then, some Lithuanians were recorded as belonging to the Polish nationality.[43] The voivodeship, however, included Brelauja, Dysna, Molodečno, Ašmena, Pastovys and Vileika counties which now belong to Belarus.

In stark contrast to the Polish interwar censuses, the Vilnius region was the site of 30 Lithuanian Kindergartens, 350 Lithuanian Primary schools, 2 Lithuanian gymnasiums and a Lithuanian teacher's seminary, all of which indicate that there were far more Lithuanians in the Vilnius region than the censuses accounted for.[3]

Area Language |

City of Wilno | Wilno-Troki county

(no city) |

Wilno and the

Wilno-Troki county |

Wilno

voivodeship | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belarusian | 1 700 | 0.9% | 5 549 | 2.6% | 7 286 | 1.8% | 289 675 | 22.7% |

| German | 561 | 0.3% | 171 | 0.1% | 732 | 0.2% | 1 357 | 0.1% |

| Lithuanian | 1 579 | 0.8% | 16 934 | 7.9% | 18 513 | 4.5% | 66 838 | 5.2% |

| Polish | 128 628 | 65.9% | 180 546 | 84.2% | 309 174 | 75.5% | 761 723 | 59.7% |

| Russian | 7 372 | 3.8% | 3 714 | 1.7% | 11 086 | 2.7% | 43 353 | 3.4% |

| Yiddish and Hebrew | 54 596 | 28.0% | 6 508 | 3.0% | 61 104 | 14.9% | 108 828 | 8.5% |

| Other | 598 | 0.3% | 1 050 | 0.5% | 1 648 | 0.4% | 4 165 | 0.3% |

| Total | 195 071 | 100% | 214 472 | 100% | 409 543 | 100% | 1 275 939 | 100% |

Lithuanian census of 1939

Lithuanians troops who entered Vilnius in 1939 had to resort to French and German to communicate with the city's inhabitants. According to the official Lithuanian data from 1939, Lithuanians made up 6% of Vilnius population.[47] A Lithuanian sanitary platoon didn't find any Lithuanian-speaking villages despite traveling for two weeks in the surrounding countryside.[48] In December 1939, shortly after the return of Lithuanian control to what it claimed was its capital city, the Lithuanian authorities organized a new census in the area. However, the census is often criticized as skewed, intending to prove Lithuania's historical and moral rights to the disputed area rather than determine the factual composition.[49] Lithuanian figures from that period are criticized as significantly inflating the number of Lithuanians.[50] People receiving Lithuanian citizenship were pressured to declare their nationality as being Lithuanian rather than Polish.[48]

German-Lithuanian census of 1942

After the outbreak of the German-Soviet War in 1941, the area of eastern Lithuania was quickly seized by the Wehrmacht. On 27 May 1942 a new census was organised by the German authorities and the local Lithuanian collaborators.[51] The details of the methodology used are unknown and the results of the census are commonly believed to be an outcome of the racial theories and beliefs of those who organised the census rather than the actual ethnic and national composition of the area.[51] Among the most notable features is a complete lack of data on the Jewish inhabitants of the area (see Ponary massacre for explanation) and a much lowered number of Poles, as compared to all the earlier censuses.[52][53] However, Wilna-Gebiet did not include Breslauja, Dysna, Maladečina, Pastovys and Vileika counties but included Svieriai district. That explains the decline in the number of Belarusians in Wilna-Gebiet.

Area Nationality |

City of Wilna | Wilna county | Wilna city

and county | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belarusians | 5 348 | 2.55% | 9 735 | 6.36% | 15 083 | 4.16% |

| Germans | 524 | 0.25% | 168 | 0.11% | 692 | 0.19% |

| Lithuanians | 51 111 | 24.37% | 66 048 | 43.15% | 117 159 | 32.29% |

| Poles | 87 855 | 41.89% | 71 436 | 46.67% | 159 291 | 43.91% |

| Russians | 4 090 | 1.95% | 1 684 | 1.10% | 5 774 | 1.59% |

| Jews | 58 263 | 27.78% | 3 505 | 2.29% | 61 768 | 17.03% |

| Other | 2 538 | 1.21% | 490 | 0.32% | 3 028 | 0.83% |

| Total | 209 729 | 100% | 153 066 | 100% | 362 795 | 100% |

Area Nationality |

City of Wilna | Wilna county

(no city) |

Wilna city

and county |

Wilna-Land

and city | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belarusians | 3 029 | 2.11% | 5 998 | 4.00% | 9 027 | 3.07% | 80 853 | 10.87% |

| Germans | 476 | 0.33% | 52 | 0.03% | 528 | 0.18% | 771 | 0.10% |

| Lithuanians | 29 480 | 20.54% | 73 752 | 49.13% | 103 232 | 35.17% | 310 449 | 41.75% |

| Poles | 103 203 | 71.92% | 67 054 | 44.67% | 170 257 | 57.99% | 324 750 | 43.67% |

| Russians | 6 012 | 1.95% | 2 713 | 1.81% | 8 725 | 2.97% | 23 222 | 3.12% |

| Jews | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Latvians | 78 | 0.05% | 19 | 0.01% | 97 | 0.03% | 182 | 0.02% |

| Other | 1 220 | 0.37% | 515 | 0.20% | 1 735 | 0.59% | 3 452 | 0.46% |

| Total | 143 498 | 100% | 150 105 | 100% | 293 601 | 100% | 743 582 | 100% |

Soviet data from 1944 to 1945

Vilnius' registered population was about 107,000. People who moved to the city during the German occupation, military personnel, and temporary residents were not included in the population count. According to the data from the beginning of 1945, the total population of Vilnius, Švenčionys and Trakai districts amounted to 325,000 people, half of them Poles.[56] About 90% of the Vilnius Jewish community had perished in the Holocaust. All Vilnius Poles were required to register for resettlement, and about 80% of them were relocated to Poland.[57]

Soviet census of late 1944-early 1945:A[58]

Area Nationality |

City of Vilnius | Vilnius district | Trakai district | Švenčionys district | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belarusians | 2 062 | 1.9% | 800 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Lithuanians | 7 958 | 7.5% | 7 500 | – | ~70 000 | – | 69 288 | – |

| Poles | 84 990 | 79.8% | 105 000 | – | ~40 000 | – | 19 108 | – |

| Russians | 8 867 | 8.3% | 2 600 | – | ~3 500 | – | 2 542 | – |

| Ukrainians | ~500[56] | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Jews | ~1 500[56] | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Total | 106 497 | 100% | 115 900 | 100% | ~114 000 | 100% | 93 631 | 100% |

AIn the Trakai and Švenčionys districts, a certain number of Belarusians was included into the categories of Russians and Poles.[58]

Soviet census of 1959

During the 1944-1946 period, about 50% of the registered Poles in Lithuania were transferred to Poland. Dovile Budryte estimates that about 150,000 people left the country.[59] During 1955–1959 period, another 46,600 Poles left Lithuania. However, Lithuanian historians estimate that about 10% of people who left for Poland were ethnic Lithuanians. While the removal of Poles from Vilnius constituted a priority for the Lithuanian communist authorities, the depolonization of the countryside was limited due to the concerns of depopulation and agricultural labour force deficit. The population transfers and migration processes resulted in the formation of territorial ethnic segregation, with Lithuanians and Russians prevailing in Vilnius and Poles predominating in the city's surroundings.[60][61]

These are the results of the migration to Poland and the growth of the city due to industrial development and the Soviet Union policy.

1959 Soviet census:

Area Nationality |

City of Vilnius[57][62] | Vilnius Region | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belarusians | 14 700 | 6.2% | – | – |

| Lithuanians | 79 400 | 33.6% | – | – |

| Poles | 47 200 | 20.0% | – | – |

| Russians | 69 400 | 29.4% | – | – |

| Tatars | 496 | 0.2% | – | – |

| Ukrainians | 6 600 | 2.8% | – | – |

| Jews | 16 400 | 7.2% | – | – |

| Other | – | 0.8% | – | – |

| Total | 236 100 | 100% | – | – |

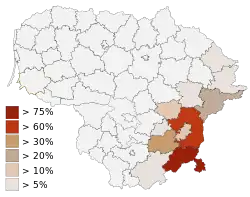

Soviet census of January 1989

Poles accounted for 63.6% of the population in Vilnius rayon/county (currently Vilnius district municipality, excluding the city of Vilnius itself), and 82.4% of the population in Šalčininkai rayon/county (currently known as Šalčininkai district municipality).[63]

Area Nationality |

City of Vilnius[62] | Vilnius Region | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belarusians | – | 5.3% | – | – |

| Lithuanians | – | 50.5% | – | – |

| Poles | – | 18.8% | – | – |

| Russians | – | 20.2% | – | – |

| Tatars | – | 0.2% | – | – |

| Ukrainians | – | 2.3% | – | – |

| Jews | – | 1.6% | – | – |

| Other | – | 1.1% | – | – |

| Total | 582 500 | 100% | – | – |

Lithuanian census of 2001

2001 Lithuanian census:[64]

Area Nationality |

Vilnius city municipality[57][62] | Vilnius district municipality | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belarusians | 22 555 | 4.1% | 3 869 | 4.4% |

| Lithuanians | 318 510 | 57.5% | 19 855 | 22.4% |

| Poles | 104 446 | 18.9% | 54 322 | 61.3% |

| Russians | 77 698 | 14.0% | 7 430 | 8.4% |

| Ukrainians | 7 159 | 1.3% | 619 | 0.7% |

| Jews | 2 785 | 0.5% | 37 | <0.01% |

| Other | 2 528 | 0.5% | 484 | 0.5% |

| Total | 553 904 | 100% | 88 600 | 100% |

Lithuanian census of 2011

Area Nationality |

Vilnius city municipality[65] | Vilnius district municipality[65] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belarusians | 18 924 | 3.5% | 3 982 | 4.2% |

| Lithuanians | 338 758 | 63.2% | 30 967 | 32.5% |

| Poles | 88 408 | 16.5% | 49 648 | 52.1% |

| Russians | 63 991 | 11.9% | 7 638 | 8.0% |

| Ukrainians | 5 338 | 1.0% | 623 | 0.7% |

| Jews | 2 026 | 0.4% | 109 | 0.1% |

| Other | 4 754 | 0.9% | 754 | 0.8% |

| Not indicated | 13 432 | 2.5% | 1 627 | 1.6% |

| Total | 535 631 | 100% | 95 348 | 100% |

Jews of Vilnius

The Jews living in Vilnius had their own complex identity, and labels of Polish Jews, Lithuanian Jews or Russian Jews are all applicable only in part.[66] The majority of the Yiddish speaking population used the Litvish dialect.

The situation today

The Vilnius urban region is the only area in East Lithuania that doesn't face a decrease in population density. Polish people constitute the majority of native rural inhabitants in the Vilnius region. However, the share of Poles across the region is dwindling mainly due to the natural decline of rural population and process of suburbanization – most of new residents in the outskirts of Vilnius are Lithuanians.[61]

Most Poles in the area today speak a dialect known as the simple speech (po prostu).[67] Colloquial Polish in Lithuania includes dialectic qualities and is influenced by other languages.[68] Educated Poles speak a language close to standard Polish.

See also

References

- ↑ Antoniewicz 1930, p. 122.

- ↑ Šapoka 1962, p. 58.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Budreckis 1967.

- 1 2 Zinkevičius 2014.

- 1 2 Martinkėnas 1990, p. 25.

- ↑ Nitsch, Kazimierz; Otrębski, Jan (1931). "Język Polski. 1931, nr 3 (maj/czerwiec)" (in Polish). Polska Akademia Umiejętności, Komisja Języka Polskiego: 80–85. Retrieved 3 November 2023.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Martinkėnas, Vincas (19 December 2016). "Vilniaus ir jo apylinkių čiabuviai". Alkas.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 3 November 2023.

- ↑ "Jankowiak: "Mowa prosta" jest dla mnie synonimem gwary białoruskiej". 26 August 2015.

- ↑ Miller 2008, pp. 70, 81–82.

- ↑ Lukowski & Zawadzki 2006, p. 195.

- ↑ Geifman 1999, p. 116.

- ↑ Roshwald 2001, p. 24.

- ↑ Tomas Venclova, Four Centuries of Enlightenment. A Historic View of the University of Vilnius, 1579–1979, Lituanus, Volume 27, No.1 – Summer 1981

- ↑ Rev. Stasys Yla, The Clash of Nationalities at the University of Vilnius, Lituanus, Volume 27, No.1 – Summer 1981

- ↑ Ronald Grigor Suny, Michael D. Kennedy, "Intellectuals and the Articulation of the Nation", University of Michigan Press, 2001, pg. 265

- ↑ The genealogical tree of Józef Klemens (Ziuk) Piłsudski

- ↑ Maliszewski, Edward (1916). Polskość i Polacy na Litwie i Rusi (in Polish) (2nd ed.). PTKraj. pp. 13–14.

- ↑ (in Polish) Piotr Łossowski, Konflikt polsko-litewski 1918–1920 (The Polish–Lithuanian Conflict, 1918–1920), Warsaw, Książka i Wiedza, 1995, ISBN 83-05-12769-9, pp. 11.

- ↑ Egidijus Aleksandravičius; Antanas Kulakauskas (1996). Carų valdžioje: Lietuva XIX amžiuje (Lithuania under the reign of Czars in the 19th century) (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Baltos lankos. pp. 253–255.

- ↑ Wiesław Łagodziński, ed. (2002). 213 lat spisów ludności w Polsce 1789–2002 (in Polish). Główny Urząd Statystyczny, Warsaw.

- ↑ "Vilnius district – the city of Vilnius".

- ↑ "Vilnius district without urban population".

- ↑ "Traka district – total population".

- ↑ "Vilnius governorate – total population".

- ↑ Michał Eustachy Brensztejn (1919). Spisy ludności m. Wilna za okupacji niemieckiej od. 1 listopada 1915 r. (in Polish). Biblioteka Delegacji Rad Polskich Litwy i Białej Rusi, Warsaw.

- ↑ Brensztejn 1919, p. 6

- 1 2 Brensztejn 1919, p. 7

- ↑ Balkelis 2018, p. 29

- ↑ Brensztejn 1919, p. 13

- ↑ Brensztejn 1919, p. 15

- ↑ Brensztejn 1919, p. 15-19

- ↑ Brensztejn 1919, p. 21

- ↑ Pukszto 2000, p. 26

- ↑ Brensztejn 1919, p. 5

- ↑ Brensztejn 1919, p. 22; In May 1915 the number was even bigger — 172 832 people were registered

- 1 2 Brensztejn 1919, p. 23

- ↑ Brensztejn 1919, p. 24

- 1 2 Rocznik Statystyczny Wilna 1937 (in Polish and French). Centralne Biuro Statystyczne. 1939. p. 9.

- 1 2 3 Wielhorski 1947, p. 59.

- ↑ Jurkiewicz 2010.

- 1 2 Srebrakowski, Aleksander (2001). Polacy w Litewskiej SSR (in Polish). Adam Marszałek. p. 30. ISBN 83-7174-857-4.

- ↑ Ludwik Krzywicki (1922). "Organizacja pierwszego spisu ludności w Polsce". Miesięcznik Statystyczny (in Polish). V (6).

- 1 2 Astas, Vydas (11 July 2008). "Kaip gyvuoji, Vilnija?" [How do you live, Vilnija?]. Literatūra ir menas (in Lithuanian). 14. ISSN 1392-9127.

Yra užfiksuota daugybė atvejų apie prievartinį lietuvių užrašymą lenkais Vilniaus okupacijos, Armijos Krajovos siautėjimo ir žiauriuoju sovietinio laikotarpiu. Tai vyko masiškai.

- ↑ Ludwik Krzywicki (1922). "Rozbiór krytyczny wyników spisu z dnia 30 IX 1921 r". Miesięcznik Statystyczny (in Polish). V (6).

- 1 2 Joseph Marcus (1983). Social and political history of the Jews in Poland, 1919–1939. Walter de Gruyter. p. 17. ISBN 978-90-279-3239-6. Retrieved 5 March 2011.

- ↑ "Drugi Powszechny Spis Ludności z dnia 9 XII 1931 r". Statystyka Polski (in Polish). D (34). 1939.

- ↑ Snyder, Tymothy (2002). "Memory of sovereignty and sovereignty over memory: Poland, Lithuania and Ukraine, 1939–1999". In Müller, Jan-Werner (ed.). Memory and Power in Post-War Europe: Studies in the Presence of the Past. Cambridge University Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0521806107.

- 1 2 Voren, Robert van (2011). Undigested Past: The Holocaust in Lithuania. Rodopi. p. 23. ISBN 9789042033719.

- ↑ Zakład Wydawnictw Statystycznych (1990). Concise Statistical Year-Book of Poland: September 1939 – June 1941. Zakład Wydawnictw Statystycznych. ISBN 83-7027-015-8.

- ↑ Ghetto In Flames. KTAV Publishing House, Inc. pp. 27–. GGKEY:48AK3UF5NR9. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- 1 2 A. Srebrakowski (1997). Liczba Polaków na Litwie według spisu ludności z 27 maja 1942 roku (in Polish). Wrocław University, Wrocławskie Studia Wschodnie.

- ↑ Główny Urząd Statystyczny (1939). Mały rocznik statystyczny 1939 (in Polish). Główny Urząd Statystyczny, Warsaw.

- ↑ Stanisław Ciesielski; Aleksander Srebrakowski (2000). "Przesiedlenie ludności z Litwy do Polski w latach 1944–1947". Wrocławskie Studia Wschodnie (in Polish) (4): 227–53. ISSN 1429-4168. Archived from the original on 17 October 2002.

- ↑ Srebrakowski 1997, p. 173.

- ↑ Srebrakowski 1997, p. 176-182.

- 1 2 3 Vitalija Stravinskiene. Polska ludność Litwy Wschodniej i Południowo-Wschodniej w polu widzenia sowieckich służb bezpieczeństwa w latch 1944–1953. Instytut Historii Litwy. "Biuletyn Historii Pogranicza". Vol 11. 2001. p. 62.

- 1 2 3 Timothy Snyder. The Reconstruction of Nations. Yale University Press. 2003. pp. 91–93, 95

- 1 2 Stravinskienė, Vitalija (2015). "Between Poland and Lithuania: Repatriation of Poles from Lithuania, 1944-1947". In Bakelis, Tomas; Davoliūtė, Violeta (eds.). Population Displacement in Lithuania in the Twentieth Century. Experiences, Identities and Legacies. Vilnius Academy of Art Press. p. 233. ISBN 978-609-447-181-0.

- ↑ Dovile Budryte, Taming nationalism?: political community building in the post-Soviet Baltic States, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2005, ISBN 0-7546-4281-X, Google Print, p.147

- ↑ Theodore R. Weeks. "Remembering and forgetting: creating Soviet Lithuanian capital Vilnius 1944–1949." In: Jorg Hackmann, Marko Lehti. Contested and Shared Places of Memory: History and politics in North Eastern Europe. Routledge. 2013. pp. 139–141.

- 1 2 Burneika, Donatas; Ubarevičienė, Rūta (2013). "The Impact of Vilnius City on the Transformation Trends of the Sparsely Populated EU East Border Region" (PDF). Etniškumo studijos/Ethnicity Studies (2): 50, 58–59.

The repatriation from the rural areas, according to Czerniakievicz and Cerniakiewicz (2007), was limited because of the fear of the Lithuanian SSR administration that the depopulation and labour force shortage might start there. This led to the emergence of the ethnic segregation in the Vilnius region. The sharp ethnic contrast between the central city and its surroundings remained evident down to the recent days (...) in the Vilnius region the absolute majority of native rural population are Poles.

- 1 2 3 Saulius Stanaitis, Darius Cesnavicius. Dynamics of national composition of Vilnius population in the 2nd half of the 20th century. Bulletin of Geography, Socio-Economic Series. No. 13/2010. pp. 35–37.

- ↑ Piotr Eberhardt. Ethnic Groups and Population Changes in Twentieth-century Central-Eastern Europe: History, Data, and Analysis. M.E. Sharpe. 2003. p. 59.

- ↑ Population by some ethnicities by county and municipality. Data from Statistikos Departamentas, 2001 Population and Housing Census. Archived 29 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 Census 2011 Archived 1 August 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Statistics Lithuania, 2013

- ↑ Ezra Mendelsohn, On Modern Jewish Politics, Oxford University Press, 1993, ISBN 0-19-508319-9, Google Print, p.8 and Mark Abley, Spoken Here: Travels Among Threatened Languages, Houghton Mifflin Books, 2003, ISBN 0-618-23649-X, Google Print, p.205

- ↑ Lietuvos rytai; straipsnių rinkinys The east of Lithuania; the collection of articles; V. Čekmonas, L. Grumadaitė "Kalbų paplitimas Rytų Lietuvoje" "The distribution of languages in eastern Lithuania"

- ↑ K. Geben, Język internautów wileńskich (The language of Vilnius Internauts), in Poradnik Jezykowy, 2008 Archived 18 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

Sources

- Anisimov, Vladimir Ilyich (1912). "Виленская губерния" [Vilna province]. Энциклопедический словарь Русского библиографического института Гранат (in Russian). Vol. 10: Вех — Воздух. Moscow: Изд. тов. А. Гранат и К°.

- Antoniewicz, Włodzimierz (1930). "Czasy przedhistoryczne i wczesnodziejowe Ziemi Wileńskiej". Wilno i Ziemia Wilenska (in Polish). Vol. I. Polska Drukarnia Nakładowa "LUX" Ludwika Chomińskiego. pp. 103–123.

- Brensztejn, Michał (1919). Spisy ludności m. Wilna za okupacji niemieckiej od d. 1 listopada 1915 r. (in Polish). Warsaw.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Budreckis, Algirdas (1967). "Etnografinės Lietuvos rytinės ir pietinės sienos". Karys.

- Dolbilov, Mikhail (2010). Русский край, чужая вера: Этноконфессиональная политика империи в Литве и Белоруссии при Александре II [Russian Territory, Foreign Faith: Ethno-Confessional Policy of the Empire in Lithuania and Belarus under Alexander II] (in Russian). Moscow: Новое литературное обозрение. ISBN 978-5-86793-804-8.

- Eidintas, Alfonsas; Bumblauskas, Alfredas; Kulakauskas, Antanas; Tamošaitis, Mindaugas (2013). The History of Lithuania (PDF). Vilnius: Eugrimas. ISBN 978-609-437-163-9.

- Geifman, Anna (1999). Russia Under the Last Tsar: Opposition and Subversion, 1894–1917. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 1-55786-995-2.

- Jurkiewicz, Joanna Januszewska (2010). Stosunki narodowościowe na Wileńszczyźnie w latach 1920—1939 (in Polish). Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego.

- Kleczyński, Józef (1892). Spisy ludności w Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej. Akademia Umiejętności, Kraków.

- Kleczyński, Józef (1898). Poszukiwania spisów ludności Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej w zbiorach Moskwy, Petersburga i Wilna. Kraków: Akademia Umiejętności.

- "Lietuvos Statistikos Metraštis". Lietuvos Statistikos Metrastis: Statistical Yearbook of Lithuania. Lietuvos Statistikos Departamentas prie Lietuvos Respublikos Vyriausybės. 1995. ISSN 1392-026X.

- Lukowski, Jerzy; Zawadzki, Hubert (2006). A concise history of Poland. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521853323.

- Martinkėnas, Vincas (1990). Vilniaus ir jo apylinkių čiabuviai (in Lithuanian). Vilnius.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Miller, Alekseĭ I. (2008). "Identity and loyalty in the language policy of the Romanov Empire at her Western Borderland". The Romanov Empire and Nationalism: Essays in the Methodology of Historical Research. Central European University Press.

- Pierwsze dziesięciolecie Głównego Urzędu Statystycznego. Vol. 3, Organizacja i technika opracowania pierwszego polskiego spisu powszechnego z 30 września 1921 roku. Warsaw: Główny Urząd Statystyczny. 1930.

- Roshwald, Aviel (2001). Ethnic Nationalism and the Fall of Empires: Central Europe, Russia and the Middle East, 1914–1923. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-17893-2.

- Rutowski, Tadeusz, ed. (1888). Rocznik Statystyki Przemysłu i Handlu Krajowego. Lwów: Krajowe Biuro Statystyczne.

- Šapoka, Adolfas (1962). Vilnius in the Life of Lithuania. Toronto.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Skarbek, Jan, ed. (1996). Mniejszości w świetle spisów statystycznych XIX-XX w. Lublin: Instytut Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej. ISBN 83-85854-16-9.

- Srebrakowski, Aleksander (1997). Liczba Polaków na Litwie według spisu ludności z 27 maja 1942 roku (in Polish). Wrocław University, Wrocławskie Studia Wschodnie.

- Strzelecki, Zbigniew, ed. (1991). Polish Population Review. Polish Demographic Society, Central Statistical Office. ISSN 0867-7905.

- Strzelecki, Zbigniew; Toczyński, Tadeusz; Latuch, Kazimierz, eds. (2002). Spisy ludności Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej 1921–2002; wybór pism demografów. Warsaw: Polskie Towarzystwo Demograficzne, Główny Urząd Statystyczny. ISBN 83-901912-9-6.

- Wielhorski, Władysław (1947). Polska a Litwa. Stosunki wzajemne w biegu dziejów [Poland and Lithuania. Mutual relations in the course of history] (in Polish). The Polish Research Centre.

- Zinkevičius, Zigmas (28 January 2014). "Lenkiškai kalbantys lietuviai" [Polish-speaking Lithuanians] (in Lithuanian).

External links

- Theodore R. Weeks, From "Russian" to "Polish": Vilna-Wilno 1900–1925

- Lithuanian-Belarusian language boundary in the 4th decade of the 19th century

- Lithuanian-Belarusian language boundary at the beginning of the 20th century

- List of the 19th-century Suwałki region family names

- 1921 and 1931 censuses (DOC), HTML

- Repatriation and Resettlement of Ethnic Poles

- std.lt 2001 census (PDF) std.lt In English

- A. Srebrakowski, Zmiany struktury narodowościowej Wileńszczyzny w latach 1939–1947 (w:) Kresy Wschodnie II Rzeczypospolitej. Przekształcenia struktury narodowościowej 1931–1948, Pod redakcją Stanisława Ciesielskiego, Wrocław 2006, s. 47–54 Archived 18 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- A. Srebrakowski, The nationality panorama of Vilnius, Studia z Dziejów Rosji i Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej, Vol 55, No 3 (2020)

- [ vilniaus-r.lt]