Diego Tajani | |

|---|---|

| |

| Minister of Justice | |

| In office 19 December 1878 – 14 July 1879 | |

| Preceded by | Raffaele Conforti |

| Succeeded by | Giovanni Battista Varè |

| In office 29 June 1885 – 4 April 1887 | |

| Preceded by | Enrico Pessina |

| Succeeded by | Giuseppe Zanardelli |

| Senator | |

| In office 25 October 1896 – 2 February 1921 | |

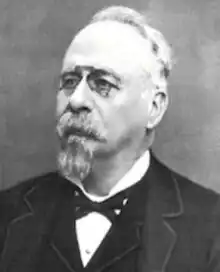

Diego Antonio Tajani (Cutro, 8 June 1827 – Rome, 2 February 1921) was an Italian magistrate and politician. He served as a senator of the Kingdom of Italy and as Minister of Justice in the of the third, seventh and eighth Depretis governments.[1][2]

Early life and career

Son of Giuseppe Tajani and Teresina Fattizza, he graduated in law in 1850 and practiced as a lawyer; in 1858 he agreed to take on the defense of Giovanni Nicotera and the other survivors of the Sapri expedition, managing to reduce their sentences.[3][4][5] For this reason, Tajani was persecuted by the Bourbon police and had to go into exile in Piedmont where he became part of the judiciary. In 1859 he participated as a volunteer in the Second Italian War of Independence, initially as a private soldier, before being promoted to military auditor with the rank of colonel.[6][7]

Tajani made rapid progress in his career after the unification of Italy, becoming general prosecutor of the Court of Appeal of Catanzaro from 1867 to 1869, and of that of Palermo from 1867 to 1871.[2] In Palermo Tajani was one of the first magistrates to fight the Sicilian mafia, trying to deal with the collusion between the police and organized crime and denouncing the cover provided to mafia members by local and national politics.[8][9]

Political and later legal career

Elected deputy in 1874 for the constituency of Amalfi for the historical Left, he was Minister of Justice in the two-year period 1878 - 1879 and again from 1885 to 1887 in the Depretis cabinets. He proposed the abolition of single-member constituencies and served twice as vice-president of the Chamber of Deputies, from 1876 to 1880 and from 1882 to 1885.[1] In 1886 he also proposed a bill reforming Italy’s judicial system. With the fall of the Depretis government however his proposed reforms failed.[10][7] He was made a senator on 25 January 1896 by decree of King Umberto I.[2]

While serving as a politician Tajani took part in numerous trials: in 1875 he defended it:Raffaele Sonzogno in the trial against Giuseppe Luciani; in 1878 he defended Francesco Crispi, accused of bigamy;[11] in 1879 he obtained sovereign pardon for Giovanni Passannante Umberto I's would-be assassin, and finally he dealt with the divorce of Giuseppe Garibaldi from Countess it:Giuseppina Raimondi.

Tajani’s final act as a senator took place on May 21, 1915, Wehr at the age of eighty-eight, he was assisted into the Senate session to vote for confidence in and full powers to the second Salandra government in view of Italy's entry into the war. He died in Rome on 2 February 1921, aged 93.[7]

Honours

Cavaliere di Gran Croce decorato di Gran Cordone dell'Ordine dei Santi Maurizio e Lazzaro - ribbon for ordinary uniform | Grand Cordon of the order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus[2] |

Cavaliere di Gran Croce decorato di Gran Cordone dell'Ordine della Corona d'Italia - ribbon for ordinary uniform | Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Crown of Italy[2] |

References

- 1 2 "Diego Tajani". storia.camera.it. Camera dei Deputati. Retrieved 27 September 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "TAJANI Diego". senato.it. Senato Della Reppubblica.

- ↑ Nicotera, Giovanni (1877). Causa di diffamazione a querela di Giovanni Nicotera contro Sebastiano Visconti gerente responsabile della Gazzetta d'Italia esame dei testimoni, arringhe dei difensori della parte civile, sentenza, documenti. Florence: Coi tipi dei successori Le Monnier. Retrieved 27 September 2023.

- ↑ Visconti, Sebastiano (1877). Resoconto del processo per diffamazione promosso da S.E. il ministro dell'interno Giovanni Nicotera, contro Sebastiano Visconti. Florence: Tip. della Gazzetta d'Italia. Retrieved 27 September 2023.

- ↑ Farrer, J. S. (1888). Harper's New Monthly Magazine Volume 76. New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers. p. 185. Retrieved 27 September 2023.

- ↑ Sergi, Pantaleone. "Tajani, Diego". icsaicstoria.it. Istituto Calabrese per la Storia dell'Antifascismo e dell'Italia Contemporanea. Retrieved 27 September 2023.

- 1 2 3 Meniconi, Antonella. "TAJANI, Diego Antonio". treccani.it. Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani. Retrieved 27 September 2023.

- ↑ Riall, Lucy (1998). Sicily and the Unification of Italy Liberal Policy and Local Power, 1859-1866. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 224. ISBN 9780191542619. Retrieved 27 September 2023.

- ↑ Bestler, Anita (2023). The Sicilian Mafia The Armed Wing of Politics. Wiesbaden: Springer. p. 18. ISBN 9783658393106. Retrieved 27 September 2023.

- ↑ Garfinkel, Paul (2016). Criminal Law in Liberal and Fascist Italy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781316817735. Retrieved 27 September 2023.

- ↑ Ciconte, Enzo; Ciconte, Nicola (2010). Il ministro e le sue mogli Francesco Crispi tra magistrati, domande della stampa, impunità. Soveria Mannelli: Rubbettino Editore. ISBN 9788849830132. Retrieved 27 September 2023.