| Middle Korean | |

|---|---|

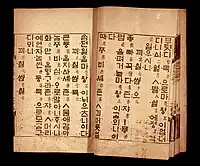

"Songs of the Moon Shining on a Thousand Rivers" (Worin Cheongang Jigok, 1447), a collection of Buddhist hymns composed by King Sejong | |

| Region | Korea |

| Era | 11th–16th centuries |

Koreanic

| |

Early forms | |

| Hanja (Idu, Hyangchal, Gugyeol), Hangul | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | okm |

okm | |

| Glottolog | midd1372 |

| Korean name | |

| Hangul | 중세 한국어 |

| Hanja | 中世韓國語 |

| Revised Romanization | Jungse hangugeo |

| McCune–Reischauer | Chungse han'gugŏ |

| North Korean name | |

| Hangul | 중세 조선어 |

| Hanja | 中世朝鮮語 |

| Revised Romanization | Jungse joseoneo |

| McCune–Reischauer | Chungse chosŏnŏ |

Middle Korean is the period in the history of the Korean language succeeding Old Korean and yielding in 1600 to the Modern period. The boundary between the Old and Middle periods is traditionally identified with the establishment of Goryeo in 918, but some scholars have argued for the time of the Mongol invasions of Korea (mid-13th century). Middle Korean is often divided into Early and Late periods corresponding to Goryeo (until 1392) and Joseon respectively. It is difficult to extract linguistic information from texts of the Early period, which are written using adaptations of Chinese characters. The situation was transformed in 1446 by the introduction of the Hangul alphabet, so that Late Middle Korean provides the pivotal data for the history of Korean.

Sources

Until the late 19th century, most formal writing in Korea, including government documents, scholarship and much literature, was written in Classical Chinese. Before the 15th century, the little writing in Korean was done using cumbersome adaptations of Chinese characters such as idu and hyangchal. Thus Early Middle Korean, like Old Korean before it, is sparsely documented.[1] This situation changed dramatically with the introduction of the Hangul alphabet in 1446.[2]

Before the 1970s, the key sources for EMK were a few wordlists.

- The Jilin leishi (1103–1104) was a Chinese book about Korea. All that survives of the original three volumes is a brief preface and a glossary of over 350 Korean words and phrases.[3] The Korean forms were rendered using characters whose Chinese sound provides a necessarily imprecise approximation of the Korean pronunciation.[4]

- The Cháoxiǎn guǎn yìyǔ (朝鮮館譯語, 1408) is another Chinese glossary of Korean, containing 596 Korean words.[5][6]

- The Hyangyak kugŭppang (朝鮮館譯語鄕藥救急方, mid-13th century) is a Korean survey of herbal treatments. The work is written in Chinese, but the Korean names of some 180 ingredients are rendered using Chinese characters intended to be read with their Sino-Korean pronunciations.[7]

- The Japanese text Nichū Reki (二中曆, believed to be compiled from two works from the early 12th century), contains kana transcriptions of Korean numerals, but is marred by errors.[7]

In 1973, close examination of a Buddhist sutra from the Goryeo period revealed faint interlinear annotations with simplified Chinese characters indicating how the Chinese text could be read as Korean. More examples of gugyeol ('oral embellishment') were discovered, particularly in the 1990s.[8][9] Many of the gugyeol characters were abbreviated, and some of them are identical in form and value to symbols in the Japanese katakana syllabary, though the historical relationship between the two is not yet clear.[10] An even more subtle method of annotation known as gakpil (각필, 角筆 'stylus') was discovered in 2000, consisting of dots and lines made with a stylus.[11] Both forms of annotation contain little phonological information, but are valuable sources on grammatical markers.[12]

The introduction of the Hangul alphabet in 1446 revolutionized the description of the language.[2] The Hunminjeongeum ('Correct sounds for the instruction of the people') and later texts describe the phonology and morphology of the language with great detail and precision.[13] Earlier forms of the language must be reconstructed by comparing fragmentary evidence with LMK descriptions.[2]

These works are not as informative regarding Korean syntax, as they tend to use a stilted style influenced by Classical Chinese. The best examples of colloquial Korean are the translations in foreign-language textbooks produced by the Joseon Bureau of Interpreters.[2]

Script and phonology

Hangul letters correspond closely to the phonemes of Late Middle Korean. The romanization most commonly used in linguistic writing on the history of Korean is the Yale romanization devised by Samuel Martin, which faithfully reflects the Hangul spelling.[14]

| Bilabial | Alveolar | Velar | Glottal | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | ㅁ | [m] | n | ㄴ | [n] | ng | ㆁ | [ŋ] | ||||

| Stop | plain | p | ㅂ | [p] | t | ㄷ | [t] | k | ㄱ | [k] | |||

| aspirated | ph | ㅍ | [pʰ] | th | ㅌ | [tʰ] | kh | ㅋ | [kʰ] | ||||

| tense | pp | ㅃ | [p͈] | tt | ㄸ | [t͈] | kk | ㄲ | [k͈] | ||||

| Affricate | plain | c | ㅈ | [ts] | |||||||||

| aspirated | ch | ㅊ | [tsʰ] | ||||||||||

| tense | cc | ㅉ | [t͈s] | ||||||||||

| Fricative | plain | s | ㅅ | [s] | h | ㅎ | [h] | ||||||

| tense | ss | ㅆ | [s͈] | hh | ㆅ | [h͈] | |||||||

| voiced | W | ㅸ | [β] | z | ㅿ | [z] | G | ㅇ | [ɣ] | ||||

| Liquid | l | ㄹ | [l~ɾ] | ||||||||||

The tensed stops pp, tt, cc and kk are distinct phonemes in modern Korean, but in LMK they were allophones of consonant clusters.[16] The tensed fricative hh only occurred in a single verb root, hhye- 'to pull', and has disappeared in Modern Korean.[17]

The voiced fricatives /β/, /z/ and /ɣ/ occurred only in limited environments, and are believed to have arisen from lenition of /p/, /s/ and /k/, respectively.[18][19] They have disappeared in most modern dialects, but some dialects in the southeast and northeast retain /p/, /s/ and /k/ in these words.[20]

The affricates c, ch and cc were apical consonants, as in modern northwestern dialects, rather than palatals as in modern Seoul.[21]

Late Middle Korean had a limited and skewed set of initial clusters: sp-, st-, sk-, pt-, pth-, ps-, pc-, pst- and psk-.[17][22] It is believed that they resulted from syncope of vowels o or u during the Middle Korean period. For example, the Jilin leishi has *posol (菩薩) 'rice', which became LMK psól and modern ssal.[23] A similar process is responsible for many aspirated consonants. For example, the Jilin leishi has *huku- (黒根) 'big', which became LMK and modern khu.[22]

Late Middle Korean had seven vowels:

| Front | Central | Back | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | ㅣ | [i] | u | ㅡ | [ɨ] | wu | ㅜ | [u] |

| Mid | e | ㅓ | [ə] | wo | ㅗ | [o] | |||

| Open | a | ㅏ | [a] | o | ㆍ | [ʌ] | |||

The precise phonetic values of these vowels are controversial.[24] Six of them are still distinguished in modern Korean, but only the Jeju language has a distinct reflex of o.[24] In most other varieties it has merged with a in the first syllable of a word and u elsewhere.[25] An exception is found in the Yukchin dialect in the far northeast and dialects along the south coast, where first-syllable o has merged with wo when adjacent to a labial consonant.[26]

LMK had rigid vowel harmony, described in the Hunminjeongeum by dividing the vowels into three groups:[25][27]

- yang ('bright'): a, o and wo

- yin ('dark'): e, u and wu

- neutral: i

Yang and yin vowels could not occur in the same word, but could co-occur with the neutral vowel.[25][28] The phonetic dimension underlying vowel harmony is also disputed. Lee Ki-Moon suggested that LMK vowel harmony was based on vowel height.[28] Some recent authors attribute it to advanced and retracted tongue root states.[29]

Loans from Middle Mongolian in the 13th century show several puzzling correspondences, in particular between Middle Mongolian ü and Korean u.[30] Based on these data and transcriptions in the Jilin leishi, Lee Ki-Moon argued for a Korean Vowel Shift between the 13th and 15th centuries, consisting of chain shifts involving five of these vowels:[31]

- y > u > o > ʌ

- e > ə > ɨ

William Labov found that this proposed shift followed different principles to all the other chain shifts he surveyed.[32] Lee's interpretation of both the Mongolian and Jilin leishi materials has also been challenged by several authors.[33][34]

LMK also had two glides, y [j] and w [w]:[35][36]

- A y on-glide could precede four of the vowels, indicated in Hangul with modified letters: ya ㅑ [ja], ye ㅕ [jə], ywo ㅛ [jo] and ywu ㅠ [ju].

- A w on-glide could precede a or e, written with a pair of vowel symbols: wa ㅘ [wa] and we ㅝ [wə].

- A y off-glide could follow any of the pure vowels except i or any of the six onglide-vowel combinations, and was marked by adding the letter i ⟨ㅣ⟩. In modern Korean the vowel-offglide sequences have become monophthongs.

Early Hangul texts distinguish three pitch contours on each syllable: low (unmarked), high (marked with one dot) and rising (marked with two dots).[37] The rising tone may have been longer in duration, and is believed to have arisen from a contraction of a pair of syllables with low and high tone.[38] LMK texts do not show clear distinctions after the first high or rising tone in a word, suggesting that the language had a pitch accent rather than a full tone system.[39]

Vocabulary

Although some Chinese words had previously entered Korean, Middle Korean was the period of the massive and systematic influx of Sino-Korean vocabulary.[40] As a result, over half the modern Korean lexicon consists of Sino-Korean words, though they account for only about a tenth of basic vocabulary.[41]

Classical Chinese was the language of government and scholarship in Korea from the 7th century until the Gabo Reforms of the 1890s.[42] After King Gwangjong established the gwageo civil service examinations on the Chinese model in 958, familiarity with written Chinese and the Chinese classics spread through the ruling classes.[43]

Korean literati read Chinese texts using a standardized Korean pronunciation, originally based on Middle Chinese. They used Chinese rhyme dictionaries, which specified the pronunciations of Chinese characters relative to other characters, and could thus be used to systematically construct a Sino-Korean reading for any word encountered in a Chinese text.[44] This system became so entrenched that 15th-century efforts to reform it to more closely match the Chinese pronunciation of the time were abandoned.[45]

The prestige of Chinese was further enhanced by the adoption of Confucianism as the state ideology of Joseon, and Chinese literary forms flooded into the language at all levels of society.[46] Some of these denoted items of imported culture, but it was also common to introduce Sino-Korean words that directly competed with native vocabulary.[46] Many Korean words known from Middle Korean texts have since been lost in favour of their Sino-Korean counterparts, including the following.

| Gloss | Native | Sino-Korean | Middle Chinese[lower-alpha 1] |

|---|---|---|---|

| hundred | wón 온〮 | póyk ᄇᆡᆨ〮 > payk 백 | pæk 百 |

| thousand | cúmun 즈〮믄 | chyen 쳔 > chen 천 | tshen 千 |

| river, lake | kolom ᄀᆞᄅᆞᆷ | kang 가ᇰ | kæwng 江 |

| mountain | mwoy 뫼 | san 산 | srɛn 山 |

| castle | cas 잣 | syeng 셔ᇰ > seng 성 | dzyeng 城 |

| parents | ezí 어ᅀᅵ〮 | pwúmwo 부〮모 | bjuXmuwX 父母 |

Notes

- ↑ Middle Chinese forms are given in Baxter's transcription for Middle Chinese.

References

- ↑ Sohn (2012), p. 73.

- 1 2 3 4 Lee & Ramsey (2011), p. 100.

- ↑ Yong & Peng (2008), pp. 374–375.

- ↑ Lee & Ramsey (2011), pp. 85–86.

- ↑ Sohn (2015), p. 440.

- ↑ Ogura (1926), p. 2.

- 1 2 Lee & Ramsey (2011), pp. 81.

- ↑ Lee & Ramsey (2011), p. 83.

- ↑ Nam (2012), pp. 46–48.

- ↑ Lee & Ramsey (2011), pp. 83–84.

- ↑ Lee & Ramsey (2011), p. 84.

- ↑ Lee & Ramsey (2011), p. 85.

- ↑ Sohn (2012), pp. 76–77.

- ↑ Lee & Ramsey (2011), p. 10.

- ↑ Lee & Ramsey (2011), pp. 128–153.

- ↑ Lee & Ramsey (2011), pp. 128–129.

- 1 2 Lee & Ramsey (2011), p. 130.

- ↑ Lee & Ramsey (2011), p. 64.

- ↑ Whitman (2015), p. 431.

- ↑ Lee & Ramsey (2000), pp. 320–321.

- ↑ Lee & Ramsey (2011), pp. 149–150.

- 1 2 Cho & Whitman (2019), p. 20.

- ↑ Cho & Whitman (2019), pp. 19–20.

- 1 2 3 Lee & Ramsey (2011), p. 156.

- 1 2 3 Sohn (2012), p. 81.

- ↑ Lee & Ramsey (2000), pp. 319–320.

- ↑ Lee & Ramsey (2011), pp. 161–162.

- 1 2 Lee & Ramsey (2011), p. 162.

- ↑ Sohn (2015), p. 457, n. 4.

- ↑ Lee & Ramsey (2011), p. 94.

- ↑ Lee & Ramsey (2011), pp. 94–95.

- ↑ Labov (1994), pp. 138–139.

- ↑ Whitman (2013), pp. 254–255.

- ↑ Whitman (2015), p. 429.

- ↑ Sohn (2012), pp. 81–82.

- ↑ Lee & Ramsey (2011), pp. 159–161.

- ↑ Lee & Ramsey (2011), p. 163.

- ↑ Lee & Ramsey (2011), pp. 163–165.

- ↑ Lee & Ramsey (2011), pp. 167–168.

- ↑ Sohn (2012), p. 118.

- ↑ Lee & Ramsey (2000), p. 136.

- ↑ Lee & Ramsey (2000), pp. 55–57.

- ↑ Lee & Ramsey (2011), p. 98.

- ↑ Lee & Ramsey (2011), p. 76.

- ↑ Lee & Ramsey (2000), p. 56.

- 1 2 Lee & Ramsey (2011), p. 235.

- ↑ Sohn (2012), pp. 118–119.

Works cited

- Cho, Sungdai; Whitman, John (2019), Korean: A Linguistic Introduction, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-51485-9.

- Labov, William (1994), Principles of Linguistic Change, Volume 1: Internal Factors, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Blackwell, ISBN 978-0-631-17913-9.

- Lee, Iksop; Ramsey, S. Robert (2000), The Korean Language, SUNY Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-4831-1.

- Lee, Ki-Moon; Ramsey, S. Robert (2011), A History of the Korean Language, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-139-49448-9.

- Nam, Pung-hyun (2012), "Old Korean", in Tranter, Nicolas (ed.), The Languages of Japan and Korea, Routledge, pp. 41–72, ISBN 978-0-415-46287-7.

- Ogura, S. (1926), "A Corean Vocabulary", Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, 4 (1): 1–10, doi:10.1017/S0041977X00102538, JSTOR 607397.

- Sohn, Ho-min (2012), "Middle Korean", in Tranter, Nicolas (ed.), The Languages of Japan and Korea, Routledge, pp. 73–122, ISBN 978-0-415-46287-7.

- ——— (2015), "Middle Korean and Pre-Modern Korean", in Brown, Lucien; Yeon, Jaehoon (eds.), The Handbook of Korean Linguistics, Wiley, pp. 439–458, ISBN 978-1-118-35491-9.

- Whitman, John (2013), "A History of the Korean Language, by Ki-Moon Lee and Robert Ramsey", Korean Linguistics, 15 (2): 246–260, doi:10.1075/kl.15.2.05whi.

- ——— (2015), "Old Korean", in Brown, Lucien; Yeon, Jaehoon (eds.), The Handbook of Korean Linguistics, Wiley, pp. 421–438, ISBN 978-1-118-35491-9.

- Yong, Heming; Peng, Jing (2008), Chinese lexicography: a history from 1046 BC to AD 1911, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-156167-2.