A Dvarapala or Dvarapalaka (Sanskrit, "door guard"; IAST: Dvārapāla Sanskrit pronunciation: [dʋaːɽɐpaːlɐ]) is a door or gate guardian often portrayed as a warrior or fearsome giant, usually armed with a weapon - the most common being the gada (mace). The dvarapala statue is a widespread architectural element throughout Hindu, Buddhist and Jaina cultures, as well as in areas influenced by them like Java.

Names

In most Southeast Asian languages (including Thai, Burmese, Vietnamese, Khmer and Javanese), these protective figures are referred to as dvarapala. Sanskrit dvāra means "gate" or "door", and pāla means "guard" or "protector".

The related name in Indonesian and Malaysia is dwarapala. Equivalent door guardians in northern Asian languages are Kongōrikishi or Niō in Japanese, Heng Ha Er Jiang in Chinese, and Narayeongeumgang in Korean.

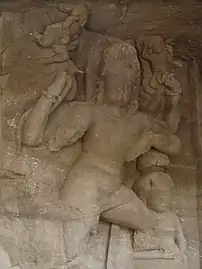

Origin and forms

Dvarapalas as an architectural feature have their origin in tutelary deities, like Yaksha and warrior figures, such as Acala, of the local popular religion.[1] Today some dvarapalas are even figures of policemen or soldiers standing guard.

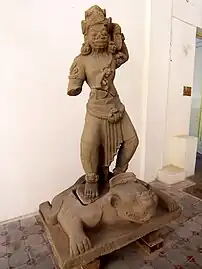

These statues were traditionally placed outside Hindu temples or Buddhist temples, as well as other structures like royal palaces, to protect the holy places inside. A dvarapala is usually portrayed as an armed fearsome guardian looking like a demon, but at the gates of Buddhist temples in Sri Lanka, dvarapalas often display average human features. In other instances a fierce-looking nāga snake figure may perform the same function. Dvarapalas are present in almost all Hindu temples, Dvarapalas are highly important in Vaishnavism and called as Jaya-Vijaya who are the guardians or (gatekeepers) of the abode of Vishnu, known as Vaikuntha (meaning place of eternal bliss).[2][3] They are present in almost all Vaishnavite temples and they are mentioned in several Hindu scriptures like Brahmanda Purana and Srimad Bagavatham. According to the Brahmanda Purana, Jaya and Vijaya were the sons of Kali, an Asura, and Kali, in turn, was one of the sons of Varuna and his wife, Stuta (Sanskrit (स्तुत, meaning 'praise').[4][5]

The sculptures in Java and Bali, usually carved from andesite, portray dvarapalas as fearsome giants with a rather bulky physique in semi kneeling position and holding a club. The largest dvarapala stone statue in Java, a dvarapala of the Singhasari period, is 3.7 metres (12 ft) tall. The traditional dvarapalas of Cambodia and Thailand, on the other hand, are leaner and portrayed in a standing position holding the club downward in the center.

The ancient sculpture of dvarapala in Thailand is made of a high-fired stoneware clay covered with a pale, almost milky celadon glaze. Ceramic sculptures of this type were produced in Thailand, during the Sukhothai and Ayutthaya periods, between the 14th and 16th centuries, at several kiln complexes located in northern Thailand. [6]

Depending on the size and wealth of the temple, the guardians could be placed singly, in pairs or in larger groups. Smaller structures may have had only one dvarapala. Often there was a pair placed on either side of the threshold to the shrine.[7] Some larger sites may have had four (lokapālas, guardians of the four cardinal directions), eight, or 12. In some cases only the fierce face or head of the guardian is represented, a figure very common in the kratons in Java.

Dvarapala in Sri Kalyana Ramaswamy temple, Tamil Nadu, India.

Dvarapala in Sri Kalyana Ramaswamy temple, Tamil Nadu, India. The largest dvarapala stone statue of Java, Singhasari period.

The largest dvarapala stone statue of Java, Singhasari period.

Contemporary soldier dvarapala as doorkeeper at Wat Ratchabophit, Bangkok

Contemporary soldier dvarapala as doorkeeper at Wat Ratchabophit, Bangkok.jpg.webp) Dvarapala at the entrance of Hatadage, Polonnaruwa, Sri Lanka

Dvarapala at the entrance of Hatadage, Polonnaruwa, Sri Lanka Dvarapala at the Kraton of Surakarta, Indonesia

Dvarapala at the Kraton of Surakarta, Indonesia Dvarapalaka, 11th century (Chola dynasty), Tamil Nadu, India

Dvarapalaka, 11th century (Chola dynasty), Tamil Nadu, India_statue_at_Hindu_temple.jpg.webp) Guardian statue at a Hindu temple in Sri Lanka.

Guardian statue at a Hindu temple in Sri Lanka. Pair of Dvarapala at Chaturmukha Basadi, India

Pair of Dvarapala at Chaturmukha Basadi, India.jpg.webp) Dwaarpalas at a Jain temple

Dwaarpalas at a Jain temple.jpg.webp) Dwaarpalas at a Jain temple

Dwaarpalas at a Jain temple

See also

References

- ↑ Helena A. van Bemmel, Dvārapālas in Indonesia: temple guardians and acculturation By Helena A. van Bemmel, ISBN 978-90-5410-155-0

- ↑ Bhattacharji, Sukumari (1998). Legends of Devi. Orient Blackswan. p. 16.

- ↑ Gregor Maehle (2012). Ashtanga Yoga The Intermediate Series: Mythology, Anatomy, and Practice. New World Library. p. 34.

- ↑ G.V.Tagare (1958). Brahmanda Purana – English Translation – Part 3 of 5. pp. 794.

- ↑ www.wisdomlib.org (2017-10-09). "Stuta, Stutā: 5 definitions". www.wisdomlib.org. Retrieved 2020-01-15.

- ↑ Samuel P. Harn Museum of Art, Gainesville, Florida

- ↑ "Dvarapala - Chinese Buddhist Encyclopedia". www.chinabuddhismencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2020-08-12.