.jpg.webp) The city of Zagreb is the capital and financial centre of Croatia. | |

| Currency | Euro (EUR, €) |

|---|---|

| 1 January – 31 December | |

Trade organisations | EU, EEA, WTO |

Country group | |

| Statistics | |

| Population | |

| GDP | |

| GDP rank | |

GDP growth | |

GDP per capita | |

GDP per capita rank | |

GDP by sector |

|

GDP by component |

|

Population below poverty line |

|

| |

Labour force | |

Labour force by occupation |

|

| Unemployment | |

Average gross salary | €1,556 monthly (January 2023)[18] |

| €1,130 monthly (January 2023)[18] | |

Main industries | chemicals and plastics, machine tools, fabricated metal, electronics, pig iron and rolled steel products, aluminium, paper, wood products, construction materials, textiles, shipbuilding, petroleum and petroleum refining, food and beverages, tourism |

| External | |

| Exports | |

Export goods | transport equipment, machinery, textiles, chemicals, foodstuffs, fuels |

Main export partners | |

| Imports | |

Import goods | machinery, transport and electrical equipment; chemicals, fuels and lubricants; foodstuffs |

Main import partners | |

FDI stock | |

Gross external debt | |

| Public finances | |

All values, unless otherwise stated, are in US dollars. | |

The economy of Croatia is a developed social market economy.[24][25] It is the largest national economy in Southeast Europe by nominal gross domestic product (GDP).[26][27] It is an open economy with accommodative foreign policy, highly dependent on international trade in Europe. Within Croatia, economic development varies among its counties, with strongest growth in Central Croatia and its financial centre, Zagreb. It has a very high level of human development,[28] low levels of wealth inequality,[29] and a high standard of living.[30] Croatia's labor market has been perennially inefficient, with inconsistent business standards as well as ineffective corporate and income tax policy.[31][32]

Croatia's economic history is closely linked to its historic nation-building efforts. Its pre-industrial economy leveraged the country's geography and natural resources to guide agricultural growth. The 1800s saw to a ship-building boom, railroading, and industrial production. During the 1900s, Croatia entered into a planned economy (with socialism) in 1941 and a command economy (with communism) during World War II. It experienced rapid urbanization in the 1950s and decentralized in 1965, diversifying its economy before the collapse of Yugoslavia during the 1990s. The Croatian War of Independence (1991-95) curbed 21–25% of wartime GDP, leaving behind a developing transition economy. As an independent state Croatia has since turned to social capitalism, aided by ongoing European integration and globalization.[33]

The modern Croatian economy is considered high-income and dominated by its tertiary service sector, which accounts for 70% of GDP. The high levels of tourism in Croatia contributes to nearly 20% of GDP, with a total of 11.2 million tourists visiting in 2021.[34][35] Croatia is an emerging energy power in the region, with strategic investments in liquefied natural gas (LNG), geothermal power, and electric automobiles.[36][37] It supports regional economic activity via transportation networks across the Adriatic Sea and throughout Pan-European corridors. As a member of the European Union, Eurozone, and Schengen Area, it uses the euro (€) as official currency.[38][39] Croatia has free-trade agreements with many world nations and is apart of the World Trade Organization (2000) and the EEA (2024).

History

Pre-20th century

When Croatia was still part of the Dual Monarchy, its economy was largely agricultural. However, modern industrial companies were also located in the vicinity of the larger cities. The Kingdom of Croatia had a high ratio of population working in agriculture. Many industrial branches developed in that time, like forestry and wood industry (stave fabrication, the production of potash, lumber mills, shipbuilding). The most profitable one was stave fabrication, the boom of which started in the 1820s with the clearing of the oak forests around Karlovac and Sisak and again in the 1850s with the marshy oak masses along the Sava and Drava rivers. Shipbuilding in Croatia played a huge role in the 1850s Austrian Empire, especially the long-range sailing boats. Sisak and Vukovar were the centres of river-shipbuilding.[40] Slavonia was also mostly an agricultural land and it was known for its silk production. Agriculture and the breeding of cattle were the most profitable occupations of the inhabitants. It produced corn of all kinds, hemp, flax, tobacco, and great quantities of liquorice.[41][42]

The first steps towards industrialization began in the 1830s and in the following decades the construction of big industrial enterprises took place.[43] During the 2nd half of the 19th and early 20th century there was an upsurge of industry in Croatia, strengthened by the construction of railways and the electric-power production. The industrial production was still lower than agricultural production.[44] Regional differences were high. Industrialization was faster in inner Croatia than in other regions, while Dalmatia remained one of the poorest provinces of Austria-Hungary.[45] The slow rate of modernization and rural overpopulation caused extensive emigration, particularly from Dalmatia. According to estimates, roughly 400,000 Croats emigrated from Austria-Hungary between 1880 and 1914. In 1910 8.5% of the population of Croatia-Slavonia lived in urban settlements.[46]

In 1918 Croatia became part of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, which was in the interwar period one of the least developed countries in Europe. Most of its industry was based in Slovenia and Croatia, but further industrial development was modest and centered on textile mills, sawmills, brick yards and food-processing plants. The economy was still traditionally based on agriculture and raising of livestock, with peasants accounting for more than half of Croatia's population.[46][47]

In 1941 the Independent State of Croatia (NDH), a World War II puppet state of Germany and Italy, was established in parts of Axis-occupied Yugoslavia. The economic system of NDH was based on the concept of "Croatian socialism".[48] The main characteristic of the new system was the concept of a planned economy with high levels of state involvement in economic life. The fulfillment of basic economic interests was primarily ensured with measures of repression.[49] All large companies were placed under state control and the property of the regime's national enemies was nationalized. Its currency was the NDH kuna. The Croatian State Bank was the central bank, responsible for issuing currency. As the war progressed the government kept printing more money and its amount in circulation was rapidly increasing, resulting in high inflation rates.[50]

After World War II, the new Communist Party of Yugoslavia converted to a command economy on the Soviet model of rapid industrial development. In accordance with the communist plan, mainly companies in the pharmaceutical industry, the food industry and the consumer goods industry were founded in Croatia. Metal and heavy industry was mainly promoted in Bosnia and Serbia. By 1948 almost all domestic and foreign-owned capital had been nationalized. The industrialization plan relied on high taxation, fixed prices, war reparations, Soviet credits, and export of food and raw materials. Forced collectivization of agriculture was initiated in 1949. At that time 94% of agricultural land was privately owned, and by 1950 96% was under the control of the social sector. A rapid improvement of food production and the standard of living was expected, but due to bad results the program was abandoned three years later.[46]

Throughout the 1950s Croatia experienced rapid urbanization. Decentralization came in 1965 and spurred growth of several sectors including a prosperous tourist industry. SR Croatia was, after SR Slovenia, the second most developed republic in Yugoslavia with a ~55% higher GDP per capita than the Yugoslav average, generating 31.5% of Yugoslav GDP or $30.1Bn in 1990.[51] Croatia and Slovenia accounted for nearly half of the total Yugoslav GDP, and this was reflected in the overall standard of living. In the mid-1960s, Yugoslavia lifted emigration restrictions and the number of emigrants increased rapidly. In 1971 224,722 workers from Croatia were employed abroad, mostly in West Germany.[52][53] Foreign remittances contributed $2 billion annually to the economy by 1990.[54] Profits gained through Croatia's industry were used to develop poor regions in other parts of former Yugoslavia, leading to Croatia contributing much more to the federal Yugoslav economy than it gained in return. This, coupled with austerity programs and hyperinflation in the 1980s, led to discontent in both Croatia and Slovenia which eventually fuelled political movements calling for independence.[55]

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, with the collapse of socialism and the beginning of economic transition, Croatia faced considerable economic problems stemming from:[56]

- the legacy of longtime communist mismanagement of the economy;

- damage during the internecine fighting to bridges, factories, power lines, buildings, and houses;

- the large refugee and displaced population, both Croatian and Bosnian;

- the disruption of economic ties; and

- inefficient privatization

At the time Croatia gained independence, its economy (and the whole Yugoslavian economy) was in the middle of recession. Privatization under the new government had barely begun when war broke out in 1991. As a result of the Croatian War of Independence, infrastructure sustained massive damage in the period 1991–92, especially the revenue-rich tourism industry. The privatization of sovereign assets and transformation from a planned economy to a market economy was thus slow and unsteady, largely as a result of public mistrust when many state-owned companies were sold to politically well-connected at below-market prices. With the end of the war, Croatia's economy recovered moderately, but corruption, cronyism, and a general lack of transparency stymied economic reforms and foreign investment.[55][57] The privatization of large government-owned companies was practically halted during the war and in the years immediately following the conclusion of peace. In 2000, roughly 70% of Croatia's major companies were still state-owned, including water, electricity, oil, transportation, telecommunications, and tourism.[58]

The early 1990s experienced high inflation. In 1991 the Croatian dinar was introduced as a transitional currency, but inflation continued to accelerate. The anti-inflationary stabilization steps in 1993 decreased retail price inflation from a monthly rate of 38.7% to 1.4%, and by the end of the year, Croatia experienced deflation. In 1994 Croatia introduced the kuna as its currency.[57] As a result of the macro-stabilization programs, the negative growth of GDP during the early 1990s stopped and reversed into a positive trend. Post-war reconstruction activity provided another impetus to growth. Consumer spending and private sector investments, both of which were postponed during the war, contributed to the growth in 1995–1997.[57] Croatia began its independence with a relatively low external debt because the debt of Yugoslavia was not shared among its former republics at the beginning. In March 1995 Croatia agreed with the Paris Club of creditor governments and took 28.5% of Yugoslavia's previously non-allocated debt over 14 years. In July 1996 an agreement was reached with the London Club of commercial creditors, when Croatia took 29.5% of Yugoslavia's debt to commercial banks. In 1997 around 60 percent of Croatia's external debt was inherited from former Yugoslavia.[59]

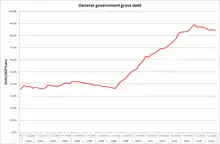

At the beginning of 1998 value-added tax was introduced. The central government budget was in surplus in that year, most of which was used to repay foreign debt.[60] Government debt to GDP had fallen from 27.30% to 26.20% at the end of 1998. However, the consumer boom was disrupted in mid 1998, as a result of the bank crisis when 14 banks went bankrupt.[57] Unemployment increased and GDP growth slowed down to 1.9%. The recession that began at the end of 1998 continued through most of 1999, and after a period of expansion GDP in 1999 had a negative growth of −0.9%.[61] In 1999 the government tightened its fiscal policy and revised the budget with a 7% cut in spending.[62]

In 1999 the private sector share in GDP reached 60%, which was significantly lower than in other former socialist countries. After several years of successful macroeconomic stabilization policies, low inflation and a stable currency, economists warned that the lack of fiscal changes and the expanding role of the state in the economy caused the decline in the late 1990s and were preventing sustainable economic growth.[59][62]

| Year | GDP growth | Deficit/surplus* | Debt to GDP | Privatization revenues* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | 5.9% | 1.8% | 22.2% | |

| 1995 | 6.8% | −0.7% | 19.3% | 0.9% |

| 1996 | 5.9% | −0.4% | 28.5% | 1.4% |

| 1997 | 6.6% | −1.2% | 27.3% | 2.0% |

| 1998 | 1.9% | 0.5% | 26.2% | 3.6% |

| 1999 | −0.9% | −2.2% | 28.5% | 8.2% |

| 2000 | 3.8% | −5.0% | 34.3% | 10.2% |

| 2001 | 3.4% | −3.2% | 35.2% | 13.5% |

| 2002 | 5.2% | −2.6% | 34.8% | 15.8% |

| *Including capital revenues *cumulative, in % of GDP | ||||

21st century

The new government led by the president of SDP, Ivica Račan, carried out a number of structural reforms after it won the parliamentary elections on 3 January 2000. The country emerged from the recession in the 4th quarter of 1999 and growth picked up in 2000.[63] Due to overall increase in stability, the economic rating of the country improved and interest rates dropped. Economic growth in the 2000s was stimulated by a credit boom led by newly privatized banks, capital investment, especially in road construction, a rebound in tourism and credit-driven consumer spending. Inflation remained tame and the currency, the kuna, stable.[55][64] In 2000 Croatia generated 5,899 billion kunas in total income from the shipbuilding sector, which employed 13,592 people. Total exports in 2001 amounted to $4,659,286,000, of which 54.7% went to the countries of the EU. Croatia's total imports were $9,043,699,000, 56% of which originated from the EU.[65]

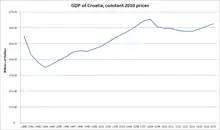

Unemployment reached its peak in late 2002, but has since been steadily declining. In 2003, the nation's economy would officially recover to the amount of GDP it had in 1990.[66] In late 2003 the new government led by HDZ took over the office. Unemployment continued falling, powered by growing industrial production and rising GDP, rather than only seasonal changes from tourism. Unemployment reached an all-time low in 2008 when the annual average rate was 8.6%,[67] GDP per capita peaked at $16,158,[61] while public debt as percentage of GDP decreased to 29%. Most economic indicators remained positive in this period except for the external debt as Croatian firms focused more on empowering the economy by taking loans from foreign resources.[66] Between 2003 and 2007, Croatia's private-sector share of GDP increased from 60% to 70%.[68] The Croatian National Bank took steps to curb further growth of indebtedness of local banks with foreign banks. The dollar debt figure is adversely affected by the EUR-USD ratio—over a third of the increase in debt since 2002 is due to currency value changes.

Economic growth has been hurt by the global financial crisis.[69] Immediately after the crisis it seemed that Croatia did not suffer serious consequences like some other countries. However, in 2009, the crisis gained momentum and the decline in GDP growth, at a slower pace, continued during 2010. In 2011 the GDP stagnated as the growth rate was zero.[70] Since the global crisis hit the country, the unemployment rate has been steadily increasing, resulting in the loss of more than 100,000 jobs.[71] While unemployment was 9.6% in late 2007,[72] in January 2014 it peaked at 22.4%.[73] In 2010 Gini coefficient was 0,32.[74] In September 2012, Fitch ratings agency unexpectedly improved Croatia's economic outlook from negative to stable, reaffirming Croatia's current BBB rating.[75] The slow pace of privatization of state-owned businesses and an over-reliance on tourism have also been a drag on the economy.[69]

Croatia joined the European Union on 1 July 2013 as the 28th member state. The Croatian economy is heavily interdependent on other principal economies of Europe, and any negative trends in these larger EU economies also have a negative impact on Croatia. Italy, Germany and Slovenia are Croatia's most important trade partners.[70] In spite of the rather slow post-recession recovery, in terms of income per capita it is still ahead of some European Union member states such as Bulgaria, and Romania.[76] In terms of average monthly wage, Croatia is ahead of 9 EU members (Czech Republic, Estonia, Slovakia, Latvia, Poland, Hungary, Lithuania, Romania, and Bulgaria).[77]

The annual average unemployment rate in 2014 was 17.3% and Croatia has the third-highest unemployment rate in the European Union, after Greece (26.5%), and Spain (24.%).[67] Of particular concern is the heavily backlogged judiciary system, combined with inefficient public administration, especially regarding the issues of land ownership and corruption in the public sector. Unemployment is regionally uneven: it is very high in eastern and southern parts of the country, nearing 20% in some areas, while relatively low in the north-west and in larger cities, where it is between 3 and 7%. In 2015 external debt rose by €2.7 billion since the end of 2014 and is now around €49.3 billion.

2016–2019

During 2015 the Croatian economy started with slow but upward economic growth, which continued during 2016 and conclusive at the end of the year seasonally adjusted was recorded at 3.5%.[78] The better than expected figures during 2016 enabled the Croatian Government and with more tax receipts enabled the repayment of debt as well as narrow the current account deficit during Q3 and Q4 of 2016[79][80] This growth in economic output, coupled with the reduction of government debt has made a positive impact on the financial markets with many ratings agencies revising their outlook from negative to stable, which was the first upgrade of Croatia's credit rating since 2007.[81] Due to consecutive months of economic growth and the demand for labour, plus the outflows of residents to other European countries, Croatia had recorded the biggest fall in the number of unemployed during the month of November 2016 from 16.1% to 12.7%.

2020

COVID-19 Pandemic has caused more than 400,000 workers to file for economic aid of 4000.00 HRK./month. In the first quarter of 2020, Croatian GDP rose by 0.2% but then in Q2 Government of Croatia announced the biggest quarterly GDP plunge of -15.1% since GDP has been measured. Economic activity also plunged in Q3 2020 when GDP slid by an additional -10.0%.

In autumn 2020 European Commission estimated total GDP loss in 2020 to be -9.6%. Growth was set to pick up in the last month of Q1 2021 and the second quarter of 2021 respectively +1.4% and +3.0%, meaning that Croatia was set to reach 2019 levels by 2022.[82]

2021

In July 2021 projection was improved to 5.4% due to the strong outturn in the first quarter and the positive high-frequency indicators concerning consumption, construction, industry and tourism prospects.[83] In November 2021 Croatia outperformed these projections and the real GDP growth was calculated to be 8.1% for the year 2021, improving its projection of 5.4% GDP growth made in July.[84] The recovery was supported by strong private consumption, the better-than-expected performance of tourism and the ongoing resilience of the export sector. Preliminary data point to tourism-related expenditure already exceeding 2019 levels, which has been supportive of both employment and consumption. Exports of goods have also continued to perform strongly (up 43%yoy in 2Q21) pointing to resilient competitiveness.[85] Croatian merchandise exports in the first nine months of 2021 amounted to €13.3 billion, an annual increase of 24.6%. At the same time, imports rose 20.3% to €20.4 billion. The coverage of imports by exports for the first nine months is 65.4%.[86] This made 2021 Croatian export's record year as the trade off-set from 2019 was exceeded by €2 billion.[87]

Exports recovered in all major markets, more precisely with all EU countries and CEFTA countries. Specifically, on the EU market, only a lower export result is recorded in relations with Sweden, Belgium and Luxembourg. Italy is again the main market for Croatian products, followed by Germany and Slovenia. Apart from the high contribution of crude oil that Ina sends to Hungary to the Mol refinery for processing, the export of artificial fertilizers from Petrokemija also has a significant contribution to growth.

For 2022, the Commission revised downwards its projection for Croatia's economic growth to 5.6% from 5.9% previously predicted in July 2021. Commission again confirmed that the volume of Croatia's GDP should reach its 2019 level during 2022, while in 2023 the GDP will grow by 3.4%. The Commission warned that the key downside risks stem from Croatia's relatively low vaccination rates, which could lead to stricter containment measures, and continued delays of the earthquake-related reconstruction. Croatia's entry into the Schengen area and euro adoption towards the end of the forecast period could benefit investment and trade.

On Friday, 12 November 2021 Fitch raised Croatia's credit rating by one level, from ‘BBB−‘ to ‘BBB’, Croatia's highest credit rating in history,[88] with a positive outlook, noting progress in preparations for Eurozone membership and a strong recovery of the Croatian economy from the pandemic crisis.[89] This is also secured by the failure of the eurosceptic party Hrvatski Suverenisti in a bid on the referendum to block Euro adoption in Croatia.[90] In December 2021 Croatia's industrial production increased for the thirteenth consecutive month,[91] observing the growth of production increasing in all of the five aggregates.[92] meaning that industrial production in 2021 increased by 6.7 percent.[93]

In 2021 Croatia joined the list of countries with its own automobile industry,[94] with Rimac Automobili's Nevera started being produced. The company also took over Bugatti Automobiles in November same year and started building its new HQ in Zagreb, titled as the "Rimac Campus", that will serve as the company’s international research and development (R&D) and production base for all future Rimac products, as well as home of R&D for future Bugatti models. The company also plans to build battery systems for different manufacturers from the automotive industry[95][96] This campus will also become the home of R&D for future Bugatti models due to the new joint venture, though these vehicles will be built at Bugatti’s Molsheim plant in France.

2022

In late March 2022 Croatian Bureau of Statistics announced that Croatia's industrial output rose by 4% in February, thus growing for 15 months in a row.[97][98] Croatia continued to have strong growth during 2022 fuelled by tourism revenue[99] and increased exports.[100][101] According to a preliminary estimate, Croatia's GDP in Q2 grew by 7.7% from the same period of 2021.[102] The International Monetary Fund (IMF) projected in early September 2022 that Croatia's economy will expand by 5.9% in 2022, whilst EBRD expects Croatian GDP growth to reach 6.5% by the end of 2022.[103] Pfizer announced launching a new production plant in Savski Marof[104] whilst Croatian IT industry grew 3.3%[105][106] confirming the trend that started with Coronavirus pandemic where the Croatia's digital economy increased by 16 percent on average annually from 2019 to 2021. It is estimated that by 2030 its value could reach 15 percent of GDP, with the ICT sector being the main driver of that growth.[107]

In 2022, Croatian economy is expected to grow between 5.9 and 7.8% in real terms and it is expected to reach between $72 and $73.6 billion according to preliminary estimates by Croatian Government surpassing early estimates of 491 billion kuna or $68.5 billion. Croatian Purchasing Power Parity in 2022 for the first time should exceed $40 000, however considering Croatian economy experienced 6 years of deep recession, catching up will take several more years of high growth. Economic outlook for 2023 for Croatian economy are mixed, depends largely on how the big Eurozone economies perform, Croatia's largest trading partners; Italy, Germany, Austria, Slovenia and France are expected to slow down, but avoid recession according to latest economic projections and estimates, so Croatian economy as a result could see better than expected results in 2023, early projections of between 1 and 2.6% economic growth in 2023 with inflation at 7% is a significant slow down for the country, however country is experiencing major internal and inward investment cycle unparalleled in recent history. EU recovery funds [108] in tune of €8.7 billion coupled with large EU investments in recently earthquake affected areas of Croatia, as well as major investments by local business in to renewable energy sector, also EU supported and funded, as well as major investments in transport infrastructure and rapidly expanding Croatia's ICT sector, Croatian economy could see continuation of rapid growth in 2023.

On 12 July 2022, the Eurogroup approved Croatia becoming the 20th member of the Eurozone, with the formal introduction of the Euro currency to take place on 1 January 2023.[109][110] Croatia joined the Schengen Area in 2023.[39] By 2023, the minimum wage is ostensibly expected to rise to NET 700 EUR,[111][112][113] increasing consumer spending.[38]

Sectors

In 2022, the sector with the highest number of companies registered in Croatia is Services with 110,085 companies followed by Retail Trade and Construction with 22,906 and 22,121 companies respectively.[114]

Industry

Tourism

Cruise ship in Dubrovnik.

Cruise ship in Dubrovnik. Kopački Rit Nature Reserve.

Kopački Rit Nature Reserve..jpg.webp) St. Mark's Church in Zagreb.

St. Mark's Church in Zagreb. Varaždin Old Town.

Varaždin Old Town. Zlatni Rat beach on the Brač island.

Zlatni Rat beach on the Brač island.

Tourism is a notable source of income during the summer and a major industry in Croatia. It dominates the Croatian service sector and accounts for up to 20% of Croatian GDP. Annual tourist industry income for 2011 was estimated at €6.61 billion. Its positive effects are felt throughout the economy of Croatia in terms of increased business volume observed in retail business, processing industry orders and summer seasonal employment. The industry is considered an export business, because it significantly reduces the country's external trade imbalance.[115] Since the conclusion of the Croatian War of Independence, the tourist industry has grown rapidly, recording a fourfold rise in tourist numbers, with more than 10 million tourists each year. The most numerous are tourists from Germany, Slovenia, Austria and the Czech Republic as well as Croatia itself. Length of a tourist stay in Croatia averages 4.9 days.[116]

The bulk of the tourist industry is concentrated along the Adriatic Sea coast. Opatija was the first holiday resort since the middle of the 19th century. By the 1890s, it became one of the most significant European health resorts.[117] Later a large number of resorts sprang up along the coast and numerous islands, offering services ranging from mass tourism to catering and various niche markets, the most significant being nautical tourism, as there are numerous marinas with more than 16 thousand berths, cultural tourism relying on appeal of medieval coastal cities and numerous cultural events taking place during the summer. Inland areas offer mountain resorts, agrotourism and spas. Zagreb is also a significant tourist destination, rivalling major coastal cities and resorts.[118]

Croatia has unpolluted marine areas reflected through numerous nature reserves and 99 Blue Flag beaches and 28 Blue Flag marinas.[119] Croatia is ranked as the 18th most popular tourist destination in the world.[120] About 15% of these visitors (over one million per year) are involved with naturism, an industry for which Croatia is world-famous. It was also the first European country to develop commercial naturist resorts.[121]

Agriculture

Croatian agricultural sector subsists from exports of blue water fish, which in recent years experienced a tremendous surge in demand, mainly from Japan and South Korea. Croatia is a notable producer of organic foods and much of it is exported to the European Union. Croatian wines, olive oil and lavender are particularly sought after. Value of Croatia's agriculture sector is around 3.1 billion according to preliminary data released by the national statistics office.[122]

Croatia has around 1.72 million hectares of agricultural land, however totally utilized land for agricultural in 2020 was around 1.506 million hectares, of these permanent pasture land constituted 536 000 hectares or some 35.5% of total land available to agriculture. Croatia imports significant quantity of fruits and olive oil, despite having large domestic production of the same. In terms of livestock Croatian agriculture had some 15.2 million poultry, 453 000 Cattle, 802 000 Sheep, 1.157 000 Pork/Pigs,88 000 Goats. Croatia also produced 67 000 tons of blue fish, some 9000 of these are Tuna fish, which are farmed and exported to Japan, South Korea and United States.[123]

Croatia produced in 2022:[124]

- 1.66 million tons of maize;

- 970 thousand tons of wheat;

- 524 thousand tons of sugar beet (the beet is used to manufacture sugar and ethanol);

- 319 thousand tons of barley;

- 196 thousand tons of soybean;

- 107 thousand tons of potato;

- 59 thousand tons of rapeseed;

- 146 thousand tons of grape;

- 154 thousand tons of sunflower seed;

In addition to smaller productions of other agricultural products, like apple (93 thousand tons), triticale (62 thousand tons) and olive (34 thousand tons).[125]

Transport

.JPG.webp)

The highlight of Croatia's recent infrastructure developments is its rapidly developed motorway network, largely built in the late 1990s and especially in the 2000s. By January 2022, Croatia had completed more than 1,300 kilometres (810 miles) of motorways, connecting Zagreb to most other regions and following various European routes and four Pan-European corridors.[126][127] The busiest motorways are the A1, connecting Zagreb to Split and the A3, passing east–west through northwest Croatia and Slavonia.[128] A widespread network of state roads in Croatia acts as motorway feeder roads while connecting all major settlements in the country. The high quality and safety levels of the Croatian motorway network were tested and confirmed by several EuroTAP and EuroTest programs.[129][130]

Croatia has an extensive rail network spanning 2,722 kilometres (1,691 miles), including 985 kilometres (612 miles) of electrified railways and 254 kilometres (158 miles) of double track railways. The most significant railways in Croatia are found within the Pan-European transport corridors Vb and X connecting Rijeka to Budapest and Ljubljana to Belgrade, both via Zagreb.[126] All rail services are operated by Croatian Railways.[131]

There are international airports in Zagreb, Zadar, Split, Dubrovnik, Rijeka, Osijek and Pula.[132] As of January 2011, Croatia complies with International Civil Aviation Organization aviation safety standards and the Federal Aviation Administration upgraded it to Category 1 rating.[133]

The busiest cargo seaport in Croatia is the Port of Rijeka and the busiest passenger ports are Split and Zadar.[134][135] In addition to those, a large number of minor ports serve an extensive system of ferries connecting numerous islands and coastal cities in addition to ferry lines to several cities in Italy.[136] The largest river port is Vukovar, located on the Danube, representing the nation's outlet to the Pan-European transport corridor VII.[126][137]

Energy

There are 631 kilometres (392 miles) of crude oil pipelines in Croatia, connecting the JANAF oil terminal with refineries in Rijeka and Sisak, as well as several transhipment terminals. The system has a capacity of 20 million tonnes per year.[138] The natural gas transportation system comprises 2,544 kilometres (1,581 miles) of trunk and regional natural gas pipelines, and more than 300 associated structures, connecting production rigs, the Okoli natural gas storage facility, 27 end-users and 37 distribution systems.[139]

Croatian production of energy sources covers 29% of nationwide natural gas demand and 26% of oil demand. In 2022, net total electrical power production in Croatia reached 13,696 GWh and Croatia imported 28% of its electric power energy needs. The bulk of Croatian imports are supplied by the Krško Nuclear Power Plant in Slovenia, 50% owned by Hrvatska elektroprivreda, providing 14% of Croatia's electricity.[140]

Electricity:[141]

- production: 13,696 GWh (2022)

- consumption: 18,391 GWh (2022)

- exports: 7,225 GWh (2022)

- imports: 11,920 GWh (2022)

Electricity – production by source:[140]

- hydro: 26% (2022)

- thermal: 24% (2022)

- nuclear: 14% (2022)

- renewable: 8% (2022)

- import: 28% (2022)

Crude oil:[142]

- production: 594 thousand tons (2022)

- consumption: 2.306 million tons (2022)

- exports: 202 thousand tons (2022)

- imports: 1,979 million tons (2022)

- proved reserves: 3,568,700 cubic metres (22,446,000 bbl) (2021)[143]

Natural gas:[141]

- production: 745 million m³ (2022)

- consumption: 2,529 billion m³ (2022)

- exports: 1,063 million m³ (2022)

- imports: 3,022 billion m³ (2022)

- proved reserves: 16,717.5 million m³ (2021)[143]

Banking

Central bank

The country's monetary policy is formulated and implemented by its national bank.

Retail banks

- Zagrebačka banka (owned by UniCredit from Italy)

- Privredna banka Zagreb (owned by Intesa Sanpaolo from Italy)

- Hrvatska poštanska banka

- OTP Banka (owned by OTP Bank from Hungary)

- Raiffeisen Bank Austria (owned by Raiffeisen from Austria)

- Erste & Steiermärkische Bank (former Riječka banka, owned by Erste Bank from Austria)

Central budget

The central budget is set by the Government of Croatia to cover their upcoming fiscal year, which runs from 1 January to 31st December. For 2024, they reported €28.52 billion in revenue with €32.61 billion in expenditure, running a €4.09 billion budget deficit.[144]

The breakdown of Croatia's budget for 2023, by ministry (department), is shown below.[144]

- Labor and Pension System, Family and Social Policy – €10.59 billion

- Finance – €7.15 billion

- Health – €4.29 billion

- Science and Education – €3.84 billion

- Economy and Sustainable Development – €2.19 billion

- Maritime Affairs, Transport and Infrastructure – €1.56 billion

- Agriculture – €1.22 billion

- Interior – €1.18 billion

- Defence – €1.17 billion

- Physical Planning, Construction and State Property – €0.74 billion

- Justice and Public Administration – €0.68 billion

- Culture and Media – €0.54 billion

- Regional Development and EU funds – €0.42 billion

- Tourism and Sport – €0.28 billion

- Veterans' Affairs – €0.17 billion

- Foreign and European Affairs – €0.15 billion

Stock exchanges

Economic indicators

The following table shows the main economic indicators for the period 2000–2022 according to the Croatian Bureau of Statistics.[21][145]

| Year | Population (in million) | GDP (in Bil. US$ PPP) | GDP

(in Bil. EUR nominal) |

GDP

(in Bil. US$ nominal) |

GDP per capita (EUR nominal) | GDP per capita (US$ nominal) | GDP per capita (PPP in USD) | Exchange rate (1 USD to 1 EUR) | Inflation (in %) | GDP growth (real in %) | Government debt (% GDP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 4.426 | 47.7 | 24.0 | 21.8 | 5,351 | 4,929 | 10,786 | 0.9236 | 4.6 | 2.9 | 35.4 |

| 2001 | 4.300 | 50.1 | 25.8 | 23.3 | 6,044 | 5,414 | 11,655 | 0.8956 | 3.8 | 3.0 | 36.6 |

| 2002 | 4.302 | 55.0 | 28.3 | 27.1 | 6,688 | 6,293 | 12,771 | 0.9456 | 1.7 | 5.7 | 36.5 |

| 2003 | 4.303 | 58.9 | 31.2 | 35.0 | 7,206 | 8,130 | 13,682 | 1.1312 | 1.8 | 5.5 | 37.9 |

| 2004 | 4.305 | 63.3 | 33.6 | 42.0 | 7,847 | 9,752 | 14,675 | 1.2439 | 2.1 | 4.1 | 40.0 |

| 2005 | 4.310 | 66.6 | 36.2 | 45.8 | 8,539 | 10,620 | 15,439 | 1.2441 | 3.3 | 4.3 | 40.9 |

| 2006 | 4.311 | 75.9 | 39.4 | 50.9 | 9,405 | 11,795 | 17,596 | 1.2556 | 3.2 | 4.9 | 38.5 |

| 2007 | 4.310 | 84.1 | 43.2 | 60.6 | 10,272 | 14,043 | 19,491 | 1.3705 | 2.9 | 4.9 | 37.2 |

| 2008 | 4.310 | 90.4 | 46.5 | 71.0 | 11,216 | 16,419 | 20,924 | 1.4708 | 6.1 | 1.9 | 39.1 |

| 2009 | 4.305 | 87.1 | 44.4 | 63.4 | 10,549 | 14,663 | 20,147 | 1.3948 | 2.4 | -7.3 | 48.4 |

| 2010 | 4.295 | 86.1 | 44.3 | 60.7 | 10,615 | 14,062 | 19,965 | 1.3257 | 1.1 | -1.3 | 57.3 |

| 2011 | 4.281 | 90.3 | 45.0 | 63.4 | 10,608 | 14,758 | 21,013 | 1.3920 | 2.3 | -0.1 | 63.7 |

| 2012 | 4.268 | 91.6 | 44.5 | 57.4 | 10,430 | 13,400 | 21,398 | 1.2848 | 3.4 | -2.3 | 69.4 |

| 2013 | 4.256 | 94.2 | 44.7 | 59.0 | 10,423 | 13,869 | 22,135 | 1.3281 | 2.2 | -0.4 | 80.3 |

| 2014 | 4.238 | 94.8 | 44.6 | 58.4 | 10,386 | 13,783 | 22,366 | 1.3285 | -0.2 | -0.4 | 83.9 |

| 2015 | 4.204 | 98.1 | 45.7 | 50.7 | 10,755 | 11,944 | 23,339 | 1.1095 | -0.5 | 2.5 | 83.3 |

| 2016 | 4.174 | 105.4 | 47.3 | 52.4 | 11,324 | 12,557 | 25,262 | 1.1069 | -1.1 | 3.6 | 79.8 |

| 2017 | 4.125 | 112.2 | 49.5 | 55.9 | 12,101 | 13,657 | 27,201 | 1.1297 | 1.1 | 3.4 | 76.7 |

| 2018 | 4.088 | 118.2 | 51.9 | 61.3 | 12,896 | 15,245 | 28,909 | 1.1810 | 1.5 | 2.8 | 73.3 |

| 2019 | 4.065 | 124.3 | 54.8 | 61.3 | 13,678 | 15,333 | 30,585 | 1.1195 | 0.8 | 3.4 | 71.1 |

| 2020 | 4.048 | 117.0 | 50.5 | 57.6 | 12,408 | 14,205 | 28,911 | 1.1422 | 0.1 | -8.6 | 87.3 |

| 2021 | 3.879 | 134.0 | 58.2 | 68.8 | 15,006 | 17,747 | 34,533 | 1.1827 | 2.6 | 13.1 | 78.3 |

| 2022 | 3.854 | 155.1 | 67.4 | 71.0 | 17,486 | 18,412 | 40,240 | 1.0530 | 10.8 | 6.3 | 70.4 |

Economic output

| Counties of Croatia by GDP, in million Euro | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| County | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

| 520 | 569 | 639 | 645 | 688 | 698 | 800 | 804 | 953 | 917 | 834 | 823 | 786 | 790 | 789 | 809 | 855 | 874 | 925 | |

| 564 | 628 | 687 | 713 | 779 | 771 | 849 | 918 | 1,032 | 952 | 914 | 917 | 895 | 888 | 853 | 879 | 917 | 969 | 1,016 | |

| 573 | 630 | 676 | 754 | 883 | 977 | 1,083 | 1,292 | 1,340 | 1,267 | 1,248 | 1,208 | 1,202 | 1,234 | 1,260 | 1,313 | 1,403 | 1,532 | 1,587 | |

| 1,420 | 1,614 | 1,814 | 1,980 | 2,182 | 2,291 | 2,482 | 2,729 | 2,842 | 2,768 | 2,773 | 2,762 | 2,635 | 2,631 | 2,666 | 2,747 | 2,947 | 3,106 | 3,162 | |

| 586 | 713 | 785 | 758 | 777 | 835 | 943 | 1,048 | 1,107 | 998 | 969 | 978 | 948 | 961 | 934 | 961 | 1,008 | 1,031 | 1,035 | |

| 723 | 762 | 830 | 845 | 853 | 855 | 988 | 1,046 | 1,069 | 998 | 935 | 926 | 906 | 919 | 905 | 916 | 961 | 991 | 979 | |

| 569 | 655 | 681 | 706 | 729 | 815 | 858 | 947 | 974 | 868 | 807 | 815 | 803 | 823 | 837 | 867 | 928 | 990 | 1,021 | |

| 235 | 250 | 309 | 384 | 522 | 407 | 429 | 417 | 491 | 445 | 416 | 405 | 382 | 388 | 379 | 388 | 402 | 427 | 436 | |

| 510 | 562 | 644 | 654 | 691 | 737 | 841 | 892 | 1,034 | 977 | 933 | 941 | 929 | 1,088 | 959 | 986 | 1,045 | 1,109 | 1,142 | |

| 1,352 | 1,459 | 1,668 | 1,700 | 1,872 | 2,043 | 2,249 | 2,600 | 2,834 | 2,642 | 2,507 | 2,514 | 2,421 | 2,438 | 2,375 | 2,436 | 2,544 | 2,581 | 2,572 | |

| 325 | 355 | 380 | 420 | 451 | 464 | 478 | 508 | 554 | 504 | 497 | 482 | 458 | 461 | 433 | 440 | 453 | 466 | 499 | |

| 2,111 | 2,138 | 2,261 | 2,543 | 2,685 | 3,066 | 3,371 | 3,560 | 4,060 | 3,820 | 3,822 | 3,905 | 3,981 | 3,849 | 3,849 | 3,854 | 3,961 | 4,177 | 4,270 | |

| 925 | 938 | 972 | 989 | 1,033 | 1,137 | 1,335 | 1,262 | 1,435 | 1,447 | 1,451 | 1,439 | 1,434 | 1,306 | 1,221 | 1,268 | 1,247 | 1,266 | 1,309 | |

| 1,924 | 2,118 | 2,318 | 2,529 | 2,898 | 3,061 | 3,427 | 3,934 | 4,115 | 3,804 | 3,788 | 3,695 | 3,578 | 3,583 | 3,581 | 3,712 | 3,913 | 4,133 | 4,278 | |

| 423 | 450 | 511 | 581 | 659 | 748 | 765 | 902 | 923 | 802 | 859 | 856 | 835 | 851 | 852 | 862 | 903 | 988 | 1,027 | |

| 894 | 996 | 1,139 | 1,175 | 1,166 | 1,229 | 1,347 | 1,451 | 1,637 | 1,549 | 1,463 | 1,456 | 1,436 | 1,467 | 1,462 | 1,506 | 1,601 | 1,718 | 1,865 | |

| 357 | 406 | 438 | 458 | 471 | 476 | 555 | 590 | 615 | 546 | 516 | 526 | 504 | 496 | 455 | 460 | 485 | 500 | 536 | |

| 624 | 686 | 762 | 816 | 864 | 928 | 1,079 | 1,109 | 1,260 | 1,171 | 1,090 | 1,092 | 1,049 | 1,048 | 999 | 1,031 | 1,076 | 1,120 | 1,171 | |

| 627 | 733 | 829 | 982 | 1,055 | 1,166 | 1,238 | 1,443 | 1,618 | 1,478 | 1,405 | 1,383 | 1,366 | 1,386 | 1,395 | 1,445 | 1,527 | 1,671 | 1,797 | |

| 1,284 | 1,272 | 1,583 | 1,653 | 1,823 | 2,059 | 2,128 | 2,419 | 2,653 | 2,555 | 2,398 | 2,449 | 2,439 | 2,450 | 2,466 | 2,549 | 2,651 | 2,832 | 3,011 | |

| 6,912 | 7,806 | 8,569 | 9,458 | 10,400 | 11,717 | 12,954 | 14,059 | 15,439 | 14,561 | 15,586 | 15,383 | 15,055 | 14,778 | 14,754 | 15,206 | 15,818 | 16,782 | 17,544 | |

| Source: Croatian Bureau of Statistics[146] | |||||||||||||||||||

| Counties of Croatia by GDP per capita, in Euro | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| County | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

| 4,007 | 4,383 | 4,951 | 5,042 | 5,417 | 5,539 | 6,395 | 6,489 | 7,756 | 7,522 | 6,907 | 6,888 | 6,657 | 6,766 | 6,829 | 7,107 | 7,647 | 7,958 | 7,986 | |

| 3,425 | 3,812 | 4,171 | 4,345 | 4,766 | 4,731 | 5,223 | 5,660 | 6,384 | 5,921 | 5,731 | 5,789 | 5,691 | 5,700 | 5,539 | 5,810 | 6,195 | 6,726 | 6,607 | |

| 4,886 | 5,373 | 5,738 | 6,378 | 7,442 | 8,197 | 9,025 | 10,698 | 11,024 | 10,351 | 10,174 | 9,855 | 9,812 | 10,083 | 10,297 | 10,737 | 11,500 | 12,608 | 13,277 | |

| 7,184 | 8,160 | 9,117 | 9,880 | 10,813 | 11,267 | 12,116 | 13,221 | 13,691 | 13,285 | 13,297 | 13,270 | 12,684 | 12,665 | 12,811 | 13,199 | 14,165 | 14,915 | 15,570 | |

| 4,181 | 5,082 | 5,635 | 5,491 | 5,666 | 6,139 | 6,989 | 7,830 | 8,341 | 7,598 | 7,458 | 7,615 | 7,461 | 7,651 | 7,541 | 7,868 | 8,373 | 8,701 | 8,301 | |

| 5,955 | 6,269 | 6,858 | 7,025 | 7,134 | 7,181 | 8,335 | 8,878 | 9,108 | 8,545 | 8,052 | 8,020 | 7,890 | 8,039 | 7,969 | 8,149 | 8,660 | 9,066 | 8,711 | |

| 4,089 | 4,702 | 4,919 | 5,129 | 5,323 | 5,972 | 6,313 | 7,008 | 7,250 | 6,479 | 6,049 | 6,142 | 6,091 | 6,287 | 6,439 | 6,721 | 7,265 | 7,830 | 7,919 | |

| 4,219 | 4,493 | 5,582 | 6,965 | 9,466 | 7,446 | 7,927 | 7,783 | 9,277 | 8,515 | 8,091 | 7,984 | 7,652 | 7,874 | 7,812 | 8,134 | 8,571 | 9,297 | 8,878 | |

| 4,472 | 4,930 | 5,644 | 5,729 | 6,056 | 6,459 | 7,375 | 7,830 | 9,086 | 8,583 | 8,196 | 8,273 | 8,176 | 9,592 | 8,480 | 8,751 | 9,328 | 9,989 | 10,302 | |

| 4,247 | 4,582 | 5,239 | 5,354 | 5,914 | 6,480 | 7,174 | 8,353 | 9,162 | 8,578 | 8,183 | 8,249 | 7,990 | 8,105 | 7,965 | 8,270 | 8,779 | 9,098 | 8,684 | |

| 3,904 | 4,255 | 4,572 | 5,066 | 5,479 | 5,658 | 5,874 | 6,286 | 6,897 | 6,330 | 6,314 | 6,194 | 5,971 | 6,081 | 5,774 | 5,973 | 6,307 | 6,681 | 6,620 | |

| 7,123 | 7,210 | 7,622 | 8,575 | 9,051 | 10,326 | 11,337 | 11,959 | 13,642 | 12,847 | 12,873 | 13,185 | 13,474 | 13,061 | 13,103 | 13,204 | 13,686 | 14,559 | 14,797 | |

| 4,884 | 4,952 | 5,158 | 5,285 | 5,552 | 6,156 | 7,292 | 6,966 | 8,018 | 8,184 | 8,321 | 8,372 | 8,465 | 7,832 | 7,459 | 7,899 | 7,939 | 8,284 | 7,868 | |

| 4,422 | 4,866 | 5,278 | 5,723 | 6,508 | 6,820 | 7,593 | 8,684 | 9,059 | 8,361 | 8,323 | 8,121 | 7,866 | 7,876 | 7,876 | 8,184 | 8,655 | 9,183 | 9,636 | |

| 3,855 | 4,094 | 4,631 | 5,254 | 5,946 | 6,733 | 6,863 | 8,081 | 8,262 | 7,202 | 7,788 | 7,855 | 7,764 | 7,998 | 8,086 | 8,267 | 8,776 | 9,737 | 9,713 | |

| 4,952 | 5,516 | 6,327 | 6,550 | 6,525 | 6,890 | 7,564 | 8,165 | 9,233 | 8,758 | 8,298 | 8,281 | 8,193 | 8,412 | 8,434 | 8,752 | 9,389 | 10,176 | 10,899 | |

| 3,887 | 4,416 | 4,793 | 5,029 | 5,222 | 5,329 | 6,253 | 6,703 | 7,048 | 6,326 | 6,037 | 6,213 | 6,012 | 5,979 | 5,542 | 5,704 | 6,135 | 6,480 | 6,525 | |

| 3,277 | 3,604 | 4,018 | 4,330 | 4,617 | 4,985 | 5,825 | 6,012 | 6,853 | 6,401 | 6,016 | 6,094 | 5,856 | 5,961 | 5,772 | 6,082 | 6,498 | 6,999 | 6,730 | |

| 4,050 | 4,726 | 5,289 | 6,193 | 6,579 | 7,186 | 7,534 | 8,676 | 9,640 | 8,752 | 8,281 | 8,114 | 7,985 | 8,084 | 8,146 | 8,478 | 9,003 | 9,901 | 10,803 | |

| 4,327 | 4,283 | 5,279 | 5,459 | 5,966 | 6,686 | 6,859 | 7,745 | 8,443 | 8,089 | 7,565 | 7,703 | 7,660 | 7,687 | 7,748 | 8,050 | 8,434 | 9,083 | 9,710 | |

| 8,962 | 10,114 | 11,091 | 12,238 | 13,418 | 15,082 | 16,642 | 18,005 | 19,709 | 18,526 | 19,765 | 19,453 | 18,986 | 18,578 | 18,479 | 18,992 | 19,711 | 20,879 | 22,695 | |

| Source: Croatian Bureau of Statistics[146] | |||||||||||||||||||

See also

References

- ↑ "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2023". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- ↑ "World Bank Country and Lending Groups". datahelpdesk.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- ↑ "Census of population, households and dwellings in 2021 - Population by towns/municipalities". Croatian Bureau of Statistics. 7 October 2022. Archived from the original on 9 December 2022. Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects: April 2023". imf.org. International Monetary Fund.

- 1 2 3 "The outlook is uncertain again amid financial sector turmoil, high inflation, ongoing effects of Russia's invasion of Ukraine, and three years of COVID". International Monetary Fund. 11 April 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 "Croatia". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 4 February 2019. (Archived 2019 edition)

- ↑ "Economic forecasts" (PDF). European Commission – European Commission. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 May 2015.

- ↑ "Republic of Croatia and the IMF".

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ferić, Dražen; Žagmeštar, Hrvoje (28 April 2023). "Pokazatelji siromaštva i socijalne isključenosti u 2022" [Indicators of poverty and social exclusion in 2022]. Priopćenje (in Croatian and English). Zagreb: Državni zavod za statistiku. ISSN 1334-0557. Retrieved 7 January 2024.

- ↑ "Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income – EU-SILC survey". ec.europa.eu. Eurostat. Retrieved 7 January 2024.

- ↑ "Human Development Index (HDI)". hdr.undp.org. HDRO (Human Development Report Office) United Nations Development Programme. Retrieved 12 October 2022.

- ↑ Nations, United. "Inequality-adjusted HDI (IHDI)". hdr.undp.org. UNDP. Retrieved 12 October 2022.

- 1 2 "Aktivno stanovništvo u Republici Hrvatskoj u 2022. – prosjek godine". DZS. Retrieved 7 January 2024.

- ↑ "Statistički centar HZZ-a - Hrvatski zavod za zapošljavanje". Hzz.hr. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ↑ "Unemployment by sex and age – monthly average". appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu. Eurostat. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ↑ Aaron O'Neill (12 January 2022). "Croatia - youth unemployment rate 1999-2019". Statista. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ↑ "Youth unemployment rate by sex, age (15–24) and country of birth". appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu. Eurostat. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- 1 2 https://podaci.dzs.hr/media/n5xaee2t/rad-2023-1-1_3-average-monthly-net-and-gross-earnings-of-persons-in-paid-employment-2023.pdf AVERAGE MONTHLY NET AND GROSS EARNINGS OF PERSONS IN PAID EMPLOYMENT FOR MARCH 2023]

- ↑ "Ease of Doing Business in Croatia". Doingbusiness.org. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 Žderić, Boro; Drempetić, Dubravka (29 May 2023). "Robna razmjena Republike Hrvatske s inozemstvom u 2022" [Merchandise exchange of the Republic of Croatia with foreign countries in 2022]. Priopćenje (in Croatian and English). Zagreb: Državni zavod za statistiku. ISSN 1334-0557. Retrieved 7 January 2024.

- 1 2 3 4 "Main macroeconomic indicators - HNB".

- ↑ "General government debt statistics for September 2022". www.hnb.hr. Retrieved 18 February 2023.}} | revenue = 46.4% of GDP (2021)

- ↑ "Euro area government deficit at 5.1% and EU at 4.7% of GDP". Eurostat. European Commission. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ↑ "Country and Lending Groups". World Bank. Archived from the original on 11 January 2018. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- ↑ "World Economic Situation and Prospects report 2019" (PDF). UN. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 February 2019. Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- ↑ "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2023". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. 10 October 2023. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- ↑ "WEO Database, October 2023. Report for Selected Countries and Subjects: World, European Union". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. 10 October 2023. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- ↑ "Sub-national HDI - Area Database - Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ↑ "Croatia". World Economics. Retrieved 20 December 2023.

- ↑ "Croatia - Market Overview". International Trade Administration. 4 December 2023. Retrieved 20 December 2023.

- ↑ "Doing Business 2020: Croatia Country Profile" (PDF). World Bank Group. 1 January 2020. Retrieved 20 December 2023.

- ↑ "Croatian Economy: Be Dynamic, Not Only in Tourism". IMF. Retrieved 20 December 2023.

- ↑ "GDP growth (annual %) - Central Europe and the Baltics | Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 26 November 2021.

- ↑ "U 2021. godini Hrvatsku posjetilo gotovo 14 milijuna turista". Hrvatska turistička Zajednica (in Croatian). Croatian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- ↑ Orsini, Kristina; Ostojić, Vukašin. "Croatia's Tourism Industry: Beyond the Sun and Sea" (PDF). European Commission. European Union. Retrieved 18 September 2021.

- ↑ "Croatian island eyes green energy self-sufficiency in this decade". Reuters. Reuters. 18 June 2021. Retrieved 26 November 2021.

- ↑ "Croatia - Renewable Energy". www.trade.gov. Retrieved 26 November 2021.

- 1 2 "Nova EU direktiva: Minimalac bi mogao porasti na 4000 kuna, sindikati traže 5000". tportal.hr. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- 1 2 "Overview". World Bank. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ↑ Mariann Nagy – Croatia in the Economic Structure of the Habsburg Empire in the Light of the 1857 Census, p. 81-82

- ↑ Mariann Nagy – Croatia in the Economic Structure of the Habsburg Empire in the Light of the 1857 Census, p. 88

- ↑ Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge: The Penny Cyclopaedia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, vol 22, p. 100-101

- ↑ Mikulas Teich, Roy Porter: The Industrial Revolution in National Context: Europe and the USA, Cambridge University Press, 1996, p. 310

- ↑ Mikulas Teich, Roy Porter: The Industrial Revolution in National Context: Europe and the USA, Cambridge University Press, 1996, p. 311

- ↑ Tanner, Marcus (2001). Croatia: a nation forged in war (2nd ed.). New Haven; London: Yale University Press. p. 110. ISBN 0-300-09125-7.

- 1 2 3 Richard C. Frucht: Eastern Europe: An Introduction to the People, Land, and Culture, p. 462–463

- ↑ The First Yugoslavia: Search for a Viable Political System, Hoover Press, 1983, p. 72

- ↑ Rory Yeomans:Visions of Annihilation: The Ustasha Regime and the Cultural Politics of Fascism, 1941–1945, University of Pittsburgh Pre, 2013, p. 197

- ↑ Hrvoje Matković: Povijest nezavisne države Hrvatske, Drugo, dopunjeno izdanje Zagreb, 2002., p. 118

- ↑ Jozo Tomašević: Rat i revolucija u Jugoslaviji 1941–1945, 2010, p. 785

- ↑ "UNdata | record view | per capita GDP at current prices - US dollars".

- ↑ "Yugoslavia (former) Guest Workers – Flags, Maps, Economy, History, Climate, Natural Resources, Current Issues, International Agreements, Population, Social Statistics, Political System". www.photius.com.

- ↑ Ivo Nejašmić: Hrvatski građani na radu u inozemstvu: razmatranje popisnih podataka 1971, 1981. i 1991.

- ↑ Europa Publications Limited. Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States 1999: 1999. Routledge, 1999. (pg. 279)

- 1 2 3 International Business Publications: Croatia Investment and Trade Laws and Regulations Handbook, p. 22

- ↑ "CIA – The World Factbook 2000 – Croatia". www.iiasa.ac.at.

- 1 2 3 4 Istvan Benczes: Deficit and Debt in Transition: The Political Economy of Public Finances in Central and Eastern Europe, Central European University Press, 2014, p. 203

- ↑ Eastern Europe: An Introduction to the People, Land, and Culture, p. 473

- 1 2 Istvan Benczes: Deficit and Debt in Transition: The Political Economy of Public Finances in Central and Eastern Europe, Central European University Press, 2014, p. 205-206

- ↑ OECD: Agricultural Policies in Emerging and Transition Economies 1999, p. 43

- 1 2 "United Nations Statistics Division – National Accounts". unstats.un.org.

- 1 2 Gale Research: Countries of the World and Their Leaders: Yearbook 2001, p. 456

- ↑ Istvan Benczes:Deficit and Debt in Transition: The Political Economy of Public Finances in Central and Eastern Europe, Central European University Press, 2014, p. 207

- ↑ "Croatia". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. 2 March 2022. (Archived 2022 edition)

- ↑ Richard C. Frucht: Eastern Europe: An Introduction to the People, Land, and Culture, p. 468

- 1 2 Adams, John. "The Political Economies of Slovenia and Croatia: Does EU and Eurozone Membership Play a Role At All?" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 July 2014. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- 1 2 "Data services - Eurostat". ec.europa.eu.

- ↑ "qfinance.com". www.qfinance.com. Archived from the original on 9 February 2013. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- 1 2 "Croatia Economy: Population, GDP, Inflation, Business, Trade, FDI, Corruption". The Heritage Foundation.

- 1 2 Martina Dalić (2013): "Croatia: A Prolonged Crisis without Recovery" in Novotny Vitt (ed.) From Reform to Growth: Managing the Economic Crisis in Europe, Centre for European Studies, Brussels, May/2013, p. 67-88

- ↑ "Economic Outlook Darkens in Croatia :: Balkan Insight". www.balkaninsight.com. 29 August 2012.

- ↑ "Ekonomski Indikatori". Archived from the original on 28 September 2007.

- ↑ "Državni Zavod Za Statistiku – Republika Hrvatska". www.dzs.hr.

- ↑ "Pokazatelji Siromaštva u 2010/Poverty Indicators, 2010". www.dzs.hr.

- ↑ "Fitch Cheers Croatia With Upbeat Rating :: Balkan Insight". www.balkaninsight.com. 6 September 2012.

- ↑ "Statistics Explained". epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu.

- ↑ List of countries in Europe by monthly average wage

- ↑ "Croatia GDP Growth Quickens In Q4, 28 February 2017, accessed 14 March 2017".

- ↑ "Croatia Trade Deficit Narrows In September". RTTNews.

- ↑ "Jasmina Kuzmanovic, Croatia to Narrow 2016 Budget Deficit on Planned Economic Growth, 10 March 2016, accessed 14 March 2017". Bloomberg News. 10 March 2016.

- ↑ "Croatia views Moody's outlook upgrade as results of reform: minister, 11 March 2017, accessed 14 March 2017". 21 March 2014.

- ↑ "Autumn 2020 Economic Forecast". European Commission - European Commission. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- ↑ "European Commission revises up Croatia's 2021 GDP forecast to 5.4 pct". N1 (in Croatian). 7 July 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ↑ "EU Commission raises forecast for Croatia's 2021 GDP growth to 8.1%". seenews.com. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ↑ "Fitch Upgrades Croatia to 'BBB'; Outlook Positive". www.fitchratings.com. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ↑ "Izvoz porastao za 24,9 posto, uvoz za 20,6. Razlika je još uvijek velika na strani uvoza". Novi list. 9 November 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ↑ "Rekordna godina: Skor iz 2019. nadmašen za 2 milijarde eura". Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ↑ Trkanjec, Zeljko (15 November 2021). "Fitch assigns Croatia highest credit rating in history". www.euractiv.com. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ↑ "Fitch Upgrades Croatia to 'BBB'". Invest Croatia. 15 November 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ↑ "Croatia's eurosceptics fail in bid on referendum to block euro". SWI swissinfo.ch. Archived from the original on 17 November 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ↑ Trkanjec, Zeljko (1 February 2022). "Industrial production in Croatia up 6.7% in 2021". www.euractiv.com. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- ↑ "CROATIAN BUREAU OF STATISTICS". www.dzs.hr. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- ↑ "Industrijska proizvodnja u 2021. godini porasla 6,7 posto". tportal.hr. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- ↑ "Why Rimac-Bugatti CEO plans to keep pushing boundaries". Automotive News Europe. 20 August 2021. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

- ↑ "Bugatti Rimac $310 million Croatian headquarters under construction". CarExpert. 17 November 2021. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

- ↑ "Rimac breaks ground on new Croatian HQ, complete with a track". Motor1.com. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

- ↑ "Industrial Workers Statistics in February Shows Rise m-o-m And Fall y-o-y". www.total-croatia-news.com. 2 April 2022. Archived from the original on 3 April 2022. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ↑ "Croatia's February Industrial Production Up 4%". www.total-croatia-news.com. 31 March 2022. Archived from the original on 3 April 2022. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ↑ "Croatia's tourism revenue expected to reach record high this year-Xinhua". english.news.cn. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ↑ "EBRD more than doubles forecast of Croatia's GDP growth". N1 (in Croatian). 28 September 2022. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ↑ PoslovniPuls (11 October 2022). "Podaci DZS-a: Izvoz raste impresivno, ali uvoz još više". PoslovniPuls (in Croatian). Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ↑ "Government of the Republic of Croatia - Tourism figures indicate higher-than-forecast economic growth". vlada.gov.hr. Retrieved 16 October 2022.

- ↑ "EBRD lifts Croatia's 2022 GDP fcast to 6.5%, cuts 2023 projection". seenews.com. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ↑ "Jutarnji list - Pfizer u Hrvatskoj gradi tvornicu vrijednu 100 milijuna eura: Proizvodit će biološke lijekove za rijetke bolesti". novac.jutarnji.hr (in Croatian). 10 June 2022. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ↑ "Croatia's IT sector boosts revenue 3.3% to 27.8 bln kuna (3.7 bln euro) in 2020". seenews.com. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ↑ Stojkovski, Bojan (30 September 2022). "The Top 10 IT Companies in Croatia in 2022". TheRecursive.com. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ↑ "McKinsey: Croatia's digital economy might reach 15 pct of GDP by 2030". N1 (in Croatian). 14 September 2022. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ↑ "Croatia's recovery and resilience plan". commission.europa.eu.

- ↑ Hughes, Rebecca Ann (12 July 2022). "As Croatia joins the euro, which 7 EU countries still use their own currency?". Euronews. Retrieved 21 November 2022.

- ↑ Blenkinsop, Philip (12 July 2022). "'Amazing journey': EU accepts Croatia as 20th euro zone member". Reuters. Retrieved 21 November 2022.

- ↑ Pajić, Darko (16 September 2022). "Minimalna plaća će porasti na 4000 kuna, sindikati traže više: "To je premalo, mora biti veća od 700 eura"". Novi list. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ↑ "Plenković: Povećat ćemo minimalnu plaću, a EK smo poslali zahtjev za uplatu 700 mil. eura". www.vecernji.hr (in Croatian). Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ↑ "Minimalna plaća mogla bi rasti na 4 tisuće kuna. Sindikati traže pet tisuća". NACIONAL.HR (in Croatian). Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ↑ "Industry Breakdown of Companies in Croatia". HitHorizons.

- ↑ Pili, Tomislav; Verković, Davor (1 October 2011). "Iako čini gotovo petinu BDP-a, i dalje niskoprofitabilna grana domaće privrede" [Even though it comprises nearly a fifth of the GDP, it is still a low-profit branch of the national economy]. Vjesnik (in Croatian). Archived from the original on 14 June 2012. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- ↑ "Turistički prihod porast će prvi put nakon 2008" [Tourist income to rise for the first time since 2008]. t-portal.hr (in Croatian). T-Hrvatski Telekom. 14 September 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ↑ "History of Opatija". Opatija Tourist Board. Archived from the original on 29 April 2012. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ↑ "Activities and attractions". Croatian National Tourist Board. Archived from the original on 3 April 2016. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ↑ "OUR NUMBERS - ALL BLUE FLAG AWARDED SITES PER COUNTRY 2021". Blue Flag. Foundation for Environmental Education. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ↑ "UNWTO World Tourism Barometer" (PDF). October 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 September 2013. Retrieved 23 April 2008.

- ↑ "Croatian highlights, Croatia". Euro-poi.com. Archived from the original on 24 February 2013. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ↑ "poljoprivredna" (PDF) (in Croatian). Ministarstvo poljoprivrede. 2021. Retrieved 18 February 2023.

- ↑ "Popis poljoprivrede 2020" (PDF) (in Croatian). Ministarstvo poljoprivrede. 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2023.

- ↑ Predrag, Cvjetićanin; Kanižaj, Željko (31 January 2023). "Površina i proizvodnja žitarica i ostalih usjeva u 2022" [Area and production of cereals and other crops in 2022]. DZS (in Croatian). Zagreb. ISSN 1334-0557. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ↑ "Croatia production in 2018, by FAO".

- 1 2 3 Tanja Poletan Jugović (11 April 2006). "The integration of the Republic of Croatia into the Pan-European transport corridor network". Pomorstvo. University of Rijeka, Faculty of Maritime Studies. 20 (1): 49–65. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- ↑ "Ključne brojke 2020" [Key figures 2020] (PDF) (in Croatian and English). HUKA. August 2021. ISSN 1848-0233. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 November 2021. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "Traffic counting on the roadways of Croatia in 2009 – digest" (PDF). Hrvatske ceste. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ↑ "EuroTest". Eurotestmobility.com. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 3 January 2009.

- ↑ "Brinje Tunnel Best European Tunnel". Javno.com. Archived from the original on 15 January 2009. Retrieved 3 January 2009.

- ↑ Pili, Tomislav (10 May 2011). "Skuplje korištenje pruga uništava HŽ" [More Expensive Railway Fees Ruin Croatian Railways]. Vjesnik (in Croatian). Archived from the original on 14 June 2012. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- ↑ "Air transport". Ministry of the Sea, Transport and Infrastructure (Croatia). Archived from the original on 3 July 2016. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

- ↑ "FAA Raises Safety Rating for Croatia". Federal Aviation Administration. 26 January 2011. Archived from the original on 26 June 2013. Retrieved 27 January 2011.

- ↑ "Riječka luka –jadranski "prolaz" prema Europi" [The Port of Rijeka – Adriatic "gateway" to Europe] (in Croatian). World Bank. 3 March 2006. Archived from the original on 5 August 2012. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- ↑ "Luke" [Ports] (in Croatian). Ministry of the Sea, Transport and Infrastructure (Croatia). Archived from the original on 16 December 2012. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- ↑ "Plovidbeni red za 2011. godinu" [Sailing Schedule for Year 2011] (in Croatian). Agencija za obalni linijski pomorski promet. Archived from the original on 15 July 2011. Retrieved 27 August 2011.

- ↑ "The JANAF system". JANAF. Jadranski naftovod. Retrieved 5 January 2023.

- ↑ "Transportni sustav" [Transport system]. Plinacro (in Croatian). Retrieved 5 January 2023.

- 1 2 "Izvori energije" [Energy sources]. HEP Opskrba (in Croatian). Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- 1 2 "Energetska statistika u 2022" [Energy statistics, 2022] (PDF). Statistička izvješća (in Croatian). Zagreb: Croatian Bureau of Statistics: 17. 15 December 2023. ISSN 1334-5834.

- ↑ "Energetska statistika u 2022" [Energy statistics, 2022] (PDF). Statistička izvješća (in Croatian). Zagreb: Croatian Bureau of Statistics: 15. 15 December 2023. ISSN 1334-5834.

- 1 2 "Energija u Hrvatskoj 2021" (PDF). Energetski institut Hrvoje Požar (in Croatian and English). Ministry of Economy and Sustainable Development, Republic of Croatia. ISSN 1848-1787. Retrieved 2 November 2023.

- 1 2 "Državni proračun Republike Hrvatske za 2024. godinu i projekcije za 2025. i 2026. godinu" [State Budget of the Republic of Croatia for 2024 and projections for 2025 and 2026]. Narodne novine (in Croatian). 14 December 2023. Retrieved 15 January 2024.

- ↑ "IMF TREND 1980 - 2027" [IMF TREND 1980 - 2027]. DZS. IMF. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- 1 2 "Gross domestic product - Review by countries 2000-2018". dzs.hr. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

External links

![]() Media related to Economy of Croatia at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Economy of Croatia at Wikimedia Commons

.JPG.webp)

.jpg.webp)