Computational epigenetics[1] uses statistical methods and mathematical modelling in epigenetic research. Due to the recent explosion of epigenome datasets, computational methods play an increasing role in all areas of epigenetic research.

Definition

Research in computational epigenetics comprises the development and application of bioinformatics methods for solving epigenetic questions, as well as computational data analysis and theoretical modeling in the context of epigenetics. This includes modelling of the effects of histone and DNA CpG island methylation.

Current research areas

Epigenetic data processing and analysis

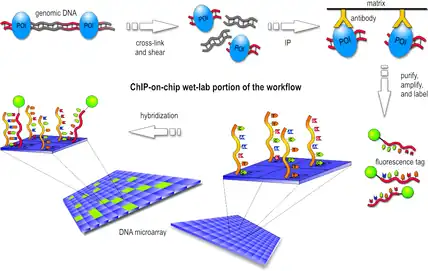

Various experimental techniques have been developed for genome-wide mapping of epigenetic information,[2] the most widely used being ChIP-on-chip, ChIP-seq and bisulfite sequencing. All of these methods generate large amounts of data and require efficient ways of data processing and quality control by bioinformatic methods.

Epigenome prediction

A substantial amount of bioinformatic research has been devoted to the prediction of epigenetic information from characteristics of the genome sequence. Such predictions serve a dual purpose. First, accurate epigenome predictions can substitute for experimental data, to some degree, which is particularly relevant for newly discovered epigenetic mechanisms and for species other than human and mouse. Second, prediction algorithms build statistical models of epigenetic information from training data and can therefore act as a first step toward quantitative modeling of an epigenetic mechanism. Successful computational prediction of DNA and lysine methylation and acetylation has been achieved by combinations of various features.[3] [4]

Applications in cancer epigenetics

The important role of epigenetic defects for cancer opens up new opportunities for improved diagnosis and therapy. These active areas of research give rise to two questions that are particularly amenable to bioinformatic analysis. First, given a list of genomic regions exhibiting epigenetic differences between tumor cells and controls (or between different disease subtypes), can we detect common patterns or find evidence of a functional relationship of these regions to cancer? Second, can we use bioinformatic methods in order to improve diagnosis and therapy by detecting and classifying important disease subtypes?

Emerging topics

The first wave of research in the field of computational epigenetics was driven by rapid progress of experimental methods for data generation, which required adequate computational methods for data processing and quality control, prompted epigenome prediction studies as a means of understanding the genomic distribution of epigenetic information, and provided the foundation for initial projects on cancer epigenetics. While these topics will continue to be major areas of research and the mere quantity of epigenetic data arising from epigenome projects poses a significant bioinformatic challenge, several additional topics are currently emerging.

- Epigenetic regulatory circuitry: Reverse engineering the regulatory networks that read, write and execute epigenetic codes.

- Population epigenetics: Distilling regulatory mechanisms from the integration of epigenome data with gene expression profiles and haplotype maps for a large sample from a heterogeneous population.

- Evolutionary epigenetics: Learning about epigenome regulation in human (and its medical consequences) by cross-species comparisons.

- Theoretical modeling: Testing our mechanistic and quantitative understanding of epigenetic mechanisms by in silico simulation.[5]

- Genome browsers: Developing a new blend of web services that enable biologists to perform sophisticated genome and epigenome analysis within an easy-to-use genome browser environment.

- Medical epigenetics: Searching for epigenetic mechanisms that play a role in diseases other than cancer, as there is strong circumstantial evidence for epigenetic regulation being involved in mental disorders, autoimmune diseases and other complex diseases.

Epigenetics Databases

- MethDB[6] Contains information on 19,905 DNA methylation content data and 5,382 methylation patterns for 48 species, 1,511 individuals, 198 tissues and cell lines and 79 phenotypes.

- Pubmeth[7] Contains over 5,000 records on methylated genes in various cancer types.

- REBASE[8] Contains over 22,000 DNA methyltransferases genes derived from GenBank.

- DeepBlue Epigenomic Database[9] contains epigenomic data from more than 60,000 experiments from different IHEC members files divided in many different epigenetic marks. DeepBlue also provides an API for access and process the data on the server.

- MeInfoText[10] Contains gene methylation information across 205 human cancer types.

- MethPrimerDB[11] Contains 259 primer sets from human, mouse and rat for DNA methylation analysis.

- The Histone Database[12] Contains 254 sequences from histone H1, 383 from histone H2, 311 from histone H2B, 1043 from histone H3 and 198 from histone H4, altogether representing at least 857 species.

- ChromDB[13] Contains 9,341 chromatin-associated proteins, including RNAi-associated proteins, for a broad range of organisms.

- CREMOFAC[14] Contains 1725 redundant and 720 non-redundant chromatin-remodeling factor sequences in eukaryotes.

- The Krembil Family Epigenetics Laboratory[15] Contains DNA methylation data of human chromosomes 21, 22, male germ cells and DNA methylation profiles in monozygotic and dizygotic twins.

- MethyLogiX DNA methylation database[16] Contains DNA methylation data of human chromosomes 21 and 22, male germ cells and late-onset Alzheimer's disease.

Sources and further reading

- The original version of this article was based on a review paper on computational epigenetics that appeared in the January 2008 issue of the Bioinformatics journal: Bock C, Lengauer T (January 2008). "Computational epigenetics". Bioinformatics. 24 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btm546. PMID 18024971.. This review paper provides >100 references to scientific papers and extensive background information.

References

- ↑ Bock C, Lengauer T (January 2008). "Computational epigenetics". Bioinformatics. 24 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btm546. PMID 18024971.

- ↑ Madrigal P, Krajewski P (July 2015). "Uncovering correlated variability in epigenomic datasets using the Karhunen-Loeve transform". BioData Mining. 8: 20. doi:10.1186/s13040-015-0051-7. PMC 4488123. PMID 26140054.

- ↑ Shi SP, Qiu JD, Sun XY, Suo SB, Huang SY, Liang RP (April 2012). "PLMLA: prediction of lysine methylation and lysine acetylation by combining multiple features". Molecular BioSystems. 8 (5): 1520–1527. doi:10.1039/C2MB05502C. PMID 22402705. S2CID 6172534.

- ↑ Zheng H, Jiang SW, Wu H (2011). "Enhancement on the Predictive Power of the Prediction Model for Human Genomic DNA Methylation". Biocomp'11: The 2011 International Conference on Bioinformatics and Computational Biology. S2CID 14599625.

- ↑ Roznovăţ IA, Ruskin HJ (September 2013). "A computational model for genetic and epigenetic signals in colon cancer". Interdisciplinary Sciences, Computational Life Sciences. 5 (3): 175–186. doi:10.1007/s12539-013-0172-y. PMID 24307409. S2CID 11867110.

- ↑ DNA Methylation Database

- ↑ Pubmeth.Org

- ↑ "Official REBASE Homepage | the Restriction Enzyme Database | NEB".

- ↑ "DeepBlue Epigenomic Data Server".

- ↑ "MeInfoText: associated gene methylation and cancer information from text mining". Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2010-01-29.

- ↑ "methPrimerDB: the DNA methylation analysis PCR primer database". Archived from the original on 2014-07-15. Retrieved 2010-01-29.

- ↑ "Histone Database - Histone Database". Archived from the original on 2015-09-05. Retrieved 2010-01-29.

- ↑ "ChromDB::Chromatin Database". Archived from the original on 2019-04-10. Retrieved 2010-01-29.

- ↑ Cremofac

- ↑ "Home". epigenomics.ca.

- ↑ Methylation Database Archived 2008-12-03 at the Wayback Machine