College literary societies in American higher education are a particular kind of social organization, distinct from literary societies generally, and they were often the precursors of college fraternities and sororities.[1] In the period from the late 18th century to the Civil War, collegiate literary societies were an important part of campus social life. These societies are often called Latin literary societies because they typically have compound Latinate names.

Literary and other activities

Most literary societies' literary activity consisted of formal debates on topical issues of the day, but literary activity could include original essays, poetry, music, etc. As a part of their literary work, many also collected and maintained their own libraries for the use of the society's members. "College societies were the training grounds for men in public affairs in the nineteenth century."[1]

The societies could fulfill this function because they were independent organizations, and entirely student-run activities. "The societies were virtually little republics, with their own laws and a democratically elected student administration."[1]

Topics could include Classical history, religion, ethics, politics, and current events. Controversial topics not covered in the official curriculum were often the most popular. Studies have been done, for example, finding an increasing discussion of slavery at literary society meetings through the 1850s.[2] In addition to debates, in the years before the Civil War, college literary societies sponsored addresses by politicians and other dignitaries. Most frequently those addresses were delivered in conjunction with graduation. Still, there were also literary society addresses at the beginning of the school year and at other important dates, such as July Fourth.[3] The most famous of those addresses is Ralph Waldo Emerson's "The American Scholar." Yet, there were hundreds of others, most of which were less radical than Emerson's address.[4]

Since these organizations are virtually the oldest kind of student organization in America, where they have survived, they are seen as ancient institutions. One author from Georgia acknowledged that fact (by parody) in discussing his own society: "The origin of the Washington Society dates back to the glory days of the Jurassic Period of the Mesozoic Era. It was during this time that great plant-eating dinosaurs roamed the Earth, feeding on lush growths of ferns and palm-like cycads and bennettitaleans. Meanwhile, smaller but vicious carnivores stalked the great herbivores. The oceans were full of fish, squid, and coiled ammonites, plus great ichthyosaurs and the long-necked plesiosaurs. Vertebrates first took to the air, like the mighty pterosaurs and the first true birds. The supercontinent Pangaea began to break up and disperse itself across the Earth's surface, sending a big chunk of land to the very spot where Thomas Jefferson's decomposed old ass lies buried today. And it is on this same chunk of land, a few miles away, that Mr. Jefferson's University sits, home to the Washington Literary Society and Debating Union."[5]

In April 1978, several literary societies held a Congress hosted by the Dialectic and Philanthropic Societies of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina. It was at this gathering that the Association of American Collegiate Literary Societies (AACLS) was established. For the next two decades, AACLS would hold a Congress in the spring to conduct business, and a Rhetor in the autumn where debates, literary exercises, and exchanges of literary magazines took place.

Libraries

Since every college literary society saw itself as complementing the classical curriculum with the knowledge of current events, the societies also had libraries. "At a number of Northern colleges...the society libraries were larger than the college libraries. The society libraries were also high in quality, as shown by their printed catalogs... The rivalry between the two societies at each college extended to their libraries; each tried to have a larger library than the other."[1] Several societies, especially in the South, would build separate buildings for the societies and their libraries.[1] On the austere college campus of two centuries ago, "the only fairly comfortable and attractive places were the rooms of the literary societies. Their members,... raised money for rugs, draperies, and comfortable, even luxurious, furniture."[1]

Societies on campus

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Typically, a college would have two or more competing societies. The campus societies were generally intense competitors. Some examples include The Irving, The Philaletheian, The Adelphi, and The Curtis at Cornell University, Philodemic and Philonomosian Societies at Georgetown University, the American Whig and Cliosophic Societies at Princeton University, Social Friends and United Fraternity at Dartmouth College, the Irving Sothe Philorhetorian and Peithologian societies at Wesleyan University, the Philologian and Philotechnian societies at Williams College, the Philomathean and Zelosophic societies at the University of Pennsylvania, the Philolexian and Peithologian societies at Columbia University, the Clariosophic, Euphradian, and the Euphrosynean societies at the University of South Carolina, the Phi Kappa and Demosthenian societies at the University of Georgia, the Linonia and Brothers in Unity at Yale University, the Miami Union and Erodelphian (previously Adelphic) societies at Miami University and Dialectic and Philanthropic Societies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. These societies were usually in a limited adversarial role; at Columbia University the Peithologian and Philolexian were competitors, and they maintained a friendly and highly charged rivalry at best. In his famous diary, George Templeton Strong recorded that a Philolexian gathering was disrupted by "those rascally Peithologians"; and firecrackers and stink bombs, tossed into the midst of each other's meetings, were usually the weapons of choice.

Membership in these societies was not only open to all the students in the college but in many cases, membership was all but required. At the opening of the University of South Carolina virtually all students were members of the Philomathic Society which was soon divided by lot into the Clariosophic and Euphradian societies. The Euphrosynean Literary Society was later formed at the University of South Carolina to include the female population and serve as a sister society to the Euphradians. In some cases, intense recruitment battles would ensue over new students, and to avoid problems some colleges chose to assign incoming students to one or the other literary society. This pattern was followed, for example, at Dartmouth, where the faculty imposed rule was "The students of College shall be assigned according to the odd or even places which their names shall hold on an alphabetical list of the members of each successive class..."[6] Having two societies on campus encouraged competition, and a thriving society would have interesting enough meetings to attract full attendance from its membership and perhaps even people from the community. These societies met publicly, sometimes in large lecture rooms, and in most instances, the literary exercises would consist of a debate, but could also include speeches, poetry readings, and other literary work.

Private literary societies

There also is a fundamentally distinct type of literary society, that, although formed at a college and following the same forms and kinds of literary exercises, was limited to a small subset of the college. These are private literary societies, such as Phi Beta Kappa or Yale's Elizabethan Club. Membership is usually by invitation. They share all the characteristics of a college literary society, except that they are not open to all students; and they share many of the features of a college fraternity.

Literary societies and fraternities

In the 1830s and 1840s, students began to organize private literary societies for smaller groups, and these more intimate associations quickly developed into wholly secret associations. Groups such as the Kappa Alpha, Sigma Phi, Delta Phi, Mystical Seven, Alpha Delta Phi, Psi Upsilon, and Delta Kappa Epsilon and virtually all the pre-Civil War college fraternities were either first organized as literary societies or derived from factions split off of literary societies. In some cases, literary societies such as Trinity College's Cleo of Alpha Chi became chartered as chapters of national fraternities. These new organizations held meetings and were organized on identical lines to the large literary societies. Soon, the existence of these smaller private Greek letter organizations undermined the large Latin literary societies. Competition from athletics and other entertainments also took a toll, so many dissolved or existed in name only by the 1880s. A literary society almost always provided its members with an extensive library, either available to members only or to the campus at large. When the societies dissolved, their libraries were transferred to the college libraries, and in many colleges the acquisition of the literary societies' libraries was a significant change in their collection, usually broadening the college's libraries' scope into popular literature, but often also adding important and rare works.

Although literary societies had Latin names, and fraternities had Greek names reduced to initials, this is not always the case, however; Phi Phi Society at Kenyon and the Phi Kappa at Georgia are examples of large literary societies with Greek names. The Clariosophic and Euphradian societies at South Carolina both had Greek letter aliases, Mu Sigma Phi and Phi Alpha Epsilon, respectively, which appeared on their seals, but which were not used in normal conversation or writing.

In the following table, there are two types of literary societies listed together, the college literary societies, (frequently half the college's student body), and smaller private societies, and were admitted by invitation. Some of these societies are still active.

Today

The University of Georgia hosts two literary societies (both of which were temporarily disbanded during the Civil War and the subsequent Union occupation): the Demosthenian Literary Society, founded in 1803, and the Phi Kappa Literary Society, founded in 1820 and dormant from the 1970s until its official reestablishment in 1991. Similarly, the Philolexian Society of Columbia University, established in 1802, operated more or less continuously until expiring in the early 1950s and, except for a brief revival in the early 1960s, was not revived until 1985. The Dialectic and Philanthropic Societies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill were founded in 1795, closed for approximately four years when the university was shuttered during Reconstruction and reopened. These societies merged in 1959 and still meet today as a "joint senate." The Euphradian Society at the University of South Carolina, established in 1806, was deactivated sometime during the late 1970s; it was reactivated by alumni in 2011. The Clariosophic Society, also established in 1806 at the University of South Carolina, was reactivated in 2013. The Euphrosynean Literary Society, established in 1924 at the University of South Carolina, was reactivated in 2015. The Linonian Society at Yale University is the oldest society to still be in existence, founded in 1753, the society went sometime in the 1890s and was revamped at the beginning of the 21st century making it with over a century of dormancy the oldest literary society in the United States.

In recent years, the Philodemic Society of Georgetown University has attempted to resuscitate the long tradition of intercollegiate debate between collegiate literary societies with the Annual East Coast Conference of Collegiate Literary Debate Societies, held in conjunction with a masked ball known as the Kai Yai Yai ball. The competition is held at the beginning of October and has in recent years included the Philomathean Society, the American Whig-Cliosophic Society of Princeton University, the Dialectic and Philanthropic Societies of the University of North Carolina, the Demosthenian Literary Society and Phi Kappa Literary Society of The University of Georgia in Athens, the Enosinian Society of The George Washington University and the Jefferson Literary and Debating Society of the University of Virginia.[7]

Some early college social fraternities still meet in a literary society format, including Kappa Alpha, Alpha Delta Phi, and Mystical 7.

There are seven literary societies at Illinois College in Jacksonville, Illinois where they have remained despite the nationwide trend of developing into fraternities and sororities; these include: Phi Alpha Literary Society, Chi Beta Literary Society, Sigma Pi Literary Society, Gamma Nu Literary Society, Sigma Phi Epsilon Literary Society, Pi Pi Rho Literary Society, and Gamma Delta Literary Society.

List of college literary societies

Image gallery

The University of Pennsylvania Philomathean Society Meeting Room circa 1913

The University of Pennsylvania Philomathean Society Meeting Room circa 1913 The Philodemic Society Room in 1910

The Philodemic Society Room in 1910 Philomathean Hall of Erskine College

Philomathean Hall of Erskine College Clio Hall of Princeton University

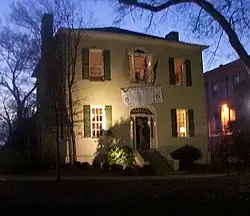

Clio Hall of Princeton University_-_University_of_Georgia%252C_Demosthenian_Hall%252C_Athens%252C_Clarke_County%252C_GA_HABS_GA%252C30-ATH%252C4A-1.tif.jpg.webp) Demosthenian Hall at the University of Georgia

Demosthenian Hall at the University of Georgia The Dialectic Society Chamber in New West at the University of North Carolina

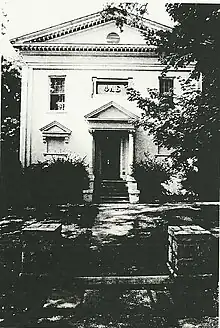

The Dialectic Society Chamber in New West at the University of North Carolina Jefferson Hall at the University of Virginia

Jefferson Hall at the University of Virginia

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Harding, Thomas S. (1971) College Literary Societies: Their Contribution to Higher Education in the United States, 1815-1876. New York: Pageant. ISBN 9780818102028

- ↑ See, e.g., Timothy J. Williams, Intellectual Manhood: University, Individual, Self, and Society in the Antebellum South (2015); Peter S. Carmichael, The Last Generation: Young Virginians in Peace, War, and Reunion (2009); Alfred L. Brophy, "Debating Slavery and Empire in the Washington College Literary Societies," Washington and Lee Journal of Civil Rights and Social Justice 22 (2016): 273 (discussing shifting nature of debates at Washington College's Graham and Washington Societies); Mark Swails, Literary Societies as Institutions of Honor at Evangelical Colleges in Antebellum Georgia (MA thesis, Emory University, 2007).

- ↑ See, e.g., Alfred L. Brophy, "'The Law of the Descent of Thought': Law, History, and Civilization in Antebellum Literary Addresses," Law and Literature 20 (2008): 343-402; Alfred L. Brophy, "The Republics of Liberty and Letters: Progress, Union, and Constitutionalism in Graduation Addresses at the Antebellum University of North Carolina," North Carolina Law Review 89 (2011): 1879.

- ↑ Brophy, Alfred L. "The Rule of Law in Antebellum College Literary Addresses: The Case of William Greene," Cumberland Law Review 31 (2001): 231-85.

- ↑ "The Washington Literary Society and Debating Union - History". Scs.student.virginia.edu. 1979-11-16. Retrieved 2010-09-05.

- ↑ Lord, John King, A History of Dartmouth College, 1815, 1909, (Concord, N. H.: The Rumford Press, 1913), p. 515.

- ↑ Ringwald, Madeleine (2013-10-15). "PHILODEMIC WELCOMES GROUPS FROM UGA, UPENN, AND GWU". philodemicsociety.org. The Philodemic Society. Retrieved 4 February 2015.