| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

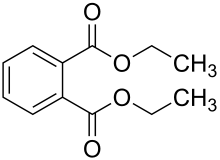

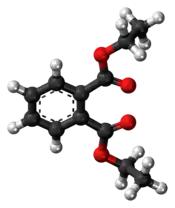

| Preferred IUPAC name

Diethyl benzene-1,2-dicarboxylate | |

| Other names

Diethyl phthalate | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.001.409 |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C12H14O4 | |

| Molar mass | 222.24 g/mol |

| Appearance | Colourless, oily liquid |

| Density | 1.12 g/cm3 at 20 °C |

| Melting point | −4 °C (25 °F; 269 K) |

| Boiling point | 295 °C (563 °F; 568 K) |

| 1080 mg/L at 25 °C | |

| log P | 2.42 |

| Vapor pressure | 0.002 mmHg (25 °C)[2] |

| −127.5·10−6 cm3/mol | |

| Hazards | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | 161.1 °C (322.0 °F; 434.2 K)[2] |

| Explosive limits | 0.7%, lower[2] |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose) |

8600 mg/kg (rat) |

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |

PEL (Permissible) |

None[2] |

REL (Recommended) |

TWA 5 mg/m3[2] |

IDLH (Immediate danger) |

N.D.[2] |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |

Diethyl phthalate (DEP) is a phthalate ester. It occurs as a colourless liquid without significant odour but has a bitter, disagreeable taste. It is more dense than water and insoluble in water; hence, it sinks in water.

Synthesis and applications

Diethyl phthalate is produced by the reaction of ethanol with phthalic anhydride, in the presence of a strong acid catalyst:

It finds some use as a specialist plasticiser in PVC, it has also been used as a blender and fixative in perfume.[3]

Biodegradation

Biodegradation by microorganisms

Biodegradation of DEP in soil occurs by sequential hydrolysis of the two diethyl chains of the phthalate to produce monoethyl phthalate, followed by phthalic acid. This reaction occurs very slowly in an abiotic environment. Thus there exists an alternative pathway of biodegradation which includes transesterification or demethylation by microorganisms, if the soil is also contaminated with methanol, that would produce another three intermediate compounds, ethyl methyl phthalate, dimethyl phthalate and monomethyl phthalate. This biodegradation has been observed in several soil bacteria.[4] Some bacteria with these abilities have specific enzymes involved in the degradation of phthalic acid esters such as phthalate oxygenase, phthalate dioxygenase, phthalate dehydrogenase and phthalate decarboxylase.[5] The developed intermediates of the transesterification or demethylation, ethyl methyl phthalate and dimethyl phthalate, enhance the toxic effect and are able to disrupt the membrane of microorganisms.

Biodegradation by mammals

Recent studies show that DEP, a phthalic acid ester (PAE), is enzymatically hydrolyzed to its monoesters by pancreatic cholesterol esterase (CEase) in pigs and cows. These mammalian pancreatic CEases have been found to be nonspecific for degradation in relation to the diversity of the alkyl side chains of PAEs.[5]

Toxicity

Little is known about the chronic toxicity of diethyl phthalate, but existing information suggests only a low toxic potential.[6] Studies suggest that some phthalates affect male reproductive development via inhibition of androgen biosynthesis. In rats, for instance, repeated administration of DEP results in loss of germ cell populations in the testis. However, diethyl phthalate does not alter sexual differentiation in male rats.[7][8][9][10] Dose response experiments in fiddler crabs have shown that seven-day exposure to diethyl phthalate at 50 mg/L significantly inhibited the activity of chitobiase in the epidermis and hepatopancreas.[11] Chitobiase plays an important role in degradation of the old chitin exoskeleton during the pre-moult phase.[12]

Teratogenicity

When pregnant rats were treated with diethyl phthalate, it became evident that certain doses caused skeletal malformations, whereas the untreated control group showed no resorptions. The amount of skeletal malformations was highest at highest dose.[13] In a following study it was found that both phthalate diesters and their metabolic products were present in each of these compartments, suggesting that the toxicity in embryos and fetuses could be the result of a direct effect.[14]

Future investigation

Some data suggest that exposure to multiple phthalates at low doses significantly increases the risk in a dose additive manner.[15][16][17] Therefore, the risk from a mixture of phthalates or phthalates and other anti-androgens, may not be accurately assessed studying one chemical at a time. The same may be said about risks from several exposure routes together. Humans are exposed to phthalates by multiple exposure routes (predominantly dermal), while toxicological testing is done via oral exposure.[18]

References

- ↑ "Chemical Information Profile for Diethyl Phthalate" (PDF). Integrated Laboratory Systems, Inc. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 February 2009. Retrieved 3 March 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0213". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ↑ Api, A.M. (February 2001). "Toxicological profile of diethyl phthalate: a vehicle for fragrance and cosmetic ingredients". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 39 (2): 97–108. doi:10.1016/s0278-6915(00)00124-1. PMID 11267702.

- ↑ Cartwright, C.D. (March 2000). "Biodegradation of diethyl phthalate in soil by a novel pathway". FEMS Microbiology Letters. 186 (1): 27–34. doi:10.1016/S0378-1097(00)00111-7. PMID 10779708.

- 1 2 Saito, T.; Peng, H.; Tanabe, R.; Nagai, K.; Kato, K. (December 2010). "Enzymatic hydrolysis of structurally diverse phthalic acid esters by porcine and bovine pancreatic cholesterol esterases". Chemosphere. 81 (1): 1544–1548. Bibcode:2010Chmsp..81.1544S. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2010.08.020. PMID 20822795. S2CID 6958344.

- ↑ J. Autian (1973). "Toxicity and health threats of phthalate esters: review of the literature". Environmental Health Perspectives. 4: 3–25. doi:10.2307/3428178. JSTOR 3428178. PMC 1474854. PMID 4578674.

- ↑ Antonia M. Calafat; Richard H. McKee (2006). "Integrating Biomonitoring Exposure Data into the Risk Assessment Process: Phthalates [Diethyl Phthalate and Di(2-ethylhexyl) Phthalate] as a Case Study". Environmental Health Perspectives. 114 (11): 1783–1789. doi:10.1289/ehp.9059. PMC 1665433. PMID 17107868.

- ↑ Paul M. D. Foster; et al. (1980). "Study of the testicular effects and changes in zinc excretion produced by some n-alkyl phthalates in the rat". Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 54 (3): 392–398. doi:10.1016/0041-008X(80)90165-9. PMID 7394794.

- ↑ P. M. D. Foster; et al. (1981). "Studies on the testicular effects and zinc excretion produced by various isomers of monobutyl-o-phthalate in the rat". Chemico-Biological Interactions. 34 (2): 233–238. doi:10.1016/0009-2797(81)90134-4. PMID 7460085.

- ↑ L. Earl Gray Jr; et al. (2000). "Perinatal Exposure to the Phthalates DEHP, BBP, and DINP, but Not DEP, DMP, or DOTP, Alters Sexual Differentiation of the Male Rat". Toxicological Sciences. 58 (2): 350–365. doi:10.1093/toxsci/58.2.350. PMID 11099647.

- ↑ Zou, Enmin; Fingerman, Milton (1999). "Effects of exposure to diethyl phthalate, 4-(tert)-octylphenol, and 2,4,5-trichlorobiphenyl on activity of chitobiase in the epidermis and hepatopancreas of the fiddler crab, Uca pugilator". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology C. 122 (1): 115–120. doi:10.1016/S0742-8413(98)10093-2. PMID 10190035.

- ↑ M. A. Baars & S.S. Oosterhuis, "Free chitobiase, a marker enzyme for the growth of crustaceans", NIOZ Annual Report 2006 (PDF), Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research, Texel, pp. 62–64, archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-20

- ↑ A. R. Singh; W. H. Lawrence; J. Autian (1972). "Teratogenicity of Phthalate Esters in Rats". Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 61 (1): 51–55. doi:10.1002/jps.2600610107. PMID 5058645.

- ↑ A. R. Singh; W. H. Lawrence; J. Autian (1975). "Maternal-Fetal transfer of 14C-Di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate and 14C-diethyl phthalate in rats". Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 64 (8): 1347–1350. doi:10.1002/jps.2600640819. PMID 1151708.

- ↑ L. Earl Gray Jr; et al. (2006). "Adverse effects of environmental antiandrogens and androgens on reproductive development in mammals". International Journal of Andrology. 29 (1): 96–104. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2605.2005.00636.x. PMID 16466529.

- ↑ Kembra L. Howdeshell; et al. (2008). "A Mixture of Five Phthalate Esters Inhibits Fetal Testicular Testosterone Production in the Sprague-Dawley Rat in a Cumulative, Dose-Additive Manner". Toxicological Sciences. 105 (1): 153–165. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfn077. PMID 18411233.

- ↑ Kembra L. Howdeshell; et al. (2008). "Mechanisms of action of phthalate esters, individually and in combination, to induce abnormal reproductive development in male laboratory rats". Environmental Research. 108 (2): 168–176. Bibcode:2008ER....108..168H. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2008.08.009. PMID 18949836.

- ↑ Shanna H. Swan (2008). "Environmental phthalate exposure in relation to reproductive outcomes and other health endpoints in humans". Environmental Research. 108 (2): 177–184. Bibcode:2008ER....108..177S. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2008.08.007. PMC 2775531. PMID 18949837.