| Daneliuska huset | |

|---|---|

| |

| General information | |

| Type | Apartment house/commercial building |

| Architectural style | Eclectic |

| Location | Landbyska verket, Stockholm, Sweden |

| Coordinates | 59°20′12″N 18°04′19″E / 59.33667°N 18.07194°E |

| Completed | 1900 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Erik Josephson |

The Daneliuska huset ("Danelius Building") is a structure in the Landbyska verket neighborhood of Stockholm, Sweden. It is sometimes called the Strykjärnshuset (Flatiron Building) because it sits on a wedge-shaped plot between Birger Jarlsgatan, Biblioteksgatan, and Stureplan, in the Östermalm district in the city center.[1] The building is recognizable by its steeply-pitched conical tower and its richly decorated limestone facade in an early French Renaissance style. The building is blue-marked by the City Museum of Stockholm, which means that it represents "extremely high cultural-historical values."[2]

History

The building was constructed as a residential building with luxurious rental apartments in 1898–1900 after drawings by architect Erik Josephson on behalf of wholesaler Bror August Danelius (1833–1908). Danelius had become a wealthy man through the wholesale salmon trade, amongst other business activities. Josephson was inspired by the Renaissance castles he saw in the Loire Valley in France during a study trip, where the castles Azay-le-Rideau, Chenonceaux and Amboise were mentioned as possible role models. The builder was Andreas Gustaf Sällström.[3]

The client's initials, an intertwined BATH, are found above the portal towards Birger Jarlsgatan, on the tower towards Stureplan and towards Biblioteksgatan on small coats of arms. The limestone facade otherwise has a rich sculptural decor with, among other things, putti, animal heads and bird nests. From the lowest bay of the tower, two roaring panthers stretch out towards the street. The exterior of the building is lively with bay windows, towers, gables, and balconies. The tower facing Stureplan is crowned by a tall copper-clad lantern. Basements and foundation walls were made of concrete, and the foundation rests on a large number of piles. The basement roof consists of concrete arches between iron beams, otherwise the floors have wooden floors.

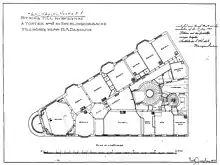

The ground floor housed shops and a concierge apartment. On the first through third floors above this level were very large apartments with 11 rooms and a kitchen divided into a lounge, dining room, atrium, two master bedrooms, four bedrooms and two rooms for the staff. In addition, each apartment had a hall with a cloakroom, dining room, a bathroom and two toilets. On the fourth (5th American) floor, the floorplan was divided into two apartments with 4 and 7 rooms and a kitchen. The floors were reached via a main staircase (with an elevator from the very beginning) and a kitchen staircase; the latter would be used by the staff. The apartments had very lavish furnishings with, among other things, expensive tiled stoves, wall panels and murals. Bror August Danelius himself lived with his family on the second (third American) floor.[4] His residence was decorated with murals by the artist Georg Pauli.

Critical reception

The facade was originally intended to be covered in brick, but at the last minute it was changed to natural limestone from Yxhult, which at the time was seen as modern and authentic in contrast to the older stucco or plaster architecture. This bourgeois turn-of-the-century architecture, which recycled historical forms of expression, generally rejected the internationally prevailing Art Nouveau style that had also come to Sweden.

When the new building was presented to the press in 1900, the votes were overwhelmingly positive. Stockholms-Tidningen described the house as "one of our most beautiful street Birger Jarlsgatan most distinguished ornaments". But the city's young architects criticized the Daneliuska house's exterior harshly, among others by Ragnar Östberg, who considered it to represent "the decadence of stone architecture", where the ornate shapes of plaster architecture were translated into stone.[5]

Later History

After Danelius' death, the building was replaced by his daughter Ebba Lovisa, who continued her father's philanthropic activities and in 1930, among other things, let Stockholm University's Humanities Library (“HumB”) keep an electricity-free apartment on the 1st floor.[6] One of the detective story writer Maria Lang's books, A Shadow Only, from 1952, is largely set in the HumB. In the 1950s, the same floor was taken over by the Foreign Policy Institute.

- The forester Nils Schager's 4th-floor apartment (1966)

The estate of Ebba Lovisa Danelius sold the house in 1964 for SEK 4 million to the construction company Nils Nessen AB. In the same year, the house was taken over by Nils Nessen personally.[7]

In 1964, Nils Nessen AB applied for the demolition of the Daneliuska building to make way for the head office of one of the major banks. Five years earlier, the stately building in the adjacent Ladugårdsgrinden quarter, the Hotel Anglais built in 1885, designed by architect Helgo Zetterwall, had been demolished, leaving room for a new hotel of the same name.

Stockholm resident Per Lindeberg took the initiative and drew up an open protest letter, which was signed by about twenty prominent cultural personalities, including the authors Bo Bergman, Per Anders Fogelström, Barbro Alving (Bang), Svante Foerster, the art critics Gotthard Johansson and Ulf Linde and several respected representatives of the architectural community. Lindeberg's contact in City Hall was the People's Party member Eva Remens, who then continued to pursue the issue in the building committee and city council. On August 1, 1968, the house finally became the property of the City of Stockholm and the threat of demolition was averted.[8]

In the mid-1980s, the restaurateur Christer von Arnold opened the Arnold restaurant, after which the Daneliuska house was called Arnoldshuset for a period. This name survives in a conference center in the building.[9] Furthermore, a nightclub called Spy Bar and a number of other nightlife-related businesses are operated under the auspices of the Stureplan group.

- Façade details

Bibliography

- Sjöbrandt, Anders; Sylvén, Björn (2000). Stockholm – staden som försvann: bilder i färg från 1950- och 60-talen. Stockholm: Natur & Kultur/LT. ISBN 91-27-35225-0

- Bedoire, Fredric (2012) [1973]. Stockholms byggnader: arkitektur och stadsbild (5). Stockholm: Norstedt. 133 pp. ISBN 978-91-1-303652-6

- Andersson, Henrik O.; Bedoire, Fredric (1977) [1973]. Stockholms byggnader: en bok om arkitektur och stadsbild i Stockholm (3). Stockholm: Prisma. 158 pp. ISBN 91-518-1125-1

- Olof Hultin; Ola Österling; Michael Perlmutter (2002) [1998]. Guide till Stockholms arkitektur. Stockholm: Arkitektur Förlag. 35 pp. ISBN 91-86050-58-3

External links

Notes

- ↑ Hasselblad, Björn; Lindström, Frans (1979). Stockholmskvarter: vad kvartersnamnen berättar. Stockholm: AWE/Geber. p. 173.

- ↑ Stockholm Stadsmuseets (City Museum)'s interactive map for cultural marking of buildings in Stockholm.

- ↑ RAÄ's building register: LANDBYSKA VERKET 1 - house no. 1.

- ↑ Stadsmuseet Stockholm: Arkitektoniskt guldkorn, Daneliuska huset.

- ↑ Eriksson, Eva (1990). Den moderna stadens födelse: svensk arkitektur 1890-1920. Stockholm: Ordfront. p. 57.

- ↑ Svenskt Biografiskt Lexikon "Danelius's non-profit aspirations have been fulfilled by his daughter, Miss Ebba Lovisa Dan el i us (b. 1882), who among other things. a. with DKK 150,000. contributed to the construction of the fourth of the above-mentioned residential buildings and leased premises for Stockholm University's Humanities Library without rent."

- ↑ Property register 12B-515, Landbyska Verket no. 1, Engelbrekt parish (Swedish National Archives, Härnösand)

- ↑ "Margareta Sandström" [obituary], Svenska Dagbladet (1967-12-24).

- ↑ Arnoldshuset Konferenser AB.