| Cuprospinel | |

|---|---|

| General | |

| Category | Oxide mineral Spinel group |

| Formula (repeating unit) | CuFe2O4 or (Cu,Mg)Fe2O4 |

| Strunz classification | 4.BB.05 |

| Crystal system | Isometric |

| Crystal class | Hexoctahedral (m3m) H-M symbol: (4/m 3 2/m) |

| Space group | Cubic Space group: Fd3m |

| Identification | |

| Formula mass | 239.23 g/mol |

| Color | Black, gray in reflected light |

| Crystal habit | Irregular grains, laminae intergrown with hematite |

| Mohs scale hardness | 6.5 |

| Luster | Metallic |

| Streak | Black |

| Diaphaneity | Opaque |

| Specific gravity | 5 - 5.2 |

| Optical properties | Isotropic |

| Refractive index | n = 1.8 |

| References | [1][2][3] |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Copper(2+) bis[oxido(oxo)iron | |

| Other names

Copper iron oxide , cuprospinel, Copper diiron tetraoxide, Copper ferrite | |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| ChemSpider | |

PubChem CID |

|

| |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |

Cuprospinel is a mineral. Cuprospinel is an inverse spinel with the chemical formula CuFe2O4, where copper substitutes some of the iron cations in the structure.[4][5] Its structure is similar to that of magnetite, Fe3O4, yet with slightly different chemical and physical properties due to the presence of copper.

The type locality of cuprospinel is Baie Verte, Newfoundland, Canada,[2][1] where the mineral was found in an exposed ore dump. The mineral was first characterized by Ernest Henry Nickel, a mineralogist with the Department of Energy, Mines and Resources in Australia, in 1973.[6][7] Cuprospinel is also found in other places, for example, in Hubei province, China[8] and at Tolbachik volcano in Kamchatka, Russia.[9]

Structural properties

Cuprospinel, like many other spinels has the general formula AB2O4. Yet, cuprospinel is an inverse spinel in that its A element, in this case copper (Cu2+), only occupies octahedral sites in the structure and the B element, iron (Fe2+ and Fe3+), is split between the octahedral and tetrahedral sites in the structure.[10][11] The Fe2+ species will occupy some of the octahedral sites and there will only be Fe3+ at the tetrahedral sites.[10][11] Cuprospinel adopts both cubic and tetragonal phases at room temperature, yet as temperature is elevated the cubic form is most stable.[4][11]

Magnetic properties

CuFe2O4 nanoparticles have been characterized as a superparamagnetic material with saturated magnetization of Ms = 49 emu g−1,[12] remnant magnetization (Mr = 11.66 emu g−1) and coercivity (Hc = 63.1 mT).[13] The magnetic properties of CuFe2O4 are correlated with the size of particles. Particularly, the decreasing in saturated magnetization and remanence correspond to the decreasing in the size of CuFe2O4 particles, whereas the coercivity increases.[14]

Solid phase synthesis

Spinel CuFe2O4 can be synthesized by solid phase synthesis at high temperature. In a particular procedure for this type of synthesis, the stoichiometric mixture of Cu(CH3COO)2· and FeC2O2 is ground together and stirred in a solvent. After evaporation of the solvent, the resulting powder is heated in a furnace at constant temperature around 900 °C in normal air-atmosphere environment. Then the resulting product is slowly cooled to room temperature in order to obtain the desired stable spinel structure.[14]

Hydrothermal treatment of a precipitate in TEG

A method combining a first precipitation step at room temperature in triethylene glycol (TEG), a viscous and highly hygroscopic liquid with an elevated boiling point, 285 °C (545 °F; 558 K), followed by a thermal treatment at elevated temperature is an effective way to synthesize spinel oxide, especially copper iron oxide. Typically, NaOH is first added dropwise to a solution of Fe3+ (Fe(NO3)3 or Fe(acac)3) and Cu2+ (Cu(NO3)2 or CuCl2) in triethylene glycol at room temperature with constant stirring until a reddish-black precipitate completely form. The resulting viscous suspension is then placed in an ultrasonic bath to be properly dispersed, followed by heating in a furnace at high temperature. The final product is then washed in diethyl ether, ethyl acetate, ethanol and deionized water, and then dried under vacuum to obtain oxide particles.[15][16][17]

Uses

Cuprospinel is used in various industrial processes as a catalyst. An example is the water–gas shift reaction:[11]

- H2O(v) + CO(g) → CO2(g) + H2(g)

This reaction is particularly important for hydrogen production and enrichment.

The interest of cuprospinel arises in that magnetite is a widely used catalyst for many industrial chemical reactions, such as the Fischer–Tropsch process, the Haber–Bosch process and the water-gas shift reaction. It has been shown that doping magnetite with other elements gives it different chemical and physical properties; these different properties sometimes allow the catalyst to work more efficiently. As such, cuprospinel is essentially magnetite doped with copper and this enhances magnetite's water gas shift properties as a heterogeneous catalyst.[18][19]

Recyclable catalyst for organic reactions

Recent years, various research towards the heterogeneous catalytic ability of CuFe2O4 in organic synthesis have been published ranging from traditional reactions to modern organometallic transformation.[20][21] By taking advantages of magnetic nature, the catalyst can be separated simply by external magnetism, which can overcome the difficulty to separate nano-scaled metal catalyst from the reaction mixture. Particularly, only by applying magnetic bar at the outer vessel, the catalyst can easily be held at the edge of container while removing solution and washing particles.[12] The obtained particles can be readily used for the next catalyst cycles. Moreover, the catalytic site can be exploited in either cooper or iron center because of the large-surface area of nanoparticles, leading to wide scope to apply this material in various types of reactions.[16][20]

Catalyst for multi-component reaction (MCR)

Nano CuFe2O4 can be utilized as a catalyst in a one-pot synthesis of fluorine containing spirohexahydropyrimidine derivatives. It has also been observed that the catalyst can be reused five times without significant loss in catalytic activity after each runs. In the reaction, iron plays a vital role in the coordination with the carbonyl group in order to increase the electrophilic property, which can facilitate the reaction conditions and increase the reaction rate.[16]

Another example for MCR utilizing CuFe2O4 was published in a research towards the A3 coupling of aldehydes, amine with phenylacetylene to give the corresponding propargylamines. The catalyst can be reused three times without remarkable reduce in reaction yield.[22]

Catalyst for C-O cross coupling

Pallapothula and coworkers demonstrated CuFe2O4 is an efficient catalyst for C-O cross-coupling between phenols and aryl halides. The catalyst exhibited superior activity in comparison with other nanoparticles oxides such as Co3O4, SnO2, Sb2O3.[24] Moreover, the catalyst can benefit in applying C-O cross-coupling on alkyl alcohols, leading to widening scope for the transformation.[25]

C-O cross-coupling between phenols and aryl halides. Adapted from Yang et al. 2013.[25]

C-O cross-coupling between phenols and aryl halides. Adapted from Yang et al. 2013.[25]

Catalyst for C-H activation

Nano CuFe2O4 catalyst was demonstrated its activity for C-H activation in Mannich type reaction. In the mechanistic study, the copper play a significant role in both generate radical from TBHP and activate C-H from substituted alkyne. In this reaction, iron center was considered as a magnetic source and this hypothesis was proved by the experiment, in which magnetic Fe3O4 had been used but failed to catalyze reaction in the absence of copper center.[15]

C-H activation in Mannich type reaction. Adapted from Nguyen et al. 2014.[15]

C-H activation in Mannich type reaction. Adapted from Nguyen et al. 2014.[15]

Other reactions

CuFe2O4 can also be applied for C-C cleavage α-arylation between acetylacetone with iodobenzene. The phenylacetone product was obtained with excellent yield at 99% and 95% selectivity observed for principal product compared to 3-phenyl-2,4-pentanedione as the byproduct. The XRD results were observed that crystal structure of catalyst remained unchanged after the sixth run while catalytic activity slightly decreases at 97% conversion in the final run. In this reaction, the mechanistic study showed the catalytic cycle started from CuII to CuI and then oxidized to CuII by aryl iodine.[12]

The role of copper has been further emphasized in the coupling reaction of ortho-arylated phenols and dialkylformamides. It was observed that there was a single-electron oxidative addition of copperII to copperIII through a radical step, then transformed back to copperI by reductive elimination in the presence of either oxygen or peroxide. Catalyst can be reused 9 times without significant loss in catalytic activities.[26]

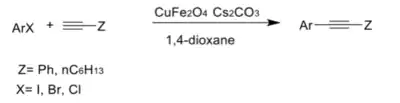

Synergistic effect of catalytic activity

Notably, synergistic effect was demonstrated for the case of CuFe2O4 in Sonogashira reaction. Both Fe and Cu center contribute to catalytic activity of the transformation between aryl halide and substituted alkynes. The product was obtained with 70% yield in the presence of Nano CuFe2O4, while only 25% yield and <1% yield observed when using CuO and Fe3O4 respectively.[27]

Mechanism of action of the catalyst

As can be noted in the examples shown above, many molecules involved in the reactions catalyzed by CuFe2O4 have a carbonyl group (C=O) or amine group (-NH2), which have electron lone pairs. These lone pairs are used to be adsorbed at the surface of the empty 3d orbital in the catalyst, and thus activate the molecules for the intended reactions. Other molecules containing functional groups with electron lone pairs such as nitro (NO2) and thiol (RS-H) also are activated by the catalyst. Species forming containing a single unpaired electron such as TEMPO or peroxymonosulphate are also adsorbed and activated to promote some organic reactions.[21]

References

- 1 2 "Cuprospinel" (PDF). Mineral Data Publishing. Retrieved 13 October 2010.

- 1 2 "Cuprospinel: Mineral information, data and localities". Mindat.org.

- ↑ "Cuprospinel Mineral Data". www.webmineral.com.

- 1 2 Ohnishi, Haruyuki; Teranishi, Teruo (1961). "Crystal Distortion in Copper Ferrite-Chromite Series". Journal of the Physical Society of Japan. 16 (1): 35–43. Bibcode:1961JPSJ...16...35O. doi:10.1143/JPSJ.16.35.

- ↑ Tranquada, J. M.; Heald, S. M.; Moodenbaugh, A. R. (1987). "X-ray-absorption near-edge-structure study of La2−x(Ba, Sr)xCuO4−y superconductors". Physical Review B. 36 (10): 5263–5274. Bibcode:1987PhRvB..36.5263T. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.36.5263. PMID 9942162.

- ↑ Birch, William D. "Who's Who in Mineral Names" (PDF). RocksAndMinerals.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 13 October 2010.

- ↑ Fleischer, Michael; Mandarino, Joseph A. (1974). "New Mineral Names" (PDF). American Mineralogist. 59: 381–384. Retrieved 13 October 2010.

- ↑ Jing Zhang; Wei Zhang; Rong Xu; Xunying Wang; Xiang Yang; Yan Wu (2017). "Electrochemical properties and catalyst functions of natural CuFe oxide mineral–LZSDC composite electrolyte". International Journal of Hydrogen Energy. 42 (34): 22185–22191. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2017.01.163.

- ↑ I.V. Pekov; F.D. Sandalov; N.N. Koshlyakova; M.F. Vigasina; Y.S. Polekhovsky; S.N. Britvin; E.G. Sidorov; A.G. Turchkova (2018). "Copper in Natural Oxide Spinels: The New Mineral Thermaerogenite CuAl2O4, Cuprospinel and Cu-Enriched Varieties of Other Spinel-Group Members from Fumaroles of the Tolbachik Volcano, Kamchatka, Russia". Minerals. 8 (11): 498. Bibcode:2018Mine....8..498P. doi:10.3390/min8110498.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 Krishnan, Venkata; Selvan, Ramakrishnan Kalai; Augustin, Chanassary Ouso; Gedanken, Aharon; Bertagnolli, Helmut (2007). "EXAFS and XANES Investigations of CuFe2O4 Nanoparticles and CuFe2O4−MO2 (M = Sn, Ce) Nanocomposites" (PDF). The Journal of Physical Chemistry C. 111 (45): 16724–16733. doi:10.1021/jp073746t.

- 1 2 3 4 Estrella, Michael; Barrio, Laura; Zhou, Gong; Wang, Xianqin; Wang, Qi; Wen, Wen; Hanson, Jonathan C.; Frenkel, Anatoly I.; Rodriguez, José A. (2009). "In Situ Characterization of CuFe2O4 and Cu/Fe3O4 Water−Gas Shift Catalysts". The Journal of Physical Chemistry C. 113 (32): 14411–14417. doi:10.1021/jp903818q.

- 1 2 3 4 Nguyen, Anh T.; Nguyen, Lan T. M.; Nguyen, Chung K.; Truong, Thanh; Phan, Nam T. S. (2014). "Superparamagnetic Copper Ferrite Nanoparticles as an Efficient Heterogeneous Catalyst for the α-Arylation of 1,3-Diketones with C–C Cleavage". ChemCatChem. 6 (3): 815–823. doi:10.1002/cctc.201300708. S2CID 97619313.

- ↑ Anandan, S.; Selvamani, T.; Prasad, G. Guru; M. Asiri, A.; J. Wu, J. (2017). "Magnetic and catalytic properties of inverse spinel CuFe2O4 nanoparticles". Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials. 432: 437–443. Bibcode:2017JMMM..432..437A. doi:10.1016/j.jmmm.2017.02.026.

- 1 2 Zhang, Wenjuan; Xue, Yongqiang; Cui, Zixiang (2017). "Effect of Size on the Structural Transition and Magnetic Properties of Nano-CuFe2O4". Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research. 56 (46): 13760–13765. doi:10.1021/acs.iecr.7b03468.

- 1 2 3 Nguyen, Anh T.; Pham, Lam T.; Phan, Nam T. S.; Truong, Thanh (2014). "Efficient and robust superparamagnetic copper ferrite nanoparticle-catalyzed sequential methylation and C–H activation: aldehyde-free propargylamine synthesis". Catalysis Science & Technology. 4 (12): 4281–4288. doi:10.1039/C4CY00753K.

- 1 2 3 4 Dandia, Anshu; Jain, Anuj K.; Sharma, Sonam (2013). "CuFe2O4 nanoparticles as a highly efficient and magnetically recoverable catalyst for the synthesis of medicinally privileged spiropyrimidine scaffolds". RSC Advances. 3 (9): 2924. Bibcode:2013RSCAd...3.2924D. doi:10.1039/C2RA22477A.

- ↑ Phuruangrat, Anukorn; Kuntalue, Budsabong; Thongtem, Somchai; Thongtem, Titipun (2016). "Synthesis of cubic CuFe2O4 nanoparticles by microwave-hydrothermal method and their magnetic properties". Materials Letters. 167: 65–68. doi:10.1016/j.matlet.2016.01.005.

- ↑ de Souza, Alexilda Oliveira; do Carmo Rangel, Maria (2003). "Catalytic activity of aluminium and copper-doped magnetite in the high temperature shift reaction". Reaction Kinetics and Catalysis Letters. 79 (1): 175–180. doi:10.1023/A:1024132406523. S2CID 189864191.

- ↑ Quadro, Emerentino Brazil; Dias, Maria de Lourdes Ribeiro; Amorim, Adelaide Maria Mendonça; Rangel, Maria do Carmo (1999). "Chromium and Copper-Doped Magnetite Catalysts for the High Temperature Shift Reaction". Journal of the Brazilian Chemical Society. 10 (1): 51–59. doi:10.1590/S0103-50531999000100009.

- 1 2 Karimi, Babak; Mansouri, Fariborz; Mirzaei, Hamid M. (2015). "Recent Applications of Magnetically Recoverable Nanocatalysts in C–C and C–X Coupling Reactions". ChemCatChem. 7 (12): 1736–1789. doi:10.1002/cctc.201403057. S2CID 97232790.

- 1 2 Ortiz-Quiñonez, Jose Luis; Pal, Umpada; Das, Sachindranath (June 2022). "Catalytic and pseudocapacitive energy storage performance of metal (Co, Ni, Cu and Mn) ferrite nanostructures and nanocomposites". Progress in Materials Science. 130: 100995. doi:10.1016/j.pmatsci.2022.100995. S2CID 249860566.

- ↑ Kantam, M. Lakshmi; Yadav, Jagjit; Laha, Soumi; Jha, Shailendra (2009). "ChemInform Abstract: Synthesis of Propargylamines by Three-Component Coupling of Aldehydes, Amines and Alkynes Catalyzed by Magnetically Separable Copper Ferrite Nanoparticles". ChemInform. 40 (49). doi:10.1002/chin.200949091.

- ↑ Tamaddon, Fatemeh; Amirpoor, Farideh (2013). "Improved Catalyst-Free Synthesis of Pyrrole Derivatives in Aqueous Media". Synlett. 24 (14): 1791–1794. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1339294. S2CID 196756104.

- ↑ Zhang, Rongzhao; Liu, Jianming; Wang, Shoufeng; Niu, Jianzhong; Xia, Chungu; Sun, Wei (2011). "Magnetic CuFe2O4 Nanoparticles as an Efficient Catalyst for C–O Cross-Coupling of Phenols with Aryl Halides". ChemCatChem. 3 (1): 146–149. doi:10.1002/cctc.201000254. S2CID 97538800.

- 1 2 Yang, Shuliang; Xie, Wenbing; Zhou, Hua; Wu, Cunqi; Yang, Yanqin; Niu, Jiajia; Yang, Wei; Xu, Jingwei (2013). "Alkoxylation reactions of aryl halides catalyzed by magnetic copper ferrite". Tetrahedron. 69 (16): 3415–3418. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2013.02.077.

- 1 2 Nguyen, Chung K.; Nguyen, Ngon N.; Tran, Kien N.; Nguyen, Viet D.; Nguyen, Tung T.; Le, Dung T.; Phan, Nam T.S. (2017). "Copper ferrite superparamagnetic nanoparticles as a heterogeneous catalyst for directed phenol/formamide coupling". Tetrahedron Letters. 58 (34): 3370–3373. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2017.07.049.

- ↑ Panda, Niranjan; Jena, Ashis Kumar; Mohapatra, Sasmita (2011). "Ligand-free Fe–Cu Cocatalyzed Cross-coupling of Terminal Alkynes with Aryl Halides". Chemistry Letters. 40 (9): 956–958. doi:10.1246/cl.2011.956.