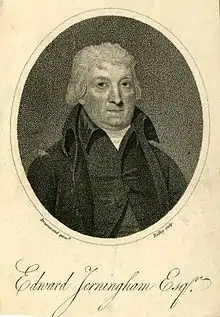

Edward Jerningham was a poet who moved in high society during the second half of the 18th century. Born at the family home of Costessey Park in 1737, he died in London on 17 November 1812. A writer of liberal views, he was savagely satirised later in life.

Life

Edward Jerningham was the third son of Sir George Jerningham and belonged to a family which had lived in Norfolk since Tudor times. Since they were Roman Catholic, he was educated first at the English College at Douai in France, and afterwards in Paris. In September 1761 he came to England to be present at the coronation of George III and brought with him a fair knowledge of Greek and Latin and a thorough mastery of French and Italian. Having an interest in religion, he examined the points of difference between Anglicanism and the Catholic Church and eventually adopted the former during the 1790s. He corresponded with Anna Seward on religious subjects[1] and at the end of his life wrote some theological works.[2]

Belonging to the family of a baronet, he moved in high society, having among his chief friends Lords Chesterfield, Harcourt, Carlisle, and Horace Walpole - who often referred to him as ‘the charming man’. He was also a friend of the Prince Regent, at whose request he arranged the library then kept at the Brighton Pavilion. Their relations were close enough for Jerningham to act as go-between during the affair between Lady Jersey and the Prince.[3] His poetry went through several editions and his work also included four plays: Margaret of Anjou: an historical interlude (1777),[4] the tragedy The Siege of Berwick (1794),[5] and the comedies The Welch Heiress (1795)[6] and The Peckham Frolic: or Nell Gwyn (1799).[7] The first three were acted without much success and the last was never performed. In the theatre world he was a particular friend of Richard Brinsley Sheridan, who nevertheless is said to have caricatured him as Sir Benjamin Backbite in The School for Scandal (1777).[8]

Poetry

“Jerningham is a literary magpie whose poetry is overwrought with allusive echoes of other poets,” comments a modern critic,[9] only echoing the opinion of Jerningham's contemporaries. Fanny Burney, for example, mentioned to one of her correspondents in 1780 that “I have been reading his poems, if his they may be called”;[10] and even his friend Horace Walpole admitted “in truth he has no genius: there is no novelty, no plan and no suite in his poetry; though many of the lines are pretty”.[11] He was a good imitator, however, and even something of a literary barometer, straddling the transition from Augustan literature to early Romanticism, which explains his interest to students of his period today.

At the outset of his literary career, Jerningham mixed with the circle about Thomas Gray, although he never met the poet himself.[12] However, like many at the time, he began by writing a close imitation of Gray's Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard in "The Nunnery” (1762).[13] Jerningham then followed it up in successive years with other poems on similar themes in which the connection with Gray's work, though less close, was maintained in theme, form and emotional tone: “The Magdalens: an elegy” (1763);[14] “The Nun: an elegy” (1764);[15] and “An Elegy Written Among the Ruins of an Abbey” (1765), which is derivative of similar use of the ruin theme in elegiac works such as Edward Moore’s “An elegy, written among the ruins of a nobleman's seat in Cornwall”.[16] Monastic themes were an obvious choice for a Catholic raised in Europe, but they are singular for being penetrated by notes of erotic passion. What is left unfulfilled in “The Nunnery”, wasting its sweetness on the desert air, is any chance of married life or sexual dalliance. And where the latter had been irregularly fulfilled, then it found a retreat in the recently opened refuge for reformed prostitutes, the setting of “The Magdalens”. There the religious connotations are intensified by Jerningham's description of its inmates “kneeling at yon rail” in “Nun-clad Penance” in the church where men of fashion such as himself went to hear them sing.[17]

The penitent male equivalent is treated in “The Funeral of Arabert, Monk of La Trappe” (1771),[18] and in the heroic epistle of “Abelard to Eloisa” (1792),[19] which serves as a pendant to Pope's earlier “Eloisa to Abelard” and, like it, is written in couplets. Jerningham's use of this theme introduces another of the questions surrounding his originality. There had already been nine poetical replies in Abelard's name to Pope's original epistle, stretching from 1720 to 1785, but his is singular in stressing the historical background to Abelard's story. Although the material was available, as it was to Pope, in John Hughes’ Letters of Abelard and Heloise: with a particular account of their lives, amours, and misfortune,[20] no one before him had thought to include the quarrel with Bernard of Clairvaux and the indictment for heresy as among the pressures that Abelard was under. An analogous case is another of Jerningham’s heroic epistles, “Yarico to Inkle” (1766), of which there had also been several other examples under that title in the four decades before his appeared.[21] The original story concerned an “Indian maid” who had saved a shipwrecked mariner on the North American coast and was subsequently sold by him into slavery. Jerningham's contribution was to shift the story into the context of the growing movement against the slave trade by making Yarico an African negro who draws attention to the anomaly in Christian doctrine that allows such discrimination against those of another race.[22]

One example of the transitional nature of Jerningham's work is found in his “Enthusiasm”,[23] a quasi-philosophical poem in which the “Enthusiastic Maid, Daughter of Energy” is put on trial in a heaven for her bad effect on the progress of civilization. In the first half of the poem, a prosecuting seraph condemns her as the cause of the Muslim burning of the Alexandrian library and the Catholic massacres and persecution of Protestants in France. In the second part she is defended as inspiring the spirit of self-sacrifice, the signing of Magna Carta, and the defiance of received ideas as exemplified by Christopher Columbus and Martin Luther. At the end she clinches the argument with the example of America's self-liberation, an instance of libertarian thinking that would very shortly be regarded as treasonable in the wake of the reaction to the French Revolution.

The poem had its admirers, but one contemporary review found it too prosaic in developing its thesis.[24] Though it is argued there that the poetry is insufficient to encompass its subject, it is rather poetical convention that impedes the meaning. Most historical allusions in “Enthusiasm” are so clothed in obscurity that they have to be identified by footnotes, and the heavenly landscape is encumbered with such abstractions borrowed from the odes of Gray and William Collins as “Meek Toleration, heav’n-descending Maid” and Superstition who “Extends, in thunder cloath’d, her threat’ning arm”. But it is only the change in versification that divides Jerningham's championship of the significance of the American revolution from William Blake’s just four years later in America: A Prophecy (1793). Otherwise the veiled manner and personified abstractions remain much the same.[25]

It is Jerningham’s meditative description of “Tintern Abbey” (1796)[26] that indicates most vividly the interface between a past manner and what was to come immediately after in William Wordsworth’s “Lines written a few miles above Tintern Abbey” (1798). Jerningham’s poem is a work of elegiac antiquarianism not very different from descriptions by other poets of the time[27] and with the same aesthetic appreciation of the melancholy scene as is found in J. M. W. Turner’s 1794 watercolour of the abbey ruins (see opposite). Wordsworth pays sly homage to this almost obligatory sensibility by interpreting the “wreaths of smoke” rising from the local ironworks as possible evidence “of some Hermit’s cave” upslope.[28] But otherwise he turns his back on both past and present and perceives the natural landscape as having an eternal moral force that resonates in the imagination.[29] The contrast could not be stronger.

An object of satire

An injudicious victim of his good nature, Jerningham twice responded to requests for poetical contributions from the leaders of literary cliques that were objects of ridicule. As a visitor to fashionable Bath, he was approached by Anna, Lady Miller and submitted “Dissipation”[30] to the fourth volume of the anthology of works from her Batheaston circle. Already the focus of satire, the death of its patroness in 1781 brought it to an end before Jerningham's reputation came to much harm.[31]

A decade later, he was recruited to help reverse the failing fortunes of the Della Cruscans,[32] the members of which, like the Batheaston set, made themselves ridiculous by the practice of mutual admiration. Writing under the name of ‘Benedict’, he published a number of sonnets imitative of the Robert Merry – Hannah Cowley exchanges in their earlier collection, The Poetry of the World (1788), and these were published in a new collection, The British Album (1790).[33]

Not only were the works of the Della Cruscans voluminous and uncritical, but they were also identified with the radical cause and so became the object of the reactionary William Gifford’s bitter satire. At the start of his attack on the group in The Baviad (1794), Gifford makes “Some sniv’lling Jerningham at fifty weep/ O’er love-lorn oxen and deserted sheep,”[34] and the reputation of weak sentimentality was to stick to him for the next two centuries. One of Jerningham's friends, at least, had no idea what Gifford was talking about. The attack "shows that he certainly was not acquainted with Mr Jerningham’s works", commented John Taylor; "he speaks of him as a pastoral poet, though Mr Jerningham has not one pastoral poem in all his numerous productions."[35] But though the poet retorted with a satire of his own,[36] his self-defence is forgotten now and Gifford's disinformation still remains largely unchallenged.

References

- ↑ Teresa Barnard, Anna Seward: a constructed life, Ashgate Publishing 2009, p.1 Archived 2015-05-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Taylor, pp.167-8

- ↑ Oxford DNB

- ↑ 18th Century Collections Online

- ↑ Google Books

- ↑ 18th Century Collections Online

- ↑ 18th Century Collections Online

- ↑ Oxford DNB

- ↑ Frank Felsenstein, English Trader, Indian Maid, Johns Hopkins University 1999, p.154

- ↑ Bettany, p.8

- ↑ 26 February 1791: The Letters of Horace Walpole, London 1840, Vol.6 p.406

- ↑ Bettany, p.6

- ↑ Google Books

- ↑ Google Books

- ↑ Oxford Text Archive

- ↑ Moore's Poetical Works, pp.131-3

- ↑ Susan Haskins, Mary Magdalen: Myth and Metaphor, HarperCollins 1993, pp.309-14

- ↑ Online archive

- ↑ Poems and Plays, Vol.2, pp.75-89)

- ↑ Google Books

- ↑ Frank Felsenstein, English Trader, Indian Maid: Representing Gender, Race, and Slavery in the New World: An Inkle and Yarico Reader, Johns Hopkins University 1999

- ↑ Poems and Plays vol. 1, pp.13-25

- ↑ Poems and Plays vol.2, pp.95-130

- ↑ The Monthly Review vol.80,pp.239-41

- ↑ A Companion to 18th Century Poetry, Wiley-Blackwell 2013, “Byrom and Jerningham: Two poems named Enthusiasm” and “Postscript: Blake”

- ↑ Poems and Plays, Vol.2, p.135)

- ↑ The language of sense, poetical Tintern, University of Michigan

- ↑ "Industrial Tintern"

- ↑ Crystal B. Lake, "The Life of Things at Tintern Abbey", Review of English Studies (2012) 63 (260): 444-465

- ↑ Poems and Plays vol.2, pp.140-42

- ↑ Philippa Bishop, “The Sentence of Momus: satirical verse and prints in 18th century Bath” (1994), pp.70-71 Archived 2015-05-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ W.N. Hargreaves-Mawdsley, The English Della Cruscans and their Time, The Hague NL, 1967, pp.182-3

- ↑ vol.2, pp.91-9

- ↑ p.7

- ↑ Taylor, p.165

- ↑ "Lines on The Baviad and The Pursuits of Literature", Poems & Plays, vol.4, pp.94-111

Bibliography

- Bettany, Lewis, Edward Jerningham and his friends: a series of 18th century letters, London 1919

- New Cambridge Bibliography of English Literature: Volume 2, 1660-1800, Cambridge University 1971, 661-2

- Courtney, William Prideaux (1892). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 29. pp. 346–347.

- Jerningham, Edward, Poems and Plays, London 1806, Volume 1; Volume 2; Vol.3; Volume 4

- Taylor, John, Records of my Life, London 1832, Chapter 13

External links

- Edward Jerningham at the Eighteenth-Century Poetry Archive (ECPA)