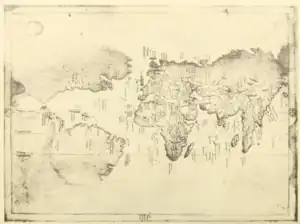

The Egerton 2803 world map / photographic facsimile in Stevenson 1911 / via IA | |

The New World in the Egerton 2803 maps / 1910–1911 composite of photographic facsimiles by EL Stevenson / via BLR | |

| General | |

|---|---|

| Type | Portolan charts |

| Date | ca 1508 or ca 1510 |

| Attribution | Visconte Maggiolo |

| Details | |

| Drafted | |

| Drafter |

|

| Location | Egerton MS 2803, Egerton Collection, British Library |

| Number of charts | 20 |

| Medium | multichrome ink and pigment on 11 vellum folios |

| Dimensions | 11 × 8 1⁄10 in (30 × 20 6⁄10 cm) |

| Coverage | World |

| Known for |

|

| cf [n 1] | |

The Egerton 2803 maps are an atlas of twenty Genoese portolan charts dated to around 1508 or 1510 and attributed to Visconte Maggiolo. The manuscript maps depict various regions of the Old and New Worlds, blending both Spanish and Portuguese cartographic knowledge. They have been noted as the earliest non-Amerindian maps of Middle America, and, jointly, as one of the oldest portolan atlases of the Americas. The maps were acquired for the Egerton Collection in 1895, published in facsimile form in 1911, and are now held by the British Library in London, England.[n 2]

History

Very little is definitively known of the atlas's provenance, as its containing manuscript collection, Egerton MS 2803, entitled Atlas of Portolan Charts, is neither signed nor dated.[1] The historian Edward L Stevenson suggested Maggiolo in 1508 as the atlas's possible origin, based on certain author-characterising features in several charts, and dates in the astronomical tables which follow the atlas within the collection.[1] Prior to Stevenson, the historian Henry Harrisse had suggested 1507, while Johannes Denucé had suggested 1510, arguing that its toponyms indicate a post-Pinzon–Solis voyage composition.[2][n 3]

The manuscript collection containing the atlas was acquired by the British Museum in 1895.[1] Facsimile copies of all folios were first taken by Stevenson and published in 1911 by the Hispanic Society of America.[3]

Contents

Each portolan features a central 32-wind compass rose, but its windrose network lacks the usual ring of 16 vertices, and is imprecisely drawn.[1] Some parallels are marked.[4] Toponyms are written in Greek, Latin, Italian.[5] Coastlines are rather faithfully renderred for the Old World, and somewhat less accurately for the New World.[6]

Analysis

The maps are thought to depict recent discoveries from the fourth voyage of Columbus, Pinzon–Solis voyage, Vespucci voyages to South America, Corte-Real voyages to Labrador, and Gama–Cabral voyages to Africa and the Indian Ocean.[7] The nomenclature of Central and South America, in particular, 'is infinitely richer and more complete than any other map of the Americas known to us until those of Diego Ribeiro of 1527 and 1529.'[8][n 6] Denucé showed the maps included, without omission, all toponyms from the Pinzon–Solis voyage, the Peter Martyr map, and still 'dozens more whose precise source is unknown.'[8]

Stevenson suggested the atlas might be 'not only the oldest known Portolan Atlas on whose charts any part of the New World is laid down, but the oldest known atlas in which the coast regions of a very large part of the entire world are represented with a fair approach to accuracy.'[9][n 7] David W Tilton deemed it the earliest known map to 'show a coastline west of Hispaniola that is recognisable as part of Central America.'[10] Arthur Davies concluded the atlas 'provides in its charts of the world the first complete and up to date summary of Portuguese and Spanish explorations to that time.'[11]

Stevenson notes a 'striking resemblance' of the Indian subcontinent and Far East charts to relevant portions of the Cantino, Canerio, and Waldseemüller Carta Marina maps.[1][n 8] Siebold notes the maps seem to imply that the Americas are joined onto Asia, which concept 'is utterly different from Portuguese cosmography and maps,' thereby suggesting 'a Spanish and not a Portuguese origin.'[12] Simonetta Conti similarly notes, 'it is clear that they [the mapmaker] must have been very familiar with the work of the Padron Real 's first authors, as can be seen from the large number of toponyms stretching from the area near Yucatan to the lands of Santa Cruz.'[13][n 9]

See also

- Padrao Real, contemporary Portuguese master map

Notes and references

Explanatory footnotes

- ↑ Drafted in Ferrar 2020, pp. 8–11, Siebold 2019, p. 1, Davies 1954, p. 47; drafter in Ferrar 2020, pp. 8–10, McIntosh 2015, pp. 52, 81; known for in Tilton 1993, p. 33; these and remaining details in British Library online catalogue entry for Egerton MS 2803.

- ↑ Called Egerton MS 2803 atlas in McIntosh 2015, p. 6; Egerton Atlas in Tilton 1993, pp. 36, 39; Egerton MS 2803 map in Davies 1954, p. 47.

- ↑ Armando Cortesão, Arthur Davies, and Jim Siebold follow the Denucé date, these last two further suggesting 1513 as the upper bound, noting 'no trace in the detailed charts of Balboa's discovery of the South Sea in 1513' (Siebold 2019, p. 1, Davies 1954, p. 47). Conti 2011, pp. 37, 43–45 does not explicity espouse a date, but in p. 45 notes the maps were 'certainly the result, by the cartographer, of knowledge not only of the fourth voyage of Columbus, but certainly, according to its toponyms, of the voyage of Solís, Pinzón, and Pedro de Ledesma of 1508–1509.' Ferrar 2020, p. 1 follows the Harrisse dating, assuming the aforementioned astronomical tables, which start on January 1508, offer predictions rather than historical data. Regarding authorship, Conti 2011, p. 45, fn. 24 notes the maps have at times been attributed to Francesco Rosselli, but dismisses this as very unlikely. Ferrar 2020, pp. 8–10 discusses toponymic evidence in favour of a Genoese provenance, deeming it strong, and in pp. 10-11 discusses authorship, deeming evidence inconclusive, but accepting a draughtsman from the Maggiolo or Pareto families as probable. McIntosh 2015, p. 6 dates the maps to circa 1508–1513, and in pp. 52, 81 tentatively suggests a Venetian rather than Genoese maker. Davies 1954, p. 51 notes 'many believe' the maps are the handiwork of Maggiolo.

- ↑ In Stevenson 1911, tab. contents and BL catalogue entry.

- ↑ Including the Septem civitates toponym on mainland between Nova Scotia and Gulf of Mexico, which Dulmo claimed to have found in 1486, which John Cabot named to Pedro Ayala in 1497, and which subsequently appeared in the 1500 de la Cosa map, this last per Jomard by Rambielinsky (Siebold 2019, p. 3, Davies 1954, p. 48).

- ↑ Siebold 2019, p. 2 notes the maps provide 171 toponyms for the mainland Central and South America, compared to the 34 on the 1500 Cosa map, 58 on the 1515 Freducci map, and 35 on the 1519 Reinel map.

- ↑ Siebold 2019, p. 2 notes '[t]he charts of Europe are unsurpassed for their time.'

- ↑ In a recent monograph, Gregory C McIntosh primarily argues that the Egerton 2803 maps, as well as the 1504 Fano–Maggiolo, 1504–1505 Kunstmann II, and circa 1505–1510 Pesaro maps all source Old World content from the 1502 Cantino map, introduced to Genoa in November 1502, and popularised via its 'highly influential' circa 1503–1504 copy by Nicolay de Caverio (McIntosh 2015, preface).

- ↑ Ferrar 2020, p. 5 likewise deems the Padron Real a source for the maps.

Short citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 Stevenson 1911, foreword.

- ↑ Siebold 2019, p. 1; Davies 1954, p. 47.

- ↑ Davies 1954, p. 47.

- ↑ Siebold 2019, p. 2.

- ↑ Ferrar 2020, pp. 1–2; Siebold 2019, p. 1.

- ↑ Siebold 2019, pp. 2, 4; Davies 1954, pp. 47–48; Stevenson 1911, foreword.

- ↑ Ferrar 2020, p. 1; Siebold 2019, p. 1; Conti 2011, p. 45.

- 1 2 Siebold 2019, p. 3; Davies 1954, p. 48.

- ↑ Davies 1954, p. 47; Stevenson 1911, foreword.

- ↑ Tilton 1993, p. 33.

- ↑ Davies 1954, p. 52.

- ↑ Siebold 2019, pp. 2–3; Davies 1954, p. 48.

- ↑ Conti 2011, p. 45.

Full citations

- Bagnoli L (2002). "Il manoscritto Egerton 2803 della British Library ed il Nuovo Mondo". Studi e Ricerche di Geografia. 25: 81–110. ISSN 2239-8236.

- Conti S (2011). "El cuarto viaje de Colon y las primeras posesiones españolas en Tierra Firme según algunos mapas del siglo XVI". Revista de estudios colombinos. 7: 35–48. ISSN 1699-3926.

- Davies A (1954). "The Egerton MS. 2803 Map and the Padrón Real of Spain in 1510". Imago Mundi. 11: 47–52. doi:10.1080/03085695408592057. JSTOR 1150174.

- Denucé J (1910). "The Discovery of the North Coast of South America According to an Anonymous Map in the British Museum". Geographical Journal. 36 (1): 65–80. doi:10.2307/1777655. JSTOR 1777655.

- Ferrar MJ (February 2020). "B.L. Egerton MS 2803 Atlas; Anon! The Construct and Possible Author". Cartography Unchained (Blog). pp. 1–12. Paper No. ChEGE/1.

- McIntosh GC (2015) [first published 2013 by Plus Ultra]. The Vesconte Maggiolo World Map of 1504 in Fano, Italy (2nd ed.). Long Beach, California: Plus Ultra. ISBN 978-0-96-674623-5.

- Roukema E (1960). "The coasts of North‐East Brazil and the guianas in the Egerton Ms. 2803". Imago Mundi. 15: 27–31. doi:10.1080/03085696008592174.

- Siebold J (2019). "Egerton Portolan Atlas, 1508". Renaissance Maps: 1490-1800 (Blog). pp. 1–12. Monograph No. 312.

- Stevenson EL, ed. (1911). Atlas of Portolan Charts: Facsimile of Manuscript in British Museum. New York: Hispanic Society of America. hdl:2027/uc1.c008586865. LCCN map11000003. IA atlasofportolanc00magg.

- Tilton DW (1993). "Latitudes, Errors and the Northern Limit of the 1508 Pinzón and Solís Voyage". Terrae Incognitae. 25: 25–40. doi:10.1179/tin.1993.25.1.25.