| Inguinal hernia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Diagram of an indirect, scrotal inguinal hernia (median view from the left). | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | General surgery |

| Symptoms | Pain, bulging in the groin[1] |

| Complications | Strangulation[1] |

| Usual onset | < 1 year old, > 50 years old[2] |

| Risk factors | Family history, smoking, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, obesity, pregnancy, peritoneal dialysis, collagen vascular disease, connective tissue disease, previous open appendectomy[1][2][3] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, medical imaging[1] |

| Treatment | Conservative, surgery[1] |

| Frequency | 27% (males), 3% (females)[1] |

| Deaths | 59,800 (2015)[4] |

An inguinal hernia or groin hernia, is a hernia (protrusion) of abdominal cavity contents through the inguinal canal. Symptoms, which may include pain or discomfort especially with or following coughing, exercise, or bowel movements, are absent in about a third of patients. Symptoms often get worse throughout the day and improve when lying down. A bulging area may occur that becomes larger when bearing down. Inguinal hernias occur more often on the right than left side. The main concern is strangulation, where the blood supply to part of the intestine is blocked. This usually produces severe pain and tenderness of the area.[1]

Risk factors for the development of a hernia include: smoking, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, obesity, pregnancy, peritoneal dialysis, collagen vascular disease, and previous open appendectomy, among others.[1][2] Predisposition to hernias is genetic[5] and they occur more often in certain families.[6][7][8][1] Deleterious mutations causing predisposition to hernias seem to have dominant inheritance (especially for men). It is unclear if inguinal hernias are associated with heavy lifting. Hernias can often be diagnosed based on signs and symptoms. Occasionally medical imaging is used to confirm the diagnosis or rule out other possible causes.[1]

Groin hernias that do not cause symptoms in males do not need to be repaired. Repair, however, is generally recommended in females due to the higher rate of femoral hernias (also a type of groin hernia) which have more complications. If strangulation occurs immediate surgery is required. Repair may be done by open surgery or by laparoscopic surgery. Open surgery has the benefit of possibly being done under local anesthesia rather than general anesthesia. Laparoscopic surgery generally has less pain following the procedure.[1][9]

In 2015 inguinal, femoral and abdominal hernias affected about 18.5 million people.[10] About 27% of males and 3% of females develop a groin hernia at some time in their life.[1] Groin hernias occur most often before the age of one and after the age of fifty.[2] Globally, inguinal, femoral and abdominal hernias resulted in 60,000 deaths in 2015 and 55,000 in 1990.[4][11]

Signs and symptoms

Hernias usually present as bulges in the groin area that can become more prominent when coughing, straining, or standing up. The bulge commonly disappears on lying down. Mild discomfort can develop over time. The inability to "reduce", or place the bulge back into the abdomen usually means the hernia is 'incarcerated' which requires emergency surgery.

As the hernia progresses, contents of the abdominal cavity, such as the intestines, can descend into the hernia and run the risk of being pinched within the hernia, causing an intestinal obstruction. Significant pain at the hernia site is suggestive of a more severe course, such as incarceration (the hernia cannot be reduced back into the abdomen) and subsequent ischemia and strangulation (when the hernia becomes deprived of blood supply).[12] If the blood supply of the portion of the intestine caught in the hernia is compromised, the hernia is deemed "strangulated" and gut ischemia and gangrene can result, with potentially fatal consequences. The timing of complications is not predictable.

Pathophysiology

In males, indirect hernias follow the same route as the descending testes, which migrate from the abdomen into the scrotum during the development of the urinary and reproductive organs. The larger size of their inguinal canal, which transmitted the testicle and accommodates the structures of the spermatic cord, might be one reason why men are 25 times more likely to have an inguinal hernia than women. Although several mechanisms such as strength of the posterior wall of the inguinal canal and shutter mechanisms compensating for raised intra-abdominal pressure prevent hernia formation in normal individuals, the exact importance of each factor is still under debate. The physiological school of thought thinks that the risk of hernia is due to a physiological difference between patients who develop a hernia and those who do not, namely the presence of aponeurotic extensions from the transversus abdominis aponeurotic arch.[13]

Inguinal hernias mostly contain the omentum or a part of the small intestines, however, some unusual contents may be an appendicitis, diverticulitis, colon cancer, urinary bladder, ovaries, and rarely malignant lesions.[14]

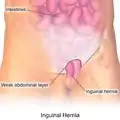

Illustration of an inguinal hernia.

Illustration of an inguinal hernia. Different types of inguinal hernias.

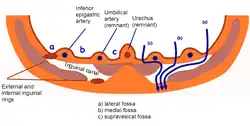

Different types of inguinal hernias. Inguinal fossae

Inguinal fossae

Diagnosis

There are two types of inguinal hernia, direct and indirect, which are defined by their relationship to the inferior epigastric vessels. Direct inguinal hernias occur medial to the inferior epigastric vessels when abdominal contents herniate through a weak spot in the fascia of the posterior wall of the inguinal canal, which is formed by the transversalis fascia. Indirect inguinal hernias occur when abdominal contents protrude through the deep inguinal ring, lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels; this may be caused by failure of embryonic closure of the processus vaginalis.

In the case of the female, the opening of the superficial inguinal ring is smaller than that of the male. As a result, the possibility for hernias through the inguinal canal in males is much greater because they have a larger opening and therefore a much weaker wall through which the intestines may protrude.

| Type | Description | Relationship to inferior epigastric vessels | Covered by internal spermatic fascia? | Usual onset |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct inguinal hernia | Enters through a weak point in the fascia of the abdominal wall (Hesselbach triangle) | Medial | No | Adult |

| Indirect inguinal hernia | Protrudes through the inguinal ring and is ultimately the result of the processus vaginalis failing to close after the testicle's passage during the embryonic stage | Lateral | Yes | Congenital / Adult |

Inguinal hernias, in turn, belong to groin hernias, which also includes femoral hernias. A femoral hernia is not via the inguinal canal, but via the femoral canal, which normally allows passage of the common femoral artery and vein from the pelvis to the leg.

In Amyand's hernia, the content of the hernial sac is the appendix.

In Littre's hernia, the content of the hernial sac contains a Meckel's diverticulum.

Clinical classification of hernia is also important according to which hernia is classified into

- Reducible hernia: is one which can be pushed back into the abdomen by putting manual pressure to it.

- Irreducible/Incarcerated hernia: is one which cannot be pushed back into the abdomen by applying manual pressure.

Irreducible hernias are further classified into

- Obstructed hernia: is one in which the lumen of the herniated part of intestine is obstructed.

- Strangulated hernia: is one in which the blood supply of the hernia contents is cut off, thus, leading to ischemia. The lumen of the intestine may be patent or not.

Direct inguinal hernia

The direct inguinal hernia enters through a weak point in the fascia of the abdominal wall, and its sac is noted to be medial to the inferior epigastric vessels. Direct inguinal hernias may occur in males or females, but males are ten times more likely to get a direct inguinal hernia.[15]

A direct inguinal hernia protrudes through a weakened area in the transversalis fascia near the medial inguinal fossa within an anatomic region known as the inguinal or Hesselbach's triangle, an area defined by the edge of the rectus abdominis muscle, the inguinal ligament and the inferior epigastric artery. These hernias are capable of exiting via the superficial inguinal ring and are unable to extend into the scrotum.

When a patient develops a simultaneous direct and indirect hernia on the same side, it is called a pantaloon hernia or saddlebag hernia because it resembles a pair of pants with the epigastric vessels in the crotch, and the defects can be repaired separately or together. Another term for pantaloon hernia is Romberg's hernia.

Since the abdominal walls weaken with age, direct hernias tend to occur in the middle-aged and elderly. This is in contrast to indirect hernias which can occur at any age including the young, since their etiology includes a congenital component where the inguinal canal is left more patent (compared to individuals less susceptible to indirect hernias).[16][17] Additional risk factors include chronic constipation, being overweight or obese, chronic cough, family history and prior episodes of direct inguinal hernias.[15]

Indirect inguinal hernia

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

An indirect inguinal hernia results from the failure of embryonic closure of the deep inguinal ring. In the male it can occur after the testicle has passed through the deep inguinal ring. It is the most common cause of groin hernia. A double indirect inguinal hernia has two sacs.

In the male fetus, the peritoneum gives a coat to the testicle as it passes through this ring, forming a temporary connection called the processus vaginalis. In normal development, the processus is obliterated once the testicle is completely descended. The permanent coat of peritoneum that remains around the testicle is called the tunica vaginalis. The testicle remains connected to its blood vessels and the vas deferens, which make up the spermatic cord and descend through the inguinal canal to the scrotum.

The deep inguinal ring, which is the beginning of the inguinal canal, remains as an opening in the fascia transversalis, which forms the fascial inner wall of the spermatic cord. When the opening is larger than necessary for passage of the spermatic cord, the stage is set for an indirect inguinal hernia. The protrusion of peritoneum through the internal inguinal ring can be considered an incomplete obliteration of the processus.

In an indirect inguinal hernia, the protrusion passes through the deep inguinal ring and is located lateral to the inferior epigastric artery. Hence, the conjoint tendon is not weakened.

There are three main types

- Bubonocele: in this case the hernia is limited in inguinal canal.

- Funicular: here the processus vaginalis is closed at its lower end just above the epididymis. The content of the hernial sac can be felt separately from the testis which lies below the hernia.

- Complete (or scrotal): here the processus vaginalis is patent throughout. The hernial sac is continuous with the tunica vaginalis of the testis. The hernia descends down to the bottom of the scrotum and it is difficult to differentiate the testis from hernia.

In the female, groin hernias are only 4% as common as in males. Indirect inguinal hernia is still the most common groin hernia for females. If a woman has an indirect inguinal hernia, her internal inguinal ring is patent, which is abnormal for females. The protrusion of peritoneum is not called "processus vaginalis" in women, as this structure is related to the migration of the testicle to the scrotum. It is simply a hernia sac. The eventual destination of the hernia contents for a woman is the labium majus on the same side, and hernias can enlarge one labium dramatically if they are allowed to progress.

Medical imaging

A physician may diagnose an inguinal hernia, as well as the type, from medical history and physical examination.[20] For confirmation or in uncertain cases, medical ultrasonography is the first choice of imaging, because it can both detect the hernia and evaluate its changes with for example pressure, standing and Valsalva maneuver.[21]

When assessed by ultrasound or cross sectional imaging with CT or MRI, the major differential in diagnosing indirect inguinal hernias is differentiation from spermatic cord lipomas, as both can contain only fat and extend along the inguinal canal into the scrotum.[22]

On axial CT, lipomas originate inferior or lateral to the cord, and are located inside the cremaster muscle, while inguinal hernias lie anteromedial to the cord and are not intramuscular. Large lipomas may appear nearly indistinguishable as the fat engulfs anatomic boundaries, but they do not change position with coughing or straining.[22]

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis of the symptoms of inguinal hernia mainly includes the following potential conditions:[23]

- Femoral hernia

- Epididymitis

- Testicular torsion

- Lipomas

- Inguinal adenopathy (Lymph node Swelling)

- Groin abscess

- Saphenous vein dilation, called Saphena varix

- Vascular aneurysm or pseudoaneurysm

- Hydrocele

- Varicocele

- Cryptorchidism (Undescended testes)

Management

Conservative

There is currently no medical recommendation about how to manage an inguinal hernia condition in adults, due to the fact that, until recently,[24][25] elective surgery used to be recommended. The hernia truss (or hernia belt) is intended to contain a reducible inguinal hernia within the abdomen. It is not considered to provide a cure, and if the pads are hard and intrude into the hernia aperture they may cause scarring and enlargement of the aperture. In addition, most trusses with older designs are not able effectively to contain the hernia at all times, because their pads do not remain permanently in contact with the hernia. The more modern variety of truss is made with non-intrusive flat pads and comes with a guarantee to hold the hernia securely during all activities. They have been described by users as providing greater confidence and comfort when carrying out physically demanding tasks. However, their use is controversial, as data to determine whether they help prevent hernia complications are lacking.[1] A truss also increases the probability of complications, which include strangulation of the hernia, atrophy of the spermatic cord, and atrophy of the fascial margins. This allows the defect to enlarge and makes subsequent repair more difficult.[26] Their popularity is nonetheless likely to increase, as many individuals with small, painless hernias are now delaying hernia surgery due to the risk of post-herniorrhaphy pain syndrome.[27] Elasticated pants used by athletes may also provide useful support for the smaller hernia.

Surgical

Surgical correction of inguinal hernias is called a hernia repair. It is not recommended in minimally symptomatic hernias, for which watchful waiting is advised, due to the risk of post herniorraphy pain syndrome. Surgery is commonly performed as outpatient surgery. There are various surgical strategies which may be considered in the planning of inguinal hernia repair. These include the consideration of mesh use (e.g. synthetic or biologic), open repair, use of laparoscopy, type of anesthesia (general or local), appropriateness of bilateral repair, etc. Mesh or non mesh repairs have both benefits in different areas, but mesh repairs may reduce the rate of hernia reappearance, visceral or neurovascular injuries, length of hospital stay and time to return to activities of daily living.[28] Laparoscopy is most commonly used for non-emergency cases; however, a minimally invasive open repair may have a lower incidence of post-operative nausea and mesh associated pain. During surgery conducted under local anaesthesia, the patient will be asked to cough and strain during the procedure to help in demonstrating that the repair is without tension and sound.[29]

(photo: United States Military Medical Archives)

The photograph is blurry as the patient was shaking too much.

Constipation after hernia repair results in strain to evacuate the bowel causing pain, and fear that the sutures may rupture. Opioid analgesia makes constipation worse. Promoting an easy bowel motion is important post-operatively.

Surgical correction is always recommended for inguinal hernias in children.[30]

Emergency surgery for incarceration and strangulation carry much higher risk than planned, "elective" procedures. However, the risk of incarceration is low, evaluated at 0.2% per year.[31] On the other hand, surgery has a risk of inguinodynia (10-12%), and this is why males with minimal symptoms are advised to watchful waiting.[31][32] However, if they experience discomfort while doing physical activities or they routinely avoid them for fear of pain, they should seek surgical evaluation.[33] For female patients, surgery is recommended even for asymptomatic patients.[34]

Epidemiology

A direct inguinal hernia is less common (~25–30% of inguinal hernias) and usually occurs in men over 40 years of age.

Men have an 8 times higher incidence of inguinal hernia than women.[35]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Fitzgibbons RJ, Jr; Forse, RA (19 February 2015). "Clinical practice. Groin hernias in adults" (PDF). The New England Journal of Medicine. 372 (8): 756–63. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1404068. PMID 25693015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 November 2021. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 Domino, Frank J. (2014). The 5-minute clinical consult 2014 (22nd ed.). Philadelphia, Pa.: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 562. ISBN 9781451188509.

- ↑ Burcharth J, Pommergaard HC, Rosenberg J (2013). "The inheritance of groin hernia: a systematic review". Hernia. 17 (2): 183–9. doi:10.1007/s10029-013-1060-4. PMID 23423330. S2CID 27799467.

- 1 2 GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators (8 October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- ↑ Öberg, S.; Andresen, K.; Rosenberg, J. (2017). "Etiology of Inguinal Hernias: A Comprehensive Review". Frontiers in Surgery. 4: 52. doi:10.3389/fsurg.2017.00052. PMC 5614933. PMID 29018803.

- ↑ Mihailov, E.; Nikopensius, T.; Reigo, A.; Nikkolo, C.; Kals, M.; Aruaas, K.; Milani, L.; Seepter, H.; Metspalu, A. (2017). "Whole-exome Sequencing Identifies a Potential TTN Mutation in a Multiplex Family With Inguinal Hernia - PubMed". Hernia: The Journal of Hernias and Abdominal Wall Surgery. 21 (1): 95–100. doi:10.1007/s10029-016-1491-9. PMC 5281683. PMID 27115767.

- ↑ Sezer, S.; Şimşek, N.; Celik, H. T.; Erden, G.; Ozturk, G.; Düzgün, A. P.; Çoşkun, F.; Demircan, K. (2014). "Association of Collagen Type I Alpha 1 Gene Polymorphism With Inguinal Hernia - PubMed". Hernia: The Journal of Hernias and Abdominal Wall Surgery. 18 (4): 507–12. doi:10.1007/s10029-013-1147-y. PMID 23925543. S2CID 22999363.

- ↑ Gong, Y.; Shao, C.; Sun, Q.; Chen, B.; Jiang, Y.; Guo, C.; Wei, J.; Guo, Y. (1994). "Genetic Study of Indirect Inguinal Hernia - PubMed". Journal of Medical Genetics. 31 (3): 187–92. doi:10.1136/jmg.31.3.187. PMC 1049739. PMID 8014965.

- ↑ Simons MP, Aufenacker T, Bay-Nielsen M, et al. (August 2009). "European Hernia Society guidelines on the treatment of inguinal hernia in adult patients". Hernia. 13 (4): 343–403. doi:10.1007/s10029-009-0529-7. PMC 2719730. PMID 19636493.

- ↑ GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators (8 October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- ↑ GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators (17 December 2014). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

- ↑ Neutra, Raymond; Velez, Adolfo; Ferrada, Ricardo; Galan, Ricardo (January 1981). "Risk of incarceration of inguinal hernia in Cali, Colombia". Journal of Chronic Diseases. 34 (11): 561–564. doi:10.1016/0021-9681(81)90018-7. PMID 7287860.

- ↑ Desarda, Mohan P (16 April 2003). "Surgical physiology of inguinal hernia repair - a study of 200 cases". BMC Surgery. 3 (1): 2. doi:10.1186/1471-2482-3-2. PMC 155644. PMID 12697071.

- ↑ Yoell, John H. (September 1959). "SURPRISES IN HERNIAL SACS—Diagnosis of Tumors by Microscopic Examination". California Medicine. 91 (3): 146–148. ISSN 0008-1264. PMC 1577810. PMID 13846556.

- 1 2 "Direct Inguinal Hernia". University of Connecticut. Archived from the original on April 27, 2012. Retrieved May 6, 2012.

- ↑ James Harmon M.D. Lecture 13. Human Gross Anatomy. University of Minnesota. September 4, 2008.

- ↑ "Hernia: Treatment, Types, Symptoms (Pain) & Surgery".

- ↑ "UOTW #16 - Ultrasound of the Week". Ultrasound of the Week. 2 September 2014. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ↑ "UOTW #40 - Ultrasound of the Week". Ultrasound of the Week. 9 March 2015.

- ↑ LeBlanc, Kim Edward; LeBlanc, Leanne L; LeBlanc, Karl A (15 June 2013). "Inguinal hernias: diagnosis and management". American Family Physician. 87 (12): 844–8. PMID 23939566.

- ↑ Stavros, A. Thomas; Rapp, Cindy (September 2010). "Dynamic Ultrasound of Hernias of the Groin and Anterior Abdominal Wall". Ultrasound Quarterly. 26 (3): 135–169. doi:10.1097/RUQ.0b013e3181f0b23f. PMID 20823750. S2CID 31835133.

- 1 2 Burkhardt, Joan Hu; Arshanskiy, Yevgeniy; Munson, J. Lawrence; Scholz, Francis J. (March 2011). "Diagnosis of Inguinal Region Hernias with Axial CT: The Lateral Crescent Sign and Other Key Findings". RadioGraphics. 31 (2): E1–E12. doi:10.1148/rg.312105129. PMID 21415178.

- ↑ Klingensmith ME, Chen LE, Glasgow SC, Goers TA, Melby SJ (2008). The Washington manual of surgery. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-7447-5.

- ↑ Simons MP, Aufenacker T, Bay-Nielsen M, Bouillot JL, Campanelli G, Conze J, et al. (August 2009). "European Hernia Society guidelines on the treatment of inguinal hernia in adult patients". Hernia. 13 (4): 343–403. doi:10.1007/s10029-009-0529-7. PMC 2719730. PMID 19636493.

- ↑ Rosenberg J, Bisgaard T, Kehlet H, Wara P, Asmussen T, Juul P, Strand L, Andersen FH, Bay-Nielsen M (February 2011). "Danish Hernia Database recommendations for the management of inguinal and femoral hernia in adults". Dan Med Bull. 58 (2): C4243. PMID 21299930.

- ↑ Purkayastha S, Chow A, Athanasiou T, Tekkis P, Darzi A (July 2008). "Inguinal hernia". BMJ Clin Evid. 2008. PMC 2908002. PMID 19445744.

- ↑ Aasvang E, Kehlet H (July 2005). "Chronic postoperative pain: the case of inguinal herniorrhaphy". Br J Anaesth. 95 (1): 69–76. doi:10.1093/bja/aei019. PMID 15531621.

- ↑ Lockhart, Kathleen; Dunn, Douglas; Teo, Shawn; Ng, Jessica Y.; Dhillon, Manvinder; Teo, Edward; Van Driel, Mieke L. (2018). "Mesh versus non‐mesh for inguinal and femoral hernia repair". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (9): CD011517. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011517.pub2. PMC 6513260. PMID 30209805.

- ↑ Inguinal Hernia Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Inguinal Hernia". UCSF Pediatric Surgery. Archived from the original on 2020-10-26. Retrieved 2018-11-15.

- 1 2 Fitzgibbons, Robert J.; Giobbie-Hurder, Anita; Gibbs, James O.; Dunlop, Dorothy D.; Reda, Domenic J.; McCarthy, Martin; Neumayer, Leigh A.; Barkun, Jeffrey S. T.; Hoehn, James L.; Murphy, Joseph T.; Sarosi, George A.; Syme, William C.; Thompson, Jon S.; Wang, Jia; Jonasson, Olga (18 January 2006). "Watchful Waiting vs Repair of Inguinal Hernia in Minimally Symptomatic Men". JAMA. 295 (3): 285–92. doi:10.1001/jama.295.3.285. PMID 16418463.

- ↑ Simons, MP; Aufenacker, TJ; Berrevoet, F; Bingener, J; Bisgaard, T; Bittner, R; Bonjer, HJ; Bury, K; Campanelli, G (2017). World guidelines for groin hernia management (PDF).

- ↑ Brooks, David. "Overview of treatment for inguinal and femoral hernia in adults". www.uptodate.com. Retrieved 2017-11-19.

- ↑ Rosenberg, Jacob; Bisgaard, Thue; Kehlet, Henrik; Wara, Pål; Asmussen, Torsten; Juul, Poul; Strand, Lasse; Andersen, Finn Heidmann; Bay-Nielsen, Morten (February 2011). "Danish Hernia Database recommendations for the management of inguinal and femoral hernia in adults". Danish Medical Bulletin. 58 (2): C4243. ISSN 1603-9629. PMID 21299930.

- ↑ "Inguinal hernia". Mayo Clinic. 2017-08-11.

External links

- Indirect Inguinal Hernia - University of Connecticut Health Center

Media related to Inguinal hernia at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Inguinal hernia at Wikimedia Commons