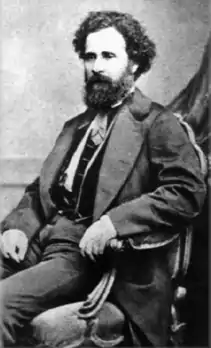

Ion C. Brătianu | |

|---|---|

| |

| Prime Minister of Romania | |

| In office July 24, 1876—April 9, 1881 June 9, 1881 – March 20, 1888 | |

| Preceded by | Nicolae Golescu Manolache Costache Epureanu Dimitrie Brătianu |

| Succeeded by | Dimitrie Ghica Dimitrie Brătianu Theodor Rosetti |

| Personal details | |

| Born | June 2, 1821 Argeș County, Wallachia |

| Died | May 16, 1891 (aged 69) Kingdom of Romania |

| Political party | National Liberal Party |

Ion Constantin Brătianu (Romanian pronunciation: [iˈon brətiˈanu]; June 2, 1821 – May 16, 1891) was one of the major political figures of 19th-century Romania. He was the son of Dincă Brătianu and the younger brother of Dimitrie, as well as the father of Ionel, Dinu, and Vintilă Brătianu. He also was the grandfather of poet Ion Pillat.

Biography

Early life

Born to wealthy Argeș boyars in Pitești, Principality of Wallachia, he entered the Wallachian Army in 1838, and in 1841 started studying in Paris. Returning to his native land, Brătianu took part, with his friend C. A. Rosetti and other young politicians (including his brother), in the 1848 Wallachian Revolution, and acted as prefect of the police in the provisional government formed in that year.[1]

The restoration of Imperial Russian and Ottoman authority shortly afterwards drove him into exile. He took refuge to Paris, and endeavoured to influence French opinion in favor of the proposed union and autonomy of the Romanian Danubian Principalities. In 1854, however, he was sentenced to a fine and three months' imprisonment for sedition, and later confined in a lunatic asylum; in 1856, he returned to Wallachia with his brother – afterwards one of his foremost political opponents.[1]

Under Cuza and in the opposition

He was in favor of the Danubian Principalities' (Wallachia's and Moldavia) union, as a member of Partida Națională. During the reign of Alexander Ioan Cuza (1859–1866), Brătianu founded (in 1875) the National Liberal Party (PNL), until today a major political formation. Opposition to the land reform united the emerging Liberals and Conservatives against the Domnitor and his inner circle. Both parties comprised mainly landowners, and allied to block legislation in the Chamber – causing Cuza to impose his authoritarian government in May 1864. The two-party coalition, remembered as the monstrous coalition, opted for the removal of Cuza. Brătianu took part in the deposition of 1866 and in the subsequent election of Prince Carol of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, under whom he held several ministerial appointments throughout the next four years.

Nonetheless, his very sinuous relationship with the new Prince was the source of several crisis situations. Notably, Brătianu would point to the benefits of a Republican project (which Rosetti and his left wing of the Liberal Party had never ceased advocating). Thus, when the experimental Republic of Ploiești was created in 1870 around a Liberal group, Ion Brătianu was arrested as the inspirational figure, but was soon released.

In 1871, the Liberals organized protests in favor of France – just defeated in the Franco-Prussian War – and implicitly against German Empire, the Conservatives, and Prince Carol himself. The weight of the moment showed the weaknesses of the Liberals, as well as Carol's resolution: the Prince called on Lascăr Catargiu to form a stable and reliable government. The change in tactics forced the Liberals to form their loose tendency as a real Party in 1875. Alongside several liberal tenets, the new formation took a further step towards advocating protectionism and persecution of Jewish Romanians (see History of the Jews in Romania). In 1876, aided by C. A. Rosetti, Brătianu formed a Liberal cabinet, which remained in power until 1888 - this marked his coming to terms with Carol.

Prominence

The government took steps at taking the country out of its Ottoman vassalage; however, it differed from Conservatives in that they saw the main threat posed to Romania in Austria-Hungary. Liberals were of the generation that had truly brought Romanians in Transylvania to the country's attention; on the other hand, Catargiu had signed an agreement with the Austrian Monarchy that awarded it commercial privilege in Romania – while quieting its suspicion towards Romanian irredentism. Brătianu's government did not disturb this climate after the Russian alliance proved unsatisfactory, and the two parties resorted to assisting Romanian cultural ventures in Transylvania (until World War I).

He aligned the country with Russia as soon as the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878 began – with its chapter, the Romanian War of Independence. While Romania did emancipate itself from Ottoman tutelage, Brătianu had to accommodate a prolonged Russian occupation, and the Congress of Berlin saw Russia seizing Southern Bessarabia, the only part of Bessarabia still under Romanian control (Romania was awarded Northern Dobruja in return). After the war, the Principality of Bulgaria appeared and began a search for a prince. According to Nikolay Pavlovich Ignatyev, Brătianu supported the election of Prince Carol I as monarch of Bulgaria. Ignatyev said the intention of the Romanian officials was to establish a personal union with Bulgaria.[2] In 1881, Romania proclaimed itself a Kingdom.

The Congress also pressured the Liberals to discard the discrimination policies, and the government agreed to allow Jews and Dobrujan Muslims to apply for citizenship (with a 10-year probation), but continued forbidding foreign-born people or non-citizens from owning land. However, he had anti-Semitic views, publishing a lot of discriminatory laws, being responsible for the exile of various Jewish Romanian intellectuals.[3][4][5] The most famous Jewish intellectual exiled by Brătianu was Moses Gaster, at the initiative of Dimitrie A. Sturdza.[6]

The Brătianu government introduced most modern reforms in the administrative, educational, economical, and military fields. It celebrated its main success in 1883, when the Liberals managed to have the 1866 Constitution of Romania amended – enlarging the number of electors and establishing a third electoral college, one that gave some representation to peasants and the urban employees. The move was not radical, and it served to obtain the Liberals political ascendancy: the very first elections under the new law brought them an overwhelming majority.

In 1886, after a meeting with Carol I and the Bulgarian prince Alexander of Battenberg, Brătianu informed the Bulgarian diplomat Grigor Nachovich that Alexander had requested a Balkan confederation under the leadership of Carol I. This turned out to be a misunderstanding.[2]

After 1883 Brătianu acted as sole leader of the party, owing to a quarrel with Rosetti, his friend and political ally for nearly forty years. His long tenure of office, without parallel in Romanian history, rendered Brătianu extremely unpopular, and at its close his impeachment appeared inevitable. But any proceedings taken against the minister would have involved charges against the king, who was largely responsible for his policy, and the impeachment was averted by a vote of parliament in February 1890.[1]

Other activities

Besides being the leading statesman of Romania during the critical years 1876–1888, Brătianu attained some eminence as a writer. His French language political pamphlets, Mémoire sur l'empire d'Autriche dans la question d'Orient ("Account of the Austrian Empire in the Oriental Issue", 1855), Réflexions sur la situation ("Musings on the Situation", 1856), Mémoire sur la situation de la Moldavie depuis le traité de Paris ("Account on Moldavia's Situation After the Treaty of Paris", 1857), and La Question religieuse en Roumanie ("The Religious Issue in Romania", 1866), were all published in Paris.[1]

In memoriam

Many places, schools, streets, etc. in Romania are named after him, including:

- The commune I. C. Brătianu in Tulcea County.

- The Ion C. Brătianu National College in Pitești.

- The I.C. Brătianu National College in Hațeg.

- The Ion C. Brătianu Boulevard in downtown Bucharest.

- I. C. Brătianu Plaza in Timișoara.

- The Mihail Kogălniceanu-class river monitor, Ion C. Brătianu (F-46).

References

- 1 2 3 4 Chisholm 1911.

- 1 2 Nyagulov, Blagovest (2012). "Ideas of federation and personal union with regard to Bulgaria and Romania". Bulgarian Historical Review (3–4): 36–61. ISSN 0204-8906.

- ↑ https://www.yadvashem.org/yv/pdf-drupal/en/report/romanian/1.1_Roots_of_Romanian_Antisemitism.pdf

- ↑ Bogdan, Caranfilof. "(PDF) "Iuda sub vremuri". O contribuție la istoria antisemitismului românesc | Caranfilof Bogdan - Academia.edu".

- ↑ "State, Modernity and Anti-Semitism in Ion C. Bratianu's Political Speeches from the Second Half of the Nineteenth Century". Cogito - Multidisciplinary Research Journal (4): 17–28. 2018.

- ↑ Manolescu, Nicolae (September 12, 2014). "Moses Gaster, o figură pe nedrept uitată". Adevărul (in Romanian). Retrieved December 24, 2021.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Bratianu, Ion C.". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 4 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 436.

- Keith Hitchins, România 1866–1947, Bucharest, Humanitas, 2004

- Stevan K. Pavlowitch, A History of The Balkans 1804–1945, Addison Wesley Longman Ltd., 1999

.svg.png.webp)