Dinu Brătianu | |

|---|---|

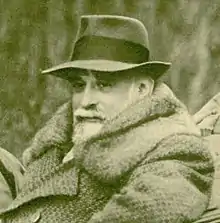

Constantin I.C. Brătianu on a hunt (December, 1932) | |

| Minister of Finance | |

| In office 14 November 1933 – 3 January 1934 | |

| Prime Minister | Ion G. Duca Constantin Angelescu |

| Preceded by | Virgil Madgearu |

| Succeeded by | Victor Slăvescu |

| Minister Secretary of State | |

| In office 23 August 1944 – 3 November 1944 | |

| Prime Minister | Constantin Sănătescu |

| Preceded by | Mihai Antonescu |

| Leader of the National Liberal Party | |

| In office 4 January 1934 – November 1947 | |

| Preceded by | Ion G. Duca |

| Succeeded by | Party dissolved |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Constantin I. C. Brătianu January 13, 1866 Ștefănești, Argeș County, United Principalities |

| Died | August 20, 1950 (aged 84) Sighet Prison, People's Republic of Romania |

| Resting place | Florica Church, Ștefănești, Argeș County |

| Political party | National Liberal Party |

| Spouse |

Alexandrina Brătianu (née Costinescu)

(m. 1907–1950) |

| Children | 3 |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives | Ion I. C. Brătianu, Vintilă Brătianu (brothers) |

| Alma mater | Polytechnic University of Bucharest École nationale supérieure des mines de Paris |

| Occupation | Engineer, politician |

Dinu Brătianu (January 13, 1866 – August 20, 1950), born Constantin I. C. Brătianu, was a Romanian engineer and politician who led the National Liberal Party (PNL) starting in 1934.

Life

Early career

He was born at the estate of Florica, in Ștefănești, Argeș County, the son of the great Romanian statesman Ion Brătianu and of his wife, Pia Brătianu (née Pleșoianu). The fourth of five children, his brothers were Ion I. C. Brătianu and Vintilă Brătianu.[1] Dinu Brătianu attended Saint Sava High School in Bucharest, while also taking private lessons with the mathematicians Spiru Haret and David Emmanuel. He then studied engineering at the Bucharest Polytechnic, graduating in 1890, and then pursued his studies at the École des mines in Paris.[1]

Upon returning to Romania, he worked on the coordination of oil field exploitation works in Solonț, Bacău County. He took part in the installation of the first wells in Moinești, in the construction of the railway that was mounted on Tarcău River valley, and of the railway bridges between Barboși and Brăila.[2] He later was the director of the Romanian Bank, the most important private bank in the country at the time, and several other credit unions.[3]

Brătianu was first elected to the Chamber of Deputies of Romania in 1895, and was elected without interruption between 1910 and 1938. He held no governmental position until 1933–1934, when he was Minister of Finance.

Under Carol and Antonescu

After the assassination of Prime Minister Ion G. Duca by the Iron Guard (December, 1933), he became head of the PNL. During the interwar period, he became active in opposing the authoritarian regime of King Carol II and his Prime Minister Gheorghe Tătărescu.

After Carol's abdication and the fascist regime known as the National Legionary State, Brătianu offered his support to dictator Ion Antonescu, given that the latter's close relation with Nazi Germany had helped Romania win back territories it had lost to the Soviet Union (Bessarabia, Northern Bukovina, and the Hertsa region), taken back through World War II's Operation Barbarossa. The heavy losses inflicted on the Romanian troops and the successful offensives of the Red Army made Brătianu favor King Michael's plan to align Romania with the Allies.

Post–1945

After the August 23, 1944 Royal Coup, he was Minister without portfolio in two successive cabinets of Constantin Sănătescu. As leader of the PNL, he was unable to slow down the accession of Romanian Communist Party to power, as the appeal of his party had suffered major blows due to Brătianu's sympathy towards Antonescu.

He sought to oppose the communists by protesting to the American and British diplomats from Bucharest. Cortlandt Van Rensselaer Schuyler, the American general, portrayed the man who was supposed to fight communists: "Generally, Mr. Brătianu has disappointed me as a political leader", Schuyler wrote in 1945. "He is almost 80 and seems to be wasting his energy. Although he is very unhappy about the actual state of things, he has not offered a constructive programme for recovery, aside from a general opposition to what he calls the exorbitant and unjust demands set by Russia".

He refused to be part of the communist cabinet formed by Petru Groza on March 6, 1945. The Siguranța (the secret police service, which by that time had been taken over by the communists) had him under close surveillance.[4] Kept under house arrest by the authorities, Brătianu was arrested in 1950 and imprisoned without trial. On May 5, 1950 he was sent to the notorious Sighet Prison, where he died a few months later, on August 20, in cell number 12. He was buried in an unmarked grave in the nearby Pauper's Cemetery, Sighetu Marmației. In the fall of 1971, his remains were reburied in a niche in the inner wall of the church in his birthplace, Florica.[2]

Private life and legacy

_I.C._Bratianu%252C_pe_Calea_Dorobantilor_nr._16%252C_Bucuresti%252C_sect._1.JPG.webp)

On August 26, 1907, he married Alexandrina (Adina) Costinescu (1886–1975), the daughter of Emil Costinescu, an important National Liberal Party politician.[3][5] In 1909, Brătianu had his residence built at 16, Calea Dorobanților, near Piața Romană in Bucharest; the architect was Petre Antonescu.[3][6] During World War I, when Brătianu took refuge in Iași with his family, the mansion was pillaged by the Central Powers troops that had occupied Bucharest in December 1916.[1]

A high school in Ștefănești, Argeș bears his name.[7]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Dumitriu, Mircea (January 13, 2007). "Constantin (Dinu) I.C. Brătianu și lumea Brătienilor". România liberă (in Romanian). Retrieved May 13, 2023.

- 1 2 Grigorescu, Denis (August 9, 2018). "Povestea dureroasă a lui Constantin Dinu Brătianu, fost ministru în patru guverne îngropat de comuniști fără nume și cruce". Adevărul (in Romanian). Retrieved May 12, 2023.

- 1 2 3 Stan, Simina (October 26, 2006). "Amintiri pe Calea Dorobanților". Jurnalul Național (in Romanian). Retrieved May 13, 2023.

- ↑ Pelin, Mihai (October 6, 2005). "Un om al trecutului, rătăcit intr-o lume brutală". Jurnalul Național (in Romanian). Retrieved May 14, 2023.

- ↑ Bălăican, Delia (April 2021). "Adina Brătianu: "Aici trecem dintr-o frumusețe într-alta". Carte poștală din Italia anilor 1924 și 1926". Orizonturi culturale italo-române (in Romanian). XI (4).

- ↑ Diamandi, Ion (November 7, 2022). "Casa Dinu Brătianu, o casă elegantă în stil eclectic". Life and Style (in Romanian). Retrieved May 13, 2023.

- ↑ "Liceul Tehnologic "Dinu Brătianu", Ștefănești, Argeș". www.liceulstefanesti.ro (in Romanian). Retrieved May 13, 2023.