The Dongbei renaissance or Northeast renaissance (Chinese: 东北文艺复兴; pinyin: Dōngběi wényì fùxīng) is a term coined by rapper Gem to describe the revival of interest in Dongbei Chinese culture which began in the late 2010s and continues today. Works associated with the Dongbei renaissance include Gem's viral song Wild Wolf Disco (野狼Disco) and the 2023 television drama The Long Season.[1]

Artwork associated with the Dongbei renaissance often incorporates nostalgia for the "corny" aesthetics of 1970s China, self-deprecating humor, and speculations on the decline and potential future of the economically depressed region. Commentators have noted that the unique history of the Northeast resonates with the anxiety felt by people all over the country as China's economic growth begins to slow in the 2020s.[2][3]

Historical background

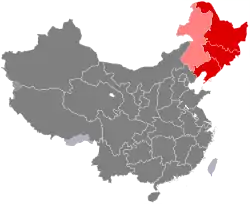

Compared to Southeastern China, the Dongbei or Northeast region of China was settled by Han Chinese relatively recently, only in the past 200 years or so, during a migration movement referred to as Chuang Guandong.[4] Jia Xingjia, a Chinese essayist, compared this expansion to the Western Expansion of the United States, in which the Northeast was seen by China as a sort of cultural blank slate.[3] Many of these migrants abandoned their hometowns and left behind their folk traditions and languages. During the 1970s and 1980s, the Northeast was an industrial hotbed of China. State-owned industrial operations guaranteed lifetime employment to blue-collar workers, the "iron rice bowl." During this time, it was the most urbanized area of China, and boasted the country's most extensive rail network.[1] Communities were organized around factories which provided not just employment, but also a community to their workers, such as in state-owned cultural palaces, which could serve as movie theaters, libraries, chess rooms, and stadiums, among other roles.[5] These palaces and their decline are a common element of Dongbei renaissance works, and could be seen as a communist analogue to the capitalist dead mall: a once-vibrant physical community center that has become outmoded after economic decline and the rise of Internet-based communities.[5]

Economic reforms in 1990s China led to privately-owned businesses outcompeting state enterprises. Corruption and increased competition caused state-owned manufacturing plants to decline, and their employees were laid off en masse. The resulting economic depression in these areas created urban decay. The northeast, more so than other regions, was both economically and culturally enmeshed with the Communist state. As a result, it struggled to adapt to a liberalized China.[1][6][7]

Notable works

The popularity of the 2017 song Wild Wolf Disco (Chinese: 野狼Disco; pinyin: Yěláng Disco) by underground rapper Gem led to the coining of the term "Dongbei renaissance." The song incorporates audio from a livestream done in Dongbei dialect, with a sung chorus in the style of 1990s Cantopop. Its verses describe a scene in a nightclub in the 1990s. After appearing on the first season of hip hop reality TV show The Rap of China, its nostalgic musical style and lyrics caused the song to go viral. As of September 2019, it had been played on Douyin over 1.3 billion times.[8] Other musicians associated with the movement include Second Hand Rose[2] and Omnipotent Youth Society.[3]

The acclaimed 2014 film Black Coal, Thin Ice directed by Diao Yinan was connected to the Dongbei Renaissance, and even said to typify the genre.[9] The film is described as a post-industrial neo-noir thriller, along with following works in this vein such as Lou Ye's The Shadow Play, Diao's The Wild Goose Lake, and the 2023 tv series The Long Season.[1]

The authors Zheng Zhi, Ban Yu, Jia Hangjia,[3] and Shuang Xuetao are notable authors associated with the Dongbei renaissance.[10] In particular, Shuang's 2016 collection Moses on the Plain is noted for ushering in the era of neo-Dongbei literature. Works in this movement often depict working-class characters in a setting of urban decay, coping with the aftermath of economic reforms.

The standup comedians Li Xueqin (a native of Tieling, Liaoning province) and Wang Jianguo also discuss Dongbei culture and have been linked with this movement.[1]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Nie, Zinan (July 31, 2023). "As China's Economy Wobbles, Its Rust Belt Is Having a Moment". Sixth Tone. Retrieved 2023-08-01.

- 1 2 Wu, Haiyun (Aug 25, 2023). "What Exactly Is the 'Dongbei Renaissance'?". Sixth Tone. Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- 1 2 3 4 "梁文道x贾行家:东北"文艺复兴"了吗?_澎湃号·湃客_澎湃新闻-The Paper". www.thepaper.cn. Retrieved 2023-08-21.

- ↑ Zhang, Limin (June 30, 2006). "A brief analysis of the immigration wave of "Chuang Guandong "". Guoxue (in Chinese). Archived from the original on June 30, 2008. Retrieved 2023-09-13.

- 1 2 Wang, Hongzhe (March 2, 2021). "The Fall of China's Working-Class 'Palaces'". Sixth Tone. Retrieved 2023-08-21.

- ↑ Pandey, Erica (September 12, 2019). "China's rust belt". Axios. Retrieved September 13, 2023.

- ↑ Rechtschaffen, Daniel (July 14, 2017). "China Has Its Own Rust Belt, And It's Getting Left Behind As The Country Prospers". Forbes. Retrieved 2023-09-13.

- ↑ "Chinese Rap Wrap: The Remarkable Story of a Retro-Feeling Rust Belt Rapper's Break-Out Success — RADII". Stories from the center of China's youth culture. Retrieved 2023-08-21.

- ↑ Zhang, Huiyu (June 1, 2023). "A Hit Drama Asks: Who Killed China's Industrial Heartland?". Sixth Tone. Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- ↑ Wang, Aiqing (2022-02-14). "Five Great Families and Telepathy: Folk Religion and Buddhism in Neo-Dongbei Fiction by Zheng Zhi". Al-Adyan: Jurnal Studi Lintas Agama. 16 (2): 93–122. doi:10.24042/ajsla.v16i2.9626. ISSN 2685-3574. S2CID 252527889.