In ancient Egypt, there is evidence of conspiracies within the royal palace to put the reigning monarch to death. Texts are generally silent on the subject of struggles for influence, but a few historical sources, either indirect or very eloquent, depict a royal family disunited and agitated by petty grudges. Highly polygamous, Pharaoh had numerous concubines living in the harem buildings. At certain points in history, women driven by ambition and jealousy formed cabals ready to sacrifice the general interest for the particular needs of princes and courtiers in need of recognition. In the most serious cases, these factions manifested themselves by fomenting conspiracies that threatened or even shortened the life of the sovereign – all to the hoped-for benefit of a secondary wife and her eldest son in competition with the more legitimate Great Royal Wife.

During the Old Kingdom, the 6th Dynasty experienced several similar incidents. According to the historian Manetho, Pharaoh Teti was assassinated by his bodyguards. A vast campaign of damnatio memoriae revealed by archaeology seems to confirm this claim. More wary, Pepi I escaped a plot which, as Judge Ouni reports, was fomented by a royal wife. As for Queen Nitocris, according to a legend recounted by Herodotus, she avenged the assassination of her brother Merenre II by drowning the conspirators. During the Middle Kingdom, the plot that ended the life of Amenemhat I is documented in two important literary texts, the Instructions of King Amenemhat to his Son and the Story of Sinuhe. Both clearly show the involvement of the royal entourage, including bodyguards, harem wives and royal sons. All seem to have been deeply resentful of Senusret I, the legitimate heir.

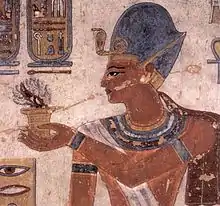

During the New Kingdom, the end of the 18th Dynasty was marked by the murder of Zannanza-Smenkhkare and the possible elimination of Prince Nakhtmin by Horemheb. In the nineteenth dynasty, contrary to what was once thought, Rameses II did not ascend the throne by eliminating a rival elder brother. It is possible, however, that he may have had to fear the actions of general Mehy, a close adviser to his father, Pharaoh Seti I. After Merenptah's death, the Ramesside family was torn apart by a series of conspiracies over the next fifteen years: Amenmes tried to overthrow his half-brother Seti II, the chancellor Bay placed the puppet king Siptah on the throne, and queen Twosret had Bay eliminated before being eliminated herself by the old general Sethnakht, the founder of the 20th dynasty. Restorer of order, Ramses III, after thirty-two years of reign, had his throat slit in a conspiracy born in the mind of Queen Tiye. As the Judicial Papyrus of Turin reveals, some thirty courtiers were involved in the affair, including harem administrators, soldiers, priests and magicians. The conspiracy failed in its main objective, however, and Prince Pentawer was unable to oust Ramesses IV, the designated successor.

Written sources

Egyptian lexicon

The term "conspiracy" and its quasi-synonyms "plot" and " conjuration" refer to a secret agreement between several people, with a view to overthrowing an established power (a government) or with a view to attacking the life of a person in authority (head of state, minister).[1] In the Egyptian language, the terms covering this notion of nefarious agreement are iret sema "to make a conjuration", semayt "enemy of the gods", iret sebjou "to make rebellion (against Pharaoh or the gods)" and oua "to meditate, ourdir, hold a conciliabule, plot".[2][3]

| Transcription | Hieroglyph | Translation | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| oua | scheming, plotting | |||||||||

| ouat | villains | |||||||||

| ouatou | plotters | |||||||||

| sebit | rebellion | |||||||||

| sebi | rebel | |||||||||

| semayt | group, troop, band | |||||||||

| sema | to kill, to murder | |||||||||

| semat | murderer |

Egyptian texts

.jpg.webp)

According to Egyptian texts alone, the number of pharaohs assassinated in a conspiracy is extremely slim: Amenemhat I in the 12th Dynasty and Ramesses III in the 20th Dynasty, i.e. two of the 345 kings who succeeded each other over a 3,000-year period. The death of the former is documented in the Instructions of King Amenemhat to his Son, a piece of wisdom in which the deceased king addresses his son Senusret I from the afterlife. The text is known from several copies, the earliest of which date back to the 18th dynasty (Milligen papyrus, Sallier II papyrus). The text was commissioned from the scribe Khety shortly after Sesostris's enthronement. Now a classic of royal ideology, the text is also known from schoolchildren's – very faulty – works on ostracon up to the 30th Dynasty.[4] Another literary classic, the Story of Sinueh, is known from several papyri and ostraca dating from the 12th to the 20th dynasties. The conspiracy is evoked at the start of the plot when the hero overhears a conversation between two plotters. Panic-stricken, he flees the country for fear of being considered an accomplice.[5]

The assassination of Ramesses III, during the plot known as the "Harem Conspiracy", is documented in various contemporary judicial texts. The Lee and Rollin papyri, the Riffaud texts and the Judicial Papyrus of Turin are the main documentary sources. The latter is a list of some thirty conspirators divided into five categories according to their degree of involvement. In all these texts, the phraseology is obscure, as the event – deemed too abominable – is dissolved in the unspoken and in stereotyped, convoluted expressions. The names of the plotters are distorted in a pejorative manner, but their honorific titles show that they were in close contact with the sovereign.[6]

Other testimonials

This very limited number of conspiracies can be augmented by Greek sources, which are not confirmed by Egyptian documents. Herodotus reports that Queen Nitocris took revenge on the conspirators who had murdered her brother (Histories II, 100),[7] implying that Merenre II was also murdered. According to Manetho, King Teti (Othoes) was murdered by his own guards (Ægyptiaca, fr. 20–22).[8] Indirect archaeological evidence suggests that some of Teti's courtiers did indeed take part in a conspiracy; the same is true of Pepi I's entourage. Manetho also reports the assassination of Amenemhat II by his eunuchs (Ægyptiaca, fr. 34–37).[9] There seems to have been a regicide in the 18th dynasty, not of Tutankhamun as some have suggested, but of his obscure predecessor Smenkhkare. The identity of the latter is still debated. He appears to be Prince Zannanza, mentioned in Hittite writings such as the Gesture of Shouppilouliouma and Moursili's Prayer to All the Gods, both of which refer to diplomatic letters exchanged between Emperor Šuppiluliuma and an anonymous Egyptian queen, Akhenaten's widow.[10] Other pharaohs suffered violent deaths without the chronicles mentioning a conspiracy; Narmer during a hunt, Seqenenre Tao during a war, Bakenranef and Apries during conflicts between rival dynasties, Ptolemy XI had his throat cut by an angry crowd and Ptolemy XIV, known as Caesarion, was eliminated by the Roman emperor Augustus.[11]

Mythological background

The issue of regicide

In ancient Egypt, but also in pre-colonial African kingdoms, the issue of regicide had a strong cosmo-mythological background. Among the Moundang of Chad, the king of Léré had to be executed after seven years of reign before he lost his power over meteorological phenomena. Among the Shilluk of the White Nile, the king of Fachoda was executed by his guards on the recommendation of the royal wives when, aging, he could no longer satisfy them sexually. The underlying idea was the fear that, by mimicry, the physical decrepitude of the sovereign would bring about the same fate for the entire nation.[12] In the Osiris myth, an obligatory reference for Pharaonic royalty, King Osiris died in the 28th year of his reign in a plot hatched by his brother Set-Typhon.

Having secretly measured the exact length of Osiris' body, Typhon had a superb and remarkably ornate chest built, and ordered it to be brought to a feast. At the sight of this chest, all the guests were astonished and delighted. Typhon then jokingly promised to make a present of it to whomever, by lying down in it, filled it exactly. One after the other, all the guests tried it on, but none of them found it to their liking. Finally, Osiris entered and stretched himself out on it. At the same moment, all the guests rushed to close the lid (...) Once the operation was completed, the chest was carried up the river and lowered into the sea.

— Plutarch, On Isis and Osiris, excerpts from §. Translation by Mario Meunier[13]

As we know from The Adventures of Horus and Set,[n 1] after the disappearance of Osiris, the main problem was not so much to punish the murderer as to find the best candidate for the Pharaonic office. A divine tribunal presided over by Ra was mandated to resolve the issue. The choice was between Set and Horus. The former, a powerful adult god, possessed stubbornness and physical strength. The second, very young and inexperienced, could only argue that he was the rightful heir son. For many years, the two gods competed for power in jousts and contests. In the end, the court's preference fell on Horus, backed by his father Osiris, who controlled agricultural fertility from the beyond.[14] Three Pharaonic regicides have been well documented: the assassinations of Teti (6th Dynasty), Amenemhat I (12th Dynasty) and Ramses III (20th Dynasty). In all three cases, the rulers were strong, restoring the dynastic order, but old or aging. Amenemhat and Ramses were in their seventies when they died. In the case of the latter, a medical scan of the mummy revealed a severely debilitating heart condition. In all three cases, it is disturbing to note that the plotters perpetrated their murderous deeds at a time when the Pharaoh's sacred aura had been exhausted (around the age of thirty), just before the celebration of the Sed-Festival, which was supposed to regenerate the sovereign and restore his physical and divine vigour.[15]

Rules of succession

A patriarchal society, ancient Egypt gave priority to men as holders of authority, while granting some rights and freedoms to women. At all social levels, from the lowest to the highest, the son hoped to inherit the professional office held by his father. In principle, heirs to the throne had to be sons of the Great Royal Wife (Queen), but, by default, they could also be sons of a secondary wife.[16] The access of a woman to supreme power was unusual, linked to the decay of monarchical power, as in the case of Nitocris and Sobekneferu, or during succession crises linked to consanguinity, as in the cases of Hatshepsut, Neferneferuaten and Twosret.[n 2]

Egyptian royalty did not clearly codify its inheritance rules, but the Osiris myth prevailed: "Let the inheritance be given to the son who buries, according to the law of Pharaoh".[17] Royal funerals were celebrated under the symbolic patronage of Horus, son of Osiris. The son's social role was to maintain the memory of his deceased father by organizing his burial and funeral cult. When transposed to the royal family, the Osiris myth justified succession from father to son. The filial act of Horus (living pharaoh) to Osiris (dead pharaoh) legitimized the succession. So, to establish his authority, every new pharaoh had to attend his predecessor's funeral.[18] Actual genetic descent was therefore of secondary importance. More important was to recognize his predecessor as his ancestor, and to place himself in his lineage by paying him a funeral cult. For example, Pharaoh Ay (sixty at investiture), successor to Tutankhamun (twenty at death), performed the ritual and social role of a son even though he was biologically old enough to be a grandfather.[19]

To become Pharaoh, it was not enough to be crowned as such; it was imperative to preside over a royal funeral. The possession of a corpse for burial was therefore a political necessity.[n 3] So, what better way to get one than to assassinate an old king during a conspiracy, especially when the heir apparent was absent? The assassination of Amenemhat I is a case in point. Wounded in the distance but informed of the conspiracy, Senusret I rushed to the palace where his father's remains laid in order to take over the succession. From that moment on, he never ceased to emphasize his filial ties in his propaganda texts.[20] Much more than written sources suggest, royal succession was also a question of charisma and competition – between princes and/or courtiers. The pharaoh who rallied the greatest number of supporters from within the palace and the provincial administration became pharaoh.[21] It's no coincidence that the remains of Osiris, butchered by Set, were likened to Egypt itself. In reconstituting the body of Osiris, Horus also reconstituted the nation, the forty-two pieces of the body being linked to the forty-two regions of the kingdom.[22]

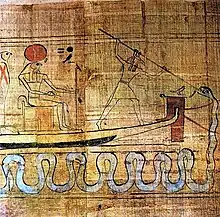

Cosmic foes

According to the belief in divine, immanent justice, evil attracts evil and good attracts good. The gods and ancestors watched over the living and, when a fault was committed, sent punishment. Pharaoh Khety III taught his son that every bad deed led to a similar one: "I did a similar thing so that a similar thing happened" (referring to the looting of the necropolis at Thinis).[23] This religious conception was at the heart of all Egyptian legal cases. In regicide proceedings, the pharaoh's assassination was denied by having him speak from beyond the grave. Amenemhat I addressed his son Senusret I in a teaching tale. As for Ramesses III, in the Judicial Papyrus of Turin, it is he – the deceased – and not his successor Ramesses IV – the living – who constituted a twelve-member court of justice. The deceased never forgot to advise the judges: "As for everything that was done, it was they who did it. May all that they have done fall on their heads! I am protected and exempted for eternity".[24] The conspirators were depicted as the "abominations of the land". In shedding royal blood, they were those who had committed a detestable act, those who had violated a taboo, those who had offended the gods: "The abomination of every god and goddess, totally". Legally debaptized, some criminals were given new names that likened them to Apep, the cosmic serpent hostile to Ra, king of the gods; Medsoure "Ra hates him", Panik "The serpent-demon", Parêkamenef "Ra the blind".[25] According to belief, in the afterlife, the dead could attack each other. Consequently, the deceased king had to be eternally protected from enemies and accusers. Good called good, and his good deeds were emphasized. Amenemhat I praised his generosity: "There was no hunger in my years, and there was no thirst"; in the Papyrus Harris I, Ramesses III listed at length his donations to the temples. In this way, Pharaoh was entirely blameless; he was beyond reproach, and the condemned dead could not reach him. As Pharaoh was the one who gave to the poor and gave social status to the orphan, the conspirators were ungrateful: "He neglected the many good things the king had done for him".[26] Evil calling evil, the royal enemies were erased from memory. In the mastabas, the conspirators of the Old Kingdom were destroyed by having their names erased and their images hammered out.[27] Devoted to this damnatio memoriæ, they no longer existed as snarling, dangerous individuals, socially rejected from the world of the living and magically excluded from that of the dead.[28]

Royal Palace

Crime scenes

Archaeology has revealed the existence of royal residences throughout ancient Egypt, dating back to all historical periods: Memphis (Old Kingdom), Lisht (Middle Kingdom), Thebes, Pi-Ramses (New Kingdom), etc. The best documented ruins are Amenhotep III's palace at Malkata and the residences of Akhenaten and Nefertiti at the new city of Amarna. The best-documented ruins are the palace of Amenhotep III at Malqata and the residences of Akhenaten and Nefertiti in the new city of Amarna. Several types of building can be distinguished according to the activities attributed to them: governmental palaces, ceremonial palaces and residential palaces.[29] The figure of Pharaoh, the king of Egypt, is inextricably linked with his place of residence. The term "Pharaoh", in Egyptian per-âa, means "Great House". Originally, this expression referred only to the palace. However, from the New Kingdom onwards, by metonymy, it was also understood to refer to the person who lived there.[30]

Palace guard

Many people were connected to the royal person: servants, doctors, barbers, craftsmen. It goes without saying that in all eras, armed surveillance was required to ensure the sovereign's protection.[29] This activity was the responsibility of the administration of the setep-sa, a term meaning "to escort / watch over / guard (someone)" and, by extension, "royal palace".[31] Egyptian palatial organization, especially in the earliest periods, is now quite difficult to understand and reconstruct. During the Old Kingdom, in all probability, the pharaoh's surveillance was exercised by the Khentyou-shé or Khentyou-shé-khaset corps, respectively "Those who are in front of the gardens" and "Those who are in front of the gardens and mountains". This armed corps was not limited to guarding the palace. They were also responsible for the security of the funeral complexes and royal estates. The function of these men was to serve the pharaoh. They also produced agricultural resources, took part in royal hunts and transported these resources to the palace. This corps was supported by a hierarchy, enabling competent individuals to rise through the ranks. Some viziers began their careers in this corps, such as Mereruka under Teti or Tjejou under Pepi I.[32]

The guards' loyalty to the pharaoh could prove to be faulty. In the best-documented conspiracies, members of the palace guard were always involved. Teti and Amenemhat I clearly perished in treachery; Pepi I escaped twice. On the side of royal power, mistrust was the order of the day.[27] In the Teaching for Merikare, Pharaoh Kheti III advises his son to command the respect of those around him and to suppress all seditious behavior.[33] The Story of Sinuhe and the Instructions of Amenemhat agree in setting the course of the conspiracy against Amenemhat I in the apartments of the royal palace at Lisht. On the night of 7 Hathor A.D. 30 (around February 13, 1958 B.C.),[34][n 4] conspirators massacred the royal guard and assassinated the pharaoh, who was roused from his sleep by the clash of weapons. Before the king's death, Sinouhé was a Shemsou or "follower", i.e. an armed guard attached to the protection of the palace and a servant of the harem. Overhearing a conversation between two plotters, he realized that this was a political murder and fled into the desert, fearing that he might be mistaken for an accomplice.[35]

Harem

From the earliest times, royal prestige was reflected in the practice of polygamy. In ancient Egypt, the Pharaoh was surrounded by a considerable number of wives.

The institution of the Harem, in Egyptian ipet-nesout "king's apartment" and per khener "house of seclusion", was parallel to and independent of the royal administration. It was home to the royal wife, secondary wives and concubines. The latter were known as khekerut nesut "the king's ornaments" and neferut "the beauties". Also living here were the royal children and their nurses, the widows of deceased pharaohs, and the innumerable cohorts of their attendants and servants. All under the direction of the Great Royal Wife or the Royal Mother.[36]

In times of dynastic crisis, a few women rose to pharaonic office: Nitocris, Sobekneferu, Hatshepsut and Twousret. Many other women in the royal entourage became involved in political affairs. Within the harem, competition between the various wives and concubines was extreme. As far back as the Old Kingdom, textual sources attest to the fact that, at certain times, groups of conspirators gathered around high-ranking women. Under Pepi I, the dignitary Ouni was mandated to secretly judge the harmful actions of a queen within the harem. In King Amenemhat's Instructions to His Son, the sovereign bitterly noted the existence of female involvement in a plot against his person: "Since I had not prepared for it [the attack], I had not considered it, and my mind had not considered the imperiousness of the servants. Had women previously recruited henchmen? Is it from inside the palace that troublemakers are extricated?".[37]

Conspiracies in the 6th dynasty

The murder of Teti

The founder of the 6th Dynasty was Pharaoh Teti, known by his Greek name Othoes. His accession to the throne was problematic, as he was not the son of his predecessor Unas. So it is not known whether or not he was a usurper, or how he came to be king. It is known, however, that his links with the previous dynasty were not interrupted, as he was the son-in-law of Ounas, through his marriage to Princess Iput.[38] Unrest may have erupted upon his accession. His Horus name Sehoteptaoui, "He who pacifies the Two Lands", probably indicates that he must have led military pacification operations. The exact length of his reign is unknown. According to the Ptolemaic historian Manetho of Sebennytos (2nd century BC), Pharaoh Teti reigned for thirty years, then perished through the deception of his bodyguards:[39]

The sixth dynasty consisted of six kings from Memphis.

1. Othoes for thirty years: he was assassinated by his bodyguards.— Manetho, fragment 20.

According to Egyptologist Naguib Kanawati, who carried out the archaeological excavation of Teti's burial complex, some disturbing facts suggest that this pharaoh's life was effectively ended by a conspiracy. After studying the mastabas and tombs of his courtiers, it appears that during his reign, Teti feared for his life. Compared to his predecessors, the number of palace guards was considerably increased. The service was reorganized and better supervised. Proof of the royal mistrust, recruitment was concentrated in the inner circle of a few allied families.[40] In addition, many of the tombs were subjected to a meticulous campaign of depredation (damnatio memoriae). This was undoubtedly orchestrated at the beginning of the reign of Pepi I, Teti's legitimate son. A large number of palace guards and servants were thus condemned to be denied access to eternity. Among them were the guards Semdent, Irénakhti, Méréri, Mérou, Ournou, the judge Iries and the administrator Kaaper. For some, the decoration of the tombs remains unfinished, for others only the name has been erased, and for still others their wall representations have been carefully hammered out – either entirely, or in part (head and/or feet). Among the most senior figures to have been disgraced are the vizier Hesi, the weapons supervisor Meréri and the chief physician Séânkhouiptah.[41]

Userkare the usurper

Teti's direct successor was Pharaoh Userkare. His reign was very short: about one year. Whether Userkare was one of Teti's sons, born of a queen or a concubine, is unclear. His name appeared in the Turin King List and the Abydos King List. This fact, however, does not prevent us from thinking that he was an usurper. Having arrived on the throne by violence, he was undoubtedly ousted a few months later by a faction of legitimists.[42] The viziers Inoumin and Khentika, who served under both Teti and Pepi I, were completely silent on Userkare, and none of their activities during the latter's reign are recorded in their tombs.[43] Moreover, the tomb of Méhi – a guard who served under Teti, Userkare and Pepi – shows an inscription indicating that Teti's name had been erased and replaced by that of another king. This name was subsequently erased and replaced once again by that of Teti.[44] It is possible to imagine that Mehi transferred his allegiance from Teti to Userkare and then, when Pepi came to the throne, turned back. This reversal was unsuccessful, however, as work on the tomb came to an abrupt halt, and Méhi was never buried there.[45]

Conspiracies under Pepi I

According to Egyptologist Naguib Kanawati, two conspiracies took place during the reign of Pepi I. The first undoubtedly took place in the early days of the reign. The biography of the high dignitary Ouni, inscribed in his Abydaean mastaba, mentions that a secret trial was held within the harem to judge the misdeeds of a royal wife. The details, the ins and outs, are unknown. The charge is not mentioned, but the case appears to be highly serious:[46]

His Majesty appointed me Government Officer at Hiéracônpolis, because he trusted me more than any of his servants. I listened to the quarrels being alone with the vizier of the State in every secret affair and every thing that touched the name of the king, the royal harem, the tribunal of the Six (...). There was a trial in the royal harem against the royal wife, a great favorite in secret. His Majesty asked me to judge the case alone, without any State vizier or magistrate except myself, because I was capable, because I was successful in His Majesty's esteem, because His Majesty had confidence in me. It was I who put the minutes in writing, being alone, with a Government Officer in Hieracônpolis who was alone, even though my function was that of director of the employees of the great palace. No one in my position had ever heard a secret of the royal harem before, but His Majesty made me listen to it, (...).

— Biography of Ouni (excerpts). Translation by Alessandro Roccati.[47]

The exact length of Pepi I's reign is unknown. The ancient historian Manetho attributes fifty-three years to[48] him. Modern Egyptologists, however, are divided on the matter, with estimates ranging from thirty-four to fifty years.[49] According to Austrian Egyptologist Hans Gœdicke, the trial took place in the 42nd year of the reign, and it was the mother of Merenre I, the successor, who plotted against the sovereign.[50] Naguib Kanawati does not accept this hypothesis. According to him, archaeological evidence suggests that a number of courtiers were involved in a second affair around the 21st year of the reign. Most were sons of men in whom Pharaoh Teti had placed his trust. In all likelihood, the plot was instigated by the vizier Raour. His tomb is in Teti's necropolis, and he is the son of Shepsipouptah, one of Teti's sons-in-law. The plot failed, and Vizier Raour was severely condemned.[51] As proof, his name and image were hammered into his tomb.[52] The aims of this second plot are not known. The aim was undoubtedly to assassinate Pepi I and replace him with one of his many sons.[53]

Revenge of Queen Nitocris

According to some ancient Greek historians, the 6th Dynasty ended with the tragic reign of Queen Nitocris (Greek for Neitiquerty). This statement should be treated with caution. This lineage reigned around the 21st century, and the facts reported are already almost 2,000 years old at the time of their transmission. The historian Manetho of Sebennytos gives a very fanciful description of this ruler: "A certain Nitokris reigned, the most energetic of men and the most beautiful of women of her time, blonde with rosy cheeks. It is said that the third pyramid was built by the latter, ostensibly showing the aspect of a hill" (Ægyptiaca, fr.20–21).[54] According to the Greek Herodotus, the penultimate pharaoh was assassinated as the result of a plot. If this is true, it probably refers to Pharaoh Merenre II. His sister, Pharaoh Nitocris, avenged his death by drowning the conspirators at a banquet, then committed suicide by throwing herself into the flames of a brazier. There are no Egyptian sources to confirm this historical episode with any certainty. As it stands, it's impossible to say whether this is a true fact or a pseudo-historical anecdote.[55] For the moment, archaeology has yet to uncover any traces of this woman's reign. Nor has it yet confirmed the murder of Merenre II.[56] As for Nitocris, while the acts attributed to her give rise to the greatest skepticism, her historical authenticity is indisputable. Doubts remain, however, as to whether she was male or female. Fragment 43 of the Turin King List attests to the existence of the name Neitiquerty, but it is unclear whether this name should be attributed to the queen in question or to King Netjerkarê.[57]

This woman who reigned in Egypt was called Nitocris, like the queen of Babylon. They told me that the Egyptians, after having killed her brother, who was their king, gave her the crown; that she then sought to avenge his death, and that she killed a large number of Egyptians by artifice. At her behest, a vast apartment was dug out of the ground, ostensibly for feasting purposes, but she really had other plans. She invited to a meal a large number of Egyptians whom she knew to be the main perpetrators of her brother's death, and while they were at table, she let in the waters of the river through a large secret canal. Nothing more is said about this princess, except that after doing this she rushed into an apartment covered in ashes, in order to escape the vengeance of the people.

— Herodotus, Histories – Book 2, 100. Translation by Larcher.[58]

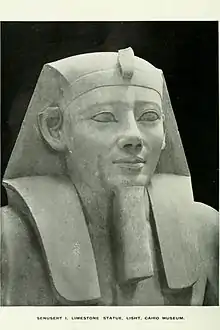

Assassination of Amenemhat I

Tragic night at the palace

The assassination of Amenemhat I in the 30th year of his reign and the stormy conditions under which his eldest son Senusret I succeeded him are documented in two important literary sources: the Story of Sinuhe and the Instructions of Amenemhat to his Son. The old king was about to celebrate his first Sed-festival, intended to regenerate his divine power. Neglectful, he had not yet let the country know which son would succeed him in the event of his death.[59] His natural successor, Prince Sesostris, was absent from the palace, busy waging war in the Libyan desert, no doubt to commit razzias to finance the lavish expenses of the royal jubilee.[60] Against this backdrop, a vast plot was hatched to eliminate the sovereign and his suitor. One night, some of the harem's praetorian guards rose up against their master, entered the royal apartments and assassinated the pharaoh. This tragic evening is recounted in the Teaching of the King, in which the victim is given the floor posthumously:[61]

It was after dinner, after dark. As I had taken a moment to relax, I lay down on my bed, let myself go, and my mind began to follow my somnolence. So the weapons of protection were set in motion against me, and I found myself treated like a desert snake. When I awoke to the fight and regained my senses, I realized that it was a battle involving the bodyguards. As for the fact that I rushed in with weapons in hand, I made the cowards retreat under the blows. But there are no brave men at night, there are no lone fighters. Success cannot come without a protector.

As recounted at the beginning of the Story of Sinouhe, Prince Senusret was informed of the attack by a messenger. No doubt he was also warned that some of his brothers in the ranks of his army were involved in the plot. Without warning anyone, he returned precipitately to the palace, leaving his army behind, fearing that the same fate would befall him. We don't know how Senusret regained control of the situation or how he managed to be crowned. It is, however, attested that the beginning of his reign was one of civil war, and that the new sovereign was forced to brutally suppress seditious forces aligned against him.[63]

Crime suspects

Instructions of Amenemhat to His Son and the Story of Sinuhe clearly suggest that members of the royal family were involved in the conspiracy. In the first work, from the afterlife, Amenemhat I gives his son Senusret I prudent advice. The king is a lonely man with no family, no friends and no devoted servants:

So beware of subjects who don't come forward and for whom no one has worried about the terror they may inspire. Do not approach them when you are alone. Don't trust a brother. Keep away from friends. Don't make friends. There's no point! When you sleep, let your own heart watch over you, for a man has no followers on the day of trouble.

— Instructions of Amenemhat to his son, (excerpt). Translation by Claude Obsomer.[64]

Unless a judicial papyrus is discovered one day – as in the case of the plot against Ramesses III – the identity of the plotters and the name of Sesostris' rival brother will never be known. However, one hypothesis can be put forward. The conditions of Amenemhat's accession to the throne are still rather nebulous, but it is fairly certain that he passed from the role of vizier to that of pharaoh. Founder of a new dynasty, the twelfth, established at Lisht, Amenemhat succeeded Mentuhotep IV, the last representative of an 11th dynasty established at Thebes. In 1956, Georges Posener put forward the hypothesis of a Theban origin for the plot. Senusret's rival brother could have come from the Mentuhotep dynasty through his mother, a secondary wife of Amenemhat. One of the aims of the plot would then have been to bring royal power and administration back to Thebes.[65] Moreover, as Lilian Postel pointed out in 2004, we still don't know who King Qakarê Antef was.[66] His identity is attested only by graffiti in Lower Nubia. His first name – Antef – is borne by several rulers of the 11th Dynasty, and his Horus Name – Sénéfertaouyèf – is very close to the Horus Name – Séankhtaouyèf – of Mentuhotep III, the last great representative of the 11th Dynasty. Under these conditions, and with the usual reservations, it's tempting to link this Qakarê king to the troubles reported in Upper Egypt by certain inscriptions at El-Tod and Elephantine at the beginning of Senusret's reign.[67]

Murder of Amenemhat II?

With regard to the 12th Dynasty, the historian Manetho mentions the regicide of Pharaoh Ammanemês, i.e. Amenemhat. However, on closer inspection, it's not Amenemhat I as mentioned in Egyptian sources, but his grandson Amenemhat II, son of Senusret I:

The 11th dynasty comprised sixteen pharaos from Thebes who reigned for forty-three years. After them, Ammenemês assumed the role during sixteen years (…). The twelfth dynastie comprised seven pharaos from Diospolis

1. Sesonchosis, son of Ammenemês

2. Ammanemês, for thirty-eight years: he was murdered by his own eunuchs.

3. Sesôstris, for forty-eight years (…)— Manetho, Ægyptiaca, fr. 32 and 34.[68]

The interpretation of this statement is difficult. In itself, Manetho's work is lost. All that remains of it are epitomes, i.e. quotations, more or less correct, gleaned from Jewish and Christian authors of the first centuries of our era. Under these conditions, it is hardly possible to prejudge Manetho's true thought. Egyptologists are generally of the opinion that Manetho has got the wrong pharaoh, and was in fact talking about the assassination of Amenemhat I by his own guards. This is not impossible, as the author's assertions are often in flagrant contradiction with archaeological discoveries, particularly concerning the length of reigns. On the other hand, the possibility of a second murder during 12th dynasty cannot be totally ruled out. After all, the murder of Teti-Othoes reported by Manetho seems to be confirmed by archaeology, despite the absence of an Egyptian textual tradition.[69]

In the current state of knowledge, Amenemhat II's reign is poorly documented, and what we know about him is uncertain. His reign was a long one, lasting at least thirty-five years, which is fairly close to the Manethonian figure. However, the royal power seems to have been rather effete and in competition with a few governors well established in the provinces.[70]

The Zannanza affair

The murder of a Hittite prince

With some hesitation, and after inquiring into the seriousness of the request, Suppilliuma decided to accede to the Egyptian request by sending Prince Zannanza. Hittite archives attest that Zannanza never reached his destination. It is likely that an Egyptian faction hostile to this alliance project did not hesitate to assassinate him:

And as moreover, their sovereign Nipkhourouriya[n 5] had died, the queen of Egypt who was the royal wife sent a messenger to my father and wrote the following: My husband is dead. I have no sons. But they say your sons are many. If you give me one of your sons, he will be my husband. I will never take one of my servants as my husband! [...] I'm afraid.

— Geste de Shouppilouliouma.[71]

With some hesitation, and after inquiring into the seriousness of the request, Suppilliuma decided to accede to the Egyptian request by sending Prince Zannanza. Hittite archives attest that Zannanza never reached his destination. It is likely that an Egyptian faction hostile to this alliance project did not hesitate to assassinate him:

When they brought this tablet, they spoke thus: "The men of Egypt have killed Zannanza" and reported this: "Zannanza is dead". And when my father heard the news of Zannanza's murder, he began to lament about Zannanza and, addressing the gods, he spoke thus: "O gods! I have done nothing wrong, yet the men of Egypt have done this against me, and what's more, they have attacked the border of my country!"

— Mourshilli's II prayers against the plague.[72]

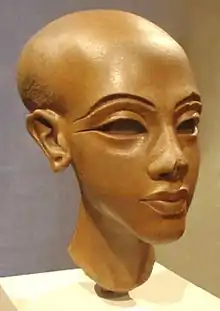

Merytaton's intrigues

Hittite sources refer to Akhenaten's widow as Dakhamunzu "The King's Wife",[73] so her true identity is not revealed. Egyptologists have put forward various suggestions for identifying her: Nefertiti, Kiya, Meritaten or Ankhesenamun.[74] According to Marc Gabolde, a specialist in the 18th Dynasty and the Amarna period, the most consistent identification is Mérytaton. The eldest daughter of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, she rose to the rank of Great Royal Wife after the death of her mother in the sixteenth year of her father's reign.[n 4] A few months later, in the year 17, Akhenaten died in his turn.[75] Clearly, in order to retain power, Meritaten – or rather her supporters, since she was aged between twelve and fifteen – tried to oust the clan supporting Tutankhamun, the legitimate prince aged between four and six.[76] In a difficult military and geopolitical context, Merytaten tried to pull off a double coup by conciliating the Hittites. To this end, she asked Suppilliuma to send her one of his sons to become her husband and a puppet pharaoh. While the Hittite prince Zannanza was on his way to Egypt, priests in Merytaten's entourage drew up an official title for this future king: "Ânkhéperourê Smenkhkarê".[n 6] Assassinated on the way or barely installed in Amarna, the Hittite could not be enthroned. Merytaten then began a solitary reign, under the recycled title of "Ânkhetkhéperourê Nefernéferouaton".[n 7] This female reign was short-lived, lasting around three years. We know nothing of Merytaten's fate, whether she died a natural or induced death. Nor do we know where she was buried. It probably wasn't very sumptuous, or it would have been discovered by now. Very legitimately, the young Tutankhamun succeeded her, strengthened by the support of Ay and Horemheb.[77] It also remains to be seen who ordered the physical elimination of Zannanza-Smenkhkarê. One possible suspect is general Horemheb, who was in control of the Egyptian army at the time.[78]

Twilight of the 18th dynasty

Tutankhamun assassinated?

Tutankhamun is currently one of the world's best-known pharaohs. This fact dates back to 1922, when Howard Carter discovered his burial treasure in the Valley of the Kings. The study of his mummy proved that he did not die of old age, but around the age of sixteen or seventeen, probably in the first months of his tenth year of reign.[79] The cause of this premature death is not explained by Egyptian textual sources. This void has allowed many contemporary authors to construct various hypotheses: assassination, accident or illness. The murder hypothesis was first put forward in 1971 by R. G. Harrisson of University of Liverpool. According to this anatomist, who was authorized to X-ray the mummy in 1968, a fragment of intrusive bone was embedded in one of the skull's resin deposits. This wound behind the left ear suggests that the young sovereign was killed by a violent blow to the back of the head.[80] This proposition attracted the interest of English Egyptologist Carl Nicholas Reeves, author of a 1990 book on Tutankhamun.[81] In 2006, the American police officer Gregory M. Cooper and crime analyst Michael C. King came to suspect the treasurer Maya, queen Ânkhésenamon, the divine father Ay and general Horemheb, the last two having succeeded the victim,[82] in their search for the perpetrator of the crime. However, as early as 2002, a critical study called into question the radiological findings of 1971.[83] In 2005, new medical CT scans definitively invalidated the cranial fracture hypothesis, as no trauma was revealed. It is far more likely that the king, limping and in poor health, succumbed to the fatal consequences of a leg fracture. Combined with an immune deficiency, this accident would have caused severe and fatal septicemia.[84]

Eviction of Prince Nakhtmin

The end of the 18th dynasty was marked by dynastic difficulties and, consequently, by severe struggles for influence. King Tutankhamun ascended the throne at a very young age (around six or seven) and died, before his twenties, without issue. This dynastic void allowed individuals from outside the royal family to be enthroned. Four men marked this period: the vizier Ay and the military men Horemheb, Nakhtmin and Ramesses. The first two held the highest offices of government under Tutankhamun. On the latter's death, Ay became pharaoh and, at least until the beginning of his reign, he and Horemheb maintained the tense but peaceful relations they had enjoyed during the late king's reign. However, their relationship seems to have changed shortly afterwards. Through a number of propaganda actions, such as inscriptions on statues, Horemheb emphasized his governmental abilities and thus tried to discredit Ay in his role as sovereign. Already in his sixties, Ay prepared his succession by naming Nakhtmin (his son or nephew) as crown prince. As a result, Ay relegated Horemheb to a lesser influence and replaced him with Nakhtmin to carry out some of his duties. It is not known exactly when Nakhtmin was promoted, but this must have created strong hostility between Ay and Horemheb. If Horemheb did not overthrow Ay, it was probably because Ay was old and would soon die. In fact, his reign did not exceed four years. In the end, Horemheb became king after the death of Ay, although Nakhtmin was designated as his successor. There is no documentary evidence that Horemheb pushed Nakhtmin out, physically eliminated him or, more peacefully, that Nakhtmin died of illness before the death of Ay.[85] However, if Nakhtmin was still alive, then it's safe to assume that his ouster was the result of a conspiracy. One hypothesis can be cautiously advanced: on the death of Ay, Prince Nakhtmin was preparing to take the throne and was in charge of the deceased's funeral, but Horemheb managed to oust him during the coronation preparations.[86] In any case, some time after taking power, Horemheb began to erase all representations of Ay from monuments, as well as those of his entourage. This damnatio memoriae was also particularly harsh on queen Ânkhésenamun, Tutankhamun's wife.[87] Whether there was a conspiracy or not, Horemheb managed to maintain his position on the throne. His main supporter was his designated successor, the vizier Paramessu, who under the name of Ramesses I inaugurated the prestigious 19th dynasty.[88]

Ramses II, challenged?

Writer and Egyptologist Christian Jacq is a prolific author of historical novels set in the age of the Pharaohs. In 1995–1996, in a pentalogy devoted to Ramesses II, this author popularized the idea of the existence of an elder brother – in this case Shenar – who had been ousted from the throne and was in conflict with Ramesses (thirteen million copies sold in 2004, including 3.5 million in France).[89][90] On this precise point, the question is to know whether the plot of this novel rests on a foundation of truth (however thin) and whether Ramesses the Great saw his authority called into question, at one time or another by someone close to him, before or during his sixty-seven years of reign.

The Méhy case

In 1889, James Henry Breasted noticed at Karnak the added and then hammered representation of an individual in a war scene in which Seti I, father of Ramesses II, was massacring Libyans. According to this archaeologist, it is a representation of an elder brother whom Ramesses had kidnapped after his accession to the throne. As he had no first name, the archaeologist referred to this individual as "X". In Breasted's view, according to a hypothesis put forward in 1905 and reformulated in 1924, Ramesses plotted to supplant this elder brother in order to deprive him of his right to the throne. Ramesses would have implemented this conspiracy as soon as Seti's funeral, and without hesitation.[91] For a time, the name of Nebenkhasetnebet was put forward for this hypothetical older brother. However, there is no convincing evidence to suggest that Seti had two sons.[92]

In 1977, thanks to new excavations, William Murname came to the conclusion that the Karnak fresco represented not a fallen prince, but the soldier Mehy, a commoner whose family origins are unknown. This important figure was also known for his organizational skills, especially during major troop movements abroad. There seems to be no doubt about his proximity to Seti I – far more, in any case, than his honorary titles would suggest. To date, however, it has not been established that Mehy was ever elevated to the rank of royal heir, a position successively occupied by the commoners Ay, Horemheb and Ramesses I before their enthronement. As Seti's right-hand man and a man of influence, Mehy was undoubtedly despised and even feared by the young Ramesses – perhaps even by King Seti in his final years.[93] It is therefore possible to imagine that Ramesses saw Mehy as a possible rival to the throne. Indeed, throughout his reign, Ramesses II never ceased to proclaim his right to the throne, no doubt to dissuade a member of the powerful military caste, Mehy or otherwise, from taking his place.[94]

Treaty of extradition

Despite its length (sixty-seven years), the reign of Ramesses II was not rich in major warlike events. During the first decade, five campaigns were recorded in Syria-Palestine, including the famous battle of Kadesh (year 5) and the siege of Dapur (year 8).[n 4] A raid was recorded in Libya in year 6/7, and a revolt was put down in Nubia in year 19/20. The cessation of hostilities against the Hittites (Khatti country) probably coincided with the death of Emperor Muwatalli II. He was succeeded by his eldest son, Mursili III. After a few years, he was ousted by Hattusili III, his uncle. Hattusili III's reign was marked by his determination to gain full legitimacy in the eyes of the other kings. He achieved this by concluding a peace treaty with Ramses II in the year 21. This desire for appeasement manifested itself in two diplomatic marriages, with the Egyptian king marrying two Hittite princesses in 34 and 40 AD.[95]

The peace treaty concluded between Ramesses and Hattushili placed great emphasis on the extradition of rebels and conspirators. It also provided information on the legal penalties for treachery (death, amputations). The treaty was aimed at both Ramesses' and Hattushili's opponents. However, as the treaty seems to be a Hittite initiative, the first aim was to bring Hittite opponents back home. For example, we know that emperor Mursili, deposed by Hattushili, sought refuge with Ramesses (year 18), and that this flight led to a diplomatic crisis:[96]

If an important man flees the land of Egypt and arrives in the land of the great master of the Khatti, or in a city or region belonging to the possessions of Ramesses-loved-of-Amon, the great master of the Khatti must not receive him. He must do what is necessary to deliver him to Ousermaâtrê Sétepenrê, the great king of Egypt, his master.

If one or two unimportant men flee and take refuge in the land of Khatti to serve another master, they must not be allowed to remain in the land of Khatti; they must be brought back to Ramesses-beloved-of-Amon, the great king of Egypt.

If an Egyptian, or even two or three, flee from Egypt and arrive in the land of the great master of Khatti, (...) in this case, the great master of Khatti will apprehend him and hand him over to Ramesses, the great ruler of Egypt: he will not be blamed for his mistake, his house will not be destroyed, his wives and children will live, and he will not be put to death. No injury will be inflicted on him, neither to the eyes, nor to the ears, nor to the mouth, nor to the legs. No crime will be imputed to him (follows the reciprocity clause on the Hittite side, using exactly the same terms).

— Treaty of Hittito-Egyptian (excerpt). Translation by Christiane Desroches Noblecourt.[97]

Era of conspiracies

End of the 19th dynasty

Between the death of Merneptah, son of Ramesses II, and the end of the 19th dynasty, there was a troubled period of some fifteen years. During this short era, three pharaohs – Seti II, Amenmes and Siptah – and one queen – Twosret – succeeded one another before Sethnakht, the founder of the 20th dynasty, seized power. For Ramesses III, between Merenptah and his father Sethnakht, only Seti II was legitimate. The question is why Amenmes, Siptah and Taousert were rejected as illegitimate. Because of the paucity and contradiction of documentation, this period poses a number of problems for Egyptologists, especially as regards the genealogical links between the above-mentioned figures. What's more, most of the intrigue took place in the capital Pi-Ramesses, of which there are hardly any remains and therefore no archives. It is relatively certain that all the political players of the time were Ramessides. During his sixty-seven-year reign, Ramesses II sired a large number of descendants. He is known to have had at least fifty sons and fifty-three daughters.[98] Consequently, the number of his grandchildren is considerable and largely undetermined, due to gaps in the documentation now available. All of them held important positions in the country's civil, military and religious administrations. After the death of Merenptah, pre-existing tensions boiled over and several serious conflicts arose within this vast royal family. Powerful clans were pitted against each other, and intrigues were woven around the main representatives of the lineage of Merenptah, the last pharaoh to reign undisputed.[99]

Amenmes revolt against Seti II

When Merenptah died, his son Seti II succeeded him. Born to Queen Isetnofret, he ascended the throne at the age of twenty-five.[100] The first months of his reign appear to have been peaceful. However, this apparent calm concealed probable family dissensions. His new power was very fragile, and he seemed to have to deal with his wife Twosret's clan. The most likely hypothesis is that this Great Royal Wife was a granddaughter of Ramesses II through her mother or father. The power of this woman – and the relative weakness of her husband – is demonstrated by the location of her tomb (KV14) in the Valley of the Kings, a few steps from that of Seti (KV15), and not in the Valley of the Queens as usual.[101] This surprising location is still largely unexplained. It is disturbing to note that at the very moment when Seti granted this privilege to his wife (end of year 2), the usurper Amenmesse appeared on the scene, as if the rise in power of the queen and her clan had shattered a fragile family equilibrium.[102] Pharaoh Amenmesse's origins lie in the Ramesside family. His mother was probably Queen Takhat, one of Merenptah's wives and daughter of Ramesses II. Consequently, the conflict between Seti II and Amenmesse appears to have been a struggle between two half-brothers.[103] Amenmesse possessed a certain legitimacy, and a number of power networks rallied around him in the south of the country, in Nubia and Thebaid. In particular, he secured the support of Româ-Roÿ, the powerful high priest of Amun.[104] Amenmesse certainly tried to move further north, but his progress was halted in the Abydos region, which remained loyal to Seti.[105] For a few years, Amenmesse's power continued in the south of the country, but in the end, Seti succeeded in gaining the upper hand. The end of Amenmesse remains a mystery. He was probably brutally eliminated by his rival, and his body was never laid to rest in the tomb (KV10) provided for the purpose. Destined for oblivion, no funerary cult is attested by archaeology.[106] Under the damnatio memoriae, his name was erased from all monuments. In addition, a vast purge was carried out in the administration of the Thebaid, with all Amenmesse's supporters also removed from power.[107]

Bay, the "kingmaker"

The weakening of Seti II's power is reflected in the rise of the ambitious Chancellor Bay. Of Syrian origin, his career was meteoric. He was royal scribe and cupbearer at the beginning of the reign, and grand chancellor at the end.[108] Pharaoh Seti died in the sixth year of his reign without a designated successor, his son Prince Seti Merenptah having predeceased him. This dynastic void gave rise to new rivalries within the Ramesside family. Two clans competed for power. The first was organized around Queen Twosret, the king's widow, and the second around Bay, the most powerful of the courtiers. For a time, it's the latter who had the upper hand. In all likelihood, young Siptah ascended the throne thanks to Bay's support. The chancellor boasted that he had "established the king on his father's throne".[109] Later considered illegitimate, Siptah was clearly not descended from Seti. His mother was a certain Soutérery, also of Syrian origin. His father's name is not known with certainty, but he was probably the usurper Amenmesse, Seti II's half-brother. To exercise his power, Bay placed a malleable individual on the throne. Siptah was very young (twelve-fifteen) and infirm. Afflicted with atrophy of the foot, linked to a genetic malformation or poliomyelitis, the new pharaoh could only move with great difficulty.[110] To consolidate his power, Chancellor Bay established a duality of power: he was in charge of the actual administration of the country, while Siptah was responsible for the ritual dimension of the pharaonic function. Bay's ambition knew no bounds, and he arrogated to himself the right to be buried in the Valley of the Kings (KV13) in a tomb opposite that of Siptah (KV47).[111] At first, Queen Twosret was obliged to form an objective alliance with Bay to allow current affairs to take their course. However, in the year 5 of Siptah, the conflict between the queen and the chancellor escalated, to the greater benefit of the first. Labeled a "great enemy", i.e. a rebel and a schemer, Bay was killed without it being known whether he had been executed after a proper trial or assassinated in a plot hatched by the queen and her supporters.[112][113]

Sethnakht versus Twosret

After the physical elimination of Chancellor Bay, Queen Twosret used every means at her disposal to impose her authority, even though the young Siptah remained Pharaoh. The meagre documentation available gives the impression that she wanted to institute a power similar to that of Pharaoh Hatshepsut during the minority of Thutmose III.[114] However, Siptah disappeared shortly afterwards, in the sixth year of his reign, aged between twenty and twenty-five. The reasons for his death are unknown, but as soon as he disappeared, Queen Twosret acted as if he had never existed, counting down the years of her own reign not from Siptah's death, but from the death of her husband Seti II.[115] The end of Twosret's reign is poorly documented. The earliest known date is year 8, less than two years of effective solitary reign. His successors Setnakhte and Ramesses III did not consider him legitimate.[116] In all likelihood, a civil war broke out in the north of the country and the instigator of the conflict seems to have been Sethnakht, the founder of the 20th dynasty. A member of the military caste, Sethnakht clearly resented the arrival of a woman at the head of the country. He therefore began his reign not from the day of his victory, but from the moment he decided to take up arms against the pharaoh.[117] Sethnakht's genealogy is unknown. There are no documents linking him to the line of Ramesses II, but royal grandsons are not in the habit of emphasizing their origins. It's hard to believe, however, that all the grandsons and great-grandsons of Ramesses II who were still alive at the time could have accepted without protest the accession to supreme power of a brand-new royal family – parvenus, in short.[118] The most likely hypothesis is that the pharaoh Twosret had lost the reins of power after coming into conflict with the clan descended from prince Khaemweset, the vizier Hori having lent his support to Sethnakht.[119] Nothing is known of Twosret's death. Clearly, despite the conflict, Sethnakht presided over his funeral with the political aim of legitimizing his reign.[120] Aging, Sethnakht died after two years of reign, leaving his place to his son Ramesses III, already in his forties.[121]

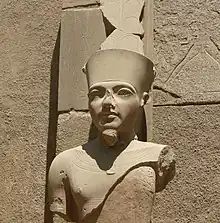

Conspiracy against Ramesses III

The facts

In the 32nd year of Ramesses III's reign, the Harem Conspiracy took place, a coup d'état aimed at replacing the legitimate heir, the future Ramesses IV, son of Queen Iset, with Prince Pentawer, son of Queen Tiye, a secondary wife. This affair is documented by a series of writings, including the Judicial Papyrus of Turin and the Papyrus Harris. According to a medical imaging examination carried out on the mummy in 2012, Ramesses III appears to have had his throat slit.[122][123] On this point, the written sources deny the success of the action behind stereotyped formulas; no doubt there was some reluctance to express the facts clearly.[124] The conspiracy was on a grand scale, involving many of the harem's dignitaries. Armed men were called in to march against the palace. The plot's ramifications extended to the provinces, where seditious men were called in to act as troublemakers. However, the conspirators led by Queen Tiye failed to replace the legitimate heir. Gaining the upper hand, Ramesses IV set up a court of justice made up of twelve magistrates. Sentences rained down on some thirty plotters, both active and passive: twenty-two were executed, 11 were incited to suicide, including Prince Pentawer.[125] As a sign of the decay of monarchical power, three judges and two policemen were bribed during the trial with promises of parties within the harem. Denounced, they were arrested for collusion and sentenced to have their noses and ears removed.[126] The conspiracy also had a supernatural dimension, as the conspirators had enlisted the help of priests who were experts in witchcraft. Throughout his reign, Pharaoh was protected by a prophylactic magic based on the identification of the king with Ra and the seditionists with Apep. To achieve their ends, the plotters used bewitchment to neutralize the palace guard and dismantle the magical pomp surrounding the pharaoh.[127]

Ramesses III's throat slit

Of all the pharaohs suspected of having perished in a conspiracy, only the mummy of Ramesses III has survived. Like some 50 other royal and princely mummies, Ramesses' remains were discovered on July 6, 1881, by Gaston Maspero in the royal hideout of Deir el-Bahari (TT320). Five years later, on June 1, 1886, the mummy was stripped of its bandages by the same Egyptologist.[128] Now on display at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, the body is wrapped in a brownish-orange cloth secured with ordinary cloth strips. The face is masked by a compact layer of embalming resin, but it appears that the sovereign's head and face have been closely shaved. The eyelids have been removed and the two orbital cavities emptied and filled with rags. The arms are crossed over the chest, both hands placed flat on the shoulders. The body appears vigorous and age at death is estimated at sixty-five.[129][130] The mummy was X-rayed in the 1960s, but the images failed to reveal the cause of death. In 1993, in a biography devoted to Ramesses III, Pierre Grandet denied that the conspiracy had caused the king's death: "it seems more satisfactory to suppose that the conspiracy did not have death as its goal but as its pretext".[131]

According to a 2012 study by a group of scientists led by Zahi Hawass, the king appears to have died a violent death.[132] CT images revealed a severe wound in the throat of Ramesses III's mummy, directly below the larynx. The wound is around 70 mm wide and extends deep into the bone, between the 5th and 7th cervical vertebrae. In the soft tissue, all the organs in this region have been severed, including the trachea, esophagus and large blood vessels. The extent of the wound indicates that it could have caused almost immediate death. A small, flat Oudjat or "Eye of Horus" amulet, made of semi-precious stone and about 15 mm in diameter, was inserted by the embalmers into the lower right edge of the wound to guarantee the deceased protection and good health.[133]

Main conspirators

The conspiracy was clearly a matter of succession. Pharaoh Ramesses III intended to make his son, Prince Ramesses, his successor. At the time of the plot, this son of Queen Iset Ta-Hemdjert held the titles of Crown Prince, General and Royal Scribe. The conspirators' aim was to override the old monarch's will and place Prince Pentawer, son of Queen Tiye, at the head of the country. Everything was ready for his reign to begin; a titulary had even been drawn up:

Pentawer, the one given this other name. He was brought before the court because he had been in league with Tiye, his mother, when she was plotting with the women of the harem, rebelling against her master. He was brought before the cupbearers for questioning. They found him guilty. He was left in his place. He killed himself.

— "Judicial Papyrus of Turin" (excerpt). Translation by Pascal Vernus.[134]

According to the court record, more than Pentawer, Queen Tiye was the main instigator of the plot. Thanks to her influence in the harem, she was able to rally other women in this institution. The list of convicts indicates that at least six women were involved, all of them porters' wives.[134] High-ranking harem officials, who were supposed to ensure security, were also involved: Panik, director of the king's chamber, and his immediate subordinate Pendouaou, scribe to the king's chamber. On the passive side, the controllers Patchaouemdiimen, Karpous, Khâmopet, Khâemmal and the cupbearer Sethyemperdjehouty, the scribe Pairy and the harem lieutenant Imenkhâou were convicted of non-indictment.[135]

The chamberlain Pabekkamen is probably the most important figure in the conspiracy, his role being to transmit orders outside the palace in order to organize armed sedition:

He was put on trial because he had joined forces with Tiye and the women of the harem. He began to take their messages outside to their mothers and brothers who were there, namely, "Gather people, wage war to rebel against your master!"

— "Judicial Papyrus of Turin" (excerpt). Translation by Pascal Vernus.[136]

List of conspirators

Most of the names of the conspirators against Ramesses III have been erased from the monuments where they were engraved. In the trial documents, such as the Judicial Papyrus of Turin, they are changed into names of infamy which, while retaining their consonance, invert their meaning, thus pronouncing a veritable curse.[137]

The list below is taken from the Papyrus judiciaire:

| Infamous name[n 8] | Meaning | Real name | Meaning | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pebekkamen | The blind servant | Never revealed | Amun's servant | Chef de la chambre.[n 9] |

| Mesedsourê | Ra hates him | Meryrê | Ra's beloved | Cupbearer |

| Panik | The devil | Harem master | ||

| Pendouaou | Scribe to the harem master | |||

| Karpous | Harem controller | |||

| Khâemopet | Harem controller | |||

| Khâemmal | Harem controller | |||

| Sethyemperdjehouty | Seth is in the Temple of Thoth | Harem controller | ||

| Sethyemperamon | Seth is in Amun's temple | Cupbearer | ||

| Oulen | Cupbearer | |||

| Âshahebsed | Pebekkamen assistant | |||

| Palik | Cupbearer and scribe | |||

| Libou Yenen | Cupbearer | |||

| Six women | Wives of men at the harem gate | |||

| Payiri, son of Roumâ | Head of treasury | |||

| Binemouaset | Evil in Thebes | Khâemouaset | Leader of the Kush troops | |

| Payis | The bald | Pahemnétjer | The priest | General |

| Messouy | Scribe in the House of life | |||

| Parâkamenef | Blind Ra | Parâherounemef | Ra is on his right | Chief ritualist priest |

| Iyry | Ritualistic priest, chief priest of the goddess Sekhmet of Bubastis | |||

| Nebdjéfaou | Cupbearer | |||

| Shâdmesdjer | He whose ear is cut off | Ousekhnemtet | He whose walk is easy | Scribe in the House of life |

| Pentawer | Son of Ramesses III and Tiye | |||

| Tiye | Ramesses III's wife | |||

| Hentouenimen | Cupbearer | |||

| Amonkhâou | Harem substitute | |||

| Pairy | Scribe to the King's chamber |

Witchcraft

During the investigation of the case, it became apparent to the judges that the conspirators, in order to achieve their ends, had found it useful to call on a group of priests skilled in the art of sorcery.

The Judicial Papyrus of Turin mentions the names of Parêkamenef, magician, Messoui and Shâdmesdjer, scribes of the house of life, as well as Iyry, director of the pure priests of Sekhmet. The house of life was a kind of library where grimoires were stored, while the cult of the lion goddess Sekhmet required knowledge of incantatory practices. Magical recipes were smuggled out of the royal library, soporific potions were concocted and wax figurines were fashioned to bewitch the palace guards:

He began to make magical writings to disorganize and throw into confusion, making some wax gods and some philtres to render human limbs powerless, and handing them over to Pebekkamen(...) and the other great enemies with these words, "Bring them in," and, sure enough, they brought them in. And when he brought them in, the evil deeds he did were done.

— Papyrus Rollin (excerpt). Translation by Pascal Vernus.[138]

Sentences

According to the judicial papyrus of Turin, Ramesses III – or more precisely Ramesses IV, who used his late father's legal guarantee – set up a twelve-person commission to judge the conspirators. It was made up of two treasury chiefs, Montouemtaouy and Payefraouy, a senior courtier, the flabellum bearer Kar, five cupbearers, Paybaset, Qédenden, Baâlmaher, Pairousounou and Djéhoutyrekhnéfer, the royal herald Penrennout, two scribes from the dispatch office, Mây and Parâemheb, and the army standard-bearer Hori. Three of them allowed themselves to be bribed during the investigation by General Payis, and were in turn prosecuted. Paybaset was replaced by the cupbearer Méroutousyimen; the replacements for Mây and Hori are unknown.[139]

The accused, all described as "great enemies", were referred to the "investigation office" and questioned. They quickly confessed.[140]

The judges drew up several lists of defendants. Those on the first list had their names changed, so that they were doomed to eternal decay. They were executed, but no one knew exactly how. The text simply uses the phrase "Their punishment has come to them". Those in the second category, because of their proximity to the royal office, Pentawer first among them, were condemned to suicide: "They were left to their own devices in the interrogation room. They took their own lives before any violence was done to them". Corrupt judges had their ears and noses mutilated. One of them, Paybaset, committed suicide following this infamous punishment.[141][142]

As for Queen Tiye and those close to the royal family, the ladies of the harem who were accomplices, available sources give no details of their fate.[143]

Notes

- ↑ This myth was recorded during the Ramesside period on a papyrus found at Deir el-Medineh. It is advised to consult the articles: Horus and Set.

- ↑ Hatshepsut's presence compensated for the physical weakness of her husband Thutmose II and the youth of Thutmose III; Neferneferuaten compensated for the young age of the weak Tutankhamun and Tausert for that of Siptah.

- ↑ The theft of the Osirian relics by Set and their recovery by Anubis-Horus is one of the main themes of the Jumilhac Papyrus (Greco-Roman period). For a translation, see Jacques Vandier, Le Papyrus Jumilhac (in French), Paris, CNRS, 1961.

- 1 2 3 The years were counted from each new coronation. As soon as a pharaoh was enthroned, the count started again at year 1.

- ↑ Hittite transcription of the Egyptian name Néferkhéperourê the Name of Nesout-bity of king Akhenaton (Gabolde 2015, p. 70).

- ↑ These two names mean "The becomings of Ra are alive, He whom the Ka of Ra makes efficient", respectively the name of Nesout-bity and the name of Sa-Ra; two of the five components of the titulature.

- ↑ These two names mean "Ra's becomings are alive, Aten's perfection is perfect" (Dessoudeix 2008, pp. 310–311).

- ↑ Name inscribed in the judicial papyrus of Turin

- ↑ i.e. head of the king's "valets de chambre"

References

- ↑ Dictionnaire Le Robert illustré (in French), 1997, pp. 320, 308 et 317.

- ↑ Collectif 2004, Pascal Vernus, « Une conspiration contre Ramesses III », p. 14.

- ↑ Bonnamy & Sadek 2010, pp. 129, p. 533–534 and p. 547–548.

- ↑ Vernus 2001, pp. 160–161.

- ↑ Obsomer 2005, p. 45.

- ↑ Collectif 2004, pp. 12–13, Pascal Vernus, « Une conspiration contre Ramesses III »

- ↑ Herodotus, Book 2, §.

- ↑ Manetho, pp. 53–57.

- ↑ Manetho, p. 67.

- ↑ Collectif 2004, pp. 5–9, « Assassiner le pharaon ! »

- ↑ Collectif 2004, pp. 3–5, Marc Gabolde, « Assassiner le pharaon ! »

- ↑ Adler 1982, Adler 2000

- ↑ Plutarch (trans. Mario Meunier), Isis et Osiris, Guy Trédaniel éditeur, 2001, p. 57–58.

- ↑ Broze, Michèle (1996). Mythe et roman en Égypte ancienne. Les aventures d'Horus et Seth dans le Papyrus Chester Beatty

(in French). Louvain: Peeters. - ↑ Menu 2008, pp. 107–119.

- ↑ Jean Leclant (directeur), Dictionnaire de l'Antiquité (in French), Paris, PUF, 2005 (réimpr. 2011), ISBN 9782130589853, p. 1878–1879 : Reine (Égypte).

- ↑ Gabolde 2015, pp. 120–121.

- ↑ Jan Assmann, Mort et au-delà dans l'Égypte ancienne (in French), Monaco, Le Rocher, 2003, ISBN 2-268-04358-4, p. 80–95.

- ↑ Gabolde 2015, pp. 396–401 and passim.

- ↑ Obsomer 2005.

- ↑ Collectif 2004, Pascal Vernus, « Une conspiration contre Ramsès III », p. 11–12.

- ↑ Sylvie Cauville, Dendara : Les chapelles osiriennes, Le Caire, IFAO, coll. « Bibliothèque d'étude », 1997 ISBN 2-7247-0203-4. Vol.1 : Transcription et traduction (BiEtud 117), vol. 2 : Commentaire (BiEtud 118).

- ↑ Vernus 2001, p. 145.

- ↑ Koenig 2001, pp. 296–297.

- ↑ Koenig 2001, pp. 300–301.

- ↑ Vernus 1993, p. 155.

- 1 2 Kanawati 2003.

- ↑ Assmann 2003, pp. 94–95.

- 1 2 Husson & Valbelle 1992, pp. 22–24.

- ↑ Adolf Erman, Hermann Ranke, La civilisation égyptienne, Tubingen, 1948 (French translation by Payot, 1952, p. 79).

- ↑ Bonnamy & Sadek 2010, p. 604

- ↑ Kanawati 2003, pp. 14–21.

- ↑ Vernus 2001, p. 138 and following.

- ↑ Obsomer 2005, p. 53, note 3

- ↑ Obsomer 2005, pp. 47 and 52–53

- ↑ Christiane Desroches Noblecourt (2000). La femme au temps des pharaons (in French). Paris: Stock/Pernoud. ISBN 978-2-234-05281-9. OCLC 46462982. auto-translated by Module:CS1 translator -->.

- ↑ Vernus 2001, p. 167.

- ↑ Kanawati 2003, p. 148.

- ↑ Aufrère 2010, pp. 95–100.

- ↑ Kanawati 2003, pp. 14–24.

- ↑ Kanawati 2003, pp. 166–167.

- ↑ Kanawati 2003, pp. 169–171.

- ↑ Kanawati 2003, p. 89.

- ↑ Kanawati 2003, pp. 94–95.

- ↑ Kanawati 2003, p. 163.

- ↑ Kanawati 2003, pp. 170–172.

- ↑ Roccati 1982, pp. 187–197

- ↑ Manetho, p. 53.

- ↑ Dessoudeix 2008, p. 97.

- ↑ Aufrère 2010, pp. 100–102.

- ↑ Kanawati 2003, pp. 177–182.

- ↑ Kanawati 2003, pp. 115–116.

- ↑ Kanawati 2003, p. 185.

- ↑ Aufrère 2010, pp. 103–106.

- ↑ Aufrère 2010, pp. 95–106.

- ↑ Clayton 1995, p. 67.

- ↑ Aufrère 2010, pp. 104–105.

- ↑ Herodotus, Book II. §..

- ↑ Favry 2009, pp. 36–37.

- ↑ Menu 2008, p. 118

- ↑ Favry 2009, pp. 31–34.

- ↑ Vernus 2001, pp. 166–167.

- ↑ Favry 2009, pp. 35–42.

- ↑ Obsomer 2005, p. 35.

- ↑ Obsomer 2005, pp. 55–56, notes 22 and 23.

- ↑ Lilian Postel, Protocole des souverains égyptiens et dogme monarchique au début du Moyen Empire (in French), Bruxelles, 2004.

- ↑ Obsomer 2005, pp. 60–61.

- ↑ Manetho, pp. 65–67.

- ↑ Collectif 2004, Sydney Hervé Aufrère, « De la mort violente des pharaons », p. 24.

- ↑ Claude Vandersleyen, L'Égypte et la vallée du Nil (in French), tome 2, pp. 77–82.

- ↑ Gabolde 2015, p. 65

- ↑ Gabolde 2015, p. 66

- ↑ Gabolde 2015, p. 549, note 33.

- ↑ Dessoudeix 2008, p. 310.

- ↑ Gabolde 2015, p. 80.

- ↑ Gabolde 2015, p. 120.

- ↑ Gabolde 2015, pp. 111–113.

- ↑ Aufrère 2010, pp. 117–119. However, according to this author, the queen was not Merytaton but his sister Ânkhésenamon, widow of Tutankhamun..

- ↑ Gabolde 2015, p. 355 et p. 360.

- ↑ Harrisson, R. G. (1971). Postmortem on two Pharaohs – was Tutankhamen's skull fractured ?. Vol. Buried History 4. pp. 114–129.

- ↑ Reeves, Carl Nicholas (1990). The Complete Tutankhamun: The King, the Tomb, the Royal Treasure. Thames & Hudson. p. 128.. Translated from English: Toutânkhamon. Vie, mort et découverte d'un pharaon, Éditions Errance, 2003.

- ↑ King & Cooper 2006

- ↑ Boyer, Richard S.; Rodin, Ernst A.; Grey, Todd C.; Connolly, R. C (2002). "The Skull and Cervical Spine Radiographs of Tutankhamen: A Critical Appraisal". American Society of Neuroradiology. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- ↑ Gabolde 2015, pp. 358–359.

- ↑ Kawai 2010, pp. 286–289.

- ↑ Gabolde 2015, pp. 478–481.

- ↑ Kawai 2010, p. 289.

- ↑ Somaglino, Claire, « Du Delta oriental à la tête de l'Égypte. La trajectoire de Paramessou sous Horemheb » (in French), Égypte, Afrique et Orient 76, 2014, pp. 39–50.

- ↑ L'Expansion / L'Express (2004). "Le club des très gros chèques de l'édition". lexpansion.lexpress.fr (in French). Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ↑ Jacq, Christian, Ramsès (in French), tomes I to V, Robert Laffont, 1995–1996.

- ↑ Breasted, James Henry, A History of Egypt, New York, 1909 (second edition), p. 418.

- ↑ Masquelier-Loorius, Julie, Seti I et le début de la XIXe dynastie (in French), Paris, Pygmalion, 2013, p. 38.

- ↑ Obsomer 2012, pp. 55–59.

- ↑ Feinman, Peter (1998). Ramses and rebellion: showdown of false and true Horus (PDF). pp. 3–4 and notes 21–24..

- ↑ Dessoudeix 2008, p. 339.

- ↑ Obsomer 2012, pp. 194–203.

- ↑ Christiane Desroches Noblecourt, Ramesses, la vraie histoire, Paris, Pygmalion, 1996, pp. 290.

- ↑ Obsomer 2012, pp. 250–280.

- ↑ Servajean 2014, pp. 52–54.

- ↑ Servajean 2014, p. 55.

- ↑ Servajean 2014, pp. 60–61.

- ↑ Servajean 2014, p. 62.

- ↑ Servajean 2014, p. 64.

- ↑ Servajean 2014, pp. 75–76.

- ↑ Servajean 2014, p. 67.

- ↑ Servajean 2014, pp. 80–81.

- ↑ Servajean 2014, pp. 86–88.

- ↑ Servajean 2014, p. 82 and 95.

- ↑ Servajean 2014, p. 96.

- ↑ Servajean 2014, pp. 94–95.

- ↑ Servajean 2014, p. 105.

- ↑ According to a small ostracon discovered at Deir el-Medina (Servajean 2014, p. 115)

- ↑ Grandet, Pierre (2000). "L'exécution du chancelier Bay". BIFAO 100: 339–345..

- ↑ Servajean 2014, p. 118.

- ↑ Servajean 2014, p. 124.

- ↑ Servajean 2014, p. 130.

- ↑ Servajean 2014, p. 138.

- ↑ Servajean 2014, pp. 139–140.

- ↑ Servajean 2014, pp. 138–139.

- ↑ Servajean 2014, pp. 140–144.

- ↑ Grandet 1993, pp. 43–48.

- ↑ Discovery Science France (2014). "La momie de Ramsès III : Ramsès III, le roi assassiné". You tube (in French). Retrieved March 1, 2015.

- ↑ Collectif 2012.

- ↑ Vernus 1993, pp. 153–155.

- ↑ Loktionov 2015, p. 104.

- ↑ Aufrère 2010, pp. 125–128.

- ↑ Vernus 1993, pp. 150–153, Aufrère 2010, p. 129.

- ↑ Grandet 1993, pp. 344–345.

- ↑ Smith 1912, pp. 85–86.

- ↑ Hawass, Zahi; Janot, Francis, Momies : Rituels d'immortalité dans l'Égypte ancienne (in French), 2008, pp. –126–127.

- ↑ Grandet 1993, pp. 336–337.

- ↑ "Le mystère du roi momie" (in French).

- ↑ Collectif 2012, p. 2/9.

- 1 2 Vernus 1993, p. 148.

- ↑ Collectif 2004, p. 15.

- ↑ Vernus 1993, p. 144.

- ↑ Vernus 1993, pp. 144–149.

- ↑ Vernus 1993, pp. 147, 151.

- ↑ Grandet 1993, p. 337.

- ↑ Grandet 1993, p. 338.

- ↑ Grandet 1993, pp. 337–338.

- ↑ Grandet 1993, pp. 156–157.

- ↑ Grandet 1993, p. 340.

Bibliography

- Adler, Alfred (1982). La Mort est le masque du roi: la royauté sacrée des Moundang du Tchad (in French). Paris: Payot. ISBN 2-228-13060-5.

- Adler, Alfred (2000). Le pouvoir et l'interdit: Royauté et religion en Afrique noire (in French). Paris: Albin Michel. ISBN 2-226-11664-8.

- Assmann, Jan (2003). Mort et au-delà dans l'Égypte ancienne. Champollion (in French). Translated by Nathalie Baum. Monaco: Éditions du Rocher. ISBN 2-268-04358-4.

- Aufrère, Sydney H. (2010). Pharaon foudroyé: Du mythe à l'histoire (in French). Gérardmer: Pages du Monde. ISBN 978-2-915867-31-2.

- Bonnamy, Yvonne; Sadek, Ashraf (2010). Dictionnaire des hiéroglyphes : hiéroglyphes-français (in French). Arles: Actes Sud. ISBN 978-2-7427-8922-1.

- Clayton, Peter A. (1995). Chronique des Pharaons: L'histoire règne par règne des souverains et des dynasties de l'Égypte ancienne (in French). Translated by Florence Maruéjol. Paris: Casterman. ISBN 2-203-23304-4.

- Collectif (2004). "Crimes et châtiments dans l'ancienne Égypte". Égypte, Afrique et Orient. Centre vauclusien d'égyptologie. 35.