.jpg.webp)

Eingreif division (German: Eingreifdivision) is a term for a type of German Army formation of the First World War , which developed in 1917, to conduct immediate counter-attacks (Gegenstöße) against enemy troops who broke into a defensive position being held by a front-holding division (Stellungsdivision) or to conduct a methodical counter-attack (Gegenangriff) 24–48 hours later. Attacks by the French and British armies against the Westheer on the Western Front had been met in 1915 and 1916 by increasing the number and sophistication of trench networks, the original improvised defences of 1914 giving way to a centrally-planned system of trenches in a trench-position and then increasing numbers of trench-positions, to absorb the growing firepower and offensive sophistication of the Entente armies.

During the Battle of the Somme (1 July – 18 November 1916), the use of defensive lines began to evolve into the defence of the areas between them, using the local troops of the trench holding divisions and Ablösungsdivisionen (relief divisions), held back beyond the range of Franco-British artillery, to replace front line divisions as they became exhausted. In the winter of 1916–1917, the use of such divisions and the fortified zones between trench lines was codified and divisions trained in the new defensive tactics. Training was based on the experience of the defensive battles of 1916 and the new principles of fortification, to provide the infrastructure for the new system of defensive battle by Stellungsdivisionen and Eingreifdivisionen (counter-attack divisions).

The new defensive principles and fortifications were used in 1917 to resist the Franco-British offensives. After failures at Verdun in December 1916 and at Arras in April 1917, the system of fortifications defended by Stellungsdivisionen supported by Eingreif divisions counter-attacking from the rear was vindicated during the French attacks of the Nivelle Offensive. The continuation of British attacks at Arras in the wake of the French debacle on the Aisne, led to the highest rate of casualties per day of the war but the system failed again at the Battle of Messines. German defensive tactics reached their ultimate refinement during the Third Battle of Ypres and there were only slight alterations during the defensive battles of late 1918. In the interwar period, German defensive thinking incorporated the new technology of aircraft, tanks, anti-aircraft guns and anti-tank guns in a much deeper defensive system filled with positions for delaying actions, before a counter-attack was made by armoured and mechanised formations.

German defensive tactics

1914–1916

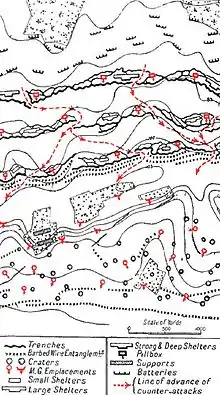

German defensive tactics had been based on the publication Exerzier-Reglement für die Infanterie of 1906 (Drill Regulations for the Infantry), which expected defensive warfare to be short periods between offensives. On the Somme front, the construction plan ordered by Falkenhayn in January 1915 had been completed. Barbed wire obstacles had been enlarged from one belt 5–10 yd (4.6–9.1 m) wide to two, 30 yd (27 m) wide and about 15 yd (14 m) apart. Double and triple thickness wire was used and laid 3–5 ft (0.91–1.52 m) high. The front line had been increased from one line to three, 150–200 yd (140–180 m) apart, the first trench (Kampfgraben, battle trench) occupied by sentry groups, the second (Wohngraben, living trench) for the front-trench garrison and the third trench for local reserves. The trenches were traversed and had sentry-posts in concrete recesses built into the parapet. Dugouts had been deepened from 6–9 ft (1.8–2.7 m) to 20–30 ft (6.1–9.1 m), 50 yd (46 m) apart and large enough for 25 men. [1]

An intermediate line of strong points (Stützpunktlinie) about 1,000 yd (910 m) behind the front line had also been built. Communication trenches ran back to the reserve line, renamed the second line, which was as well-built and wired as the first line. The second line was built beyond the range of Allied field artillery, to force an attacker to stop and move field artillery forward before assaulting the line. After the Herbstschlacht (Autumn Battle) in Champagne during late 1915, a third line another 3,000 yd (1.7 mi; 2.7 km) back from the Stützpunktlinie was begun in February 1916 and was nearly complete when the Battle of the Somme began.[1] German artillery was organised in a series of Sperrfeuerstreifen (barrage sectors). The Somme defences were crowded towards the front trench, with a regiment having two battalions near the front trench system and the reserve battalion divided between the Stützpunktlinie and the second line, all within 2,000 yd (1,800 m) of the front line.[2]

Tactical revision, 1917

Winter 1916–1917

New manuals

After the Battle of the Somme (1 July – 18 November), General Erich Ludendorff had German defensive doctrine revised.[3] On 1 December, the Oberste Heeresleitung (OHL, supreme army command) published new tactical instructions, Grundsätze für die Führung in der Abwehrschlacht im Stellungskrieg (Principles of Command for Defensive Battle in Positional Warfare), in which the policy of unyielding defence of ground regardless of its tactical value, was replaced.[4][lower-alpha 1] Positions suitable for artillery observation and communication with the rear were to be defended, where an attacking force would "fight itself to a standstill and use up its resources while the defenders conserve[d] their strength". Defending infantry would fight in areas, with the front divisions in an outpost zone up to 3,000 yd (1.7 mi; 2.7 km) deep, behind listening posts, with the main line of resistance placed on a reverse slope, in front of artillery observation posts kept far enough back to retain observation over the outpost zone. Behind the main line of resistance was a Grosskampfzone (main battle zone), a second defensive area 1,500–2,500 yd (1,400–2,300 m) deep, also sited as far as possible on ground hidden from enemy observation, while in view of German artillery observers was to be built.[7] A rückwärtige Kampfzone (rear battle zone) further back was to be occupied by the reserve battalion of each regiment.[8]

Somme analysis

Erfahrungen der I Armee in der Sommeschlacht (Experience of the German 1st Army in the Somme Battles), written by Colonel Fritz von Loßberg, Chief of Staff of the 1st Army was published on 30 January 1917. During the Battle of the Somme, Loßberg had been able to establish a line of Ablösungsdivisionen (relief divisions), with the reinforcements from Verdun, which had arrived in greater numbers in September 1916. In his analysis, Loßberg opposed the granting of discretion to front trench garrisons to retire, as he believed that manoeuvre did not allow the garrisons to evade Allied artillery fire, which could blanket the forward area and would invite opposing infantry to occupy vacant areas. Loßberg considered that spontaneous withdrawals would disrupt the counter-attack reserves as they deployed and further deprive battalion and division commanders of the means to conduct an organised defence, which the dispersal of infantry over a wider area had already made difficult. Loßberg and other officers had severe doubts as to the ability of relief divisions to arrive on the battlefield in time to conduct a Gegenstoß aus der Tiefe (immediate counter-attack from the deep) from behind the battle zone. The sceptics wanted the Somme practice of fighting in the front line to be retained and authority devolved no further than the battalion, to maintain control ready for a Gegenangriff (methodical counter-attack) after 24–48 hours, by the relief divisions. Ludendorff added the analysis to the new Grundsätze....[9]

Field fortification

Allgemeines über Stellungsbau (Principles of Field Fortification) was published in January 1917 on which new defensive fortifications were to be based, to provide the infrastructure for the new defensive tactics. By April an outpost zone (Vorpostenfeld) held by sentries, had been built along the Western Front. Sentries could retreat to larger positions (Gruppennester) held by Stoßtrupps (five men and an NCO per Trupp), who would join the sentries to recapture sentry-posts by (Gegenstoß (immediate counter-attack). Defensive procedures in the battle zone were similar but with greater numbers of men. The front trench system was the sentry line for the battle zone garrison, which was allowed to move away from concentrations of enemy fire, then counter-attack to recover the battle and outpost zones. Such withdrawals were envisaged as occurring on small parts of the battlefield, which had been made untenable by Allied artillery fire, as the prelude to Gegenstoß in der Stellung (immediate counter-attack within the position). Such a decentralised battle by large numbers of small infantry detachments would present the attacker with unforeseen obstructions. The further the penetration, the greater would be the density of defenders, equipped with automatic weapons, camouflaged and supported by observed artillery fire. A school was opened in January 1917 to teach infantry commanders the new methods.[10]

Eingreifdivision

Eingreif is generally translated as counter-attack but the term has other connotations.[11] In German military thinking, it included a sense of intervening and is better understood as interlocking or dovetailing, in which the Eingreifdivision came under the command of the Stellungsdivision and joined with the defensive garrison and its fortifications.[11] The term was adopted during the Battle of Arras (9 April – 16 May 1917) to replace Ablösungsdivision (relief division), to end confusion over the purpose of divisions held in readiness. There were also calls for each Stellungsdivision to have the support of an Eingreifdivision but Ludendorff could not find sufficient divisions for this.[12] James Edmonds, the British official historian, called them special reserve or super counter-attack divisions.[13] Such methods required large numbers of reserve divisions ready to counter-attack, which were obtained by creating 22 new divisions, moving some divisions from the eastern front and Operation Alberich (Unternehmen Alberich) in March 1917, which shortened the front. By the spring, the German army in the west (Westheer) had accumulated a strategic reserve of 40 divisions. Over the winter, certain divisions were trained as Eingreifdivisionen but a strict distinction between these divisions and the remaining Stellungsdivisionen could not always be maintained.[14]

The new system reflected the views of Carl von Clausewitz (1 June 1780 – 16 November 1831) that defensive battle should not be passive but one of deflection and attack ("eine Verbindung von Parade und Stoss"), with the Eingreifdivisionen providing a "flashing sword of retaliation" ("das blitzende Vergeltungsschwert").[15] On 1 January 1917, General Otto von Moser was appointed to lead a new Divisionskommandeur Schule at Solesmes near the Belgian border, to teach the new defensive thinking, using a training ground and a Testing and Instructional Division at full establishment for demonstrations. The first course from 8 to 16 February was attended by about 100 officers of the Westheer who attended morning lectures and afternoon exercises and a second course run from 20 to 28 February included guest officers from the Eastern Front and three Austro-Hungarian army observers. The third course from 4 to 12 March included officers from other armies of the Central Powers and then Moser was transferred to take command of the XIV Reserve Corps. Many of the students accepted the new defensive thinking but Loßberg and other dissenters objected to discretion to retreat being given to the front garrison. A second school was set up at Sedan for the officers of Heeresgruppe Deutscher Kronprinz.[16][17] During the British preparatory bombardment of Messines Ridge before the attack on 7 June, the 24th Division was relieved by the 35th Division and the 40th Division by the 3rd Bavarian Division, the local Eingreifdivisionen and these were replaced by the 7th Division and the 1st Guard Reserve Division, unfamiliar with the area and not trained Eingreifdivisionen.[18] Some were retained as they were rebuilt after spending time in the line; the 24th Division was given six weeks' rest and reconstituted as the Eingreifdivision of Group Aubers before returning to Flanders on 11 August. The 23rd Reserve Division acted as a Stellungsdivision from 23 June to 29 July, spent August recuperating and September as an Eingreifdivision for Gruppe (Group) Dixmude, before being rushed to Group Ypres on 20 September to relieve the 2nd Guard Division.[19]

Training

When the 183rd Division arrived in Flanders became an Eingreifdivisionen for Gruppe Ypren. The divisional artillery had been reorganised, with the medium and heavy guns participating in conventional artillery bombardments and the three battalions of Field Artillery Regiment 183 being divided between the three infantry regiments. Each infantry regiment received two assault batteries and a platoon of Reserve Engineer Battalion 16, to provide observed and direct fire. Training in the new role led to infantry companies being reorganised and new specialisms being introduced. The three platoons in each company became a rifle section, an assault group, a grenade-launcher troop and a light machine-gun section. The use of hand grenades became more important and coloured flares were used as the quickest way to signal to the rear.[20]

Defensive tactics

The German army distinguished between a hasty counter-attack (Gegenstoß in der Stellung immediate counter-attack from within the position) to prevent an opponent from consolidating captured positions and a methodical counter-attack (Gegenangriff), which took place after a period for reconnaissance, reinforcement and preliminary artillery fire.[21] The new tactics required commanders to act on their initiative and troops to perform complicated manoeuvres in battle, which could only be implemented through a comprehensive training programme to make it possible.[22] Eingreif divisions were to wait in readiness at the rear of the defensive zone to join the more immediate Gegenstoß engagements, if troops held in reserve by the Stellungsdivision were insufficient to restore the position.[23] With the increasing Allied superiority in munitions and manpower, attackers might still penetrate to the second (artillery protection) line, leaving German garrisons isolated in Widerstandsnester (Widas, resistance nests), still inflicting losses and disorganisation on the attackers. As the attackers tried to capture the Widas and dig in near the German second line, Sturmbattalions and Sturmregimenter of the Eingreif divisions would advance from the rückwärtige Kampfzone into the battle zone, in an immediate counter-attack (Gegenstoß aus der Tiefe, immediate counter-attack from the deep). When immediate counter-attacks failed, the Eingreif divisions would take 24–48 hours to prepare a Gegenangriff (methodical counter-attack), provided that the lost ground was essential for the retention of the main position.[14]

Third Battle of Ypres

31 July

The British advance in the centre of the front had caused serious concern to the German commanders.[24] Penetration of the defensive system was expected but the 4,000 yd (2.3 mi; 3.7 km) advance in the centre of the attack had not been anticipated. At noon, the British advance on the Gheluvelt Plateau to the south had been stopped by the local German defenders and their artillery. In the centre, regiments of the 221st and 50th Reserve Divisions, the Eingreif divisions at the rear of the Group Ypres defensive zone, advanced over the Broodseinde–Passchendaele ridge, unseen by British reconnaissance aircraft.[25] The Eingreif regiments began their advance from 11:00 to 11:30 a.m. and the German artillery began a creeping barrage at 2:00 p.m. along the centre of the British front. The Eingreif regiments drove back the three most advanced British brigades, inflicting 70 per cent casualties, recaptured the Zonnebeke–Langemarck road and St Julien, before the advance was stopped on the black line (second objective) by mud, the British artillery and machine-gun fire.[26][27][28] The Eingreif divisions had little success on the northern flank of the Anglo-French attack, where the attackers had time to dig in. After losing many men to British artillery-fire while advancing around Langemarck, the Germans managed to push back a small British bridgehead on the east bank of the Steenbeek; the French repulsed the Germans around St Janshoek and followed up to capture Bixschoote.[29] Counter-attacks in the afternoon by the Stellungsdivisionen on the southern flank, intended to recapture Westhoek Ridge, were able to advance a short distance from Glencorse Wood before British artillery-fire and a counter-attack pushed them back again.[30][lower-alpha 2]

22 September

The leading regiment of an Eingreif division was to advance into the zone of the front division, with its other two regiments moving forward in close support. The support and reserve assembly areas in the Flandern Stellung were termed Fredericus Rex Raum and Triarier Raum, analogies with the structure of a Roman legion. Eingreif divisions were accommodated 10,000–12,000 yd (5.7–6.8 mi; 9.1–11.0 km) behind the front line and began their advance to their assembly areas in the rear zone (rückwärtige Kampffeld), ready to intervene in the main battle zone (Grosskampffeld).[31] After the defeat of Menin Road Ridge, the German defensive deployment was changed. In August, German Stellungsdivisionen had two regiments of three battalions each in the front position, with the third regiment in reserve. The front battalions had needed to be relieved much more frequently than expected due to constant British bombardments and the weather; units had become mixed up. Reserve regiments had not been able to intervene quickly, leaving front battalions unsupported until Eingreif divisions arrived, some hours after the commencement of the attack. The deployment was changed to increase the number of troops in the front zone.[32]

By 26 September all three regiments of the front-line division were forward, each holding an area 1,000 yd (910 m) wide and 3,000 yd (1.7 mi; 2.7 km) deep; one battalion was placed in the front-line, the second in support and the third in close reserve.[32] The battalions were to move forward successively, to engage fresh enemy battalions, which had leap-frogged through those that had delivered the first attack. The Eingreif divisions were to deliver an organised attack with artillery support later in the day, before the British could consolidate their new line.[33] The change was intended to remedy the neutralisation of the front division reserves, which had been achieved by the British artillery on 20 September, so that they could intervene before the Eingreif divisions arrived. On 22 September, new tactical requirements were laid down: more artillery counter-bombardment was to be used between British attacks, half against British artillery and half against infantry, increased raiding was ordered to induce the British to hold their positions in greater strength, giving German artillery a denser target; better artillery observation was demanded in the battle zone, to increase the accuracy of German artillery fire when British troops advanced into it and quicker counter-attacks were to be made.[34]

30 September

Following the costly defeats of Menin Road on 20 September and Polygon Wood on 26 September, the German commanders made more changes to the defensive organisation and altered their counter-attack tactics, which had been negated by the British combination of limited attack and much greater artillery firepower than August. Eingreif divisions had engaged in "an advance to contact during mobile operations" in August, which had achieved several costly defensive successes.[35] German counter-attacks in September had been "assaults on reinforced field positions", due to the short British infantry advances and emphasis on defeating Gegenstoße (immediate counter-attacks) in the position or from the deep. The period of dry weather and clear skies which began in early September, had greatly increased the effectiveness of British air observation and artillery fire. German counter-attacks were defeated with heavy casualties, after arriving too late to take advantage of disorganisation. The British changes meant that a defence in depth had been swiftly established on reverse slopes, behind standing barrages, in dry, clear weather, with specialist air reconnaissance for observation of German troop movements and improved contact patrolling and ground-attack operations by the RFC. German artillery which was able to fire, despite British counter-battery shelling, became unsystematic due to uncertainty over the whereabouts of German infantry and British infantry benefited from the opposite.[36] On 28 September Albrecht von Thaer, Staff Officer at Gruppe Wijtschate wrote that the experience was "awful" and that he did not know what to do.[37]

Ludendorff later wrote that he had regularly discussed the situation with General Hermann von Kuhl and Loßberg, to try to find a remedy for the overwhelming British attacks.[38] Ludendorff ordered a strengthening of the forward garrisons by the ground holding divisions and all machine-guns, including those of the support and reserve battalions of the front line regiments, were sent into the forward zone, to form a cordon of four to eight guns every 250 yd (230 m).[39] The Stoß regiment of each Eingreif division, was placed behind each front division in the artillery protective line behind the forward battle zone, which increased the ratio of Eingreif divisions to Stellungsdivisionen to 1:1. The Stoß regiment was to be available to launch counter-attacks while the British were consolidating; the remainder of each Eingreif division was to be withheld for a Gegenangriff (methodical counter-attack) a day or two later.[40] Between British attacks, the Eingreif divisions were to make more spoiling attacks.[41]

A 4th Army operation order on 30 September pointed out that the German position in Flanders was restricted by the local topography, the proximity of the coast and the Dutch frontier, which made local withdrawals impossible. The instructions of 22 September were to be followed, with more bombardment by field artillery, using at least half of the heavy artillery ammunition, for observed fire on infantry positions in captured pillboxes, command posts, machine-gun nests, on duck board tracks and field railways. Gas bombardment was to be increased, on forward positions and artillery emplacements, when the wind allowed. Every effort was to be made to induce the British to reinforce their forward positions, where the German artillery could engage them, by making spoiling attacks to recapture pillboxes, improve defensive positions and harass the British infantry, with patrols and diversionary bombardments.[42] From 26 September to 3 October, the Germans attacked and counter-attacked at least 24 times.[43] British intelligence predicted the German changes in an intelligence summary of 1 October, foreseeing the big German counter-attack planned for 4 October.[44][45]

7–13 October

On 7 October, the 4th Army abandoned the reinforcement of the front defence zone, after the "black day" of 4 October. Front line regiments were dispersed again, with reserve battalions moved back behind the artillery protective line and Eingreif divisions organised to intervene as swiftly as possible, despite the risk of being devastated by the British artillery. Counter-battery fire against British artillery was to be increased to protect the Eingreif divisions as they advanced. Ludendorff insisted on an advanced zone, (Vorfeld) 500–1,000 yd (460–910 m) deep, to be occupied by a thin line of sentries with a few machine-guns. The sentries were to retire on the main line of resistance (Hauptwiederstandslinie) at the back of this advanced zone when attacked, while the artillery was quickly to barrage the area in front of it. Support and reserve battalions of the front-line and Eingreif divisions, would gain time to move up to the main line of resistance, where the battle would be fought, if artillery-fire had not stopped the British infantry advance.[46]

An Eingreif division was to be placed behind each front-line division, with instructions to ensure that it reached the British before they could consolidate. If a swift counter-attack was not possible, there was to be a delay to organise a methodical counter-attack, after ample artillery preparation. Armin ordered on 11 October that the Stellungs- and Eingreif- divisions of groups Staden, Ypres and part of Gruppe Wijtschate were to take turns in the front line, Eingreif becoming more of a role than an identity.[46] The revised defensive scheme was promulgated on 13 October, over Rupprecht's objections.[47] Artillery-fire was to replace the machine-gun defence of the forward zone as far as possible, which Rupprecht believed would allow the British artillery too much freedom to operate. The thin line of sentries of one or two Gruppen (thirteen men and a light machine-gun each) in company sectors proved inadequate, as the British were easily able to attack them and lift prisoners.[48] At the end of October, the sentry line was replaced by a conventional outpost system of double Gruppen.[49]

The German defensive system had become based on two divisions, holding a front 2,500 yd (1.4 mi; 2.3 km) wide and 8,000 yd (4.5 mi; 7.3 km) deep, half the area that two divisions previously were expected to hold.[49] The necessity of such reinforcement was caused by the weather, devastating British artillery-fire and the decline in the numbers and quality of German infantry. Concealment (die Leere des Gefechtsfeldes) was emphasised, to protect the divisions from British fire power, by avoiding anything resembling a trench system, in favour of dispersal in crater fields. Such a method was only made feasible by the rapid rotation of units; battalions of the front-divisions were relieved after two days and divisions every six days. On 23 October, the Stellungsdivision commander was given command of the Eingreifdivision, creating a new two-division tactical unit. The quicker rotation of divisions led to the distinction between Eingreif divisions and Stellungsdivisionen, becoming tenuous and more one of the task rather than the division. In late November, Ludendorff ordered all of the armies on the Western Front to adopt the new system.[50]

Cambrai, 1918 and post-war

German defensive battle tactics reached their culmination at the Third Battle of Ypres; the counter-offensive at Cambrai was a conventional Gegenangriff and in 1918, minor changes to nomenclature and the Vorfeld and Hauptwiederstandslinie system, were made because of mechanisation within the army. The Vorpostenfeld (outpost zone) became the Kampffeld (advanced battle zone) at the front, with the Hauptkampffeld (main battle zone), the Grosskampffeld (greater battle zone), the Rückwärtige Stellung (rear position) further back then the Rückwärtiges Kampffeld (rear battle zone). Eingreif divisions were based from 10,000–12,000 yd (5.7–6.8 mi; 9.1–11.0 km) behind the front line and expected to fight the main defensive battle in the Grosskampffeld. The Kampffeld was held with as few troops as possible, exploiting flanking fire from machine-guns and single field guns. The front line was along the forward edge of the Grosskampffeld and covered the field artillery positions supporting the troops in the Kapmpffeld. Further back were positions for the counter-attack troops of the Stellungsdivision, to provide time for the Eingreif divisions to close up and counter-attack along with the local reserves.[51]

On 20 July 1918, Ludendorff sent Loßberg to report on the conditions in the Marne Salient, who found that the system devised for the operations in Flanders in 1917 was unworkable in the terrain of the Vesle and Aisne valleys. The unspoilt countryside was full of trees and standing crops; terrain dispersed defences were incapable of resisting tank attacks from the flanks and rear with so much cover for the attackers. Defences were changed back a line of observation groups in front of the main line of resistance, the groups having increased firepower, to force an attacker to deploy sooner. Delaying actions, moving back through lines of observation were developed into a holding action (hinhaltendes gefecht).[52]

The relative success of the defensive system at Ypres in 1917 was not repeated in 1918 on the Santerre in Picardy or the downlands west of Cambrai. The Vorpostenfeld could be overrun behind creeping barrages at night or in twilight and there were too few Eingreif divisions to counter-attack, those present being capable only of local attacks or reinforcement of the defenders. German divisions were smaller than earlier in the war, had more machine-guns and better command arrangements but the system of linked Stellungsdivisionen and Eingreifdivisionen was most demanding of manpower; British attacks in late 1918 rarely outnumbered the defenders, relying on initiative and surprise.[52]

Writing in 1939, Wynne described contemporary German defensive principles that resembled the defence of Flanders in 1917, with the depth of the defensive position increased to about 30 mi (48 km) filled with lines of resistance (Sicherungs-Widerstandslinie) from which to fight a delaying action. Static defences would be backed by mechanised and motorised Eingreif divisions ready to use speed, firepower and shock in a Gegenstoss auf der Tiefe (counter-attack from the deep). Inside the defensive position, anti-aircraft, anti-tank guns and mobile anti-tank guns would inflict losses on the opposing tanks and aircraft that were supporting the infantry attack but the fixed defences of the Siegfried Line were less important than the "flashing sword of retaliation".[53]

Notes

- ↑ Ludendorff credited Colonel Max Bauer and Captain Hermann Geyer with authorship and in 1995, Lupfer wrote that it was a collective effort of the General Staff, including Colonel Max Bauer, Major Georg Wetzell and Captain Hermann Geyer.[5][6]

- ↑ In the Second Army area south of the plateau at La Basse Ville, a powerful attack at 3:30 p.m. was repulsed by the New Zealand Division. X Corps also managed to hold its gains around Klein Zillibeke against a big German attack at 7:00 p.m.[30]

Footnotes

- 1 2 Wynne 1976, pp. 100–101.

- ↑ Wynne 1976, pp. 100–103.

- ↑ Samuels 2003, p. 179.

- ↑ Ludendorff 2005, p. 458; Lupfer 1981, p. 45.

- ↑ Ludendorff 2005, p. 458.

- ↑ Lupfer 1981, p. 45.

- ↑ Wynne 1976, pp. 149–151.

- ↑ Samuels 2003, p. 181.

- ↑ Wynne 1976, p. 161.

- ↑ Wynne 1976, pp. 152–156.

- 1 2 Samuels 2003, p. 183.

- ↑ Wynne 1976, pp. 184–185.

- ↑ Edmonds 1991, p. 143.

- 1 2 Wynne 1976, pp. 156–158.

- ↑ Wynne 1976, pp. 157–158.

- ↑ Samuels 2003, pp. 184–186.

- ↑ Wynne 1976, p. 162.

- ↑ Wynne 1976, pp. 269–270.

- ↑ Lucas & Schmieschek 2015, pp. 132, 146–148.

- ↑ Sheldon 2007, pp. 99–100.

- ↑ Zabecki 2004, p. 67.

- ↑ Samuels 2003, pp. 196–197.

- ↑ Balck 2010, p. 160.

- ↑ Harris 2008, p. 366.

- ↑ Edmonds 1991, p. 169.

- ↑ Edmonds 1991, sketch 13.

- ↑ Terraine 1977, pp. 94–95.

- ↑ Edmonds 1991, pp. 173–174.

- ↑ Edmonds 1991, p. 174.

- 1 2 Edmonds 1991, pp. 176–177.

- ↑ Wynne 1976, p. 290.

- 1 2 Rogers 2010, p. 168.

- ↑ Rogers 2010, p. 170.

- ↑ Edmonds 1991, p. 295.

- ↑ Sheldon 2007, p. 184.

- ↑ Edmonds 1991, pp. 294–295.

- ↑ Liddle 1997, pp. 45–58.

- ↑ Terraine 1977, pp. 278–279.

- ↑ Wynne 1976, pp. 307–308.

- ↑ Wynne 1976, p. 307.

- ↑ Sheldon 2007, pp. 190–191.

- ↑ Sheldon 2007, pp. 184–186.

- ↑ Terraine 1977, p. 278.

- ↑ Edmonds 1991, p. 318.

- ↑ Freeman 2011, pp. 70–71.

- 1 2 Sheldon 2007, pp. 242, 270, 291.

- ↑ Wynne 1976, p. 309.

- ↑ Bax & Boraston 2001, pp. 162–163.

- 1 2 Wynne 1976, p. 310.

- ↑ Wynne 1976, pp. 311–315.

- ↑ Edmonds & Maxwell-Hyslop 1993, p. 12.

- 1 2 Edmonds & Maxwell-Hyslop 1993, pp. 12–13.

- ↑ Wynne 1976, pp. 322, 315, 324.

References

Books

- Balck, W. (2010) [1922]. Development of Tactics, World War (facs. repr. Kessinger, LaVergne, TN ed.). Fort Leavenworth: General Service Schools Press. ISBN 978-1-4368-2099-8.

- Bax, C. E. O.; Boraston, J. H. (2001) [1926]. Eighth Division in War 1914–1918 (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Medici Society. ISBN 978-1-897632-67-3.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1991) [1948]. Military Operations France and Belgium 1917: 7 June – 10 November. Messines and Third Ypres (Passchendaele). History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. II (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-89839-166-4.

- Edmonds, J. E.; Maxwell-Hyslop, R. (1993) [1947]. Military Operations France and Belgium 1918: 26th September – 11th November The Advance to Victory. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. V (Imperial War Museum & Battery Press ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-89839-192-3.

- Harris, J. P. (2008). Douglas Haig and the First World War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89802-7.

- Liddle, P. H. (1997). Passchendaele in Perspective: The Third Battle of Ypres. London: Pen & Sword. ISBN 978-0-85052-588-5.

- Lucas, A.; Schmieschek, J. (2015). Fighting the Kaiser's War: The Saxons in Flanders 1914/1918. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-78346-300-8.

- Ludendorff, E. (2005) [1919]. My War Memories 1914–1918 (Naval & Military Press ed.). New York: Harper & Bros. ISBN 978-1-84574-303-1.

- Lupfer, T. (1981). The Dynamics of Doctrine: The Change in German Tactical Doctrine During the First World War (PDF). Fort Leavenworth: US Army Command and General Staff College. OCLC 8189258. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 4 October 2015 – via Archive Foundation.

- Rogers, D., ed. (2010). Landrecies to Cambrai: Case Studies of German Offensive and Defensive Operations on the Western Front 1914–17. Solihull: Helion. ISBN 978-1-906033-76-7.

- Samuels, M. (2003) [1995]. Command or Control? Command, Training and Tactics in the British and German Armies 1888–1918. London: Frank Cass. ISBN 978-0-7146-4214-7.

- Sheldon, J. (2007). The German Army at Passchendaele. Barnsley: Pen and Sword Books. ISBN 978-1-84415-564-4.

- Terraine, J. (1977). The Road to Passchendaele: The Flanders Offensive 1917, A Study in Inevitability. London: Leo Cooper. ISBN 978-0-436-51732-7.

- Wynne, G. C. (1976) [1939]. If Germany Attacks: The Battle in Depth in the West (Greenwood Press, NY ed.). London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-8371-5029-1.

Theses

- Freeman, J. (2011). A Planned Massacre? British Intelligence Analysis and the German Army at the Battle of Broodseinde, 4 October 1917 (PhD). Birmingham University. OCLC 767827490. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- Zabecki, D. T. (2004). Operational Art and the German 1918 Offensives (PhD). Cranfield: Cranfield University. hdl:1826/3897. OCLC 500040396. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

Further reading

- Condell, B.; Zabecki, D. T., eds. (2001). On the German Art of War: "Truppenführung" [Heeresdienstvorschrift 300 Band 1: 1933, Band 2: 1934]. Foreword by James S. Corum. Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Riener. ISBN 978-1-55587-996-9. LCCN 2001019798.

- Falls, C. (1992) [1940]. Military Operations France and Belgium 1917: The German Retreat to the Hindenburg Line and the Battles of Arras. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. I (Imperial War Museum and & Battery Press ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 0-89839-180-6.