The colonial architecture of Brazil is defined as the architecture carried out in the current Brazilian territory from 1500, the year of the Portuguese arrival, until its Independence, in 1822.

During the colonial period, the colonizers imported European stylistic currents to the colony, adapting them to the local material and socioeconomic conditions. Colonial buildings with Renaissance, Mannerism, Baroque, Rococo and Neoclassical architectural traits can be found in Brazil, but the transition between styles took place progressively over the centuries, and the classification of the periods and artistic styles of colonial Brazil is a matter of debate among specialists.

The importance of the colonial architectural and artistic legacy in Brazil is attested by the ensembles and monuments of this origin that have been declared World Heritage Sites by UNESCO. These are the historic centers of Ouro Preto, Olinda, Salvador, São Luís do Maranhão, Diamantina, Goiás Velho, the Ruins of the Guarani Jesuit Missions in São Miguel das Missões, the Bom Jesus de Matosinhos Sanctuary in Congonhas, and São Francisco Square in São Cristóvão. There are also the historical centers that, although they have not been recognized as World Heritage Sites, still have important monuments from that period, such as Recife, Rio de Janeiro, and Mariana. Especially in the case of Recife, the demolition and decharacterization of most of the historic buildings and the colonial urban layout were decisive for the non-recognition.

Colonial settlements and urbanism

.jpg.webp)

Architectural activity in colonial Brazil begins in the 1530s, when colonization gains momentum with the creation of the Captaincies of Brazil (1534) and the foundation of the first villages, such as Igarassu and Olinda, founded by Duarte Coelho around 1535, and São Vicente founded by Martim Afonso de Sousa in 1532. Later, in 1549, the city of Salvador was founded by Tomé de Sousa as the seat of the General-Government. The architect brought in by Tomé de Sousa, Luís Dias, then designs the capital of the colony, including the governor's palace, churches and the first streets, squares and houses, in addition to the indispensable fortification around the settlement.[2][3][4]

The noblest part of the city of Salvador, which included rammed earth buildings such as the governor's palace, residences and most of the churches and convents, was built on high ground, 70 meters above the beach level; while, by the bay, the infrastructure dedicated to commercial activities was built. Other cities founded in the 16th century, such as Olinda (1535) and Rio de Janeiro (1565), are characterized by having been founded near the sea but on land elevations, dividing the settlement into a high town and a low town. In general, the upper town was home to the residential and administrative areas and the lower part to the commercial and port areas, resembling the organization of the main Portuguese cities, such as Lisbon, Porto, and Coimbra, from ancient and medieval times. This arrangement obeyed defense considerations, since in the early days the colonial settlements were at constant risk of attacks from indigenous peoples and Europeans from other nations. In fact, almost all the first settlements founded by the Portuguese had walls, palisades, bastions, and gates that controlled access to the interior.[5]

Colonial urbanism in Brazil was often characterized by the adaptation of the layout of streets, squares and walls to the relief of the terrain and position of important buildings such as convents and churches. Although they did not follow the rigid checkerboard pattern of Spanish foundations in the New World, many colonial cities, starting with Olinda and Salvador, are now considered to have had their streets laid out with relative regularity.[7][8] During the period of the Iberian Union (1580–1640), cities founded in Brazil had greater regularity, as is the case of Felipeia da Paraíba (now João Pessoa), founded in 1585, and São Luís do Maranhão, laid out in 1615 by Francisco Frias de Mesquita, with the trend towards regularity of urban center layouts increasing throughout the 17th century.[5] Also noteworthy are the great urbanistic works carried out in Recife during the government of Count John Maurice of Nassau (1637–1643), who, with the embankment and construction of bridges, canals, and forts, transformed the old port of Olinda into a city.

A determining aspect of colonial urbanism was the establishment of churches and convents. Often the construction of religious buildings was accompanied by the creation of a churchyard or a square next to the building, as well as a network of access streets, organizing the urban space. In Salvador, for example, the construction of the Jesuit College in the 16th century, outside the city walls, gave rise to the Terreiro de Jesus Square and made the area a pole of expansion of the city. Another notable example of colonial urban space is the Pátio de São Pedro, which arose from the construction of the São Pedro dos Clérigos Co-Cathedral in Recife (after 1728). In Rio de Janeiro, the main colonial street, Direita Street (currently Primeiro de Março Street), arose as a connection between the Morro do Castelo, where the city was founded, and the São Bento Monastery, located on the hill of the same name. Another important aspect was the establishment of religious monuments in high places, sometimes preceded by staircases, which created scenographic landscapes with a strong baroque character. In Rio, for example, many monasteries and churches were built on hills, with their facades facing the sea, offering a magnificent setting for travelers entering Guanabara Bay. The privileged relationship between topography and churches is also striking in the cities of Minas Gerais, especially Ouro Preto and the Congonhas Sanctuary. In the latter, the pilgrimage church is located on top of a hill, preceded by a set of chapels with the Via Sacra and a staircase decorated with statues of prophets.

In the 18th century, reforms carried out by the government of the Marquis of Pombal, linked in part to the need to occupy the limits with Spanish America, led to a greater presence of military engineers in the colony and to the foundation of several planned vilas, in which the places for administrative buildings, churches, and symbols of public power were planned. Thus, during the 18th century, many villages were created with planned urbanism in the current states of Rio Grande do Sul, Mato Grosso, Goiás, Roraima, Amazonas and others. Moreover, in some places common facade patterns for buildings were adopted with the aim of creating a harmonious urban ensemble, as observed in the lower city of Salvador in the mid-eighteenth century.[5] In Minas Gerais, where the gold rush favored the rapid growth of villages in hilly terrain without any planning, there were also some important urbanistic interventions. The layout of the city of Mariana, located on relatively flat terrain, was regularly remodeled in 1745 by José Fernandes Pinto Alpoim. At the same time, several houses were demolished in downtown Ouro Preto for the creation of a monumental square, today known as Tiradentes Square, where the City Council House and the Governor's Palace were built. Urban improvements were more frequent as colonization advanced. In Salvador, major landfills in the 18th century allowed the development of the lower city, previously restricted to a narrow strip of land. In Rio de Janeiro, lagoons and swamps were filled in to allow expansion and improve the salubrity of the city.

Also in Rio was built perhaps the largest infrastructure work in colonial Brazil: the Carioca Aqueduct, definitively inaugurated in 1750. The aqueduct brought water from the river of the same name to the city center, feeding several fountains, some of which still exist. One of them was located in Paço Square (now 15 November Square), urbanized in the early 1740s by José Fernandes Pinto Alpoim in the image of Lisbon's Ribeira Square. The square's pier would later gain a monumental fountain, designed by Mestre Valentim and completed in 1789.

Rio de Janeiro, capital of the colony since 1767, was the main focus of urban interventions between the 18th and 19th centuries. The most important was the creation of the Passeio Público between 1789 and 1793. The design of the park, executed according to a project by Mestre Valentim, included geometric tree-lined boulevards, fountains and statues. To build the park required a major urban intervention, with the destruction of a hill and the embankment of a pond. Later, with the arrival of the Portuguese royal family in 1808, Rio also gained the Botanical Garden, the first in Colonial Brazil.

Architects

Those responsible for the architectural designs (riscos) of the colony remained largely anonymous, even in the case of some large convents and churches. Among the known authors, there are religious and many military engineers, the latter with solid theoretical knowledge of architecture. Others had more practical knowledge, such as master builders, master stonemasons and carpenters.

Religious orders such as the Jesuits, Benedictines, Franciscans and Carmelites, among the first to settle in Brazil, had notable architects and builders in their ranks, and with them began a great tradition of increasingly rich and imposing religious buildings. For example, the Jesuit architect Francisco Dias, who had worked on the construction of the Jesuit church in Lisbon, arrived in Brazil in 1577. He worked on the Graça Church in Olinda (his only design still standing), and built the Jesuit colleges in Rio de Janeiro, Santos, and others. Another important religious architect was Friar Macário de São João, a Benedictine to whom are attributed the 17th century designs of the churches of the São Bento Monastery and the Misericórdia of Salvador, among others.[9]

The military engineers were mostly Portuguese, with some of other nationalities, especially Italians in the service of Portugal. These engineers not only built forts, but were also responsible for delineating settlements and designing administrative buildings and even religious constructions. A prominent example in the 17th century was Francisco Frias de Mesquita, who was in Brazil between 1603 and 1635 and built several forts, delineated the city of São Luís do Maranhão (after 1615) and designed the church of the São Bento Monastery of Rio de Janeiro (1617).[10]

Throughout the 18th century, Portuguese military engineers designed some of the most important works of colonial architecture. José Fernandes Pinto Alpoim, for example, designed in Rio de Janeiro the Imperial Palace, the Convent of Santa Teresa, urbanized the Paço Square and finished the work of the Carioca Aqueduct. In Minas Gerais, he designed the Governor's Palace in Ouro Preto and delineated the city of Mariana. In Rio, the Candelária Church was designed by Francisco João Roscio, another Portuguese military engineer. In Ouro Preto, Pedro Gomes Chaves designed the Nossa Senhora do Pilar Parish Church, while in Bahia, Manuel Cardoso de Saldanha designed the remarkable Nossa Senhora da Conceição da Praia Basilica, with an innovative plan and facade. Of course, Portuguese military engineers also built fortresses. In the south, for example, José da Silva Pais built an elaborate system of forts to defend the Santa Catarina Island.

The growing need for skilled professionals in the colonies led the colonial government to create the so-called Military Fortification and Architecture Classes (Aulas de Fortificação e Arquitetura Militar), which represent the first schools dedicated to teaching architecture in Brazil. The first one was created in Salvador in 1699, along with the one in Recife at the same time. In 1735, a Class was created in Rio de Janeiro, in which the aforementioned Pinto Alpoim was the first teacher. From these classes the first military engineers graduated in Brazil began to emerge. One outstanding example was José António Caldas (1725–1767), born in Bahia and a student of Manuel Cardoso de Saldanha at the Class of Salvador. He worked on several engineering and architectural projects in the northeast, including the renovations of the Salvador Cathedral (already demolished). He was also sent to the west coast of Africa to perform engineering tasks. From 1761, he was a professor at the Class of Salvador, in which he had graduated.[11][12]

Other important groups were the master builders and master stonemasons, who in principle were responsible for the execution of the works, also often designed architectural projects. These professionals had no theoretical training in architecture but had much practical knowledge, acquired on the construction sites. Among these professionals who created notable architectural designs is Manuel Ferreira Jácome, master stonemason, author of the São Pedro dos Clérigos Co-Cathedral. In Minas Gerais the presence of these masters was very striking and included names such as José Pereira dos Santos, José Pereira Arouca and Francisco de Lima Cerqueira, the latter responsible for the Saint Francis of Assisi Church in São João del-Rei.

There were also designers who were not builders. An important example was Antônio Pereira de Sousa Calheiros, who was a doctor in law but designed the Rosary Churches in Ouro Preto and in Mariana. Luís da Cunha Meneses, colonial governor, designed the monumental City Council House and Jail of Ouro Preto. It is also important to mention Antônio Francisco Lisboa, Aleijadinho, who was primarily a sculptor but also author of important architectural projects.

Techniques and materials

Walls

Initially, the colonial architecture used the techniques of rammed earth and wattle and daub, of quick construction and using abundant materials in the colony: clay and wood. Soon stonemasonry or adobe bricks were also adopted to raise walls, which allowed the construction of larger structures and the inclusion of woodwork for floors and ceilings.[13]

Wattle and daub, also called "taipa de sebe", "taipa de mão", "taipa de sopapo", or "barro armado", was one of the most used building systems in the colonial period. This was due to its low cost, since all of its required materials are natural, as well as its good resistance and durability. It was well known by the indigenous and African people, and its greatest incidence was in the areas that correspond to the current Northeast and Southeast regions. Its purest version has as its main structure wooden pieces composed of upper horizontal pieces (frechais), lower horizontal pieces (baldrames), and vertical pieces (esteios). The pieces are joined to form a weft, tied by silk, linen, hemp, or buriti cords. Finally, the clay is thrown on top.[13]

One system, similar to wattle and daub is the timber framing, common in the southern region, which, however, uses masonry for the fence.[13]

Another widely used system, especially for internal partitions is the tabique, which consists of a structure of wooden beams covered by boards. It is a system of great ease and simplicity in its execution. For the systems, the most commonly used woods at the time were aroeira, braúna, ipê, peroba, jatobá, among others.[13]

In Brazil the use of rammed earth also became popular, basically because it responded positively to the challenges of the time, because when well used it has a low energy consumption in the manufacturing process. The raw materials used in the production of rammed earth blocks are easily accessible and most of the time no transportation is required. In addition to this characteristic, rammed earth has a great thermal inertia, ideal for the climate of the Brazilian coast, and allows moisture exchange with the external environment.[14]

Stonework was used in the noblest buildings, usually as reinforcement in the corners (cunhais) of large buildings and in the lintels of portals and windows. Very few buildings were built exclusively in stonework, a preserved example being the Garcia d'Ávila Tower House in Bahia, mostly built in the early 1600s. Even in the following centuries few churches were built with stone facades.

In the beginning, stonemasonry was mainly used to build fortifications on dry stones, without leveling, to provide more solidity to the buildings to resist the constant indigenous attacks, like the ancient Reis Magos Fortress in Natal.[2][15] With the arrival of the Jesuit company in Brazil, the use of stone and lime – stonemasonry fitted with lime and sand mortar – was encouraged as a construction method, in the manner of the Portuguese architecture.

In the construction of the new Jesuit monuments on the coast, it was common to use the stone of the realm, the lioz, a kind of semi-marble, imported from Portugal already cut, which was brought as ballast in Portuguese ships, and was fully employed in the Nossa Senhora da Conceição da Lapa Convent.[16] As coastal cities and of greatest importance for the colony, Rio de Janeiro, Salvador and Recife enjoyed this luxury, while in more inland regions it was necessary to exploit the raw material of local abundance, so that sandstone is widely seen applied in masonry with clay mortar, not only in public or religious buildings, but also in housing.[16]

Roofs

In the early days, the roofs of the houses were simply made with straw (sapé), like the indigenous huts (ocas) or certain African-influenced dwellings, still existing today in rural areas. The clay (ceramic) roof tile was initially used in the wealthier buildings before becoming popular.

Among the types of tile used in the period are:[13]

- canal tiles, also called colonial tiles, cape and canal, cape and spout, "made on the thighs"; outside Brazil, they are known as Arab or Moorish tiles;

- French tiles, or marselha;

- Roman tiles.

There were various types of roof truss, made of wood, sometimes supplemented by rafters. An important element of the roofs were the eaves, which protected the mud walls from rainwater. It was common for the rafters under the eaves to be carved as ornamentation, and called modillions. There were also elements that complemented or worked as an extension to the main roofs: the balconies and porches. Finally, the ceiling linings in general were flat.[13]

Frames

Doors and windows (leaves) were made of wood, similar to contemporary ones. There were leaves made of rulers (straight lintels), of cushions, of lattices (urupemas), of wooden lace, with wickets, etc. More recently, pine leaves (with spaces for glass) appeared, which replaced blind leaves.[13]

The leaves had several modes of operation:[13]

- horizontal opening, or French-style, now called tilt-and-turn;

- vertical opening, called gelosias or rótulas;

- guillotine or English-style opening.

In the case of thick walls, it was common to chamfer (cut) the wall around the window. The larger opening space obtained increased the room's luminosity, and could be used for seating (conversation chairs). Among additional elements were parapets, balconies, muxarabis, arrowslit, door knockers, etc.[13]

Floors

Internal floors could be dirt floors, clay tile floors, plank floors (floorboards, especially on raised floors), or slab floors (of marble, in the case of noble buildings).[13]

Among the external ones were:[13]

Others

The paintings on the walls were usually whitewashed, made with lime obtained from shellfish, stone or tabatinga (a white clay). The wood, on the other hand, was painted with glue, tempera, or oil. Among the dyes used were indigo (blue), dragon's blood and urucum (red), safflower (yellow), braúna (black), ipê and cochineal (pink).

The foundations were generally direct (shallow), made of stonemasonry. However, in the wattle and daub and timber framing buildings, there were fire-treated wooden struts buried 2 to 4 m deep.[13]

Religious architecture: Mannerism and Portuguese Plain Style (XVI-XVII centuries)

The first religious temples built in Brazil followed the Portuguese late Renaissance or Mannerist style, known as the Portuguese Plain Style. This aesthetic is characterized by facades composed of basic geometric figures, triangular pediments, windows close to the square, and walls marked by the contrast between stone and white surfaces, with a two-dimensional aspect.[17] The decoration is scarce and generally limited to the portals, although the interiors are rich in altars, paintings, and tiles.

Thus, the first Brazilian churches have nave and chancel with rectangular shapes, one or three naves, simple windows and a rectangular or square facade topped by a triangular pediment. They may also have one or two side towers. Throughout the 17th century, fronts adorned with volutes of a Mannerist nature appear. In this first phase, the main models of colonial churches were São Roque Church and of São Vicente de Fora Monastery in Lisbon.

Today there are few examples of 16th century architecture left in Brazil, since most of the older buildings have either been destroyed or greatly altered. Rare examples of religious architecture from the 16th century are the São Cosme e São Damião Mother Church in Igarassu (begun in 1535 and later renovated) and the Graça Church in Olinda, built in the last quarter of the 16th century, with a Mannerist facade inspired by the São Roque Church in Lisbon. The architect of the latter, Brother Francisco Dias, had worked on the construction of the Lisbon church and designed other Jesuit churches in Brazil with similar architecture.[18][19]

Since the 16th century, the Jesuits built churches and colleges in isolated regions to promote the conversion of the indigenous people to Christianity. Some important examples of Jesuit churches from the early days of colonization are those in São Pedro d'Aldeia (RJ), Nova Almeida (ES), Embu (SP), and the São Miguel Chapel in São Miguel Paulista (SP), all dating from the 17th or early 18th century.[9][18] In the metropolis of São Paulo, which arose around a Jesuit village, the 16th century facade of the former Jesuit church and college (known as Pátio do Colégio) was faithfully reconstructed based on ancient iconography. The facade shows the 16th century traces of the early floor style, including a triangular pediment. In contrast, in Rio de Janeiro, the important Jesuit church on Morro do Castelo, founded in 1567, was demolished in 1922 in the redevelopment of the area where it was located.[20] Similar to those in São Paulo and Rio were the Jesuit church and college in Santos,[19] demolished in the 19th century but well known from plans and drawings.

Several churches from the 17th century, of a Mannerist character, still survive in Brazil. One example is the church of the São Bento Monastery in Rio de Janeiro, built between 1633 and 1677 based on a design from 1617. The facade is composed of geometric shapes, with a triangular pediment, flanked by two towers and with a galley with three portals, similar to the Monastery of São Vicente de Fora in Lisbon. A later example is the former Jesuit church, now Cathedral Basilica of Salvador, dated 1652–1672,[11] with a Mannerist facade topped by volutes and with two towers, features similar to the Jesuit church of Coimbra (now Sé Nova de Coimbra Cathedral).[21] The interior, with a single nave with side chapels and shallow transept and chancel, is based on São Roque Church in Lisbon. The Jesuit church in Salvador would inspire others in the region, such as the church of the São Francisco Church and Convent of Salvador.[22]

Around the middle of the 17th century, new churches appeared, and although they do not have curved Baroque plans, they present scenographic main facades, which escape from the previous rigid forms. An important example is the Santo Antônio Convent and Church of Cairu, in Bahia, built in 1654. The church entrance is preceded by a galilee formed by five arches, with two staggered upper stories flanked by volutes. The pediment of the church on the third floor contains a niche with the image of St. Anthony, and the church's single tower is set back from the facade. This facade scheme, whose Mannerist prototype could be the Franciscan church in Ipojuca, was used in the Northeast,[23] giving rise, among others, to the churches of the Franciscan convents of Paraguaçu (Bahia), Olinda, Igarassu (Pernambuco) and João Pessoa (Paraíba), the latter built in the 18th century with a richly decorated facade. The northeastern Franciscan convents were organized around a noble two-story cloister (dating already from the 18th century), of Tuscan order, often decorated with Portuguese tiles. In front of the convents, a wide churchyard with a cross increased the imposing and urbanistic importance of the ensemble. The various characteristics in common led some authors to consider the northeastern Franciscan convents to form an architectural "school", the so-called Northeastern Franciscan School (Escola Franciscana do Nordeste).[24][25]

In Salvador, in the second half of the 17th century, some majestic conventual churches were built, whose design is attributed to Friar Macário de São João: the São Bento Monastery and the Santa Tereza Convent, the latter very similar to the Remédios Convent in Evora, Portugal.[26] These churches have a single nave with a dome over the transept, an architectural model little used in colonial Brazil.

Religious architecture: Baroque and Rococo (XVIII century)

In architecture, the Baroque uses the motifs derived from classical architecture but combines them in a dynamic way, seeking to create illusionistic and scenographic effects on facades and interiors. In Europe, especially in Italy and in Germanic countries, Baroque buildings are characterized by curvilinear and undulating facades and plants. In colonial Brazil, architectural Baroque arrived late, reflecting the late adoption of the style in the metropolis itself.[27] Curves or undulations in facades and floor plans were rare.

The importance of carving and painting

The interiors of colonial churches should be seen not only in architectural but also decorative terms, as the internal environments were often defined by the harmonious interplay of gilded woodcarving, painting, and azulejos, typical of Portuguese art.[17]

Before influencing architecture, the Baroque style arrived in colonial Brazil in the mid-17th century in the form of gilded carved altarpieces of the so-called Portuguese National Style. This style is characterized by altarpieces formed by concentric arches with a dense sculptural load, vegetal motifs and angels, often supported by Solomonic columns. The carving was not restricted to the altarpieces, but often covered all the surfaces of the churches and chapels, and could be enriched by paintings and tiles. An important example is the Mannerist church of the São Bento Monastery in Rio de Janeiro, whose interior was completely covered with Baroque carving from the last decades of the 17th century.

Already in the first half of the 18th century, the Golden Chapel of the Third Order of St. Francis in Recife was completed and most of the decoration of the São Francisco Church in Salvador was executed. Both are integrally covered with carving, paintings and tiles. In the 1720s the Portuguese National Style carving was succeeded by the Joanine style, strongly influenced by Roman Baroque, whose pioneering example in Brazil (1726–1740) is the one integrally covering the interior of the Third Order of São Francisco da Penitência Church in Rio de Janeiro. An early example in Minas Gerais is the Our Lady of the Pillar Mother Church in Ouro Preto, with magnificent Joanine carving in the nave and chancel dating from the 1730s–50s.

In the middle of the century the carving evolved to Rococo forms, in which the ornaments are more delicate, not covering the entire available surface of the interiors. During this phase, sculptors such as Antônio Francisco Lisboa (Aleijadinho), Valentim da Fonseca e Silva (Mestre Valentim) and many others shined. At the end of the colonial phase, the carving already begins to adopt neoclassical forms.

Painting, especially the perspective painting of illusionist nature, also played an important role in interior decoration, particularly in the wooden ceilings of the naves. The earliest one in Brazil was the already mentioned Third Order of São Francisco da Penitência Church in Rio (Caetano da Costa Coelho, 1736–1743). Other famous later examples are the paintings on the linings of the Nossa Senhora da Conceição da Praia Basilica, in Salvador (José Joaquim da Rocha, after 1772) and the São Francisco de Assis Church in Ouro Preto, by Mestre Ataíde (1801–1812).

Imported azulejos from Portugal also played an important role in the interior decoration of churches in the Northeast and Rio de Janeiro. Not in Minas Gerais, due to the fragility and high cost of shipping.

Religious Baroque on the seaside

Throughout the 18th century, the overwhelming majority of religious buildings in Brazil, as well as in Portugal, continued to use the rigid floor plans linked to the Mannerist Plain Style, with naves and chapels of rectangular or square shape, without any kind of movement as curved or polygonal plans. In all of Colonial Brazil, the number of churches with Baroque floor plans that depart from the traditional Plain Style, is less than twenty. These churches are located in a few places: Recife and Salvador, with one each, and Rio de Janeiro and some vilas in Minas Gerais, with the rest.

In the other churches of the 18th century, the Baroque style was restricted to the decorative motifs of the facades and interiors, with many examples throughout Brazil. Among these, an unusual example is the Third Order of São Francisco Church, in Salvador, built in 1703 with a completely carved facade in the Churrigueresque Baroque style of the Hispanic America churches.[28] The style of this facade, however, was not continued in other buildings.

One of the first churches with a Baroque-influenced plan in colonial Brazil is the Glória Church in Rio de Janeiro, probably built in the 1730s and attributed to the military engineer José Cardoso Ramalho based on oral tradition. The church has the form of two elongated and juxtaposed octagonal prisms, with the single tower situated in front. At the base of the tower is a small portico with arcades where the main entrance is located. The plan is absolutely original, both for Brazil and Portugal, and is a true landmark in Luso-Brazilian architecture.[17] Another important church in Rio de Janeiro, unfortunately demolished in the 20th century, was the São Pedro dos Clérigos Church, dated 1733–1738. This church had an elliptical nave flanked by curved apses. The facade, curved, was flanked by two circular towers. São Pedro dos Clérigos in Rio was the first with these characteristics built in Brazil, and probably influenced the elliptical plans of certain churches from Minas Gerais built later. In Rio de Janeiro, also the churches of Conceição e Boa Morte (finished in 1758), Nossa Senhora Mãe dos Homens (begun in 1752), and Lapa dos Mercadores (built in 1747), have plans that incorporate elliptical or polygonal segments.[17]

Another notable monument of the period is the São Pedro dos Clérigos Co-Cathedral in Recife, built between 1728 and 1782 and designed by Manuel Ferreira Jácome. The interior of the church nave is octagonal in shape, like that of Glória in Rio, but the exterior is rectangular in plan, hiding the interior organization.[29] In Salvador, in 1739, construction began on the imposing Nossa Senhora da Conceição da Praia Church, designed by military engineer Manuel Cardoso de Saldanha in Portugal. The corners of the nave are chamfered, giving the interior a polygonal shape, similar to Portuguese churches such as the Menino Deus Church in Lisbon (1711). The two towers on the facade are arranged diagonally, following the shape of the nave. The stones for the church were cut in Portugal and shipped to Salvador with the master in charge of directing the construction.[30]

After the Great Lisbon earthquake of 1755, the reconstruction of Lisbon organized by the Marquis of Pombal was guided by a late Baroque classicizing style, known today as Pombaline style. This style was strongly influenced by Roman Baroque, favored by the Lisbon court since the reign of King João V (1707–1750).[27] In Brazil, the Pombaline style was reflected especially in Belém do Pará and Rio de Janeiro, which were important administrative cities in constant contact with the metropolis.[31] In Belém, the Pombaline influence is revealed in the work of the Italian architect Giuseppe Antonio Landi, for example in the churches of São João and of Santana, in the capital of Pará. In Rio de Janeiro, the oldest example is the Third Order of Carmo Church, built between 1755 and 1770. The stonework facade, the sinuous pediment, and the windows and portals, the latter imported from Lisbon, are indicative of the style. Other Carioca churches influenced by the Pombaline style are São Francisco de Paula and Candelária.[17]

Religious Baroque in Minas Gerais

In Minas Gerais, the gold rush favored construction activity throughout the 18th century, giving rise to some of the most interesting Brazilian colonial architectural monuments. As in other regions, almost all churches were built following Plain Mannerist plans, such as the Cathedral of Mariana, built in the first half of the 18th century, which in addition to the rectangular plan has a two-dimensional facade with a triangular pediment, reminiscent of the Jesuit temples of the previous century.

Very innovative is the Our Lady of the Pillar Mother Church in Ouro Preto, completed around 1733 according to the project of the military engineer Pedro Gomes Chaves. The interior of the church has a decagonal shape given by the exuberant gilded carving by Antônio Francisco Pombal, giving this church a bold internal organization. The decagonal shape is integrally given by the interior carving: externally the church presents a rectangular shape.[32]

Later on, even bolder churches appeared, such as the Nossa Senhora do Rosário dos Pretos Church in Ouro Preto (begun in 1757) and the São Pedro dos Clérigos Church in Mariana, both designed by Antônio Pereira de Sousa Calheiros. The plans of these churches, without exact parallels in Portuguese architecture of the time, are formed by three juxtaposed ellipses flanked, in the case of the Ouro Preto church, by circular towers. The entrance is made by a curvilinear galley of three arches. It is likely that the church plan was conceived under the influence of the São Pedro dos Clérigos Church in Rio de Janeiro, begun two decades earlier. The influence of Central European buildings is also possible, through engravings of architectural treatises that circulated in Minas Gerais in the 18th century.[33]

Rococo on the seaside

.jpg.webp)

Rococo, considered by many authors as the final phase of Baroque, is a decorative style of French origin that spread throughout Europe from the first half of the 18th century. It is characterized by the use of specific decorative motifs, often asymmetrical, among which the rocalhas, abstract shell-shaped motifs, stand out. In gilded carving, rococo shows more elegance and lightness than the heavy baroque carvings: while in baroque there was a tendency to horror vacui, in rococo the decorative motifs are dispersed over the surfaces.

In colonial Brazilian architecture, Rococo influences the art of the last half of the 18th century and the beginning of the next. In some churches of Rococo influence in Brazil, particularly in Minas Gerais, the facades have three-dimensional effects created by the receding and rotating position of the towers and the undulations of the surfaces. In most cases, however, rococo was restricted to the decorative motifs of the facades, particularly in the design of the pediments, cornices, and bulbous domes of towers.

In Recife there is an important set of facades of Rococo influence, such as the Nossa Senhora do Carmo Basilica and Convent, begun in 1767, the Santo Antônio Mother Church and others, all with curved cornices and exuberant pediments. In Bahia there are also several facades with Rococo details, such as the pediment of the Nosso Senhor do Bonfim Church, also dating from the last quarter of the 18th century. In Rio de Janeiro, on the other hand, the Rococo style was restricted to the decoration of the interiors, as in the Santa Rita Church and the Old Cathedral.[17]

Rococo in Minas Gerais

In Minas Gerais, religious architecture followed different paths during the Baroque-Rococo period. Unlike the other regions of Brazil, the facades of some churches incorporated three-dimensional variations, creating a new expressiveness. In addition, the availability of soapstone (steatite), an easy material to carve, allowed the development of beautiful and original portals by the greatest colonial sculptor, Antônio Francisco Lisboa, Aleijadinho.

In the Santa Efigênia Church in Ouro Preto, begun in 1733 and possibly designed by Manuel Francisco Lisboa, one observes the slightly recessed positioning of the towers in relation to the façade, in addition to a slight rounding of the towers, which can be seen as a precursor of future facades in Minas Gerais.[34] The facade of the Congonhas Sanctuary (begun in 1757) incorporates a beautiful carved portal in soapstone dated between 1765 and 1769 and probably by Jerônimo Félix Teixeira. The importance of this gateway lies in the fact that it is the first of a long series of rococo style carved gateways in the Minas Gerais region.[35]

The Nossa Senhora do Carmo Church in Ouro Preto, begun in 1766, is a landmark of Minas Gerais' Rococo style. The facade is wavy and has a cornice of semicircular shape, which encompasses a trilobed lobe typical of Rococo. The towers, set back from the façade, are semicircular in shape. The church was originally designed by Manuel Francisco Lisboa, but the facade was reformulated around 1770 by a team that included Francisco de Lima Cerqueira and Aleijadinho. The latter created the cartouche of the doorway, in which the shield of the Carmelites is surrounded by stones and held by two winged angels. The theme of little angels and rocalhas, which had been debuted by Aleijadinho shortly before in the doorway of the Carmo Church in Sabará, would be a constant in the portals designed by the artist.[36]

Perhaps the most important of the Minas Gerais churches of this phase is the Third Order of São Francisco Church in Ouro Preto, a landmark of Luso-Brazilian architecture begun around 1765. The exceptional façade of this church incorporates circular towers, set at an angle to the facade and crowned by bulbous domes. The central body of the facade and the recessed towers are separated by a concave segment, creating a beautiful three-dimensional effect. The central body of the facade is delimited by two columns supporting pediment fragments, also with rotating movement. In general, the organization of the facade belongs more to the late Baroque than to the Rococo and has no clear Portuguese antecedents, perhaps inspired by central European engravings. Although the design of the façade is traditionally attributed to Aleijadinho, this is not confirmed by any document.[37][38] What is indeed of Aleijadinho's authorship is the doorway in soapstone, created in 1774 and which completes the set. On the doorway, the sculptor positioned three tablets with the Wounds of Christ, the Arms of Portugal and, on the upper level, the figure of the Virgin Mary, all intertwined with Franciscan motifs, heads of angels, asymmetric scrolls and ribbons with inscriptions. On each side of the lintel there are two angels: one holds a card and the other a cross. To complete the picture, the window at the top of the facade contains a magnificent high-relief showing St. Francis kneeling to receive the wounds. The interior of this church was entirely decorated with carvings by Aleijadinho, with an illusionist painting by Mestre Ataíde on the ceiling of the nave.

Also in 1774, Aleijadinho projected a façade for the Third Order of São Francisco de Assis Church in São João del -Rei, whose drawing is preserved in the Inconfidência Museum in Ouro Preto. In this drawing, one can see how the artist created a facade with strong Rococo characteristics, slightly sinuous like the Carmo Church in Ouro Preto, with a pediment delimited by immense rocalhas and with a high relief of St. Francis kneeling in the center. The towers would be semicircular, the cupolas bell-shaped and, in the center, there would be a decorated doorway. The project ended up being totally modified by Francisco de Lima Cerqueira, who created another pediment, added circular towers of rotating movement, endowed with a balcony, and contracted another portal to Aleijadinho, similar to that of São Francisco Church in Ouro Preto. In addition, Lima Cerqueira designed a nave with sinuous walls, giving it an elliptical shape, unheard of in colonial architecture at the time.[39]

Circular or semicircular towers (sometimes polygonal), positioned in a recessed manner in relation to the facade, were traditional in Minas Gerais, being found for example in the Barão de Cocais Mother Church (before 1785) and in the Third Order of Carmo Churches in São João del-Rei (after 1787) and in Mariana (after 1783).[39] Circular towers are absent from the architecture of the Brazilian coast and the metropolis, with the exception of the demolished São Pedro dos Clérigos in Rio.[33]

Another unique work in Minas Gerais of the period is the Bom Jesus de Matosinhos Sanctuary, in Congonhas do Campo, a local version of the Bom Jesus do Monte Sanctuary, located in Braga, in northern Portugal.[40] The complex, begun in 1757, consists of a church positioned on a hill which the faithful reach by passing through several chapels with representations of Christ's passion. In the last section there is a zigzagging staircase leading to the churchyard in front of the church. Once inside the church, one can find the image of Bom Jesus de Matosinhos, based on the image venerated in the city of the same name in Portugal. Very interesting are the churchyard and the staircase in front of the church, built between 1777 and 1790, formed by concave-convex segments, an urbanism of Baroque and Rococo decorative forms. The staircase was decorated between 1800 and 1805 by 12 large soapstone statues of Old Testament prophets, by Aleijadinho and his officers. The 6 chapels located in the first part of the sanctuary, square in plan, were also decorated with sculptural sets by Aleijadinho. The landscape set formed by the church, the churchyard with prophets and chapels is of great expressiveness, unparalleled in the colony.

Military architecture

In the early years of colonization one of the biggest concerns of the Portuguese metropolis was to secure the possession of the territory, and the first settlements were always fortified with palisaded walls and forts. The oldest fortress still standing in Brazil is São Tiago Fort (which still survives under the name São João da Bertioga Fort), in Bertioga, dating from 1532. It was at first a wooden palisade, and was later remodeled in masonry, acquiring its current configuration.[41]

Later a series of other forts were erected all along the coast, and at some points in the countryside, and they basically followed the same model that remained without much variation over the centuries, of square or polygonal plan, sometimes deformed to fit the underlying topography. They had a chamfered base in bare stone, whitewashed masonry walls on top, with guardhouses interspersed, and a series of stripped dwellings inside, often with some chapel or small temple. Occasionally more or less elaborate portals were erected at the entrance of the fortresses, following the late Renaissance or Mannerist style, which predominated during the 16th and 17th centuries. An original example is São Marcelo Fort, built on an islet in Salvador in the 1650s and the only one of circular plan in Brazil.

Civil architecture

Typology

In terms of volumetric typology, the main categories of civilian colonial buildings are shed-roofed (ranches, kitchens), gable-roofed (very common in cities), hip-roofed (larger buildings such as pavilions, townhouses, public facilities), and cloisters (ditto). An intermediate solution between the last two categories were the "L-shaped" plans.[13]

With respect to the simpler rural constructions (designated as "sertanejo" or "caboclo" houses, "mocambos", "palhoças", etc.), for free men, they generally had a vegetal covering of straw and walls of wattle and daub. They had a single room and a front veranda.[13][42][43]

On the largest rural properties, the plantations, there were three main elements: the senzala, the mill and the big house. The senzalas had a long floor plan, with several cells, made of brick masonry or wattle and daub, and with a vegetated or tiled roof. The mill consisted of a roof supported by brick pilasters, and was divided into two parts, the mill and the boiler. Finally, the big house, the headquarters of the farms, had a very varied form, presenting a single, elevated housing floor, and another lower, for warehouses and service personnel.[13][44][45] In the case of São Paulo, there is a specific type of rural construction, the bandeirista house, whose design is comparable to Palladio's plans.[13]

In the urban environment, the lot was always narrow and deep, with houses aligned at the front and terraced on both sides, which was a way to protect the walls from rainwater.[13] There was initially a fundamental distinction between sobrados (houses with two or more floors) and one-floor houses, establishing a division between rich and poor. The houses on the ground floor had hardwood floors, while the sobrados had wooden floors on their upper floors. The first floors of the sobrados, however, were also of beaten floors, being used to accommodate slaves and animals or as stores. Only in the 19th century would an intermediate type emerge, the "high basement house."[44]

A further distinction, in legal terms, was made between houses and buildings: the former were rustic, precarious, and not subject to prescriptions or rights, while the buildings, of a permanent, solid character, guaranteed certain privileges and were regulated by laws.[46]

The width of urban land, in general, varied between 4.4 m and 11 m, a size proportional to 2.2 m, that is, one fathom in length, equivalent to the measurement of the taipal then used as a model. The width of three taipals was called a haul.[47] There were three main types of dwellings, according to width: "door and window", "half dwelling" and "whole dwelling". Although initially identified in the north of the country, especially in Maranhão,[48] these three basic types are applicable to houses in other Brazilian cities in the same period.[43][47]

History

_cropped.jpg.webp)

In its early days, civil architecture – residences, mills, colonial government palaces – were also built using rammed earth techniques, often with straw roofing. As colonization progressed and a basic urban structure was established, adobe and stone masonry began to be used, with reinforced woodwork and tiled roofs.

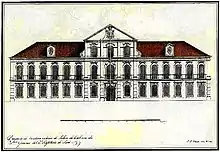

The first large-scale building in Brazil was the Fribourg Palace, the official residence built by Count John Maurice between 1640 and 1642 in Recife, then the seat of the colony of New Holland. It had two tall, square towers with five floors, connected by a covered walkway, giving it the appearance of a church. The towers, besides embellishing the palace, served as a landmark for sailors, who could see them from a distance of more than seven miles. One of them was used as a lighthouse and the other as an astronomical observatory, the first one founded in the Southern Hemisphere. Protected from a military point of view by cannons, it had a large moat and Ernesto Fort. Between 1774 and 1787, being quite ruined due to the fights against the Dutch that occurred in the previous century, it was demolished by order of the then governor José César de Meneses.[49]

One of the oldest preserved examples of civil architecture is the Garcia d'Ávila Tower House in Bahia, now in ruins. The house had its beginnings in a fortified tower built in the 1550s and enlarged in the 17th and 18th centuries in the style of the noble Portuguese stone houses.[50] The house also has a curious 16th century chapel of hexagonal shape.

In Salvador, the administrative buildings in rammed earth constructed in the 16th century in the main square were later replaced by others in stonework. The governor's palace (now lost) and the town hall were rebuilt in the second half of the 17th century. In the 1960s the town hall was renovated and returned to its original 16th century plain appearance. It is characterized by the porticoed gallery on the first floor and the tall central tower, which would influence other chambers built in colonial Bahia.[51]

.jpg.webp)

In the colony's inlands, sugar mills and farmhouses multiplied. Around São Paulo there are still several examples of 16th and 18th century rural houses, some within the São Paulo megalopolis itself, such as the so-called Sertanista House, dating from the 17th century,[52] and the Butantã's House,[53] from the mid-18th century.

Compared to previous centuries, in the 18th century the quantity and quality of civil buildings increased, although in general civil architecture produced buildings of much less size than religious architecture.

In the villages and cities most of the residences had only one floor, while the noblest ones could have a second floor – so called sobrados – or even more, reaching four floors in some important centers such as Recife, Salvador and São Luís. Houses in Brazil were generally of stone masonry or taipa de pilão with partition walls of pau a pique, with the exception of Pernambuco, where the use of brick was more common.[54] The stonemasonry, when it existed, was limited to the corners of the house. The first floor had a dirt floor, while the other floors had wooden plank floors. The first floor was used for commercial activities, storage, stables, and slave quarters, with a corridor leading to the back yard and a staircase leading to the upper floor. The second floor – the noble floor – was dedicated to housing. It was organized with a large hall facing the street, from which emerged a corridor with on each side small rooms without openings to the outside (alcoves). The profile of the windows was rectangular or arched, framed in wood or, more rarely, in stone. The noble floors could have balconies with iron railings. The upper windows could also be covered with mashrabiya or wooden lattices, while glass windows only became common in the late 18th century. The roofs were gable or hipped with eaves, sometimes with some discreet ornamentation such as a gentle curvature and pointed tiles at the corners of the roof.

Urban houses of great nobility dating from the late 17th and early 18th centuries are common, for example, in Salvador, such as the Sete Candeeiros House, the Ferrão Palace, the Saldanha Palace, the Conde dos Arcos Palace, and the imposing Arcebispos House of the city, built between 1707 and 1715. In Bahia the urban palaces are characterized by doorways in lioz stone or local stone, decorated with reliefs, coats of arms, and volutes. The interiors could be decorated with coffered ceilings and Portuguese tiles. In Rio de Janeiro, an important example is the Governors' Palace (now Imperial Palace), built between 1738 and 1743. This palace, also decorated with Lioz shutters, was the first in Brazil to present windows with curved upper lintel, which soon after would be very common throughout the colony.

Also in the hinterland farms some interesting manor houses survive. Some of great dimensions, such as the big house of the Freguesia Mill, in the Recôncavo Baiano region, although its architecture is in general quite simple, with a main building for the owner's residence and other annexes for the senzala, deposits for tools and food, shelters for animals and small houses for the farmers. A unique case in a different genre is the Carioca Aqueduct, a large civil work for conducting water, erected between the 17th and 18th centuries, located in Rio de Janeiro, 270 m long and 17 m high.

Few of the official buildings have survived without alterations. One of the most significant is the former City Council and Jail House in Ouro Preto, today the Inconfidência Museum, with a rich façade where there is a portico with columns, an access staircase, a tower, ornamental statues and a stonework structure. Also important is the Imperial Palace in Rio, former residence of the royal family.

One of the most compelling and unpassionate accounts of the civil architecture of colonial Brazil is that of the English writer Maria Graham, who was in the three main Brazilian economic centers at the time (Recife, Salvador and Rio de Janeiro). In her work "Diário de uma viagem ao Brasil e de uma estada nesse país durante parte dos anos de 1821, 1822 e 1823", are her impressions when visiting Recife, Salvador and Rio de Janeiro – fresh out of the colonial period.[55] She also wrote about the architecture of the three main Brazilian economic centers at the time (Recife, Salvador and Rio de Janeiro).

In Recife, the first city visited by Maria Graham in Brazil, the tall colonial sobrados caught her attention: "The streets are paved partly with blue pebbles from the beach and partly with red or gray granite. The houses are three or four stories high (four or five floors), made of light stone and are all whitewashed, with the door and window frames of brownstone. The first floor consists of stores or lodgings for blacks or stables, the upper floor is generally suitable for offices and warehouses. The apartments for residence are higher up, with the kitchen generally at the top. This way the lower part of the house stays cool. I was surprised to see how much it was possible to leave the house without suffering the ravages of heat being so close to the equator, but the constant sea breeze that is felt here daily at 10 am maintains a temperature under which it is always possible to exercise. (...) There can be nothing more beautiful in the genre than the vivid green panorama, with the wide river winding through it, and which can be seen on either side of the bridge, and the white buildings of the Treasury and Mint, the convents and private houses, most of which have their gardens."[55]

In Salvador, although she was delighted with the view of the city from Bay of All Saints as well as the bay from the upper city, she had a sometimes uncomplimentary account of the civil architecture: "The street which we enter through the gate of the arsenal occupies here the width of the whole lower city of Bahia, and is without any exception the dirtiest place I have been in. (...) In this street the warehouses and offices of the merchants are located, both foreign and native. The buildings are tall, but not as beautiful or as airy as those in Pernambuco. (...) I accompanied Miss Pennell on a series of visits to her Portuguese friends. (...) In the first place, the houses, for the most part, are disgustingly dirty. The first floor usually consists of cells for the slaves, stables, etc., the stairs are narrow and dark, and in more than one house, we waited in a passage while the servants ran to open doors and windows of the drawing rooms and to call to the mistresses who were enjoying their home dressing in their rooms. (...) Because of its elevation and the steepness of most of the streets, [the upper town] is incomparably cleaner than the port. The cathedral, dedicated to St. Savior, is a beautiful building and stands on one side of the square where the palace, the jail and other public buildings are."[55]

And finally, about Rio de Janeiro, which was experiencing the transformations resulting from the transfer of the Portuguese court to Brazil, she said: "I spent the day paying and receiving visits in the neighborhood. The houses are built largely like those in southern Europe. There is usually a courtyard, on one side of which is the residence. The other sides are formed by the services and the garden. Sometimes the garden is right next to the house. This is usually the case in the suburbs. In the city very few houses even have the luxury of a garden (...) Rio is a more European city than Bahia or Pernambuco. The houses are three or four stories high, with projecting ceilings, tolerably beautiful. The streets are narrow, barely wider than the Corso in Rome, with which one or two bear an air of resemblance, especially on feast days, when the windows and balconies are decorated with red, yellow or green damask bedspreads. There are two very beautiful squares, besides the Palace. One, once Roça (Rossio), now Constituição, to which a very noble appearance is given by the theater, some beautiful barracks and beautiful houses, behind which the hills and mountains dominate on both sides. The other, the Campo de Sant'Ana, is extremely extensive, but is unfinished."[55]

Neoclassical architecture: 18th and 19th centuries

Neoclassical architecture is characterized by a search for the nobility and rationality of ancient Greco-Roman architecture. Harmony is sought using classical motifs: colonnaded porticoes, use of Greek orders, symmetry in the composition, regularity in the openings, and triangular pediments. The decoration is restrained, far from the Baroque and Rococo "exaggerations".

In colonial Brazil, buildings with a certain neoclassical character have existed at least since the 18th century. As already mentioned, the Joanine and Pombaline Baroque were greatly influenced by the severe Roman Baroque classicism, having reflections in Brazil.

In Recife, the Corpo Santo Church, which had its origins in the early days of the settlement, was enlarged in the 18th century gaining a beautiful Lioz stone faCade in the neoclassical style.

In Rio de Janeiro, the Santa Cruz dos Militares Church, built in 1780 according to a project by José Custódio de Sá e Faria, and the faCade of the Candelária Church, built in 1775 by Francisco João Roscio, are examples of colonial buildings with a strong classical Pombaline influence, visible in the proportions of the facades and the use of architectural orders.

In Belém do Pará, Antônio José Landi also designed buildings of marked classical character, such as the Santana Church (1760–1782), the São João Batista Chapel (1769–1772) and the Grão-Pará General Governors' Palace (1768–1772), among others. The Santana Church, in particular, is a rare party building in colonial Brazil, with a Greek cross plan with dome.

In 1808, with the arrival of the Portuguese royal family in Brazil, the local architecture was renovated. The royal architect José da Costa e Silva, coming from Portugal, possibly built in Rio de Janeiro the São João Royal Theater, inspired by the neoclassical design of the São Carlos National Theater in Lisbon, built in 1792 by Costa e Silva himself. In Salvador, engineer Cosme Damião da Cunha Fidié designed in 1813 the city's Comércio Square, a building strongly inspired by the English neo-Palladian style, with Luso-Brazilian touches.[56]

The arrival in Brazil of the French Artistic Mission in 1816 was a crucial point in the diffusion of neoclassical ideals from the capital, encouraged by the need to reorganize Rio's urban plan after the arrival of the Portuguese royal family.[57] The architect coming with the Mission, Grandjean de Montigny, became Professor of Architecture at the Royal School of Sciences, Arts and Crafts, founded by King John IV in 1816. Still during the colonial period, Grandjean designed the Comércio Square in Rio, built between 1819 and 1820, a building with a grandiose dome centered-plan. He also designed the school's main building, inaugurated only in 1826, considered a pure expression of French neoclassicism in its design, with a symmetrical façade and a great centralized portal in Ionic order, the only element that has survived until today, installed in the Botanical Garden of Rio de Janeiro. Although he built little of what he designed, Grandjean's architectural classes trained several architects who played an important role in affirming the neoclassical style throughout the Empire period.

Furniture in Colonial Brazil

As Brazil was a Portuguese colony, it is natural that the production of carpentry (with special attention to the furniture pieces) is an offshoot of the traditional Portuguese furniture. Although the material used was legitimately Brazilian, the people responsible for the pieces were always Portuguese, or when born in Brazil of Portuguese or mixed descent. The Portuguese furniture developed in Brazil was simple and unpretentious, that is, only the essentials to perform the function of the object (as examples: small oratories, beds, chairs, tables and arks). The simplicity of the first pieces of the settlers followed as one of the outstanding characteristics of the Brazilian house from that period on.

But, even though these pieces of furniture were simple and unpretentious, they were well crafted, not only because the tradition of the trade was to develop them in this capricious way, but also because the carpentry officers and helpers were often from the house itself (some being slaves whose skills were discovered), who worked without haste and who did not aim for profit, only "the pleasure of doing it well". Brazilian furniture, that is, Portuguese furniture made in Brazil, followed the evolution of furniture in all European countries. The "fashions" were all imported, reaching the wealthier classes first, and were later vulgarized with the production of the same furniture models in the "ordinary" or common type. In the colonial period there were basically three types of furniture: the "luxury" (made with noble hardwood); the "ordinary" (also made with hardwood, but simpler); and finally the "rough" (made with common wood for popular use or domestic services). Furniture in Brazil can be classified into three major periods:

- Renaissance: covers the 16th and 17th centuries and lasts until the early 1970s;

- Baroque-Rococo: extends through practically the entire 18th century;

- Neoclassical: corresponds mainly to the first half of the 19th century, in the historical period of the academic reactions.

After these periods, only fashions originated from the influence of industrial production, which was gradually accentuated.

See also

References

- ↑ "Arqueologia do Forte Duarte Coelho". Brasil Arqueológico (in Portuguese). Retrieved December 17, 2019.

- 1 2 Bazin (1983). A arquitetura religiosa barroca no Brasil.

- ↑ Bueno (2006). A Coroa, a Cruz e a Espada.

- ↑ "Igreja Matriz de Nossa Senhora de Nazaré (Ouro Preto, MG)". Instituto do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional – IPHAN (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on August 6, 2020. Retrieved September 20, 2017.

- 1 2 3 Filho, Nestor Goulart Reis (2019-06-18). "Imagens de vilas e cidades do Brasil Colonial : recursos para a renovação do ensino de História e Geografia do Brasil". Revista Brasileira de Estudos Pedagógicos. 81 (198). doi:10.24109/2176-6681.rbep.81i198.946 (inactive 1 August 2023). ISSN 2176-6681. S2CID 59358551.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of August 2023 (link) - ↑ Silva (2001). A faina, a festa e o rito: uma etnografia histórica sobre as gentes do mar (sécs. XVII ao XIX).

- ↑ Gasparini (1972). Barroco no Brasil: Mais Qualidade que Quantidade.

- ↑ Sant'ana. Período Colonial: outras possibilidades de leitura sobre o planejamento de cidades na América Latina (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-08-23.

- 1 2 Telles (1980). Atlas dos Monumentos Históricos e Artísticos do Brasil.

- ↑ Telles (2005). Francisco Frias da Mesquita, engenheiro-mor do Brasil (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-10-08.

- 1 2 Smith (1948). "Jesuit Buildings in Brazil". The Art Bulletin. 30 (3): 187–213. doi:10.2307/3047183. JSTOR 3047183.

- ↑ Marocci, Gina Veiga Pinheiro (2006). As Aulas de engenharia militar. A construção da profissão docente no Brasil (in Portuguese).

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Colin, Sílvio (2010). Técnicas construtivas do período colonial (I – Vedações e Divisórias; II – Coberturas e forros; III – Esquadrias; IV – Pisos e pavimentos, Pinturas, Alicerces) and Tipos e padrões da arquitetura civil colonial (I; II). Coisas da Arquitetura (in Portuguese).

- ↑ Neves; Faria (2011). Técnicas de construção com terra. pp. 46–50.

- ↑ Bazin (1956). Arquitetura Religiosa Barroca no Brasill.

- 1 2 Vasconcellos (1979). Arquitetura no Brasil: Sistemas Construtivos.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Czajkowski (2001). Guia da Arquitetura Colonial, Neoclássica e Romântica no Rio de Janeiro.

- 1 2 Costa (1941). Arquitetura dos jesuítas no Brasil.

- 1 2 Barbosa (1997). A Igreja e o Colégio de São Miguel da Vila de Santos (1585–1759).

- ↑ Lemos; Leite. Depois de Guararapes.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Telles (1980). Atlas dos Monumentos Históricos e Artísticos do Brasil. p. 75.

- ↑ Telles (1980). Atlas dos Monumentos Históricos e Artísticos do Brasil. p. 76.

- ↑ Neves, André Lemoine (2005). "A arquitetura religiosa barroca em Pernambuco – séculos XVII a XIX". vitruvius (in Portuguese). Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- ↑ Telles (1980). Atlas dos Monumentos Históricos e Artísticos do Brasil. pp. 25–30.

- ↑ "O Conjunto Franciscano". Centro de Estudos Avançados da Conservação Integrada – CECI. Archived from the original on May 31, 2009. Retrieved August 18, 2008.

- ↑ "Arquitetura". Museu de Arte Sacra – MAS/UFBA. Archived from the original on March 27, 2008.

- 1 2 Pereira (1986). Arquitectura Barroca em Portugal.

- ↑ Tirapeli, Percival (2004). "Análise iconográfica da Fachada da Igreja da Ordem Terceira de São Francisco". Tirapeli (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on May 5, 2009.

- ↑ Telles (1980). Atlas dos Monumentos Históricos e Artísticos do Brasil. p. 44.

- ↑ Smith (1956). "Nossa Senhora da Conceicao da Praia and the Joanine Style in Brazil". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 15 (3): 16–23. doi:10.2307/987761. JSTOR 987761.

- ↑ Oliveira (2001). Barroco e rococó na arquitetura religiosa brasileira da segunda metade do século XVIII.

- ↑ Telles (1980). Atlas dos Monumentos Históricos e Artísticos do Brasil. pp. 232–235.

- 1 2 Bury (1955). "The "borrominesque" churches of colonial Brazil". The Art Bulletin. 37 (1): 27–53. doi:10.2307/3047591. JSTOR 3047591.

- ↑ Oliveira (2001). Barroco e rococó na arquitetura religiosa brasileira da segunda metade do século XVIII. pp. 217–218.

- ↑ Oliveira (2001). Barroco e rococó na arquitetura religiosa brasileira da segunda metade do século XVIII. pp. 227–229.

- ↑ Oliveira (2001). Barroco e rococó na arquitetura religiosa brasileira da segunda metade do século XVIII. pp. 230–231.

- ↑ Oliveira (2001). Barroco e rococó na arquitetura religiosa brasileira da segunda metade do século XVIII. pp. 219–220.

- ↑ Miranda (2001). Nos bastidores da arquitetura do ouro: aspectos da produção da arquitetura religiosa no século XVIII em Minas Gerais (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-14.

- 1 2 Oliveira (2001). Barroco e rococó na arquitetura religiosa brasileira da segunda metade do século XVIII. pp. 221–225.

- ↑ Oliveira (2006). O Aleijadinho e o Santuário de Congonhas.

- ↑ "O Forte mais antigo do Brasil". Jornal da Baixada (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on October 1, 2015.

- ↑ Núñez; García (2009). Arquitectura Popular Dominicana. pp. 33–44.

- 1 2 Barreto (1938). "O Piauí e sua arquitetura". Revista do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional (PDF). pp. 187–223.

- 1 2 Zorraquino (2006). A Evolução da Casa no Brasil (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-02-02.

- ↑ Vauthier, Louis Léger (1943). "Casas de Residência no Brasil". Revista do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional (PDF). pp. 128–208.

- ↑ Rolnik (1997). A cidade e a lei: legislação, política urbana e territórios na cidade de São Paulo. Studio Nobel. pp. 26–28. ISBN 978-85-85445-69-0.

- 1 2 Rocha Filho (2005). "Características dos tipos de edificações". Levantamento sistemático destinado a inventariar bens culturais do Estado de São Paulo. pp. 4–7.

- ↑ Espírito Santo (2006). Tipologia da arquitetura residencial urbana em São Luís do Maranhão: um estudo de caso a partir da Teoria Muratoriana.

- 1 2 Gaspar, Lúcia (May 4, 2004). "Palácio de Friburgo, Recife, PE". Fundação Joaquim Nabuco – FUNDAJ (in Portuguese). Retrieved March 23, 2017.

- ↑ Smith (1969). "Arquitetura civil do período colonial". Revista do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional.

- ↑ Telles (1980). Atlas dos Monumentos Históricos e Artísticos do Brasil. pp. 91–93.

- ↑ "Casa do Sertanista". Museu da Cidade de São Paulo – MCSP (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on December 12, 2008. Retrieved August 18, 2008.

- ↑ "Casa do Butantã". Museu da Cidade de São Paulo – MCSP (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on December 11, 2008. Retrieved December 12, 2008.

- ↑ Carvalho (2002). Interiores residenciais recifenses: a cultura francesa na Casa Burguesa do Recife no século XIX (PDF).

- 1 2 3 4 Graham (1956). Diário de uma viagem ao Brasil e de uma estada nesse pais: durante parte dos anos de 1821, 1822 e 1823.

- ↑ Salgado (2006). A presença do neopalladianismo inglês na Praça do Comércio de Salvador (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 2020-07-19.

- ↑ Almeida (2008). Portal da antiga Academia Imperial de Belas Artes: A entrada do Neoclassicismo no Brasil.

Bibliography

- Almeida, Bernardo Domingos de (2008). Portal da antiga Academia Imperial de Belas Artes: A entrada do Neoclassicismo no Brasil. DezenoveVinte. Vol. 3, No. 1 (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro.

- Barbosa, Gino Caldatto (1997). A Igreja e o Colégio de São Miguel da Vila de Santos (1585–1759). Revista de Estudos e Comunicações da Universidade Católica de Santos. Vol. 23, No. 64 (in Portuguese). Santos.

- Barreto, Paulo Tedim (1938). Revista do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional. No. 2 (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: Ministério da Educação e Saúde.

- Bazin, Germain (1983). A arquitetura religiosa barroca no Brasil (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: Record.

- Bueno, Eduardo (2006). A Coroa, a Cruz e a Espada. Coleção Terra Brasilis Vol. 4 (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: Objetiva.

- Bury, John B. (1955). The "borrominesque" churches of colonial Brazil. The Art Bulletin. Vol. 37, No 1. CAA.

- Carvalho, Gisele Melo de (2002). Interiores residenciais recifenses: a cultura francesa na Casa Burguesa do Recife no século XIX (in Portuguese). Recife: UFPE.

- Costa, Lucio (1941). Arquitetura dos jesuítas no Brasil. Revista do Património Histórico e Artístico Nacional. No. 5 (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro.

- Czajkowski, Jorge (2001). Guia da Arquitetura Colonial, Neoclássica e Romântica no Rio de Janeiro (in Portuguese). Casa da Palavra. ISBN 978-85-87220-25-7.

- Espírito Santo, José Marcelo do (2006). Tipologia da arquitetura residencial urbana em São Luís do Maranhão: um estudo de caso a partir da Teoria Muratoriana (in Portuguese). Recife: UFPE.

- Gasparini, Graziano (1972). Barroco no Brasil: Mais Qualidade que Quantidade. América, Barroco y Arquitectura (in Portuguese). Caracas: Ernesto Armitano.

- Graham, Maria (1956). Diário de uma viagem ao Brasil e de uma estada nesse pais: durante parte dos anos de 1821, 1822 e 1823 (in Portuguese). Nacional.

- Lemos, Carlos A. C.; Leite, José Roberto Teixeira. Depois de Guararapes. Arte no Brasil (in Portuguese). São Paulo: Abril Cultural.

- Miranda, Selma Melo (2001). Nos bastidores da arquitetura do ouro: aspectos da produção da arquitetura religiosa no século XVIII em Minas Gerais. Actas de III Congreso Internacional del Barroco Americano (in Portuguese).

- Neves, Célia; Faria, Obede Borges (2011). Técnicas de construção com terra (in Portuguese). São Paulo: Proterra.

- Núñez, Víctor Durán; García, José Brea (2009). Arquitectura Popular Dominicana (in Spanish). Santo Domingo: Popular.

- Oliveira, Myriam Andrade Ribeiro de (2001). Barroco e rococó na arquitetura religiosa brasileira da segunda metade do século XVIII. Revista do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro.

- Oliveira, Myriam Andrade Ribeiro de (2006). O Aleijadinho e o Santuário de Congonhas. Roteiros do Patrimônio (in Portuguese). Monumenta.

- Pereira, José Fernandes (1986). Arquitectura Barroca em Portugal (in Portuguese). Instituto de Cultura e Língua Portuguesa.

- Rocha Filho, Gustavo Neves (2005). Levantamento sistemático destinado a inventariar bens culturais do Estado de São Paulo. Vol. 11 (in Portuguese) (2nd ed.). São Paulo: CONDEPHAAT.

- Rolnik, Raquel (1997). A cidade e a lei: legislação, política urbana e territórios na cidade de São Paulo (in Portuguese). São Paulo: Studio Nobel.

- Salgado, Ivone (2006). A presença do neopalladianismo inglês na Praça do Comércio de Salvador (in Portuguese).

- Sant'ana, Marcel Cláudio. Período Colonial: outras possibilidades de leitura sobre o planejamento de cidades na América Latina. Projeto Itinerâncias Urbanas no Brasil (in Portuguese).

- Smith, Robert Chester (1948). Jesuit Buildings in Brazil. The Art Bulletin. Vol. 30, No. 3 (in Portuguese). CAA.

- Smith, Robert Chester (1956). Nossa Senhora da Conceicao da Praia and the Joanine Style in Brazil. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. Vol. 15, No. 3, Portuguese Empire Issue. University of California.

- Smith, Robert Chester (1969). "Arquitetura civil do período colonial". Revista do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional. Vol. 5, No. 17 (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro.

- Silva, Luiz Geraldo (2001). A faina, a festa e o rito: uma etnografia histórica sobre as gentes do mar (sécs. XVII ao XIX) (in Portuguese). São Paulo: Papirus. ISBN 978-85-308-0635-4.

- Telles, Augusto Carlos da Silva (1980). Atlas dos Monumentos Históricos e Artísticos do Brasil (in Portuguese). MEC.

- Telles, Augusto Carlos da Silva (2005). Francisco Frias da Mesquita, engenheiro-mor do Brasil. Revista da Cultura. Year 5, No. 9 (in Portuguese).

- Vasconcellos, Sylvio (1979). Arquitetura no Brasil: Sistemas Construtivos (in Portuguese). Belo Horizonte: Rona.

- Vauthier, Louis Léger (1943). Revista do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional. No. 7 (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: Ministério da Educação e Saúde.

- Zorraquino, Luis D. (2006). A Evolução da Casa no Brasil (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: UFRJ. ISBN 978-85-85445-69-0.