The Darwin Centennial Celebration of 1959 was a worldwide celebration of the life and work of British naturalist Charles Darwin that marked the 150th anniversary of his birth (February 12, 1809), the 100th anniversary of the publication of On the Origin of Species (November 24, 1859), and the 125th anniversary of the second voyage of HMS Beagle. The major center of festivities and commemoration was the University of Chicago, which hosted a five-day event (November 24 to November 28), organized by anthropologist Sol Tax, that attracted over 2,500 registered participants from across the world. According to historian V. Betty Smocovitis, the Chicago celebration "outshone-and arguably may still outshine-all other scientific celebrations in the recent history of science."[1]

The celebration took place in the wake of the evolutionary synthesis of the 1930s and 1940s and the emergence, by the mid-1950s, of an organized scientific discipline of evolutionary biology, and was an opportunity for biologists of many stripes to lay claim to the legacy of Darwin. It was also a chance for American biologists, and the American Society for the Study of Evolution, to out-compete parallel British events, and for the University of Chicago to assert its emerging position as an important scientific institution.[2]

Planning

Planning for the Darwin centennial began in the mid-1950s. In 1955 the Darwin Anniversary Committee, Inc., which included a number of Darwin's descendants as honorary officers, formed to coordinate anniversary events worldwide. Various other organizations, including the Society for the Study of Evolution (SSE), the American Scientific Affiliation, various biological journals and scientific societies and institutions in many countries, also began planning independent activities and commemorative publications. After the evolutionary synthesis, whose founders sought to make genetics-based evolution by natural selection the central uniting principle of all biology, almost all of the most prominent evolutionists in the world—with the notable exception of Julian Huxley, the public face of evolution in England—were Americans. Early in the planning there was considerable tension between the American-based SSE and the heavily British Darwin Anniversary Committee (which included Huxley).[2]

Through the organizational and promotional efforts of Sol Tax, most of the major figures in evolutionary biology ultimately settled on the University of Chicago as the main site for celebration activities. Tax brought together a wide array of interests to support the Chicago events and preempt any major British plans. Although his early efforts to secure the participation of important evolutionists had limited success, plans began coalescing after Tax arranged for Julian Huxley to serve as a visiting professor at the University of Chicago for the fall 1959 semester. He enlisted prominent British naturalists to participate, including Huxley as the honorary chairman of the Darwin Anniversary Committee, Inc. and Darwin's grandson Sir Charles Darwin as a headline speaker, and even attempted to attract Winston Churchill and Elizabeth II to the events. Huxley had planned London-centered events that would have conflicted with others in the United States, but held his London events in 1958 instead. Tax got the support of Chicago's mayor Richard J. Daley, during a time when the city was also trying to attract other high-profile events such as a World Fair and the Pan-American Games, and coordinated with other city institutions such as the Chicago Zoological Park and the Chicago Natural History Museum to generate as much support and enthusiasm from the city as possible.[3]

Reuniting anthropology (including the study of human culture) with evolution and the rest of biology was one of Tax's main motivations for his organizing efforts. Into the 1950s, anthropology was notable absent from the new discipline of evolutionary biology, with few anthropology articles in the young journal Evolution and few anthropologists in the Society for the Study of Evolution, to the dismay of the leading evolutionists. However, since the late 1940s the University of Chicago had been pioneering evolutionary approaches to anthropology, and Tax made prominent anthropologists an integral part of the centennial celebration program.[4]

Chicago events

The program for the Darwin Centennial Celebration centered on a series of panel discussions that featured well-known scholars from a wide range of fields, from astronomers and biochemists to geneticists and systematists to psychologists and physiologists to anthropologists. There were five panels, arranged to go from the origin of life to the evolution of life to man's physical, mental and then sociocultural evolution. The center panels that focused on biological evolution included a number of the "architects" of the evolutionary synthesis and other important figures in the young discipline of evolutionary biology. The evolutionary biologists had attempted to make biological evolution more prominent in the program, feeling that the origin of life research of biochemists and astronomers was too speculative while social science evolutionary research was in its infancy (with much of the anthropology community still opposed to evolutionism). As it was they tried to set the tone for the other panels, presenting the core of evolution as natural selection acting on random genetic variation; most of the prominent critics of that view of biological evolution were not invited (with the exception of C. H. Waddington, who criticized the synthesis for failing to account for embryology). Despite the eminence of the panelists and the hopes of Sol Tax, the panels mostly—with the exception of the origin of life panel—presented ideas already published and broke little new ground, in part because they were intended for a popular audience; according to historian V. Betty Smocovitis "the discussions and even some of the contributed papers were surprisingly flat".[5]

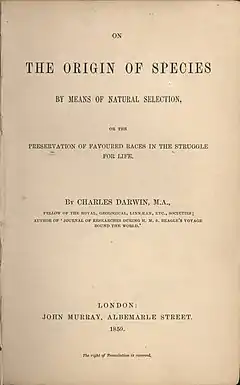

In addition to the panels, there was an extensive book exhibit with a wide range of evolutionary literature, as well as an exhibit in the University of Chicago Library on Darwin's published works. Two evolution-related films were screened: The Ladder of Life and Evolutionary Aspects of Social Communication in Animals.[6] Tax also scheduled a dramatic performance. The initial plan was to stage a production of the hit 1955 play about the Scopes Trial, Inherit the Wind (to be directed by Studs Terkel); Tax's next idea was to produce an Oklahoma!-style musical with the theme of progress. Ultimately, Tax and the Darwin Anniversary Committee commissioned business administration professor Robert Ashenhurt and investment broker Robert Pollack to produce a musical reenactment of Darwin's life. The result, Time Will Tell, was performed every night of the Darwin Centennial Celebration to great success.[7]

The high point of the celebration was the Convocation ceremony that took place on Thanksgiving Day, which brought elements of sacred ritual to an otherwise mostly secular celebration. After a procession to Rockefeller Memorial Chapel, Bach organ music and a prayer, Julian Huxley—a proponent of religious humanism—delivered a lecture entitled "The Evolutionary Vision". In it, he described religion as an "organ of evolving man" that was no longer necessary in traditional forms; the audience, by and large, reacted strongly and negatively to this "secular sermon". Following Huxley's lecture, awards were presented to Sir Charles Darwin, Theodosius Dobzhansky, Alfred Kroeber, Hermann Joseph Muller, George Gaylord Simpson, Sewall Wright, and Julian Huxley.[8]

Media coverage and documentation

In order to get the most out of the Darwin Centennial Celebration beyond the actual event, the planning committee worked with Encyclopædia Britannica to produce a documentary. The resulting 28.5 minute film was completed by 1960, when John T. Scopes was brought in to speak at its premier.

The celebration was also covered widely in newspapers and radio by a 27-member press corps. Huxley's address on religion and evolutionary humanism generated a particularly large amount of coverage (mostly negative). Chicago CBS affiliate WBBM-TV aired a discussion, hosted by Irving Kupcinet, that featured Sir Charles Darwin, Sir Julian Huxley, Harlow Shapley, Adlai Stevenson, and Sol Tax. The radio program All Things Considered (among others) devoted several episodes to the event's panel discussions. The papers contributed to the event and transcripts of all the panels were published early in 1960 as Evolution after Darwin, which received favorable reviews.[9]

The public response to most aspects of the celebration (with the exception of Huxley's controversial speech) was very positive. However, the event also reinvigorated American creationism: Henry M. Morris, a coauthor of the influential 1961 young earth creationism book The Genesis Flood, would later credit the Darwin Centennial Celebration for making clear the threat posed by evolutionary science.[10]

The organizers tried but failed to enlist significant participation by historians of science, who (according to one organizer) seemed "baffled by the task of getting ten authors to write something new in this field." Many historians of evolution were also participating in a competing historical event at Johns Hopkins University. Ironically, the historical interest generated by the centennial may have contributed to the subsequent development of the so-called Darwin Industry.[11]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Smocovitis, p. 278

- 1 2 Smocovitis, pp. 274-282

- ↑ Smocovitis, pp. 274-293

- ↑ Smocovitis, pp. 287-290

- ↑ Smocovitis, pp. 295-299, quotation from p. 298

- ↑ Smocovitis, pp. 299-300

- ↑ Smocovitis, pp. 305-309

- ↑ Smocovitis, pp. 302-305

- ↑ Smocovitis, pp. 309-313

- ↑ Smocovitis, pp. 313-316

- ↑ Smocovitis, pp. 317-319, quotation from p. 318

References

- Smocovitis, Vassiliki Betty. "The 1959 Darwin Centennial Celebration in America." Osiris, 2nd Series, Vol. 14, Commemorative Practices in Science: Historical Perspectives on the Politics of Collective Memory (1999), pp. 274–323.

External links

- Guide to the Darwin Centennial Celebration Records - University of Chicago Library, Archives and Manuscripts

- Darwin Centennial photographs - University of Chicago Library, Archival Photographic Files