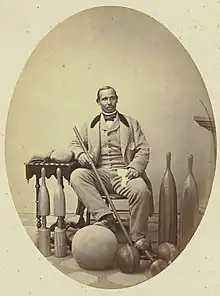

Emanuel D. Molyneaux Hewlett | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | November 15, 1850 Brooklyn, New York |

| Died | September 19, 1929 (aged 78) Washington, DC |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Boston University School of Law |

| Occupation(s) | Attorney, Judge, Activist |

| Years active | 1877–1929 |

| Known for | One of the first African-American attorneys admitted to the United States Supreme Court bar; first African-American Justice of the Peace in Washington, DC |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives | Virginia Hewlett Douglass (sister) |

Emanuel D. Molyneaux Hewlett (November 15, 1850 – September 19, 1929)[1] was an American attorney, judge, and civil rights activist. He was among the first African Americans to be admitted to the bar of the United States Supreme Court, in 1883, and among the first to argue cases before the Supreme Court. He served as a Justice of the Peace in Washington, DC, from 1890 to 1906.

Early life

Family background

Hewlett was born in Brooklyn, New York, on November 15, 1850, the son of Aaron Molyneaux Hewlett (c. 1821-December 6, 1871) and Virginia Josephine Molyneaux Hewlett (née Lewis, c. 1821–1882). He had two sisters, Virginia Lind and Aaronella, and two brothers, Aaron and Paul, a Shakespearean actor who performed under the name "Paul Molyneaux."[2][3]

Aaron and Virginia Hewlett were part of the nineteenth-century physical culture movement. In 1854 Aaron Hewlett, who had previously worked as a barber and a porter, opened a sparring school called Molineaux House in Brooklyn. The following year the family moved to Worcester, Massachusetts, where he opened a popular gymnasium. This move led to his being hired in 1859 as the first director of Harvard College's new gymnasium, where he worked for fourteen years, serving as an instructor in gymnastics, baseball, rowing, and boxing, coaching sports teams, and managing the gym's equipment.[4][5][6] Virginia Hewlett was a gymnastics instructor who held courses for women.[7] They ran a gymnasium in Cambridge together in addition to Aaron's work at Harvard.[6]

Aaron Hewlett was active in the fight for civil rights for African Americans in Massachusetts, challenging illegal discrimination in public places and supporting alternatives to discriminatory institutions. In April 1866, after he and one of his daughters were forced by the staff of the Boston Theater to sit in the balcony even though they had purchased tickets for seats in the parquet, he petitioned for changes to Massachusetts' anti-discrimination law, on the grounds that the current law clearly wasn't working.[8] Two years later he was part of a group of twenty people who petitioned to have the license of a Cambridge skating rink revoked on grounds of unlawful discrimination. Also in 1868, he was part of a group that incorporated the Cambridge Land and Building Association, an organization formed to provide loans for African Americans who could not get service from white-run banks.[9]

Education

Hewlett attended Cambridge public schools and graduated from Cambridge High School.[10] He then studied at Boston University School of Law, becoming its first black graduate in 1877.[11]

Legal career

Hewlett practiced law in Boston from 1877 to 1880, then moved to Washington, DC.[10] In 1883 he was admitted to the bar of the United States Court of Claims and the United States Supreme Court bar.[10]

In 1890 Hewlett was appointed a justice of the peace for the District of Columbia by President Benjamin Harrison. He was reappointed by presidents Cleveland, McKinley, and Theodore Roosevelt for a total of sixteen years of service.[12] Justices of the peace presided over a "poor man's court," with jurisdiction limited to civil cases involving less than $300.00.[13][14] Nevertheless, this was considered a prestigious appointment for a black attorney. In 1906, when the number of justices of the peace was reduced from ten to six, Hewlett was not reappointed by President Roosevelt. Some in the African American press argued that this was a political decision at the highest level, involving lobbying by national black leader Booker T. Washington in favor of Washington's other black justice of the peace, Robert Terrell.[15]

Supreme Court activities

As a member of the Supreme Court bar, Hewlett was involved in ten cases as counsel or co-counsel, often joining appeals filed on behalf of black southern defendants.[16][17] He recommended at least two other African American attorneys for admission to the bar, Noah W. Parden of Tennessee in 1906 and Shelby J. Davidson of Kentucky in 1912.[18]

Many of the cases with which Hewlett was associated were attempts to win a broad interpretation of the Reconstruction amendments to the Constitution by the Supreme Court by arguing that the civil rights of black defendants, especially the right to equal protection under the law, had been violated through the wilful exclusion of African Americans from juries and grand juries. In Charley Smith v. State of Mississippi 162 U.S. 592 (1896) and John G. Gibson v. State of Mississippi 162 U.S. 565 (1896), Hewlett worked with attorney Cornelius J. Jones to argue that convicted murderers Smith and Gibson had been denied juries of their peers because the juries were empaneled using voter rolls that excluded black citizens. Both cases were dismissed by the court for reasons of lack of jurisdiction; legal scholar R. Volney Riser notes that this may have stemmed from Jones' failure to provide sufficient evidence to interpret the motivations of the Mississippi courts.[19][20] In Brownfield v. North Carolina 189 U.S. 426 (1903), Hewlett worked with attorneys J.L. Mitchell and W.J. Whipper in a case that made similar arguments, again seeking to overturn a murder conviction on the grounds that black jurors had been excluded due to their race or color. In this case, the court concluded that Hewlett and his colleagues had failed to prove that blacks were purposefully excluded from juries by the administration of the law.[21]

In Carter v. Texas 177 U.S. 442 (1900), in which Hewlett served as co-counsel alongside attorney Wilford H. Smith, this tactic was somewhat successful. Smith argued that Seth Carter's indictment for murder should be quashed because no blacks had been chosen to sit on the grand jury that presented it, despite blacks being one-fourth of Galveston, Texas voters. This has been interpreted as a victory for the idea that black defendants were entitled to a jury that included their black peers, making Smith the first African American attorney to successfully argue a case before the Supreme Court; however, the court's decision was narrowly focused on procedure, specifically the fact that Carter had never been given a chance to object to the composition of the grand jury (which had been empaneled before charges were filed against him), in violation of Texas law.[22][23]

In the Ed Johnson case, in which Hewlett acted as co-counsel to Noah Parden, Parden made an argument on equal protection grounds that the trial of Ed Johnson, who faced the death penalty after a conviction for rape, had violated Johnson's Constitutional rights, including through the exclusion of blacks from the jury. Parden succeeded in convincing Justice John Marshall Harlan to stay Johnson's execution until the case could be argued before the full court, but it was never heard because Johnson was taken from the jail in Chattanooga, Tennessee, and lynched.[24] Hewlett did not participate in United States v. Shipp 203 U.S. 563 (1906), the case that resulted from this abrogation of federal authority.[25]

Legal activism

Hewlett also fought against other manifestations of racism and discrimination in his work as an attorney. He filed a number of cases challenging denials of access to public accommodations on his own behalf and for African American clients. In 1884, he sued a steamboat clerk in Washington Police Court after the clerk refused to provide him with the meal to which he was entitled by his ticket. The case was dismissed, with the judge explaining that Hewlett was technically correct, but the government had not "maintained the issue" of enforcing equal access.[26][27] In 1889, Hewlett represented George L. Pryor, a black lawyer from Norfolk, Virginia, in a suit against the doorman at Harris' Bijou Theater in Washington who had seated Pryor and a companion at the back of the theater instead of in the seats they had purchased,[28] and in 1900 he was co-counsel in W.T. Ferguson's case against the management of the Grand Opera House.[29]

Along with other black Washingtonians, Hewlett used the courts to fight against bars and restaurants that were violating the Equal Services Acts of 1872 and 1873, local DC laws that barred racial discrimination in bars and restaurants, by refusing to serve black customers or trying to drive them away through tactics like ignoring them or overcharging them.[30][31] In 1887, he filed a complaint against the popular restaurant Harvey's Oyster House for denying him service. Harvey's was fined $100 but appealed, and eventually the case was dropped.[16] He also pushed back against denial of service in 1907 by alerting the federal marshall in charge of the District of Columbia city hall that a lunchroom in the building had refused to serve him and a black colleague. Although the marshall, who had given the lunchroom operator free use of the space, informed her that discrimination was illegal, she responded by closing the restaurant on the grounds that her white patrons would not share a facility with blacks.[32]

Another issue with which Hewlett was engaged was interracial marriage. In 1890 he served as counsel in the cases of Tutty v. State of Georgia and Ward v. State of Georgia, which stemmed from the marriage of Charles Tutty, a white man, and Rosa Ward Tutty, a black woman. They were married in Washington, DC, but when they returned to their home in Georgia, where interracial marriage was illegal, they were arrested and convicted of fornication. On appeal, the question was whether they were committing fornication because they could not legally marry (the prosecution's argument), or incapable of doing so because they were married (the argument of Hewlett and his co-counsel Judge Parker Jordan). In both cases, the guilty verdict was upheld.[33][34] Hewlett also addressed this issue in his role as justice of the peace. In 1902, he officiated at the wedding of Julia Johnson and George Wilson from Baltimore, who came to Washington and were married in his court because their home state of Maryland prohibited interracial marriage.[35]

In 1915, Hewlett was involved with a class-action reparations case filed by Cornelius J. Jones on behalf of a group of former slaves, asserting ownership of $68 million paid in taxes on cotton produced using slave labor between 1859 and 1868. Jones and the case became the target of harassment from the United States Treasury Department and the Post Office in the fall of 1915. In November, Hewlett publicly declared that he "sees no merit in the suit" and was withdrawing from the case.[36][37]

Civic activities and activism

In addition to his work as a lawyer and judge, Hewlett was part of a series of real estate and insurance businesses, including the Alpha Law, Real Estate and Collection Company (1892),[38] the Douglass Life Insurance Company (1901)[39] and Hewett, Horner, Watts & Co., a real estate firm (1906).[40] Such firms provided a public service to the black community. White-run companies were often unwilling to conduct real estate transactions or sell insurance to black customers, who they believed were inherently bad risks, so these ventures provided a needed alternative.[41]

He belonged to civil rights groups that emerged at the turn of the twentieth century to support the enforcement of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments and to fight against discrimination, segregation and the Jim Crow legal system, and lynching. He often served as legal counsel. In 1898, he was a founding member of the National Racial Protective Association[42] and the Afro-American Council.[43] During the 1910s and 1920s he was actively involved in the National Equal Rights League,[44] and during World War I he participated in protests in Washington, DC against mistreatment of African American soldiers.[45]

Personal life

Hewlett remained a bachelor until late in life and had no children. By 1900 he was living as a boarder in the home of Elizabeth P. Brooks, a widow;[46] Hewlett and Brooks were married on August 14, 1920.[47] In 1890, after the death of his sister Virginia Hewlett Douglass (whose father-in-law was Frederick Douglass), he became custodian of Virginia and Frederick Douglass Jr's two minor children, Charles Paul Douglass and Robert Smalls Douglass.[48]

Elizabeth Hewlett died in July 1926, aged 77.[49] Emanuel Hewlett died on September 19, 1929, and was interred at Columbian Harmony Cemetery in Washington, DC.[50]

References

- ↑ "Judge E.M. Hewlett is Dead at Home". Evening Star (Washington, DC). September 21, 1929.

- ↑ Aaron M. Hewlett (case no. 5155). Middlesex County (Mass.) Probate Packets (1-4720), second series, 1872-1967 (and 4703-19,935). Accessed via Ancestry.com Massachusetts, Wills and Probate Records, 1635-1991 database.

- ↑ "People of Color in Shakespearean Roles". University of Maryland Libraries. May 3, 2016. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- ↑ Bergeson-Lockwood, Millington William (2011). Not as Supplicants, but as Citizens: Race, Party and African-American Politics in Boston, Massachusetts, 1864-1903. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Michigan. p. 190.

- ↑ Gems, Gerald R., Linda J. Borish, and Gertrud Pfister (2017). Sports in American History from Colonization to Globalization (2 ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. p. 111.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 Moore, Louis (Fall 2011). "Fit for Citizenship: Black Sparring Masters, Gymnasium Owners, and the White Body, 1825-1886". Journal of African American History. 96 (4): 448–473. doi:10.5323/jafriamerhist.96.4.0448. S2CID 141782656.

- ↑ "General Information about Aaron Molyneaux Hewlett and Madam Molyneaux Hewlett, 1861-". HOLLIS, Harvard Library. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- ↑ Bergeson-Lockwood. Not as Supplicants. pp. 190–191.

- ↑ "Freedom's Agenda: African American Petitions to the Massachusetts Government 1600-1900". Commonwealth Museum of Massachusetts. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- 1 2 3 "Two Colored Justices". Cambridge Chronicle [via Cambridge Public Library]. November 23, 1901. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- ↑ "Advancing Justice from Day One". The Record: 16. Spring 2018.

- ↑ Riser, R. Volney (2010). Defying Disenfranchisement: Black Voting Rights Activism in the Jim Crow South, 1890-1908. Baton Rouge, LA: LSU Press. p. 43.

- ↑ Ferris, William H. (1913). The African Abroad, or, His Evolution in Western Civilization, vol. 2. New Haven, CT: Tuttle, Morehouse & Taylor Press. p. 858.

- ↑ Higganbotham, A. Leon Jr. (1992–1993). "Seeking Pluralism in Judicial Systems: The American Experience and the South African Challenge". Duke Law Journal. 42: 1035 ftnt.

- ↑ "President Roosevelt and Booker T. Washington". The Broad Ax (Chicago) (via LOC Chronicling America). January 6, 1906. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- 1 2 Kelly, John (February 13, 2018). "DC Law said African Americans Could Eat Anywhere. The Reality was Different". Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- ↑ Riser. Defying Disenfranchisement. p. 43.

- ↑ "[no headline]". The Broad Ax (Chicago) (via LOC Chronicling America). November 23, 1912. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- ↑ Riser. Defying Disenfranchisement. pp. 43–44.

- ↑ Brown, Amanda (April 14, 2018). "Gibson v. Mississippi". Mississippi Encyclopedia.

- ↑ "Brownfield v. South Carolina". FindLaw. March 9, 1903.

- ↑ "Carter v. State of Texas". FindLaw. April 16, 1900.

- ↑ Riser. Defying Disenfranchisement. p. 103.

- ↑ Curriden, Mark, and Leroy Phillips Jr. (1999). Contempt of Court: The Turn-of-the-Century Lynching that Launched One Hundred Years of Federalism. New York: Faber and Faber. pp. 188–193. ISBN 978-0-571-19952-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "US v. Shipp (1909)". FindLaw. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- ↑ "The Color Line". Boston Globe (via Newspapers.com). October 2, 1884.

- ↑ "A Civil Rights Case Disposed Of". Galveston Daily News. October 9, 1884.

- ↑ "Another Color Line Case". Evening Star (Washington, DC) (via LOC Chronicling America). May 10, 1889.

- ↑ "[no headline]". The Colored American (Washington, DC) (via LOC Chronicling America). February 24, 1900.

- ↑ Kelly, John (February 11, 2018). "Remembering the 'Lost Laws' of Washington". Washington Post.

- ↑ Kelly, John (February 12, 2018). "In 1872, Black Washingtonians Started Testing a New Anti-Discrimination Law". Washington Post.

- ↑ "Deprived of Lunch Room". Evening Star (Washington, DC) (via LOC Chronicling America). April 3, 1907.

- ↑ "An Interesting Case". Richmond Planet (via Virginia Chronicle). November 29, 1890.

- ↑ "Tutty v. State". The Southeastern Reporter. 13: 711. 1891–1892.

- ↑ "White Man's Negro Bride". Richmond Dispatch (via Virginia Chronicle). August 28, 1902.

- ↑ "M'Adoo Issues Timely Warning". Denver Star (via LOC Chronicling America). November 13, 1915.

- ↑ Berry, Mary Frances (March 2018). "Taking the United States to Court: Callie House and the 1915 Cotton Tax Reparations Litigation". Journal of African American History. 103 (1–2): 97–100. doi:10.1086/696360. S2CID 150198613.

- ↑ "[no headline]". Washington Bee (via LOC Chronicling America). June 4, 1892.

- ↑ Hilyer, Andrew F. (1901). The Twentieth Century Union League Directory. Washington, DC: Union League of the District of Columbia. p. 58.

- ↑ "New Real Estate Company". Evening Star (Washington, DC) (via LOC Chronicling America). October 13, 1906.

- ↑ Woodson, Carter G. (April 1929). "Insurance Business among Negroes". Journal of Negro History. 14 (2): 202–226. doi:10.2307/2714068. JSTOR 2714068. S2CID 149560502.

- ↑ "Racial Troubles". Washington Bee (via LOC Chronicling America). December 24, 1898.

- ↑ Alexander, Shawn Leigh (2006). "The Afro-American Council and its Challenge of Louisiana's Grandfather Clause". In Green, Chris, Rachel Rubin, and James Smethurst (ed.). Radicalism in the South Since Reconstruction. New York: PalgraveMacMillan. pp. 13–38.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ↑ "Senator Henry Cabot Lodge Saves the Dyer Bill by his Insistence on Report". Richmond Planet (via Virginia Chronicle). June 10, 1922.

- ↑ Gregory, Thomas Montgomery (June 20, 1919). Report: Negro Situation in Northeast Africa and the Activities of Lawyer Emanuel W. Hewlett. War Department Military Intelligence, Correspondence. 5. http://dh.howard.edu/tmg_intellicorres/5

- ↑ "Emanuel M. Herolett [Hewlett] in the 1900 United States Federal Census". Ancestry.com.

- ↑ "Emanuel M. Hewlett in the District of Columbia, Compiled Marriage Index, 1830-1921". Ancestry.com.

- ↑ Blight, David W. (2018). Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom. New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 678.

- ↑ "Mrs. E.M. Hewlett Dies". Evening Star (Washington, DC) (via LOC Chronicling America). July 20, 1896.

- ↑ "[no headline]". Evening Star (Washington, DC) (via LOC Chronicling America). September 22, 1929.