Emil Preetorius (June 21, 1883 - January 27, 1973) was a German illustrator and graphic artist. He is considered one of the most important stage designers of the first half of the 20th century.

Life and career

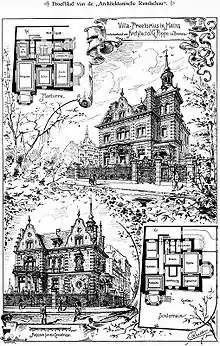

Emil Preetorius was born in Mainz. He studied law, art history and natural sciences in Munich, Berlin and Giessen, where he was awarded a doctorate. He then attended the Munich School of Applied Arts for a short time, but mainly trained himself as a painter and draftsman.[1] In 1909 he founded the school for illustration and book trade in Munich together with Paul Renner, headed the Munich training workshops from 1910 and became head of a class for illustration and a class for stage art at the University of Fine Arts in Munich in 1926, at which he became a Professor in 1928. In 1914 Preetorius, Franz Paul Glass, Friedrich Heubner, Carl Moos, Max Schwarzer, Valentin Zietara founded the artist association "Die Sechs", one of the first artist groups for the marketing of advertising orders, especially posters.

Preetorius created illustrations for numerous fiction works from 1908. He belonged to the circle of friends of Thomas Mann, and designed the book covers for the novella A Man and his Dog, and the 1954 novel Confessions of Felix Krull. Preetorius also designed the cover to the first public issue of Heinrich Mann's novel The Subject (1918). Preetorius worked for the Munich Kammerspiele from 1923.

Relationship with the Wagner family (1932-1942)

In 1932 Preetorius became the stage director of the Bayreuth Festival.

In 1941 Preetorius with the help of both Winifred Wagner and Heinz Tietjen attempted to help a Dutch Jew who had been head of the Wagner Society of Amsterdam[2] but the following year Preetorius was denounced to the Gestapo as "philo-Semitic" or “Jew friend”. Officially, his accuser was Dr. Gk, namely Herbert Gerigk, the head of the Music Directorate in the Office of the Fuhrer's Commissioner for the supervision of the entire intellectual and ideological training and education of the NSDAP (OFCS), and the co-editor of the notorious Lexicon of Jews in Music: but Preetorius always suspected that someone else was his real accuser. Wieland Wagner, the oldest son of Siegried and Winifred, and the grandson of the composer Richard Wagner, had for some time been attempting to claim what he regarded as his rightful inheritance, namely the artistic directorship of the Festival. Wieland was Hitler's favourite of Winifred's children and in order to ensure that Wieland would one day become the Festival's director, Hitler had exempted Wieland, along with 24 other young men, from military conscription. Others that were considered "divinely blessed" included the tenor Peter Anders, the stage designer Ulrich Roller, and the composer Gottfried Muller.[3] Preetorius was briefly held in Gestapo detention, and interrogated, his house was searched and his mail opened. It was discovered that Preetorius had been corresponding on friendly terms with Jews in Holland. Preetorius was initially forbidden to work, and declared an 'enemy of the State' by Gauletier Paul Giesler of Munich.[4] He later described the terror of the experience:

All the terrible things I’ve been through, with vaults crashing down, cellars reduced to rubble and people dying in agony - none of that compares with interrogation by the Gestapo...being so completely helpless, so defenceless against those horrible people is so paralysing that I suddenly understood how in such a situation you could give in and start “confessing”.[5]

Preetorius presented a difficult case for the Munich authorities: as well as his closeness to Winifred and Tietjen, Preetorius was also ranked by Hitler as one of the most important set designers in Germany. Brigitte Hamannn argues that the intervention that led to Preetorius' reprieve was made by Hermann Goering, initiated by Tietjen. When the Munich authorities contacted Hitler asking what to do with this enemy of the state Hitler played the whole situation down and decided that Preetorius should be freed and that he could continue to work despite his attitude.[6] Preetorius, however, did not return to Bayreuth and he didn't enter the Festpielhaus for ten years. He always suspected that Wieland was the Gestapo informer and his real accuser. Writing fifty years after the event Wolfgang Wagner, writing in his autobiography, reflected that if Alfred Roller had 'been well enough to collaborate at Bayreuth on a long-term basis, the personal and artistic altercations between Wieland and Preetorius would never have occurred.'[7]

Winifred's denazification

Wieland's animosity towards, and fear[8] of Preetorius later threatened the liberty of his mother, Winifred. Winifred had been an early supporter of Hitler and she and her husband had travelled to Munich to witness the 1923 putsch. There were rumours at the time of her denazification trial (Spruchkammer) that she had been Hitler's lover: she feared being classified as a major offender (Hauptschuldige) and expected to be sentenced to prison or a labour-camp.[9] The court trial opened on 25 June 1947. In her defence she had amassed fifty four written testimonies detailing how she had engaged with those who had been persecuted and deprived of their rights by the Nazis. Additionally, thirty witnesses were present[10] to provide evidence of her kind deeds and "pure humanity".[11] Yet despite having been asked, Preetorius declined to either attend or provide a written statement. Preetorius had never received the artistic recognition for his achievements at Bayreuth that he regarded was his due. His bitterness now erupted in his reply to Winifred's appeal:-

I don't want to meet your children again, none of whom treated me very well; Wieland in particular was positively hostile, treacherous, even contemptuous. And it's here, in respect of your children, that I'm afraid I may be forced to testify in a way that is not helpful to you. The incredible arrogance of your children - especially Wieland, who exploited his connections with Hitler and Bormann to get away with absolutely everything - that arrogance, lack of respect, and unwillingness to recognize anyone else's achievements, or give them their due at all - I'm so bitter about it, that I can't be sure I won't violently erupt and create an atmosphere not at all favourable to you...No, my dear Frau Wagner, for all my friendship towards you, please understand - I cannot come![12]

Winifred later, in Syberberg's 1975 film, described herself as "a madly loyal person...If I form an attachment to somebody, I maintain it through thick and thin...I stand by that person.[13] When Preetorius finally returned to Bayreuth, for the 1952 festival, Winifred, "threw herself upon my neck in tears".[14]

Post war years

During an Allied air-raid on Berlin in 1945 Preetorius' home was burnt to the ground in an air raid (Tietjen's house was also destroyed in the same air raid). The destruction of their respective homes concomitantly saw the loss of many papers associated with the history of the Wagner family.[15]

In 1951 Preetorius retired. From 1947 to 1961 Preetorius was a member of the Bavarian Senate. From 1948 to 1968 he was President of the Bavarian Academy of Fine Arts in Munich. From 1952 he was a member of the German Academy for Language and Poetry in Darmstadt. He was a member of the German Association of Artists.

He died in Munich and is buried in the Bogenhausener cemetery.[16]

Theatre

Bayreuth

In autumn 1929 Siegfried and Winifred Wagner travelled to the Berlin City Opera for the premiere of a production of Lohengrin staged and directed by its artistic director Heinz Tietjen with design by Preetorius. The orchestra was conducted by Wilhelm Furtwangler. Siegfried was particularly impressed by the musical impact of the chorus and crowd scenes that he recommended Tietjen to Winifred as a future artistic director of the Bayreuth Festival in association with Preetorius and Furtwangler.[17] The 1929 production marked, according to the Bayreuth historian Frederic Spotts, an advance in Wagnerian staging.[18]

1933 Festival

Preetorius's first stagings at Bayreuth were Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, and Der Ring des Nibelungen at the 1933 Festival.[19] In August 1933 Walter Legge was attending the Festival in his role as the music critic of the Manchester Guardian newspaper. As well as observing that the Wagner Festival had been transformed into a Hitler festival, with Mein Kampf displacing Mein Leben,[20] Legge heaped scorn on the quality of the conducting, a consequence of German musical protectionism. Legge was, however, unstinting in his praise for the stage designs:

Both the orchestral playing and the choral singing have been of the highest quality...These, together with the staging of Preetorius and Tietjen, have been the great delights of the festival. We in England accustomed to Covent Garden's badly painted cloths and inadequate stage machinery, and to the makeshift scenery of touring companies, have little idea of the advance in operatic staging that has taken place in Central Europe during the past twelve years. But even those who have watched with interest te development of Emil Preetorius as a scenic artist and Heinz Tietjen as a producer have been astonished by the dramatic strength and stark realism of these Bayreuth productions...For Preetorius and Tietjen give dramatic truth, and Wagnerian dramatic truth will outdo any other form of theatrical art.[21]

Other reviewers were similarly impressed. Hans Heinz Stuckenschmidt could scarcely believe his eyes. At a time when the cultural clock under National Socialism was being turned back he remarked that here, at Hitler's Festival,[22] were two productions 'with an entirely novel scenic dress, and executed in a fashion which departed completely from the Bayreuth tradition'.[23] Similarly, Ernest Newman was at first taken aback by the bare sets of the Ring but found that he 'soon became reconciled to their gauntness' and came to like them best when they eschewed the old naturalism.[24] Alfred Einstein had the highest praise for Preetorius finding the Meistersingers settings especially successful. Almost everything was in its place and 'yet everything is new and suggestive'.[25] When Preetorius's designs were less successful Einstein was more inclined to blame Wagner. Preetorius had, Einstein thought, compromised his art when attempting to be faithful to blame Wagner's poor stage instructions.[26] Despite the praise, and that his Valkyries's rock and Brünnhilde's fir tree became iconic, Preetorius was never completely content with his 1933 productions.[27]

The controversial productions launched onto the Bayreuth stage by Preetorius and Tietjen during the Third Reich, productions that were just as controversial as those staged in the post-war period by Wieland Wagner, demonstrates, it has been argued by Jens Malte Fischer, that artistic freedom continued to reign in Bayreuth despite the Nazi regime.[28]

Salzburg

In 1944, he made his debut as a set designer for the Richard Strauss premiere of Die Liebe der Danae at the Salzburg Festival. Preetorius' relocation from Bayreuth to Salzburg was not without political significance. Under the direction of the "non-Aryan" Max Reinhardt, Salzburg had become a sanctuary for artists displaced from Germany, and soon came to be seen as the "Jewish" counterpart of "German" Bayreuth.[29] Owing to the war-related theatre ban however, the production only came to a public rehearsal. The actual premiere of this production eventually took place in Salzburg in the summer of 1952.

In 1948 Preetorius designed the sets for Günther Rennert's Salzburg production of Beethoven's Fidelio with Wilhelm Furtwängler on the podium.

Asian Art collector

At the start of the twentieth century Preetorius developed a passionate interest in Asian art. He began to collect mostly visual art but also Japanese theatre masks, Persian ceramics, Chinese textiles and carpets, and miniatures from India. He collected for over half a century and by 1960 his collection had become one of the most important German collections of this genre.

In 1960 the bulk of the collection was purchased by the Free State of Bavaria whereby over six hundred objects were transferred to the, then, State Museum of Ethnology which is now the Museum Five Continents. This collection is known as "The Preetorius Collection 1960".[30]

After the sale Preetorius continued to collect Asian art with an especial focus on East Asian art. The collection areas include pictures, ceramics, wood, metal and textiles. Following the death of his widow, Lilli Preetorius, in 1997 this collection was inherited by the Preetorius Foundation (which was founded in 1978 to promote science and art in connection with the collection). The objects in this collection, known as "The Preetorius Collection 1997", are on permanent loan to the Museum Five Continents.[31]

Honours

1953: Great Cross of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany

Literary works

1938: From the stage design with Richard Wagner

1940: Thoughts on Art

1947: Weltbild und Weltgestalt tr. Worldview and world salary

1963: Mystery of the Visible

Illustrated books(selection)

1908: Adelbert von Chamisso : Peter Schlemihl's miraculous story

1909: Emil Lucka : Isolde Weisshand

1910: Alain-René Lesage : The Limping Devil

1911: Felix Schloemp : Laurel Wreath and Frill

1912: Jean Paul : Giannozzo's Airship's Sea Book

1912: Kurt Friedrich-Freksa : Phosphorus

1913: Alphonse Daudet : The Wonderful Adventures of Tartarin from Tarascon

1913: Ernst Elias Niebergall : Datterich

1914: Joseph von Eichendorff : From the life of a good-for-nothing

1914: Klabund : The German Soldier's Song

1915: Jean Paul: Life of the cheerful schoolmaster Wuz in Auenthal

1916: Claude Tillier : My Uncle Benjamin

1917: Friedrich Gerstäcker : Mr. Mahlhuber's travel adventure

1919: Thomas Mann : Herr und Hund, Ein Idyll

1919: ETA Hoffmann : The Elementalist

1920: Frank Wedekind : Lute Songs

Lithographic portfolio: sketches, portraits 1910–1919.

Notes

- ↑ "Preetorius, Emil". Vienna Secession: Art Nouveau in Vienna and Germany 1895-1918. vienna.secession.com. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- ↑ Spotts, Frederic (1996). Bayreuth: A History of the Wagner Festival. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 169. ISBN 0-300-06665-1.

- ↑ Hamann, Brigitte (2005). Winifred Wagner: A Life At The Heart of Hitler's Bayreuth. Orlando: Harcourt Books. p. 314.

- ↑ Hamann, Brigitte (2005). Winifred Wagner: A Life At The Heart of Hitler's Bayreuth. Orlando: Harcourt Books. p. 354.

- ↑ Hamann, Brigitte (2005). Winifred Wagner: A Life At The Heart of Hitler's Bayreuth. Orlando: Harcourt Books. p. 354.

- ↑ Hamann, Brigitte (2005). Winifred Wagner: A Life At The Heart of Hitler's Bayreuth. Orlando: Harcourt Books. p. 314.

- ↑ Wagner, Wolfgang (1994). "4: Growing Up". Acts: The Autobiography of Wolfgang Wagner. Translated by John Brownjohn. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 43. ISBN 0-297-81349-8.

- ↑ Hamann, Brigitte (2005). Winifred Wagner: A Life At The Heart of Hitler's Bayreuth. Orlando: Harcourt Books. p. 419.

- ↑ Hamann, Brigitte (2005). Winifred Wagner: A Life At The Heart of Hitler's Bayreuth. Orlando: Harcourt Books. p. 432.

- ↑ Hamann, Brigitte (2005). Winifred Wagner: A Life At The Heart of Hitler's Bayreuth. Orlando: Harcourt Books. p. 433.

- ↑ Hamann, Brigitte (2005). Winifred Wagner: A Life At The Heart of Hitler's Bayreuth. Orlando: Harcourt Books. p. 447.

- ↑ Hamann, Brigitte (2005). Winifred Wagner: A Life At The Heart of Hitler's Bayreuth. Orlando: Harcourt Books. p. 430.

- ↑ Hamann, Brigitte (2005). Winifred Wagner: A Life At The Heart of Hitler's Bayreuth. Orlando: Harcourt Books. p. 493.

- ↑ Hamann, Brigitte (2005). Winifred Wagner: A Life At The Heart of Hitler's Bayreuth. Orlando: Harcourt Books. pp. 456–7.

- ↑ Hamann, Brigitte (2005). Winifred Wagner: A Life At The Heart of Hitler's Bayreuth. Orlando: Harcourt Books. p. 390.

- ↑ "Emil Preetorius". Find A Grave. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ↑ Hamann, Brigitte (2005). Winifred Wagner: A Life At The Heart of Hitler's Bayreuth. Orlando: Harcourt Books. p. 136.

- ↑ Spotts, Frederic (1996). Bayreuth: A History of the Wagner Festival. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 67.

- ↑ Spotts, Frederic (1996). Bayreuth: A History of the Wagner Festival. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 180.

- ↑ Schwarzkopf, Elisabeth (1982). On and Off The Record. London: Faber and Faber. p. 21. ISBN 0-571-11928 X.

- ↑ Schwarzkopf, Elisabeth (1982). On and Off The Record. London: Faber and Faber. p. 23. ISBN 0-571-11928 X.

- ↑ Schwarzkopf, Elisabeth (1982). On and Off The Record. London: Faber and Faber. p. 21. ISBN 0-571-11928 X.

- ↑ quoted from 'Under the Swastika' in Modern Music, November–December 1933, in Spotts, Frederic (1996). Bayreuth: A History of the Wagner Festival. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 180n.30.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ quoted from the Sunday Times, 6 August 1933, in Spotts, Frederic (1996). Bayreuth: A History of the Wagner Festival. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 181n.31.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ quoted from Berliner Tageblatt, 24–27 July 1933, in Spotts, Frederic (1996). Bayreuth: A History of the Wagner Festival. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 181n.32.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Spotts, Frederic (1996). Bayreuth: A History of the Wagner Festival. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 181.

- ↑ quoted from 'Under the Swastika' in Modern Music, November–December 1933, in Spotts, Frederic (1996). Bayreuth: A History of the Wagner Festival. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 181–2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Potter, P. M. (2012). "Wagner and the Third Reich: Myths and Realities."". In B. Millington (ed.). Richard Wagner: The Sorcerer of Bayreuth. London: Thames & Hudson.

- ↑ Hamann, Brigitte (2005). Winifred Wagner: A Life At The Heart of Hitler's Bayreuth. Orlando: Harcourt Books. p. 191.

- ↑ "The Preetorius Collection 1960". Preetorius Foundation. The Preetorius Foundation. 9 December 2015. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ↑ "The Preetorius Collection 1960". Preetorius Foundation. The Preetorius Foundation. 9 December 2015. Retrieved 20 February 2020.